January 5, 2016

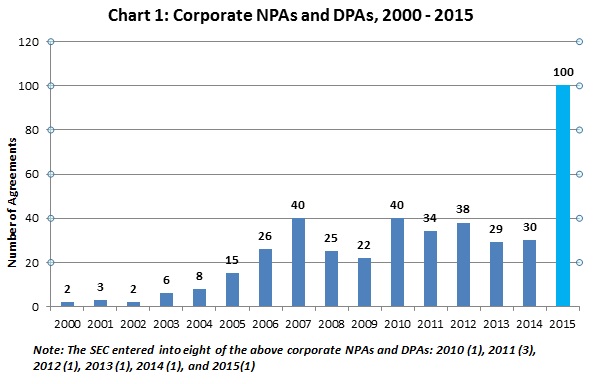

2015 was a blockbuster year in corporate non-prosecution agreements (“NPA”) and deferred prosecution agreements (“DPA”), by sheer numbers alone. Skyrocketing to 100, in 2015 the number of agreements more than doubled the numbers in every prior year since 2000, when Gibson Dunn first began tracking NPA and DPA data. The Department of Justice (“DOJ”) Tax Division’s Program for NPAs or “Non-Target Letters” for Swiss Banks (the “DOJ Tax Swiss Bank Program”) is primarily responsible for this dramatic increase. While DOJ and Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) officials continue to emphasize the heightened cooperation required for corporations to secure an NPA or DPA, these agreements remain critical tools for resolving allegations of corporate misconduct in the United States. They may soon become more utilized tools in the United Kingdom as well; the U.K. Serious Fraud Office (“SFO”) issued its much-anticipated first DPA in December 2015, marking the beginning of a potential trend. This DPA also marked the SFO’s first corporate enforcement action under section 7 of the 2010 Bribery Act. Analysis of these and other developments follows in the pages below.

This client alert, the fifteenth in our series of biannual updates on NPAs and DPAs (available here): (1) summarizes highlights from the NPAs and DPAs of the second half of 2015; (2) evaluates the potential impact of Deputy Attorney General Sally Quillian Yates’s September 9, 2015 memorandum regarding individual liability on corporate NPAs and DPAs; (3) spotlights the importance of corporate compliance programs to obtaining favorable resolution terms; (4) discusses “non-contradiction clauses” and related post-agreement collateral consequences; (5) addresses new developments in judicial scrutiny of these agreements, a topic addressed in our 2015 Mid-Year Update; and (6) analyzes the SFO’s inaugural DPA. As in previous updates in this series, Appendix A to this publication lists all agreements announced in 2015.

NPAs and DPAs in 2015

In 2015, DOJ and the SEC cumulatively entered into an eye-popping 100 corporate NPAs and DPAs, of which 87 were NPAs and 13 were DPAs. Of these, DOJ entered into all but one. The SEC continued to limit its use of NPAs and DPAs, entering into only one agreement–a DPA–in 2015. We anticipate that DOJ’s pattern of outpacing the SEC with respect to the number of NPAs and DPAs will likely continue, for a host of reasons and particularly in light of recent statements by Andrew Ceresney, Director of the SEC’s Division of Enforcement, that in a Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (“FCPA”) case, “a company must self-report misconduct in order to be eligible for the Division to recommend a DPA or NPA to the Commission.”[1] The establishment of bright-line rules such as this, while incentivizing more frequent self-disclosures, also makes attaining an NPA or DPA that much more difficult. Three of the SEC’s eight NPAs and DPAs to date–or 37.5%–and 73 of DOJ’s at least 412 NPAs and DPAs–or 17.7%–have related to the FCPA.

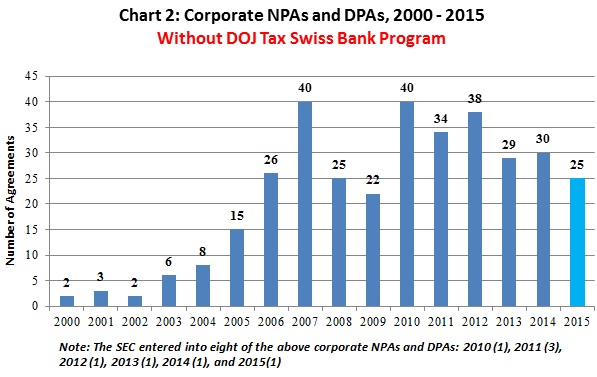

As predicted in our 2015 Mid-Year Update, the substantial majority of the 100 corporate NPAs and DPAs issued this year were associated with the DOJ Tax Swiss Bank Program. Indeed, if we were to remove the 75 agreements associated with that Program, the total number of corporate NPAs and DPAs issued in 2015 would rest at 25, a number that is, in fact, lower than the number of NPAs and DPAs in all years since 2010, and generally consistent with the number of NPAs and DPAs since 2006. Some of the reasons for the relative increase in NPAs and DPAs since 2006–including an increased focus on corporate crime and FCPA enforcement, and the “carrot” of voluntary disclosure–are addressed in our 2010 Year-End Update.

Chart 1 below shows all corporate NPAs and DPAs since 2000.[2]

Chart 2 below shows all corporate NPAs and DPAs since 2000, if the DOJ Tax Swiss Bank Program agreements, the first of which was issued in March 2015, were removed.

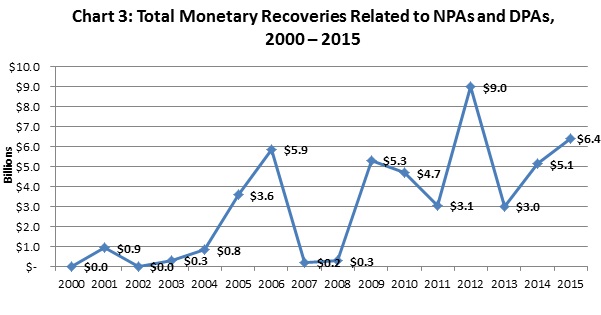

Chart 3 below illustrates the total monetary recoveries related to NPAs and DPAs from 2000 through 2015. At approximately $6.4 billion, 2015’s recoveries show growth over last year’s $5.1 billion, and are substantially higher than 2013’s $2.9 billion. As illustrated in the image below, despite 2015’s unprecedented number of agreements, recoveries this year were not significantly higher than in years past. This consistency is largely attributable to the DOJ Tax Swiss Bank Program, which calculates penalties based predominantly on a bank’s aggregated U.S.-related assets under management that are not compliant with U.S. tax laws. In 2015, 75 Swiss banks entered into agreements under the Program,[3] with an average recovery per bank of approximately $15.3 million and recoveries ranging significantly from $0 to over $200 million. The total amount recovered to date under the DOJ Tax Swiss Bank Program tops $1.14 billion. Of course, these figures do not include a recent announcement by Julius Baer of a $547 million agreement in principle with DOJ to resolve a tax investigation initiated in 2011.[4] Swiss banks that were already under investigation at the time of the DOJ Tax Swiss Bank Program’s release in 2013 were not eligible to participate.[5] Appendix B is a comprehensive list of DOJ Tax Swiss Bank Program agreements in 2015.

The Yates Memorandum: Implications for NPAs and DPAs

DOJ made its most noteworthy policy pronouncement of the year in a September 9, 2015 memorandum issued by Deputy Attorney General Sally Quillian Yates to all United States Attorneys and divisions of DOJ entitled “Individual Accountability for Corporate Wrongdoing” (the “Yates Memorandum”).[6] In it, as described in our September 11, 2015 publication regarding the Yates Memorandum, DOJ stated that companies would receive cooperation credit only if they provided “all relevant facts relating to the individuals responsible for the [corporate] misconduct.”[7] Attending revisions to the U.S. Attorneys’ Manual section regarding the “Principles of Federal Prosecution of Business Organizations” include similar language, noting that if a company fails to disclose “complete factual information about the individuals involved, its cooperation will not be considered a mitigating factor . . . .”[8]

In the four months following the Yates Memorandum, DOJ has issued 44 NPAs and four DPAs. Of these, 43 of 44 NPAs fell within the ambit of the DOJ Tax Swiss Bank Program, which by its basic terms required significant and transparent disclosure of the names and functions of bank employees who served noncompliant “U.S. Related Accounts” as defined by the Program,[9] and factual information about those accounts and how they were serviced.[10] The factual disclosures leading up to the finalization of these agreements were therefore likely consistent with the requirements of the Yates Memorandum. The remaining NPA–relating to Yonkers Contracting Inc.–was not available publicly at the time of this publication, so its consistency with the Yates Memorandum could not be ascertained.[11]

The remaining four DPAs were negotiated by four different U.S. Attorney Offices: those for the District of Columbia, the Eastern District of New York, the Southern District of New York, and the Western District of North Carolina. One of these–the General Motors (“GM”) case discussed below, which followed closely on the heels of the Yates Memorandum–has already been criticized for failing to meet the tenets of the Yates Memorandum because it resulted in no individual action.[12] Similarly, DPAs with Crédit Agricole Corporate and Investment Bank (October 2015) and Tishman Construction Corporation (December 2015) have not involved action against individuals to date.[13] By way of contrast, the Swisher Hygiene case, which culminated in a DPA in October 2015, resulted in a parallel guilty plea by a former senior-level accountant.[14]

In an environment in which DOJ has redoubled its interest in prosecuting individuals, the full impact of the Yates Memorandum remains to be seen. The following sections explore how the Yates Memorandum may affect: (1) the number of NPAs and DPAs that we see negotiated in the coming months, and (2) the ultimate terms of those NPAs and DPAs.

Increase, Decrease, or Status Quo?

Some commentators have suggested that DOJ’s increased focus on individual prosecution in cases involving alleged corporate misconduct may result in an all-or-nothing strategy that foregoes other methods of resolving cases, including NPAs and DPAs, resulting in a concordant decrease in these agreements.[15] Similarly, with the cooperation calculus changed–as we suggested in our September 11, 2015 publication regarding the Yates Memorandum–both corporate entities and individuals may adopt a more defensive posture toward DOJ investigations, and thus limit the use of NPAs and DPAs (as well as other resolution tools) as negotiating options.[16] Deputy Attorney General Yates herself seemed to acknowledge this possibility in a speech accompanying the Yates Memorandum’s release, saying “[l]ess corporate cooperation could mean fewer settlements and potentially smaller overall recoveries by the government.”[17] There is merit to this point, though we note that corporations likely would still be motivated to disclose all relevant facts about rogue employees whom they planned to terminate anyway.

The Yates Memorandum, however, could alternatively be interpreted to require that corporate entities and individual defendants be treated equally, resulting in an increased number of individual NPAs and DPAs as they are negotiated in tandem with their corporate counterparts. A recent judicial opinion, discussed in greater detail below, touches upon the Yates Memorandum and suggests that courts might require the government to offer more individual NPAs and DPAs in cases of corporate wrongdoing.[18]

Finally, Assistant Attorney General for the Criminal Division Leslie Caldwell maintains that the Yates Memorandum simply enshrined longstanding DOJ practices. She noted in a recent interview that the Yates Memorandum is “not really a shift in policy from what the Criminal Division has been doing and also some US attorneys’ offices have been doing in practice. The big change is that it’s now a policy, and something that all federal prosecutors have to do.”[19] If the Yates Memorandum has in fact not introduced a new practice or focus, we could ultimately see no meaningful change in the use of NPAs and DPAs as corporate or individual settlement tools. In our judgment, having negotiated numerous DPAs and NPAs, this interpretation rings true. The Yates Memorandum codifies and reinforces a long-standing trend of focus on individuals.

The Yates Memorandum & Cooperation Credit: From Sliding Scale to Threshold Hurdle

What should we expect from the Yates Memorandum as it relates to the terms of NPAs and DPAs? Although Assistant Attorney General Caldwell has suggested the Yates Memorandum has simply memorialized existing practice, she also has observed that cooperation credit for companies–which had been granted on a “sliding scale”–would now be tied to the provision of facts on potentially culpable individuals.[20] A company that failed to provide “all relevant facts” regarding individuals, despite providing otherwise extensive cooperation, might therefore not receive any credit for that cooperation–at all.[21]

Two and a half months after the Yates Memorandum’s release, Deputy Attorney General Yates offered additional insight. She also adopted the sliding scale metaphor that Assistant Attorney General Caldwell introduced, stating that “[i]n the past, cooperation credit was a sliding scale of sorts and companies could still receive at least some credit for cooperation, even if they failed to fully disclose all facts about individuals. That’s changed now. As the policy makes clear, providing complete information about individuals’ involvement in wrongdoing is a threshold hurdle that must be crossed before we’ll consider any cooperation credit.”[22]

So, even if the Yates Memorandum represents prevailing DOJ orthodoxy, it may be that a company can no longer expect cooperation credit where the company has not provided complete information about individuals involved in misconduct. In such corporate cases, if cooperation credit is truly taken off the table, we might expect to see more draconian terms: a refusal to offer any reduction from Federal Sentencing Guideline minimums, for example, or lengthier agreement terms. This, in turn, could have a chilling effect on voluntary disclosure and corporate cooperation. While enforcement agencies have continued to emphasize the importance of voluntary disclosure–even, in some cases, making it a prerequisite to obtaining a DPA or NPA–creating high fixed hurdles to obtaining fair treatment in exchange for extreme cooperation may diminish the appeal of cooperating at all.[23] Ultimately, the impact of the Yates Memorandum remains to be seen.

Enforcement Agency Emphasis on Corporate Internal Compliance Controls

Recent Enforcement Agency Statements and Appointment of Compliance Counsel

In 2015, DOJ stepped up its rhetoric regarding the critical role of internal compliance departments and officers, and took certain organizational steps that emphasize the value it places on meaningful internal compliance controls.

DOJ and the SEC have stated for years that the presence of internal compliance controls is key to mitigation of potential liability and “may influence whether or not charges should be resolved through a [DPA] or [NPA], as well as the appropriate length of any DPA or NPA . . . .”[24] In early November 2015, Assistant Attorney General Caldwell publicly underscored this point, stating that the “quality and effectiveness of a compliance program is . . . an important factor that prosecutors consider in determining whether to bring charges against a business entity . . . .”[25] As she noted, internal compliance employees are “often the first line of defense” against certain corporate crimes: “[p]rosecutors cannot be everywhere . . . . Well before a grand jury subpoena is served or a witness is interviewed, compliance officers . . . can and do step in and stop issues from becoming problems down the road.”[26]

In assessing the quality and effectiveness of corporate compliance programs, DOJ considers both proactive compliance measures and any “remedial measures . . . compan[ies] took after discovering misconduct . . . .”[27] While acknowledging that a “one size fits all” approach to compliance is inappropriate, DOJ has stated that it generally considers whether compliance programs actively “deter employee misconduct,” beyond simply managing legal risks.[28] A key consideration is whether compliance programs are simply “paper programs” without teeth, or true guides and indicators of compliant corporate culture.[29]

While no enforcement agency has established bright-line, minimum criteria for effective compliance programs, both DOJ and the SEC have articulated many different principles that may contribute to a finding of effectiveness.[30] Features of effective compliance programs that DOJ has most recently emphasized include the following:

- The extent to which the company’s senior leadership “provide[s] strong, explicit and visible support” for the company’s compliance program (i.e., “tone from the top”);

- The extent to which the company grants authority and resources to compliance personnel and programs;

- The extent to which the company’s compliance policies are accessible and comprehensible to employees;

- The frequency and comprehensiveness of internal training programs regarding compliance; and

- Whether the program both rewards compliance and disincentivizes noncompliance–at all levels of the organization.[31]

DOJ also has said that, especially in the context of global financial institutions, it will consider whether a company’s various international offices communicate effectively with each other about potential compliance concerns. In Assistant Attorney General Caldwell’s words, DOJ “expect[s] the left hand to ensure that it knows what the right hand is doing.”[32]

In part to aid in assessing corporate compliance programs, DOJ’s Fraud Section recently hired a dedicated, in-house Compliance Counsel Expert, Hui Chen.[33] Ms. Chen, in the words of Assistant Attorney General Caldwell, “has many years of experience in the private sector assisting global companies in different industries build and strengthen compliance controls.”[34] As a consultant to DOJ, Ms. Chen’s role will include advising prosecutors to “develop appropriate benchmarks for evaluating corporate compliance and remediation measures,”[35] as well as helping steer DOJ’s efforts to monitor corporate compliance pursuant to NPAs and DPAs.[36] She will also be involved in evaluating cases and helping to “test the validity of [a company’s] claims about its [compliance] program, such as whether the compliance program truly is thoughtfully designed and sufficiently resourced to address the company’s compliance risks . . . .”[37] While the precise contours of her role have yet to be defined, one thing is certain: Ms. Chen’s appointment as DOJ’s internal “compliance officer” signals DOJ’s heightened intention to apply both careful scrutiny and thoughtful consideration to companies’ claims about their compliance programs. Thus, companies may expect DOJ to continue to apply a very high bar to securing an NPA or DPA in lieu of prosecution on the basis of existing compliance controls.

There is hope that Ms. Chen’s appointment–and her deep experience shaping and overseeing compliance programs for private entities–will enhance consistency in approach and appreciation for the nuance that attends the evaluation of internal control environments, particularly for large, complex, and multinational organizations. The expectation is that Ms. Chen’s expertise and broad role within DOJ will help harmonize DOJ’s approach to evaluating compliance programs, which must by nature be organization-specific and risk-based.

Collateral Impacts of Non-Contradiction Clauses

A survey of 2014 and 2015 NPAs and DPAs shows that 119 of 130 contain a non-contradiction clause forbidding the company, or individuals speaking on its behalf, to make statements contradicting information in the NPA or DPA. We last discussed the collateral consequences of agreeing to a non-contradiction clause in our 2013 Year-End Update. In 2013, we highlighted how such clauses can limit a company’s post-settlement statements. In the two years since, a non-contradiction clause has been included in nearly every NPA and DPA.[38] As we predicted in our 2013 Year-End Update, the government continues to use the clause to hold companies accountable for their post-agreement statements. In 2013, as discussed in that year’s client alert, Standard Chartered quickly retracted a public statement after DOJ accused the company of violating the non-contradiction clause of its 2012 DPA.[39] In 2015, a similar situation unfolded where GM was forced to withdraw a court filing in response to allegations that it contradicted the statement of facts in a September 2015 DPA with DOJ.[40] As explored below, we expect to see non-contradiction clauses continuing to play a role in settlement term negotiations, with perhaps an increase in third parties leveraging these clauses to advance their interests against organizations that signed an NPA or DPA.

GM’s Non-Contradiction Challenges

GM has come under intense scrutiny, both criminally and civilly, for allegedly knowing it was selling cars with faulty ignition switches. On September 17, 2015, GM entered into a DPA with the government, agreeing to pay $900 million.[41] Many predicted this outcome after Toyota settled its criminal fraud charges for an unprecedented $1.2 billion in 2014.[42] In addition to the DPA resolution, GM has resolved a shareholder class action as well as death and personal injury claims brought by private parties in multidistrict litigation.[43]

On September 29, 2015, GM filed a spoliation motion, claiming that a plaintiff had destroyed his crashed Saturn Ion before crucial information could be extracted from its “sensing diagnostic module” (“SDM”), a device commonly referred to as a “black box.”[44] According to the DPA statement of facts, each “Ion’s SDM was incapable of recording data . . . after the vehicle had lost power” and, therefore, “SDM data recovered from . . . crashed [Saturn Ions] was unilluminating.”[45] Plaintiffs’ counsel, claiming that these statements were contradictory to GM’s motion, alerted the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York in a letter that counsel subsequently shared with the Wall Street Journal.[46]

On October 5, 2015, within hours of learning of the allegation, GM moved to retract its spoliation motion in a court filing, reiterating that it “st[ood] by” the DPA’s statement of facts.[47] A GM spokesman later stated, “We take our commitments under the [settlement] very seriously . . . . [a]fter ensuring consistency with the statement of facts, we intend to refile the motion seeking the same relief.”[48] The U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York declined to comment.[49]

On October 15, 2015, opposing counsel made another allegation in a letter to the U.S. Attorney’s office.[50] The plaintiffs argued that GM had wrongly withheld communication with its own outside counsel, relying on arguments that–the plaintiffs alleged–contradicted the DPA’s statement of facts.[51] GM defended its actions, calling the letter “misleading” because, among other things, it ignored the fact that allegedly contradictory briefs, which advocated for withholding the debated documents, were completed “well before” the DPA.[52] This particular dispute is ongoing.

These recent developments depict a plaintiff’s firm using a company’s non-contradiction obligations as a sword in collateral litigation. Companies should take note of this new precedent and the trends it may foreshadow; GM’s experience signals that non-contradiction clauses can substantially impact collateral litigation, extending to every aspect of proceedings from discovery to the admissibility of evidence, and even reaching the very arguments that a company may permissibly make in its defense.

Non-Contradiction Standards and Variations

Given post-settlement implications, it is important that companies carefully analyze an NPA’s or DPA’s statement of facts and non-contradiction clause before signing the agreement. Frequently, violation of a non-contradiction clause can be cured by retracting the offending statement within a certain period of time, an important protection for any corporate client.[53] The GM clause, for example, and others like it, provide for two business days of notification.[54] Allowing the company to cure a violation is fair and reasonable, though enforcing a two-day window provides a company with little time to cure the defect. DOJ most commonly gives a company five business days to cure a contradictory statement.[55] In the face of a non-contradiction clause, a cure provision is a desirable one and should be sought by companies entering into NPAs or DPAs.

Another approach to non-contradiction taken by DOJ has been to include a “government consultation” provision.[56] In this type of provision, the company is required to consult with the government before issuing a press release or holding any press conference in connection with the agreement.[57] While this tool may allow the government to catch potentially contradictory statements before they go public, it also may be viewed as a significant burden on a company’s speech rights. The GM agreement did not include such a provision.

Although many non-contradiction clauses match the breadth and depth of the one in the GM DPA, others are much more concise. The DOJ Tax Division, for example, authored the same short clause in all of the DOJ Tax Swiss Bank Program agreements in 2015: the bank “admits, accepts, and acknowledges responsibility for the conduct set forth in the Statement of Facts . . . and agrees not to make any public statement contradicting the Statement of Facts.”[58] Because the non-contradiction clause is so short, and because discretion to find breach in each case (as is common in NPAs or DPAs) is reserved exclusively to the government, this clause could in theory provide less room to argue against a finding of breach than would a GM-style clause, which expressly allows for repudiation. While DOJ Tax Swiss Bank Program agreements are fairly cookie-cutter, and the room for banks to negotiate language changes limited, companies outside of the Program should seek a more detailed non-contradiction clause, preserving the organization’s rights to cure, before entering into an NPA or DPA.

Non-contradiction clauses have become a standard element of NPAs and DPAs, and we expect to continue to see their use in the future so long as corporate NPAs and DPAs remain a common settlement vehicle. While non-contradiction clauses have only been implicated in a handful of post-settlement third-party litigation and disputes, companies entering into NPAs or DPAs should be aware of the collateral consequences flowing from enforcement of these clauses. This becomes especially important for larger entities that may have several possible outlets for inadvertently making contradictory statements or statements that appear contradictory, especially litigation that implicates facts related to those at issue in the NPA or DPA.

Judicial Scrutiny – The Trend Continues

Developments in judicial oversight of DPAs, which, unlike NPAs, involve the filing of charges in court, showed no signs of abating in 2015. As first described in our 2013 Mid-Year Update, Judge John Gleeson of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of New York was the first to contemplate an expanded judicial role in 2013 when reviewing the DPA in United States v. HSBC USA, N.A. He noted that the supervisory powers of federal courts over matters on their dockets permitted a limited, yet meaningful, review of the merits of the underlying agreement “to ensure that the courts do not lend a judicial imprimatur to any aspect of a criminal proceeding that smacks of lawlessness or impropriety.”[59] Judge Richard Leon of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, in United States v. Fokker Services B.V., built upon Judge Gleeson’s analysis by using the court’s supervisory powers to reject a DPA between Dutch aerospace services provider Fokker Services and the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Columbia, the first time this had ever been done.[60] Judge Leon’s decision is on appeal.[61]

Drawing on these precedents, Judge Emmett Sullivan of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia recently authored a lengthy opinion approving two DPAs. In doing so, he introduced yet another basis for a more robust judicial review of DPAs; this approach is grounded less in a federal court’s supervisory powers and more in the statutory authority provided by the Speedy Trial Act, which requires judicial approval of DPAs before the duration contemplated by the agreement can be excluded from the seventy-day period in which trial must otherwise commence. Judge Sullivan’s decision adds another, nuanced layer to a small, yet growing body of jurisprudence allowing courts to review the merits of any DPAs placed on their dockets.

Saena Tech / Intelligent Decisions

Judge Sullivan’s Saena Tech decision stemmed from two DPAs revolving around the same alleged bribery scheme. Saena Tech allegedly paid bribes to a U.S. Army contracting officer stationed in South Korea, in exchange for receiving lucrative subcontracts under a prime contract with the Army for providing information technology services.[62] The company later reached a DPA with the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Colombia in April 2014, in which it agreed to pay a fine, implement a compliance program, and cooperate with the government’s ongoing investigation.[63] The agreement also deferred prosecution for Saena Tech’s CEO, Jin Seok Kim, even though Mr. Kim himself had not been charged.[64] Judge Sullivan found Mr. Kim’s involvement in the agreement “somewhat unusual”[65] for two reasons. First, as Judge Sullivan pointed out, Mr. Kim received the benefits of a DPA without having been criminally charged.[66] Second, despite his direct participation in the conduct at issue, Mr. Kim’s treatment stood in stark contrast to others involved in the alleged scheme who had already pled guilty.[67] After briefing and argument on the ability of the court to review the merits of a DPA in August 2014, Judge Sullivan took the matter under advisement.

Another defense contractor, Intelligent Decisions, allegedly bribed the same contracting officer implicated in Saena Tech, in connection with the same prime contract.[68] In October 2014, the government filed a one-count information against Intelligent Decisions for providing a gratuity to a public official, and then filed a motion to exclude time under the Speedy Trial Act and attached DPA.[69] According to Judge Sullivan, the DPA was “rather standard,” requiring the payment of a fine and the implementation of internal controls to prevent the recurrence of the alleged offense.[70] The court requested that Intelligent Decisions review the pleadings filed in Saena Tech regarding the “scope of the court’s authority to accept or reject deferred prosecution agreements,” and ordered briefing on the issue, after which Judge Sullivan took the matter under advisement.

In October 2015, Judge Sullivan issued a comprehensive opinion–relating to both Saena Tech and Intelligent Decisions–addressing the court’s ability to review a DPA pursuant to the Speedy Trial Act as well as its own supervisory powers over matters on its docket. After reviewing both HSBC and Fokker Services, Judge Sullivan delved into the court’s role in DPAs. Under § 3161(h)(2) of the Speedy Trial Act, a court may exclude any “period of delay” from the seventy-day “speedy trial clock,” “during which prosecution is deferred by the attorney for the Government pursuant to written agreement with the defendant, with the approval of the court, for the purpose of allowing the defendant to demonstrate his good conduct.”[71] Judge Sullivan held that the plain language of § 3161(h)(2) requires court approval, yet that does not mean that a court has plenary power to review the agreement.[72] Rather, the clause mandating court approval is “located within the same sentence stating that the agreement must be ‘for the purpose of allowing the defendant to demonstrate his good conduct,'” meaning that the court’s authority is limited to determining whether the agreement satisfies that purpose.[73] According to Judge Sullivan, “[t]his limited authority necessarily involves limited review of the fairness and adequacy of an agreement, to the extent necessary to determine the agreement’s purpose.”[74] Judge Sullivan then sketched out what this review § 3161(h)(2) looked like, suggesting that courts take into account a multitude of factors, such as the reasonableness of fines and the presence of compliance-related safeguards.[75] He cautioned that even an agreement with these elements “could be ineffective if the obligations were found to be so vague and minimal as to render it a sham.”[76]

While rooting his approach primarily in the Speedy Trial Act, Judge Sullivan also noted that the court’s supervisory power over matters on its docket provided an additional, independent source of judicial authority, albeit a much more limited one. Judge Sullivan stressed that the overriding purpose of the supervisory power is to protect the integrity of the court in the administration of criminal justice and prevent it from becoming an accomplice in misconduct.[77] In light of this somewhat limited purpose, he found that the supervisory power can only be employed to reject a DPA when the court’s integrity might truly be imperiled, such as when the agreement imposes “substantial, unrelated obligations on an organization,” like requiring a charitable contribution unrelated to remedying the harm caused by the crime.[78]

Judge Sullivan found that the agreements in Saena Tech and Intelligent Decisions were made pursuant to the purpose contemplated by § 3161(h)(2) and did not implicate the court in any improper conduct.

Judge Sullivan’s opinion, both in its interpretation of the Speedy Trial Act and its analysis of the supervisory power of a federal court, offers yet another approach for federal courts inclined to scrutinize the merits of a DPA, an approach distinct from the arguments used in HSBC and Fokker Services. First, with respect to the Speedy Trial Act, Judge Sullivan interpreted § 3161(h)(2) as allowing an examination of the merits of the underlying agreement for the purpose of concluding whether the DPA allowed the defendant to demonstrate his rehabilitation. This expanded upon Judge Gleeson’s opinion in HSBC, which held that the section “appears to instruct courts to consider whether a deferred prosecution is truly about diversion and not simply a vehicle for fending off a looming trial date”[79]–language that would seemingly limit the inquiry to evaluating the sincerity of the parties’ intentions as opposed to the adequacy of the terms.

Second, Judge Sullivan’s opinion is also distinguishable from Judge Leon’s in Fokker Services, which largely grounded the court’s authority to review DPAs in the supervisory power. While Judge Leon noted in favor of the use of supervisory power that “the integrity of judicial proceedings would be compromised by giving the court’s stamp of approval to either overly-lenient prosecutorial action, or overly zealous prosecutorial action,”[80] Judge Sullivan omitted the leniency and zealousness of prosecutorial action entirely from his discussion.[81] Rather, in Judge Sullivan’s analysis, the leniency of a prosecution would go to whether the agreement is truly about allowing the defendant to demonstrate good conduct under the Speedy Trial Act. While he did not provide an exhaustive list, the circumstances Judge Sullivan identified as necessitating use of the supervisory power appear categorically different from Judge Leon’s in that they suggest a more direct link between court involvement and potential improper action, and do not touch upon an assessment of the leniency or zealousness of individual prosecutorial action.

The Saena Tech Opinion and Individual DPAs

Judge Sullivan’s opinion is not only noteworthy for its new approach to the analysis of a DPA’s adequacy, but also for the considerable attention he gave to the failure of prosecutors to use DPAs with individuals, as opposed to corporations. In his decision, Judge Sullivan traced the history of DPAs and noted that they were originally developed to resolve individual, nonviolent criminal offense cases.[82] He also cited to the Yates Memorandum, discussed above, to highlight the apparent disparity between how DPAs are commonly used with corporate defendants, but very rarely with individual defendants in the same cases.[83]

Judge Sullivan described the Yates Memorandum as a “response to criticism surrounding the practice of failing to prosecute the individuals whose actions are actually the cause of corporate crimes.”[84] However, he then called into question the government’s commitment to pursuing individuals in corporate cases: “Just a week after announcing this policy shift . . . and in a shocking example of potentially culpable individuals not being criminally charged, the Department of Justice announced that it had entered into a Deferred-Prosecution Agreement with General Motors Company (‘GM’) regarding its failure to disclose a safety defect.”[85]

In his opinion, not only does Judge Sullivan imply that the government is too quick to use NPAs and DPAs against corporations when there might be evidence of individual wrongdoing, but he also notes another incongruity: if corporations are allowed to show good behavior during the term of a DPA, per Judge Sullivan, individuals should be allowed to do the same. He writes: “Notwithstanding clear congressional intent . . . the Court is disappointed that deferred-prosecution agreements or other similar tools are not being used to provide the same opportunity to individual defendants to demonstrate their rehabilitation without triggering the devastating collateral consequences of a criminal conviction.”[86] This logic–both that individuals are not being pursued enough, and that DPAs are too infrequently employed with individuals–may lead to more DPAs being used in cases of individual wrongdoing in corporate matters.

Although there surely are instances when allowing an individual to resolve an enforcement action through a DPA makes a great deal of sense, there remain major practical differences between real and juridical persons, some of which may help explain the disparate treatment. As we noted in our 2015 Mid-Year Update, the notion that corporations and individuals can be punished in the same ways in all instances is fundamentally mistaken. When corporations plead guilty or contest the charges against them in trial, the collateral consequences for innocent corporate stakeholders, such as employees, shareholders, and others, are immense. As a result, addressing corporate misconduct requires a range of fine-tuned alternatives, of which DPAs are just one.

The United Kingdom’s Inaugural DPA

On November 30, 2015, the U.K. Crown Court approved the United Kingdom’s first-ever DPA, an agreement between the SFO and Standard Bank Plc (the “Standard Bank DPA”).[87] We recently addressed the Standard Bank DPA, the U.K. DPA regime, and the Standard Bank DPA’s implications for U.K. Bribery Act enforcement in a client alert on December 3, 2015, and our Year-End 2015 FCPA Update. Our 2013 and 2014 Mid-Year and Year-End Non-Prosecution Agreement and Deferred Prosecution Agreement Updates also discuss the history of the United Kingdom’s DPA legislation, effective February 24, 2014, and the Deferred Prosecution Agreement Code of Practice (the “DPA Code of Practice”), a 2014 guidance document published jointly by the SFO and the Crown Prosecution Service, which guides enforcement officials in determining whether DPAs are an appropriate alternative to prosecution. Building upon these publications, in the sections below we (1) briefly overview the reasons for the U.K.’s adoption of a DPA regime; (2) perform a comparative analysis of the Standard Bank DPA to recent DOJ DPAs relating to alleged violations of the FCPA; and (3) consider the implications of the Standard Bank DPA for future U.K. DPAs.

Background on the Introduction and Availability of DPAs in the United Kingdom

DPAs became available enforcement tools for U.K. prosecutors on February 24, 2014, when the SFO and the Crown Prosecution Service finalized the DPA Code of Practice. As noted in our 2013 Mid-Year Update, designated prosecuting agencies (including the SFO) may invite a corporate entity, partnership, or an unincorporated association against which proceedings are contemplated to enter into DPA negotiations. The prosecuting authority has this exclusive right to consider and initiate DPA negotiations.[88]

In contrast to the U.S. DPA regime, DPAs are not available in connection with the prosecutions of individuals. They are also only available for certain offenses, which are primarily economic in nature, including bribery, money laundering, various types of fraud, and certain financial sector crimes. The government introduced DPAs in these limited circumstances as an additional tool to help prosecutors overcome difficulties they faced in successfully prosecuting corporate defendants for economic crimes, or in prosecuting them in an efficient and cost-effective manner.[89]

In particular, because the corporate criminal liability regime in the U.K. makes it difficult to successfully prosecute corporate defendants, a lack of corporate self-reporting frustrated prosecutorial attempts to hold companies accountable for alleged misdeeds. Specifically, under the current law, in order to obtain a conviction, a prosecutor must show that the “directing mind and will” of the commercial organization had the necessary mens rea for the offence (the “Attribution Test”).[90] Satisfying this test usually requires prosecutors to identify a senior corporate executive or board member with the requisite mens rea, and is a particular challenge in an environment where the “directing mind and will” of large commercial organizations are ever more diffuse.[91] The government viewed DPAs as “the next instrument in the battle against economic crime,”[92] in that they would promote self-reporting and cooperation and “allow prosecutors to hold offending organizations to account for their wrongdoing, in a focused way, without the uncertainty, expense, complexity or length of a criminal trial.”[93]

The Standard Bank DPA and its U.S. Counterparts

DPAs have long been used in the United States to resolve allegations of corporate wrongdoing, and the U.K. Ministry of Justice plainly drew upon the U.S. experience and practice in the design and operation of the U.K. regime. While there are a number of similarities between typical U.S. DPAs and the United Kingdom’s inaugural Standard Bank DPA, there are also some noteworthy distinctions, which we analyze in detail below. Although the Standard Bank DPA is the first of its kind and the only U.K. example, it nevertheless–when taken together with the DPA Code of Practice–serves as a harbinger of things to come. The following discussion first provides some factual background regarding the Standard Bank DPA, and then compares the Standard Bank DPA to recent DOJ FCPA DPAs. We focus here on DOJ actions brought pursuant to the FCPA because these most closely approximate prosecutorial actions brought by the SFO pursuant to the U.K. Bribery Act.

Factual Background

The Standard Bank case related to alleged bribery of government officials in Tanzania. In very broad outline, the government of Tanzania wished to raise funds by way of a sovereign note private placement and engaged Stanic Bank Tanzania Ltd (“SBT”)–which in turn engaged Standard Bank–to do so. Both SBT and Standard Bank are subsidiaries of Standard Bank Group Limited.

Negotiations did not progress until SBT agreed to a 2.4% fee to the government of Tanzania, of which 1% would be paid to a local Tanzanian company called Enterprise Growth Market Advisors Limited (“EGMA”). Two of the three directors and shareholders of EGMA were officials of the Tanzanian government, namely, the current Commissioner of the Tanzania Revenue Authority (a member of the Tanzanian government) and the former Chief Executive Officer of the Tanzanian Capital Markets and Securities Authority.

Standard Bank and SBT ultimately raised $600 million, resulting in a $6 million fee to EGMA. The Statement of Facts attached to the DPA indicates that there is no evidence that EGMA provided any services in relation to the transaction. The $6 million fee was subsequently withdrawn in cash from a SBT bank account owned by EGMA at a speed that raised alarms within SBT. Within three weeks of the first report–in April 2013–Standard Bank informed both the Serious and Organised Crime Agency and the SFO of the findings, before it had even commenced its own internal investigation.

As part of a global settlement, Standard Bank also agreed to pay a $4.2 million penalty to settle SEC’s charges under this set of facts under a Cease-and-Desist Order on November 30, 2015,[94] the same date on which Standard Bank’s DPA with the SFO was approved by the Crown Court. For additional details regarding the background to the Standard Bank DPA, including the threshold findings for entering into a DPA and approval and negotiation procedures, please see our December 3, 2015 client alert.

Presentation of Facts

The Standard Bank DPA adopted the common U.S. approach of incorporating a Statement of Facts upon which the DPA’s associated charges are based. These are largely similar in structure: most, for example, detail specifically the conduct at issue, frequently drawing direct quotes from relevant documents; many name and define the roles of implicated high-level employees in allegations while anonymizing the names of other employees and related parties; and all tend to list and define the involved parties and entities as a form of prelude to the detailed factual allegations. There are also, however, two striking differences between typical U.S. DPA Statements of Facts and the Standard Bank Statement of Facts: (1) the SFO, at the outset of the Statement of Facts, sets forth in significant detail the investigative steps taken by the bank and self-disclosed to the SFO; and (2) the SFO quotes extensively from its own investigation’s interviews with Standard Bank and SBT employees, a practice that does not find an analogue in U.S. DPAs. Indeed, U.S. DPAs frequently do not go into the level of detail included in the Standard Bank DPA, and rely more heavily on general descriptions of events.[95]

For example, the Standard Bank DPA Statement of Facts catalogues sources of documents and information collected and analyzed by outside counsel, describes forensic steps taken to evaluate the documents, and contains extensive quotes from SFO-led interviews with key Standard Bank personnel, to whom it frequently refers by name.[96] This is not a practice in the United States.[97] Although interviews are frequently conducted by enforcement agencies in the stages preceding a DPA, statements made in those interviews are not typically quoted; rather, they likely are used as uncited background to support assertions made in Statements of Facts.[98] Investigative details like these both elucidate the level of cooperation required to secure a DPA and support the SFO’s past statements that it would not rely on the internal investigatory steps taken by companies, but rather that “investigation is [the SFO’s] job.”[99]

The difference in the presentation of facts between the U.S. and U.K. may be due in part to the DPA Code of Practice requirements, which indicate that a Statement of Facts must “give particulars relating to each alleged offence” and provide “details where possible of any financial gain or loss.”[100] While there is no further guidance on the level of detail required, the Standard Bank DPA suggests that the DPA Code of Practice has been interpreted–at least in this case–to require a very detailed statement of facts. Companies assessing the prospect of a DPA, or considering an invitation by a U.K. prosecutor to enter into DPA negotiations, will need to be conscious of the level of detail likely to be contained in the published Statement of Facts, and the potential use that may be made of that information by government agencies in other jurisdictions or by affected third parties.

Disclosure of Credible Evidence of Corrupt Payments

U.S. FCPA-related DPAs commonly create a standing requirement to disclose details about newly uncovered evidence of potential corrupt payments. The Weatherford International DPA, for example, requires that the company disclose to DOJ “credible evidence” that (1) “potentially corrupt payments” may have been offered, promised, paid, or authorized by company representatives,[101] and (2) any false books and records have been maintained.[102] Each of the FCPA-related DPAs since 2011 includes some variation of this reporting requirement: should a company uncover evidence of potentially corrupt payments (or even “questionable payments”[103]), it must disclose that evidence to DOJ, potentially leading to additional criminal investigations and unravelling the existing DPA.

Occasionally, the obligation to disclose is even broader, and encompasses disclosure of all potential criminal activity. For example, for Dallas Airmotive, any “credible evidence or allegations of a violation of U.S. federal law” would trigger a reporting requirement.[104] In contrast, the cooperation requirements outlined in the Standard Bank DPA are limited to the four corners of the document: the bank must only cooperate with respect to matters related to the conduct at issue in the Standard Bank DPA Statement of Facts.[105] Nowhere does the Standard Bank DPA require that Standard Bank disclose evidence it has uncovered of unrelated anticorruption matters, providing Standard Bank with greater flexibility when considering disclosure of unrelated conduct.

Cooperation Requirements for Subsidiaries and Affiliates

U.S. DPAs invariably require companies to cooperate fully in any investigations regarding the conduct at issue, frequently including investigations conducted by other agencies or foreign authorities. “Cooperation” in this context usually requires companies to disclose all non-privileged factual information relating to the activities of the company’s parent company, and its subsidiaries or affiliates, along with the activities of its present and former directors, officers, employees, agents, and consultants.[106] Some U.S. DPAs go the extra step of requiring similar or equal cooperation from subsidiaries or affiliates.[107]

As part of its agreement, Standard Bank pledged that it would cooperate “fully and honestly with the SFO and, as directed by the SFO, any other agency” in any matters relating to the conduct at issue.[108] Furthermore, Standard Bank agreed to disclose all non-privileged material in its possession regarding “its activities and those of its present and former directors, employees, agents, consultants, contractors and sub-contractors” relating to the conduct at issue.[109] This language very closely mirrors that of standard U.S. DPAs, making the requirement to disclose information relating to the company’s parent company and affiliates notably absent. As a result, the Standard Bank DPA does not expressly require Standard Bank to disclose information with respect to the actions of its parent or affiliates–a surprising result, given the DPA Statement of Facts’ focus on a sister company of Standard Bank.[110]

The Prosecutors’ Authority

U.S. DPAs uniformly reserve substantial discretion and authority to DOJ to alter, extend, or terminate the terms of DPAs. They generally, for example, give DOJ the ability to extend a DPA “in its sole discretion”–most commonly for a period of one year[111]–should a corporate defendant violate the terms of its DPA, while still preserving the ability to prosecute the corporate defendant for the underlying conduct. This gives DOJ additional time and flexibility to conduct its own investigations, or respond to the results of corporate internal investigations, should a company uncover additional misconduct.

In the Avon Products DPA, for example, DOJ included the following language: “The Company agrees . . . that, in the event the Department determines, in its sole discretion, that the Company has knowingly violated any provision of this Agreement, an extension or extensions of the term of the Agreement may be imposed by the Department, in its sole discretion, for up to a total additional time period of one year, without prejudice to the Department’s right” to prosecute the company.[112] All FCPA-related DPAs from 2012 to the present include substantially similar language to that in Avon Products, allowing DOJ to extend a DPA (and all of its terms) for a fixed period of time, in its sole discretion, without impairing DOJ’s right or ability to prosecute the company or terminate a DPA early.[113] Similarly, U.S. DPAs allow DOJ, “in its sole discretion,” to terminate an agreement or any of its requirements (e.g., a monitorship) early.[114]

The Standard Bank DPA does not include similar language; that agreement only allows for a fixed three-year term (a common term for U.S. DPAs, as well), without expressly leaving room for further unilateral extension.[115]

The omission of a unilateral extension term reduces some risks for corporate defendants, particularly if a company uncovers potential related misconduct during a DPA’s term and discloses those findings to the enforcement agency. Under terms like Standard Bank‘s, absent a finding of breach of the DPA based on the newly disclosed facts, an agency could not extend the DPA for an additional period without the negotiated consent of the corporate defendant. Under U.S. DPA terms, on the other hand, the threat of unilateral extension looms large for many corporate defendants throughout the entire course of a DPA–particularly because of the generally broad disclosure requirements imposed by U.S. DPAs, as discussed above. This is not, of course, to say that without an extension provision a U.K. agency’s leverage would wane completely over the course of a DPA; though it could not unilaterally extend the term, a U.K. agency could always open a new investigation, commence a new prosecution, or weigh past findings and conduct when deciding whether to negotiate a future DPA.

Compliance Program Elements

DPAs in both jurisdictions–the United States and the United Kingdom–impose compliance-related requirements on companies in corruption-related matters. However, the requirements often found in U.S. DPAs describe compliance goals in great detail, usually as a separate Appendix to a DPA, while the Standard Bank DPA includes much less detailed goals. Rather than set forth detailed compliance program requirements, the Standard Bank DPA instead appoints an outside entity–PricewaterhouseCoopers (“PwC”)–to conduct a review of Standard’s Banks policies, procedures, systems, and controls, and produce an independent report with advice and recommendations.[117]

Compliance program requirements in U.S. DPAs vary greatly from case to case, but share several common themes. At a minimum, for example, all FCPA-related DPAs include language requiring the company to represent that it has implemented–and will continue to implement and maintain–a compliance and ethics program designed to prevent and detect violations of the FCPA and other applicable anticorruption laws.[118] U.S. FCPA-related DPAs also typically include an attachment–usually Attachment C–exclusively focused on a company’s compliance program. Attachment C sets forth nineteen focus areas, including–but not limited to–tone‑from‑the‑top (i.e., “high-level commitment” from “directors and senior management” regarding the importance of compliance and anti-corruption),[119] policies and procedures related to anti-corruption, the use of third-party intermediaries, training, employee discipline, internal investigations, and evaluation of anti-corruption issues related to mergers and acquisitions.[120] U.S. DPAs further typically require that the results of a company’s compliance review be periodically reported to the government.

The Standard Bank DPA includes a much less detailed compliance review and remediation program than that commonly seen in U.S. DPAs, instead requiring Standard Bank to hire a third party to perform a review of Standard Bank’s systems and develop tailored recommendations. Specifically, the Standard Bank agreement requires that (1) within one month, Standard Bank commission a report providing advice and recommendations on the use of third-party intermediaries, anti-bribery and anti-corruption training (including monitoring of training completion), and the effectiveness and awareness of those trainings and programs; (2) within three months, Standard Bank must agree on a scope for the report with PwC; (3) within six months of the agreement on scope, PwC must complete the report; and (4) within twelve months of the report’s submission, Standard Bank must implement the report’s advice and recommendations.[121] The high level and general nature of the Standard Bank compliance requirement contrasts sharply with compliance remediation programs typically found in U.S. DPAs; rather than detail specific requirements the company must implement by the end of the DPA’s term, the Standard Bank DPA defers identification of any specific requirements to the judgment and detailed review of PwC.

Also notable is that the Standard Bank compliance review and remediation program must be complete within two years–well before the end of the DPA’s term–with no follow-on reporting requirement. U.S. DPAs, in contrast, typically require mitigation and reporting on compliance matters at least annually for the entire term of the agreement.[122]

Agency Investigation Costs

U.S. DPAs typically contain a provision imposing monetary penalties. The Standard Bank DPA is no different, imposing compensation, disgorgement, and penalties amounting to more than $32.2 million.[123] The Standard Bank DPA also, however, imposes a payment requirement that is unprecedented in U.S. DPAs:[124] Standard Bank must pay “the reasonable costs of the SFO’s investigation and of entering into [the] Agreement in the amount of £330,000.”[125]

While unusual by U.S. standards, the requirement to pay the SFO’s costs is built into the structure of the United Kingdom’s DPA program. Under the DPA legislation, a DPA may (although this is not mandatory) include a term requiring the company to pay the “reasonable costs of the prosecutor in relation to the alleged offence or the DPA.”[126] It continues, “[t]he prosecutor should ordinarily seek to recover these costs, including the costs of the investigation.”[127] The DPA Code of Practice lists this as a term that will “normally” be a term of a DPA.[128]

Non-Contradiction and Clearance of Public Statements

As discussed above, non-contradiction clauses are a common feature of U.S. NPAs and DPAs. Non-contradiction language frequently includes (1) an express agreement not to make “any public statement, in litigation or otherwise, contradicting the acceptance of responsibility by the company . . . or the facts described”;[129] (2) a grant of authority to the relevant prosecuting entity to determine, in its “sole discretion,” whether “any public statement . . . contradicting a fact” constitutes a breach of the agreement;[130] (3) an opportunity for companies to cure apparent breaches in the non-contradiction clauses by “publically repudiating such statements”;[131] and (4) a limitation on the clause, noting that it does not apply to “any statement [made by an individual connected to the company] in the course of any [case] initiated against such individual, unless such individual is speaking on behalf of the company.”[132]

There are variations on this formula, with some agreements also including a requirement to consult with the relevant authority prior to the issuance of a press release or press conference in connection with the agreement.[133] The consultation period allows the authority to determine “(a) whether the text of the release or proposed statements are true and accurate,” and (b) “whether the [relevant authority] has any objection to the release.”[134] Notably, a consultation requirement is fairly common in FCPA cases: in 2014 and 2015, all six FCPA DPAs concluded with DOJ included such a clause.[135]

In contrast, the DPA between Standard Bank and the SFO includes a more limited non-contradiction clause. As do most U.S. DPAs, the agreement provides that Standard Bank shall not make “any public statement contradicting the matters described in the Statement of Facts”[136] and clarifies that the clause does not apply to “statement[s] made by [an individual connected to the company] in the course of criminal or civil proceedings against or by the said individual.”[137] The Standard Bank agreement differs from those in the United States, however, in that (1) it does not give the SFO the sole power to determine whether a statement constitutes a contradictory breach–instead, a claim of contradiction must be adjudicated by the courts;[138] and (2) it does not contain a cure provision, beyond Standard Bank’s fourteen-day written notice provision, which applies in the event of perceived breach by the SFO.[139]

The Standard Bank DPA also does not include the government consultation provision sometimes included in U.S. DPAs, which–as discussed elsewhere in this update–requires consultation with the government prior to issuing public statements relating to the DPA. As this clause has encountered detractors both in the United States and the United Kingdom, its absence may not be surprising. One commentator, for example, referred to such clauses in KPMG’s 2005 DPA and Gibson Guitar’s 2012 NPA as “naked effort[s] by federal prosecutors to control both news and outcomes.”[140] Furthermore, as we reported in our 2013 Year-End Update, in 2010, Lord Justice Thomas in the United Kingdom rejected the idea of government consultation, saying that “[i]t would be inconceivable for a prosecutor to approve a press statement to be made by a person convicted of burglary or rape; companies who are guilty of corruption should be treated no differently to others who commit serious crimes.”

Waivers of Rights

FCPA DPAs with DOJ generally feature a host of waiver requirements. Common terms include waivers of (1) the right to indictment on the charges detailed in the DPA; (2) the right to a speedy trial under the Sixth Amendment and Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 48(b); (3) the right to object to venue; and (4) any defenses based on the statute of limitations.[141] None of these waivers, or their equals, is expressly present in the Standard Bank DPA. Given the applicable regime in the United Kingdom regarding fair trial rights, however, this may not be surprising. Unlike in the United States (as described in other sections above), the United Kingdom does not impose express statutory time limits on trial. The right to a timely trial is recognized in the United Kingdom as part of the right to a fair hearing under Article 6 of the European Convention on Human Rights, and this right is to a hearing “within a reasonable time.”[142] What is reasonable will depend on a number of factors, including the complexity of the case, the behavior of the parties and the length of time between conduct and trial. In circumstances where a party has agreed to enter into a DPA to suspend the prosecution of an offense, it is unlikely that a court would have much sympathy for any argument that a party’s Article 6 rights were breached due to a delay between conduct and hearing, particularly because the party is on notice under the terms of the DPA that it can be prosecuted in circumstances of breach.

DOJ DPAs also often include less express limitations on rights. Recent DPAs, for example, generally require companies to stipulate to the admissibility of an attached Statement of Facts “in any proceeding, including any trial, guilty plea, or sentencing proceeding,” and include an agreement by the company “not [to] contradict anything in the Statement of Facts at any such proceeding.”[143] DOJ FCPA DPAs also commonly include a blanket provision consenting to “any and all disclosures” by DOJ of “information, testimony, documents, records or other materials” provided to DOJ pursuant to the agreement.[144] These disclosures may be made to “other governmental authorities, including U.S. authorities and those of a foreign government,” and the decision to disclose such materials is reserved to the “sole discretion” of DOJ.[145]

These additional limitations on rights, with one exception, are also absent from the Standard Bank DPA. Only the provision stipulating to the admissibility of the Statement of Facts is included: “Standard Bank agrees that it will not contest the admissibility of, nor contradict, the Statement of Facts in any [necessary prosecutorial] proceedings, including a guilty plea and sentencing.”[146] The Standard Bank DPA also expressly states that the Statement of Facts “will be treated as an admission . . . of the facts stated therein” in any subsequent criminal proceedings for the related offense.[147]

Although the Standard Bank DPA does not include a provision consenting to blanket disclosure of materials by the SFO to other agencies, it still requires Standard Bank to “cooperate fully and honestly with the SFO and, as directed by the SFO, any other agency or authority, domestic or foreign, and Multilateral Development Banks, in any and all matters relating to the conduct.”[148] It may be that the SFO believes that a disclosure requirement similar to that specifically imposed by U.S. DPAs is imposed upon Standard Bank through the more general cooperation provision. The SFO may take the view that any direction to Standard Bank to cooperate “fully and honestly” with other authorities would include an inherent direction to disclose all of the same non-privileged material already shared with the SFO.[149] Even if so, however, because the Standard Bank DPA does not give the SFO discretion to determine what disclosures are required, the Standard Bank DPA would appear to reserve greater rights to the company to disclose or withhold information.

Causes for Breach

DPAs in the United States–particularly in the FCPA context–have evolved to include very broad and expansive causes for potential breach. U.S. DPAs today typically reserve sole discretion to DOJ to determine whether breach has occurred.[150] In the FCPA context, they also frequently include the following causes for breach, some of which extend well beyond the conduct at issue in the DPA: (1) commission of any felony under U.S. federal law (even, in some circumstances, any crime);[151] (2) the provision of any deliberately false, incomplete, or misleading information in connection with the agreement;[152] (3) failure to cooperate according to the terms of the agreement;[153] (4) failure to implement a compliance program as set forth in the agreement;[154] (5) failure to retain a compliance monitor, if one is required;[155] (6) commission of any acts that, had they occurred within the jurisdictional reach of the FCPA, would be a violation of the FCPA;[156] and (7) otherwise failing to perform or to fulfill completely each obligation under the Agreement, regardless of whether DOJ becomes aware of such a breach after the term of the agreement is complete.[157] As DOJ is the sole arbiter of breach of a DPA’s terms, this leaves little recourse for a company in the case of disagreement with DOJ’s interpretation of any of the very broad above provisions.

The Standard Bank DPA, in contrast, does not reserve sole discretion to the SFO to evaluate breach, but instead defers to the courts. By its terms, “[i]f, during the Term of this Agreement, the SFO believes that Standard Bank has failed to comply with any of the terms of this Agreement, the SFO may make a breach application to the Court. In the event that the Court terminates the Agreement the SFO may make an application for the lifting of the suspension of indictment associated with the DPA and thereby reinstitute criminal proceedings.”[158]

Further, causes for breach are generally restricted to failure to comply with terms relating to payment (including compensation and costs), cooperation, and Standard Bank’s corporate compliance program. Most notably, the Standard Bank DPA does not include any of the more expansive causes for breach developed by DOJ: absent, for example, are provisions allowing for a finding of breach upon the commission of a crime, or for the commission of an act that would violate the U.K. Bribery Act but for a jurisdictional hook. Indeed, because the Standard Bank DPA does not expressly prohibit further criminal acts, the commission of a criminal act–even a violation of the U.K. Bribery Act–during the term of the agreement would not appear on the face of the DPA to be cause for breach.

The Standard Bank DPA as a Sign of Things to Come

Now that DPAs have formally entered U.K. criminal practice and may be an option for certain corporate defendants, what can we expect the prosecutorial landscape to look like in the United Kingdom? As if to answer this question, U.K. authorities have been careful to stress that DPAs will not be used to the exclusion of other prosecutorial tools. Indeed, the very day after announcement of the Standard Bank DPA, the SFO’s Joint Head of Bribery and Corruption, Ben Morgan, speaking at a conference in London, issued a warning to those who might make that assumption:

[P]lease don’t mistake our willingness to go down this route on this case for a desire to force a DPA onto every corporate case that we take on . . . . In some, quite specific situations they will be appropriate, and we will always have in mind their possible use, but they are not the answer to everything. It is a high bar, for a DPA to be suitable, and where it is not met we have the appetite, stamina and resources to prosecute in the ordinary way.[159]

Interestingly, the SFO had stated in September 2015 that it expected two DPAs to be announced in 2015, but only the Standard Bank DPA has been released as of the date of this publication.[160] It may be that the SFO had initiated DPA proceedings for an entity that it perceived to be an appropriate candidate, only to have the DPA proceedings stall or collapse. On December 2, 2015, for example, the SFO announced that the construction company Sweett Group PLC (“Sweett Group”) had “admitted an offence under Section 7 of the Bribery Act 2010 regarding conduct in the Middle East.”[161] In announcing Sweett Group’s admission, the SFO noted that the matter would “come[] before court,” which may imply that the matter will yet be resolved by DPA.[162] Alternatively, Sweett Group may have been a potential recipient of a second DPA that ultimately never materialized. We will continue to monitor this matter closely.

Certainly, in any event, the SFO appears to be very serious about maintaining its high standards for entering a DPA, with Joint Head of Bribery and Corruption Morgan urging companies to ensure meaningful, proactive and early cooperation:

There is no magic language that can be sprinkled over lawyers’ correspondence that changes our assessment of the substance of the cooperation a company has actually offered. And when it comes to a DPA, that assessment is crucial. We will only invite a company into DPA negotiations if our Director is persuaded that they have offered genuine cooperation.[163]

Lord Justice Leveson’s judgment approving the Standard Bank DPA also provides significant support for the SFO’s approach of insisting on the highest level of cooperation before it will consider a DPA to be appropriate. In his judgment, Lord Justice Leveson noted that Standard Bank’s conduct might not have come to the SFO’s attention had it not been for Standard Bank’s “internal escalation and proactive approach.”[164]

Also clear from the Standard Bank DPA is that the SFO is determined to ensure that DPAs are not seen as a form of “soft option” for corporate wrongdoers. The application of a financial penalty of $16.8 million is among the highest fines imposed in enforcement of the U.K. criminal regime. It is also the largest fine ever imposed for corruption in the United Kingdom. When set alongside the disgorgement, compensation, costs, and cooperation and compliance obligations also imposed on Standard Bank, it is clear that any U.K. DPA will have serious consequences for the defendant organization. Indeed, the overall package of financial obligations (penalty, disgorgement, compensation, and costs) is the second highest ever imposed for corruption in the United Kingdom, trailing only behind the £30.5 million (equivalent to approximately $46 million, today) imposed on BAE in 2010.[165]

APPENDIX A: 2015 Non-Prosecution and Deferred Prosecution Agreements

The chart below summarizes the agreements concluded by DOJ and the SEC during 2015. The complete text of each publicly available agreement is hyperlinked in the chart.

The figures for “Monetary Recoveries” may include amounts not strictly limited to an NPA or a DPA, such as fines, penalties, forfeitures, and restitution requirements imposed by other regulators and enforcement agencies, as well as amounts from related settlement agreements, all of which may be part of a global resolution in connection with the NPA or DPA, paid by the named entity and/or subsidiaries. The term “Monitor” includes traditional compliance monitors, self-reporting arrangements, and other monitorship arrangements found in settlement agreements.

APPENDIX AU.S. Deferred and Non-Prosecution Agreements in 2015 |

||||||

| Company | Agency | Alleged Violation | Type | Monetary Recoveries | Monitor | Term of DPA/NPA |

| Aargauische Kantonalbank | DOJ Tax | Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses | NPA | $1,983,000 | No | 48 months |

| Ansun Biopharma | S.D. Cal. | Fraud (Contract Fraud, Overbilling); False Claims Act | DPA | $2,149,600 | No | 6 months |

| ARVEST Privatbank AG | DOJ Tax | Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses | NPA | $1,044,000 | No | 48 months |

| Banca Credinvest SA | DOJ Tax | Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses | NPA | $3,022,000 | No | 48 months |

| Banca dello Stato del Cantone Ticino | DOJ Tax | Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses | NPA | $3,393,000 | No | 48 months |

| Banca Intermobiliare di Investimenti e Gestioni (Suisse) SA | DOJ Tax | Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses | NPA | $0 | No | 48 months |

| Bank CIC (Schweiz) | DOJ Tax | Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses | NPA | $3,281,000 | No | 48 months |

| Bank Coop AG | DOJ Tax | Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses | NPA | $3,223,000 | No | 48 months |

| Bank EKI Genossenschaft | DOJ Tax | Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses | NPA | $400,000 | No | 48 months |

| Bank J. Safra Sarasin AG | DOJ Tax | Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses | NPA | $85,809,000 | No | 48 months |

| Bank La Roche & Co AG | DOJ Tax | Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses | NPA | $9,296,000 | No | 48 months |

| Bank Linth LBB AG | DOJ Tax | Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses | NPA | $4,150,000 | No | 48 months |

| Bank Lombard Odier & Co Ltd | DOJ Tax | Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses | NPA | $99,809,000 | No | 48 months |

| Bank of Mingo | S.D. WVa. | Bank Secrecy Act | DPA | $2,200,000 | No | 12 months |

| Bank Sparhafen Zurich AG | DOJ Tax | Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses | NPA | $1,810,000 | No | 48 months |

| bank zweiplus ag | DOJ Tax | Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses | NPA | $1,089,000 | No | 48 months |

| Banque Bonhôte & Cie SA | DOJ Tax | Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses | NPA | $624,000 | No | 48 months |

| Banque Cantonale du Jura SA | DOJ Tax | Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses | NPA | $970,000 | No | 48 months |

| Banque Cantonal du Valais | DOJ Tax | Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses | NPA | $2,311,000 | No | 48 months |

| Banque Cantonale Neuchâteloise | DOJ Tax | Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses | NPA | $1,123,000 | No | 48 months |

| Banque Cantonale Vaudoise | DOJ Tax | Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses | NPA | $41,677,000 | No | 48 months |

| Banque Heritage SA | DOJ Tax | Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses | NPA | $3,846,000 | No | 48 months |

| Banque Internationale à Luxembourg (Suisse) SA | DOJ Tax | Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses | NPA | $9,710,000 | No | 48 months |

| Banque Pasche SA | DOJ Tax | Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses | NPA | $7,229,000 | No | 48 months |

| Baumann & Cie, Banquiers | DOJ Tax | Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses | NPA | $7,700,000 | No | 48 months |

| BBVA Suiza S.A. | DOJ Tax | Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses | NPA | $10,390,000 | No | 48 months |

| Berner Kantonalbank AG | DOJ Tax | Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses | NPA | $4,619,000 | No | 48 months |

| BHF-Bank (Schweiz) AG | DOJ Tax | Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses | NPA | $1,768,000 | No | 48 months |

| BNP Paribas (Suisse) SA | DOJ Tax | Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses | NPA | $59,783,000 | No | 48 months |

| Bordier & CIE Switzerland | DOJ Tax | Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses | NPA | $7,827,000 | No | 48 months |

| BSI SA | DOJ Tax | Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses | NPA | $211,000,000 | No | 48 months |

| Coast Produce | C.D. Cal. | False Claims Act | DPA | $4,000,000 | No | 24 months (with possible extension of 12 months) |

| Commerce West Bank | C.D. Cal.: DOJ Consumer Protection | FIRREA | DPA | $4,913,783.20 | No | 24 months |

| Commerzbank A.G. | DOJ AFMLS; S.D.N.Y. | Trade Sanctions/ IEEPA/ Export; Bank Secrecy Act | DPA | $1,452,000,000 | Yes | 36 months |

| Cornèr Banca SA | DOJ Tax | Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses | NPA | $5,068,000 | No | 48 months |

| Coutts & Co Ltd | DOJ Tax | Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses | NPA | $78,484,000 | No | 48 months |

| Crédit Agricole Corporate and Investment Bank | D.D.C. | Trade sanctions/ IEEPA/Export/TWEA | DPA | $312,000,000 | No | 36 months (with possible extension of 12 months) |

| Crédit Agricole (Suisse) SA | DOJ Tax | Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses | NPA | $99,211,000 | No | 48 months |

| Credito Privato Commerciale in liquidazione SA | DOJ Tax | Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses | NPA | $348,900 | No | 48 months |

| Deutsche Bank (Suisse) SA | DOJ Tax | Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses | NPA | $31,026,000 | No | 48 months |

| Deutsche Bank AG | DOJ Fraud; DOJ Antitrust | Fraud (Contract Fraud, Overbilling); False Claims Act | DPA | $2,369,000,000 | Yes | 36 months |

| Digital Reveal LLC | E.D.N.C. | Anti-Gambling Compliance | NPA | $0 | No | 60 months and 56 days |

| Dreyfus Sons & Co Ltd, Banquiers | DOJ Tax | Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses | NPA | $24,161,000 | No | 48 months |

| DZ Privatbank (Schweiz) AG | DOJ Tax | Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses | NPA | $7,452,000 | No | 48 months |

| E. Gutzwiller & Cie, Banquiers | DOJ Tax | Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses | NPA | $1,556,000 | No | 48 months |

| Edmond de Rothschild (Suisse) SA and Edmond de Rothschild (Lugano) SA | DOJ Tax | Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses | NPA | $45,245,000 | No | 48 months |

| EFG Bank European Financial Group SA, Geneva, and EFG Bank AG | DOJ Tax | Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses | NPA | $29,988,000 | No | 48 months |

| Ersparniskasse Schaffhausen AG | DOJ Tax | Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses | NPA | $2,066,000 | No | 48 months |

| Exide Technologiesa | C.D. Cal. | Environmental (RCRA, HMTA, CAA, CWA) | NPA | $133,000,000 | Yes | 120 months |