2021 Mid-Year Securities Litigation Update

Client Alert | August 30, 2021

The torrid pace of new securities class action filings over the last several years slowed a bit in the first half of 2021, a period in which there have been many notable developments in securities law. This mid-year update briefs you on major developments in federal and state securities law through June 2021:

- In Goldman Sachs, the Supreme Court found that lower courts should hear evidence regarding the impact of alleged misstatements on the price of securities to rebut any presumption of classwide reliance at the class-certification stage, and that defendants bear the burden of persuasion on this issue.

- Just before its summer recess, the Supreme Court granted certiorari in Pivotal Software, teeing up a decision on whether the PSLRA’s discovery-stay provision applies to state court actions, which may impact forum selection in private securities actions.

- We explore various developments in Delaware courts, including the relative decline of appraisal litigation, and the Court of Chancery’s (1) decision to enjoin a poison pill, (2) rejection of a claim that the COVID-19 pandemic constituted a material adverse effect, (3) approach in a potential bellwether SPAC case, and (4) analysis of post-close employment opportunities with respect to Revlon fiduciary duties.

- We continue to survey securities-related lawsuits arising in connection with the coronavirus pandemic, including securities class actions, stockholder derivative actions, and SEC enforcement actions.

- We examine developments under Lorenzo regarding disseminator liability and under Omnicare regarding liability for opinion statements.

- Finally, we explain important developments in the federal courts, including (1) the widening circuit split regarding the jurisdictional reach of the Exchange Act based on recent decisions in the First and Second Circuits, (2) the Eighth Circuit’s holding that class action allegations, including those under Section 10(b), can be struck from pleadings, (3) Congress’s codification of the SEC’s disgorgement authority in the National Defense Authorization Act, (4) a federal district court’s holding that a forum selection clause superseded anti-waiver provisions in the Exchange Act, and (5) the Ninth Circuit’s broad interpretation of the PSLRA’s safe harbor for forward-looking statements.

I. Filing and Settlement Trends

According to Cornerstone Research, both the number of new filings and the average approved settlement amount in securities class actions decreased relative to the same period last year and historically. However, the number of approved settlements is the highest it has been since the second half of 2017, indicating that 2021 may be on track to set a record in terms of the number of approved securities class action settlements even if the total dollar amount falls short of last year.

The decline in total filings is driven by a sharp decline in new mergers and acquisitions filings, which are at the lowest level since the second half of 2014. Despite the decline in filings, 2021 has nonetheless already set a record for new SPAC-related filings by doubling both the 2020 and 2019 full-year totals in this category.

A. Filing Trends

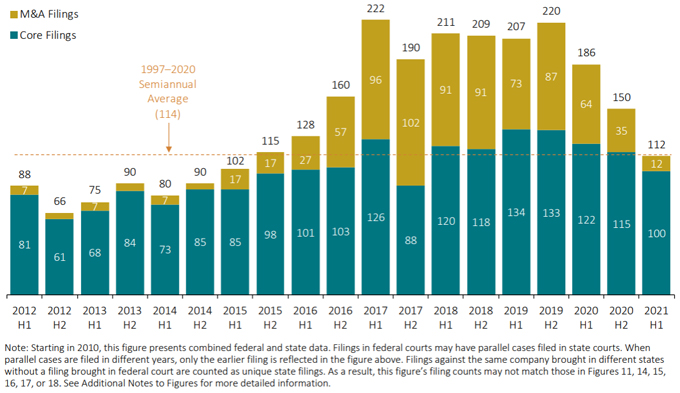

Figure 1 below reflects filing rates for the first half of 2021 (all charts courtesy of Cornerstone Research). The first half of the year saw 112 new class action securities filings, a nearly 40% decrease from the same period last year and a 25% decrease from the second half of 2020. The decrease is largely driven by a drop in new M&A filings, from 64 and 35 in the two halves of 2020, respectively, to 12 in the first half of 2021. This represents a 66% decline in M&A filings from the second half of 2020, and 83% decline against the biannual average for M&A filings dating back through 2016.

Figure 1:

Semiannual Number of Class Action Filings (CAF Index®)

January 2012 – June 2021

B. Industry and Other Trends in Cases Filed

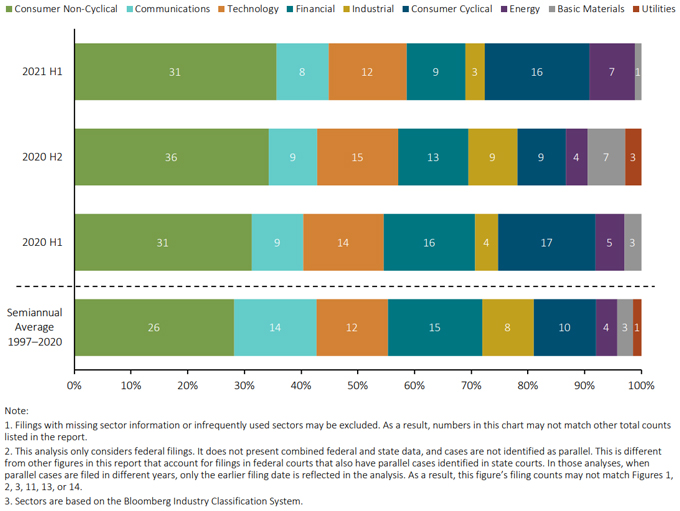

Keeping with recent trends, new filings against consumer non-cyclical firms continued to make up the majority of new federal, non-M&A filings in the first half of 2021, as shown in Figure 2 below. New filings against communications and technology sector firms remained fairly steady, and an increase in filings against firms in the consumer cyclical and energy sectors partially offset the decline in filings against firms in the basic materials, industrial and financial sectors.

Figure 2:

Core Federal Filings by Industry

January 1997 – June 2021

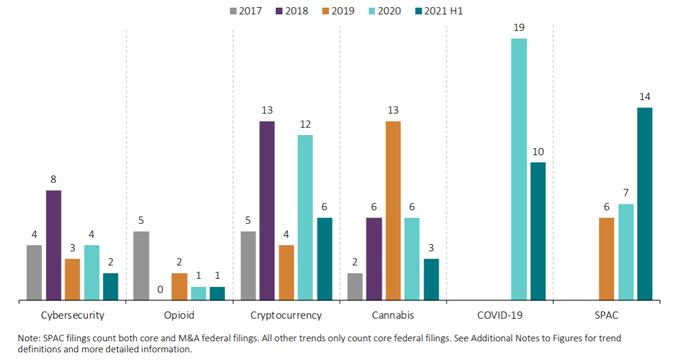

As noted at the start and illustrated in Figure 3 below, the number of SPAC-related filings in the first half of 2021 exceeds those filed in both 2019 and 2020 combined. The increase is driven by filings in the consumer cyclical industry, and specifically, firms in the Auto manufacturers and Auto Parts & Equipment industries. In addition to notable activity in the SPAC space, cybersecurity-, cryptocurrency- and cannabis-related filings are all on pace to meet or exceed the 2020 totals, and 2021’s increased activity in ransomware attacks has already resulted in an uptick in cybersecurity filings in the second half of 2021. On the other hand, the majority of the new filings related to COVID-19 occurred earlier in the year, indicating that, as mentioned below, it is still too early to tell what the full year brings in terms of filings related to COVID-19.

Figure 3:

Summary of Trend Case Filings

January 2017 – June 2021

C. Settlement Trends

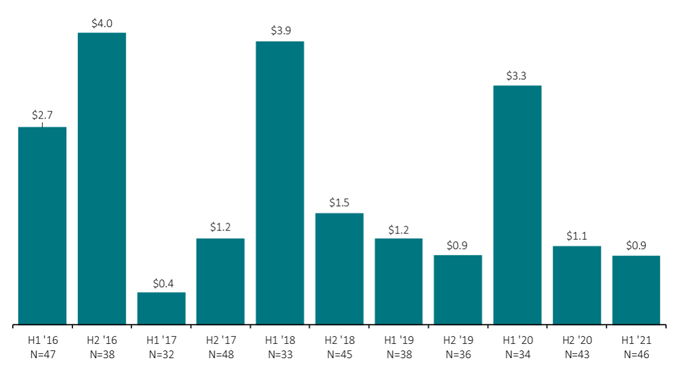

As shown in Figure 4, the total settlement dollars, adjusted for inflation, is down 72.7% against the same period last year despite a 35% increase in the number of settlements approved. Two settlements in the first half of 2021 exceeded $100 million, as compared to six such settlements last year and four in 2019, and the median value of approved settlements through the first half of the year is $7.9 million, reflecting an 18% decline against the same period last year. The difference between the magnitude of the decline in settlement amounts is likely driven by an outlier settlement in first half of last year.

Figure 4:

Total Settlement Dollars (in billions)

January 2016 – June 2021

II. What to Watch for in the Supreme Court

A. Supreme Court Issues Narrow Decision in Price-Impact Case

As we previewed in our 2020 Year-End Securities Litigation Update, in Goldman Sachs Group Inc. v. Arkansas Teacher Retirement System, 141 S. Ct. 1951 (2021), the Supreme Court this Term considered questions regarding price-impact analysis at the class-certification stage in securities class actions. Recall that in Halliburton Co. v. Erica P. John Fund, Inc., 573 U.S. 258 (2014) (“Halliburton II”), the Supreme Court preserved the “fraud-on-the-market” theory that enables courts to presume classwide reliance in Rule 10b-5 cases, but also permitted defendants to rebut that presumption with evidence that the alleged misrepresentation did not affect the issuer’s stock price.

Goldman Sachs presented the Court with the opportunity to decide how courts can address cases in which plaintiffs plead fraud through the “inflation maintenance” price impact theory, which claims that misstatements caused a preexisting inflated price to be maintained instead of causing the artificial inflation in the first instance. In granting certiorari, the Supreme Court accepted two questions for review: (1) “[w]hether a defendant in a securities class action may rebut the presumption of classwide reliance recognized in Basic Inc. v. Levinson, 485 U.S. 224 (1988), by pointing to the generic nature of the alleged misstatements in showing that the statements had no impact on the price of the security, even though that evidence is also relevant to the substantive element of materiality,” and (2) “[w]hether a defendant seeking to rebut the Basic presumption has only a burden of production or also the ultimate burden of persuasion.” Petition for a Writ of Certiorari at I, Goldman Sachs, 141 S. Ct. 1951 (No. 20-222).

In its June 21, 2021 decision, the Court declined to take a position on the “validity or . . . contours” of the inflation-maintenance theory in general, which it has never directly approved. Goldman Sachs, 141 S. Ct. at 1959 n.1. On the first question, the Court unanimously agreed with the parties that lower courts should hear evidence—including expert evidence—and rely on common sense to make determinations at the class-certification stage as to whether the alleged misrepresentations were so generic that they did not distort the price of securities. Id. at 1960. This analysis is permitted at the class-certification stage even though such evidence may also be relevant to the question of materiality, which is reserved for the merits stage. Id. at 1955 (citing Amgen Inc. v. Connecticut Ret. Plans and Tr. Funds, 568 U.S. 455, 462 (2013)). Importantly, the Court noted that in the context of an inflation-maintenance theory, the mismatch between generic misrepresentations and later, specific corrective disclosures will be a key consideration in the price-impact analysis. Goldman Sachs, 141 S. Ct. at 1961. “Under those circumstances, it is less likely that the specific disclosure actually corrected the generic misrepresentation, which means that there is less reason to infer front-end price inflation—that is, price impact—from the back-end price drop.” Id. The Court, with only Justice Sotomayor dissenting, then remanded the case for further consideration of the generic nature of the statements at issue here, explicitly directing the Second Circuit to “take into account all record evidence relevant to price impact, regardless whether that evidence overlaps with materiality or any other merits issue.” Id. (emphasis in original).

As to the second question, the Court held by a 6–3 majority that defendants at the class-certification stage bear the burden of persuasion on the issue of price impact in order to rebut the presumption of reliance—that is, to convince the court, by a preponderance of the evidence, that the challenged statements did not affect the price of securities. The Court determined that this rule had already been established by its previous decisions in Basic and Halliburton II: Basic recognized that defendants could rebut the presumption of classwide reliance by making “[a]ny showing that severs the link between the alleged misrepresentation and . . . the price,” and in Halliburton II, the Court again referenced defendants’ ability to rebut the Basic presumption with a “showing.” Id. at 1962 (internal citations omitted). The majority rejected an argument by the defendants, taken up by Justice Gorsuch (joined by Justices Thomas and Alito), that these references to a “showing” by the defense imposed only a burden of production. Id. at 1962; see also id. at 1965–70 (Gorsuch, J., concurring in part and dissenting in part). That reading would have allowed defendants to rebut the presumption of reliance “by introducing any competent evidence of a lack of price impact”—and would have imposed on plaintiffs the requirement to “directly prov[e] price impact in almost every case,” a requirement that had been rejected in Halliburton II. Id. at 1962–63 (emphasis in original). However, the Court noted that imposing the burden of persuasion on defendants would be unlikely to alter the outcome in most cases, as the “burden of persuasion will have bite only when the court finds the evidence is in equipoise—a situation that should rarely arise.” Id. at 1963.

B. Supreme Court to Decide whether the PSLRA’s Discovery Stay Applies in State Court

On July 2, 2021, just before its summer recess, the Court granted certiorari in Pivotal Software, Inc. v. Tran, No. 20-1541, which raises the question of whether the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act’s (“PSLRA”) discovery-stay provision applies to state court actions in which a private party raises a Securities Act claim. The PSLRA provides that the stay applies “[i]n any private action arising under” the Securities Act before a court has addressed a motion to dismiss, 15 U.S.C. § 77z-1-(b)(1), but state courts are sharply divided over whether the stay applies to suits in state court, rather than only to those in federal court. In opposition, respondent plaintiffs argued that not only is the issue moot (because they have agreed to adhere to the stay provision and the state court will have issued a decision on the motion to dismiss before the Supreme Court can issue an opinion), but also that no court of appeals has ever decided the issue. Brief in Opposition at 7–16, Pivotal Software, Inc. v. Tran, No. 20-1541. Petitioners countered that the issue will only ever arise in state courts and that state trial courts are divided, with at least a dozen decisions refusing to apply the stay and seven applying it, with many more decisions unreported. Moreover, the issue evades appellate review because it is time-sensitive and unlikely to affect a final judgment, rendering any error harmless. Reply Brief for Petitioners at 1–12, Pivotal Software, Inc. v. Tran, No. 20-1541.

Given the costs of discovery in securities actions, Pivotal could have a lasting impact on both the choice of forum in which securities actions are brought and on how discovery progresses in the early stages of a case.

C. The Court Addresses Constitutional Challenges to Administrative Adjudicators

Recall that in Lucia v. SEC, 138 S. Ct. 2044 (2018), the Court held that the SEC’s administrative law judges (“ALJs”) were “Officers of the United States” who must be appointed by the President, a court of law, or the SEC itself. Building on Lucia, the Supreme Court issued two decisions this Term that raised further questions on the constitutionality of administrative officers’ appointments.

Following Lucia, the petitioners in Carr v. Saul and Davis v. Saul sought judicial review of administrative decisions of the Social Security Administration (“SSA”), challenging in the district courts for the first time the constitutionality of SSA ALJ appointments. Carr v. Saul, 141 S. Ct. 1352, 1356–57 (2021). The district courts split on the question of whether petitioners had been required to raise their constitutional challenges during their administrative hearings in the first instance, but both the Eighth and Tenth Circuits agreed that the challenges had been forfeited. Id. at 1357. In its April 22, 2021 decision in these consolidated cases, the Supreme Court unanimously reversed, holding that the petitioners were not required to raise the appointments issue in SSA administrative proceedings, though the Justices were split in their reasoning. Id. at 1356.

The majority opinion held that the benefits claimants were not required to administratively exhaust the appointment issue, in the absence of any statutory or regulatory requirement, for three primary reasons. First, the Court had previously held that the SSA’s Appeals Council conducts proceedings that are more “inquisitorial” than “adversarial,” and that in the absence of “adversarial development of issues by the parties” before the agency tribunal, there was no basis for requiring a petitioner to raise all claims before the agency in order to preserve the issues for judicial review. Id. at 1358–59 (citing Sims v. Apfel, 530 U.S. 103, 112 (2000)). The Court applied the Sims rationale to SSA ALJs who, like the Appeals Council, conduct “informal, nonadversarial proceedings,” even though SSA ALJ proceedings may be considered “relatively more adversarial.” Id. at 1359–60. Second, as the Court has “often observed,” agency decision-makers “are generally ill suited to address structural constitutional challenges, which usually fall outside the adjudicators’ areas of technical expertise.” Id. at 1360. And third, the Court recognized that requiring issue exhaustion here would be futile as the agency adjudicators “are powerless to grant the relief requested.” Id. at 1361. The Court’s consolidated decision in Carr and Davis was dependent on features specific to the SSA’s review, so the question of whether issue exhaustion is required may be answered differently if it arises in future cases, either in the context of an agency with more adversarial administrative review procedures or if the constitutional challenge at issue is “[outside] the context of [the] Appointments Clause.” Id. at 1360 n.5.

In United States v. Arthrex, Inc., 141 S. Ct. 1970 (2021), the Court took up the question of whether administrative patent judges (“APJs”) in the Patent and Trademark Office (“PTO”) are “principal” or “inferior” officers under the Appointments Clause. (Readers should note that Gibson Dunn represented the private parties arguing alongside the government that APJs are inferior officers permissibly appointed by the Secretary of Commerce.) By a 5–4 vote, the majority held that the “unreviewable authority” of APJs to resolve inter partes review proceedings was incompatible with their appointment to an inferior office because “[o]nly an officer properly appointed to a principal office may issue a final decision binding the Executive Branch.” Id. at 1985.

In fashioning a remedy supported by seven Justices, the Court opted for a “tailored approach,” rather than striking down the entire inter partes review regime as unconstitutional. Id. at 1987. Specifically, the Court severed a provision of the statutory scheme that prevented the PTO Director from reviewing APJ decisions. Id. According to the Chief Justice, this remedy would align the Patent Trial and Appeal Board adjudication scheme with others in the Executive Branch and within the PTO itself. Id. In finding that the Constitutional violation is the restraint on the Director’s review authority rather than the APJs’ appointment by the Secretary, the Court found that the proper remedy was remand to the Director rather than to a new panel of APJs for rehearing. Id. at 1987–88.

The majority opinion drew opinions concurring and dissenting in part by Justice Gorsuch (objecting to the Court’s severability analysis) and Justice Breyer (joined by Justices Sotomayor and Kagan, agreeing with Justice Thomas’s analysis on the merits, but supporting the Court’s remedy), as well as a full dissent by Justice Thomas, who criticized the Court’s failure to take a clear position on whether APJs are inferior officers and whether their appointment complies with the Constitution. Id. at 1988–2011. He also disagreed with the Court’s modification of the statutory scheme because, in his view, APJs “are both formally and functionally inferior to the Director and to the Secretary,” and those officers already had sufficient control over APJs. Id. at 2011 (Thomas, J., dissenting).

III. Delaware Developments

A. Court of Chancery Invalidates Poison Pill under Second Unocal Prong

In February, the Court of Chancery in Williams Companies Stockholder Litigation, 2021 WL 754593 (Del. Ch. Feb. 26, 2021), enjoined a stockholder rights plan, also known as a “poison pill.” In March 2020, The Williams Companies, Inc. (“Williams”), a natural gas infrastructure company, adopted a stockholder rights plan after the company’s stock price declined substantially due to fallout from the COVID‑19 pandemic, which decreased demand and lowered prices in the global natural gas markets. Id. at *1. Williams adopted the plan in response to multiple perceived threats, including stockholder activism generally, concerns that activist investors may pursue disruptive, short-term agendas, and the potential for rapid and undetected accumulation of Williams stock (a “lightning strike”) by an opportunistic outside investor. Id. at *2.

The court employed the two-part Unocal standard of review to analyze whether (1) the Williams Board had a reasonable basis to implement a poison pill to respond to a legitimate threat, and (2) the reasonableness of the actual terms of the poison pill in relation to the threat posed. Id. at *22 (citing Unocal Corp. v. Mesa Petroleum Co., 493 A.2d 946 (Del. 1985)). Assuming for the sake of analysis that the “lightning strike” concern constituted a legitimate corporate objective, the court held that the plan’s terms were unreasonable. Id. at *33–34. The plan included a triggering ownership threshold of just 5%, compared to a typical market range of 10% to 15%. Id. at *35–36. It also contained an expansive definition of “beneficial ownership” that covered even synthetic interests, an expansive definition of “acting in concert” that covered any parallel conduct by multiple parties, and a relatively narrow definition of the term “passive investor,” which limited the number of investors exempt from the plan’s provisions. Id. at *35. The court concluded that the combined impact of these terms went well beyond that of comparable rights plans and could impermissibly stifle legitimate stockholder activity. Id. at *35–40. Notably, the court looked beyond the stated rationales listed in board resolutions, board minutes, and company disclosures, and instead sought to determine the actual intent of the directors based on testimony and other evidence. Id. The ruling offers an important reminder that rights plans have limits and that the Court of Chancery will not hesitate to assess a board’s subjective basis for implementing a rights plan and its specific terms.

B. Court of Chancery Rejects Claim that Pandemic Constituted a Materially Adverse Effect

In April, the Court of Chancery in Snow Phipps Group, LLC v. KCake Acquisition, Inc., 2021 WL 1714202 (Del Ch. Apr. 30, 2021), rejected a claim that the COVID‑19 pandemic constituted a material adverse effect (“MAE”) under the agreement at issue. There, a private equity firm buyer signed a $550 million agreement with Snow Phillips to purchase DecoPac, a company that supplies cake decorations and equipment to grocery stores. Id. at *1, *9–10. The deal coincided with the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, which caused a significant decline in DecoPac’s sales. Id. at *1–2. The buyer subsequently attempted to terminate the agreement when it was unable to secure financing based on the target’s revised sales projections. Id. at *24–25.

In the ensuing litigation, the buyer alleged that DecoPac breached a representation that no change or development had, or “would reasonably be expected to have,” an MAE on DecoPac’s finances. Id. at *10. The court rejected this argument, observing—consistent with Delaware precedent—that the existence of an MAE must be judged in terms of DecoPac’s long-term financial prospects (measured in “years rather than months”). Id. at *30. Further, the court noted that the reduction in sales fell within a carve-out from the MAE representation, namely, effects arising from changes in laws or governmental orders. Id. at *35. The decision is notable not just for reaffirming the difficulty of invoking MAE clauses, but also for its broad discussion of how MAE clause carve-outs might negate the occurrence of an existing MAE.

C. Bellwether SPAC Litigation Remains in Initial Stages

In June, the defendants in In re MultiPlan Corp. Stockholders Litigation, Cons. C.A. No. 2021-0300-LWW, filed their motion to dismiss a closely watched consolidated class action filed by the stockholders of MultiPlan, a provider of cost management technology services to insurance agencies. MultiPlan was partially acquired in October 2020 via a reverse merger with a Special Purpose Acquisition Company (“SPAC”), Churchill Capital Corp. III. Most notably, the complaint contends that SPAC structures create inherent conflicts, alleging that MultiPlan’s business prospects have weakened and its stock price has decreased approximately 30% since the acquisition, but the personal investments of individuals managing the SPAC entity have increased materially. The plaintiff stockholders accuse the SPAC, its sponsor, and other directors of issuing misleading and deficient disclosures and of grossly mispricing the transaction.

Although some commentators have characterized the case as a bellwether and the claims asserted as novel, the defendants’ motion to dismiss tracks familiar arguments for attacking complaints concerning merger transactions at the pleading stage. For example, the defendants characterize the claims as derivative and urge dismissal for failure to make a demand. The defendants alternatively assert that, if the claims are direct, they are subject to the business judgment rule and warrant dismissal. More notably, the defendants contend that claims regarding plaintiffs’ redemption rights cannot proceed as fiduciary duty claims because they arise solely from contract. A decision on the pending MultiPlan motion to dismiss may have significant implications for the very active SPAC market, as the Court of Chancery weighs in on the efficacy of these entities and any implications their structure may have for deal disclosures.

D. Court of Chancery Determines CEO Breached Fiduciary Duty and Financial Advisor Aided and Abetted That Breach in Course of Executing a Merger

In Firefighters’ Pension System of the City of Kansas City, Missouri Trust v. Presidio, Inc., 2021 WL 298141 (Del. Ch. Jan. 29, 2021), the Court of Chancery denied motions to dismiss by Presidio’s CEO for allegedly breaching his fiduciary duty and Presidio’s financial advisor for allegedly aiding and abetting that breach, but dismissed claims against the controlling stockholder and other board members. The class action suit challenged a merger of Presidio, a controlled company, with an unaffiliated third party. The court held that a number of actions the CEO allegedly took, if credited, would yield an unreasonable sales process under Revlon. Id. at 267–68. For example, the court credited allegations that the CEO inappropriately steered the bidding process in favor of a private equity buyer that was more eager to retain existing management and simultaneously downplayed to the board of directors the interests of a strategic bidder. Although the strategic bidder allegedly had the capability to pay a higher price as a result of the synergies, it was more likely to replace the CEO. Id. at 267. The court also credited allegations that Presidio’s financial advisor had tipped the potential private equity buyer to confidential information that enabled it to structure its proposed terms into the ultimately bid-winning offer. Id. Presidio has the potential to serve as informative precedent for transactions entailing potential post-close employment opportunities for executives who guide the company’s sale process.

E. Appraisal Litigation Continues Its Steady Decline

The frequency of appraisal litigation continues to decline, with just four appraisal actions filed in the Delaware Court of Chancery in the first half of 2021, compared to the 13 actions filed in the first half of 2020. Going forward, we expect to see appraisal actions concentrated to a subset of deals involving alleged conflicts, process issues, or a limited market check.

Recent appraisal actions that have proceeded continue to reinforce the rulings in DFC Global Corp. v. Muirfield Value Partners, L.P., 172 A.3d 346 (Del. 2017) and Dell, Inc. v. Magnetar Global Event Driven Master Fund Ltd., 177 A.3d 1 (Del. 2017): objective market evidence—including deal price (potentially less synergies) and unaffected market price—generally provides the best indication of a company’s fair value. In In re Appraisal of Regal Entertainment Group, 2021 WL 1916364 (Del. Ch. May 13, 2021), for example, the Court of Chancery awarded a relatively modest 2.6% increase over the original merger price. The court held that the best evidence of the target’s fair value was the deal price, adjusted for post-signing value increases. Id. at *58. The court rejected arguments that Regal’s stock price was the best indicator of fair value, finding that “the sale process that led to the Merger Agreement was sufficiently reliable to make it probable that the deal price establishes a ceiling for the determination of fair value.” Id. at *34.

In the absence of reliable market-based indicators, the Court of Chancery has demonstrated a willingness to fall back on potentially more subjective valuation techniques, including discounted cash flow and comparable company analyses. In January 2021, the Delaware Supreme Court affirmed a Court of Chancery decision awarding a 12% premium on the merger price based solely on a discounted cash flow (“DCF”) valuation. SourceHOV Holdings, Inc. v. Manichaean Capital, LLC, 246 A.3d 139 (Del. 2021). The Court of Chancery’s exclusive use of the petitioner’s DCF valuation was premised on the Respondent’s failure to prove a fair value for the transaction, with the court noting it was “struck by the fact that [Respondent] disagreed with its own valuation expert, relied on witnesses whose credibility was impeached and employed a novel approach to calculate SourceHOV’s equity beta that is not supported by the record evidence. In a word, Respondent’s proffer of fair value is incredible.” Manichaean Capital, LLC v. SourceHOV Holdings, Inc., 2020 WL 496606, at *2 (Del. Ch. Jan. 30, 2020).

IV. Further Development of Disseminator Liability Theory Upheld in Lorenzo

As we initially discussed in our 2019 Mid-Year Securities Litigation Update, in March 2019, the Supreme Court held in Lorenzo v. SEC, 139 S. Ct. 1094 (2019), that those who disseminate false or misleading information to the investing public with the intent to defraud can be liable under Section 17(a)(1) of the Securities Act and Exchange Act, Rules 10b-5(a) and 10b-5(c), even if the disseminator did not “make” the statement within the meaning of Rule 10b-5(b). In practice, Lorenzo creates the possibility that secondary actors—such as financial advisors and lawyers—could face liability under Rules 10b-5(a) and 10b-5(c) (known as the “scheme liability provisions”) simply for disseminating the alleged misstatement of another, if a plaintiff can show that the secondary actor knew the alleged misstatement contained false or misleading information.

In 2021, courts have continued to grapple with Lorenzo’s application, particularly “whether Lorenzo’s language can be read to stretch scheme liability to cases in which plaintiffs are specifically alleging that the defendant did ‘make’ misleading statements (or omissions) as prohibited in Rule 10b5-(b),” or if “Lorenzo merely extends scheme liability to those who ‘disseminate false or misleading statements’ but that it does not hold that ‘misstatements [or omissions] alone are sufficient to trigger scheme liability’” absent additional conduct. Puddu v. 6D Global Techs., Inc., 2021 WL 1198566, at *10 (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 30, 2021) (quoting SEC v. Rio Tinto PLC, 2021 WL 818745, at *2 (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 3, 2021)) (summarizing the divergent views of various district courts).

In June, the Ninth Circuit, in In re Alphabet, Inc. Securities Litigation, 1 F.4th 687 (9th Cir. 2021) (“Alphabet”), signaled its support for the view that disseminator liability does not require “conduct other than misstatements.” Alphabet involved allegations that executives at Google and its holding company, Alphabet, were aware of security vulnerabilities on the Google+ social network. Id. at 693–97. Plaintiffs brought a claim against Alphabet under Rule 10b-5(b), in addition to scheme liability claims under Rule 10b-5(a) and (c), alleging a scheme to defraud shareholders by withholding material and damaging information about the security vulnerabilities from Alphabet’s quarterly filings. See id. at 698. The district court granted Alphabet’s motion to dismiss in full, finding that plaintiffs had failed to adequately allege a misrepresentation or omission of a material fact and failed to adequately allege scienter for the purposes of their Rule 10b-5 claims. Id.

On appeal, the Ninth Circuit reversed in part, holding that that the trial court erred by dismissing the claims under Rule 10b-5(a) and (c) because defendants had not specifically moved to dismiss those claims but instead moved to dismiss only on the basis of Rule 10b-5(b) and Rule 10b-5 generally. Id. at 709. Notably, the panel also disagreed with Alphabet’s “argument that Rule 10b-5(a) and (c) claims cannot overlap with Rule 10b-5(b) statement liability claims” because such an argument “is foreclosed by Lorenzo, which rejected the petitioner’s argument that Rule 10b-5(a) and (c) ‘concern “scheme liability claims” and are violated only when conduct other than misstatements is involved.’” Id. (quoting Lorenzo, 139 S. Ct. at 1101–02).

At the same time, district courts within the Second Circuit are considering the breadth of Lorenzo. See In re Teva Sec. Litig., 2021 WL 1197805, at *5 (D. Conn. Mar. 30, 2021) (summarizing the divergent views). As the Teva court explained, “[s]ome district courts in this circuit apparently agree with the” view that Lorenzo “abrogated the rule that ‘scheme liability depends on conduct that is distinct from an alleged misstatement,’” “[b]ut other district courts cabin Lorenzo and read it more restrictively” to only hold that “‘those who disseminate false or misleading statements to potential investors with the intent to defraud can be liable under [Rule 10b-5(a) and (c)], not that misstatements alone are sufficient to trigger scheme liability.’” Id. (quoting Rio Tinto PLC, 2021 WL 818745, at *2–3).

The Second Circuit itself has not yet squarely addressed the scope of Lorenzo. However, earlier this year, the district court in SEC v. Rio Tinto PLC, 2021 WL 1893165 (S.D.N.Y. May 11, 2021), certified an interlocutory appeal to the Second Circuit, following its dismissal of scheme liability claims where the SEC failed to “allege that Defendants disseminated [the] false information, only that they failed to prevent misleading statements from being disseminated by others.” At the time of this update, the Second Circuit had not ruled on whether it will hear the appeal. Gibson Dunn represents Rio Tinto in this and other litigation.

As these developments suggest, the application of the Lorenzo disseminator liability theory continues to evolve among and within the circuits. We will continue to monitor closely the changing applications of Lorenzo and provide a further update in our 2021 Year-End Securities Litigation Update.

V. Survey of Coronavirus-Related Securities Litigation

Although the stock market has largely stabilized since COVID-19 first impacted the United States in 2020, courts are still feeling the effects of the economic disruption and attendant securities litigation arising out of the pandemic. While the first series of COVID-19 securities lawsuits focused on select industries, such as travel and healthcare, plaintiffs eventually set their sights on other industries. We surveyed a select number of these cases in our 2020 Year-End Securities Litigation Update.

Since then, there have been several dismissals of COVID-19-related securities cases, including dismissals of some of the earliest cases brought in March 2020 concerning the travel industry. Nevertheless, lawsuits for misstatements regarding safety and risk disclosures are still being brought, and now that the “Delta” variant has spread throughout the United States, such lawsuits may continue for the foreseeable future.

Although it is too soon to tell whether the midpoint of COVID-19 securities litigation has passed, we will continue to monitor developments in this area. Additional resources regarding the legal impact of COVID-19 can be found in the Gibson Dunn Coronavirus (COVID-19) Resource Center.

A. Securities Class Actions

1. False Claims Concerning Commitment to Safety

Douglas v. Norwegian Cruise Lines, No. 20-cv-21107, 2021 WL 1378296 (S.D. Fla. Apr. 12, 2021): As we discussed in our 2020 Mid-Year Securities Litigation Update, the COVID-19 pandemic birthed an entire category of class action lawsuits concerning service companies’ commitments to safety, including a proposed class action lawsuit against Norwegian Cruise Lines. In April 2021, Judge Robert Scola, Jr. dismissed the lawsuit, which had originally alleged that Norwegian violated securities laws by minimizing the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on its operations and failing to disclose allegedly deceptive sales practices that downplayed COVID-19. Id. at *2–3. Judge Scola, Jr. concluded that “[a]ll the challenged statements constitute corporate puffery” such that no reasonable investor would have relied on them. Id. at *4.

In re Carnival Corp. Securities Litigation, No. 20-cv-22202, 2021 WL 2583113 (S.D. Fla. May 28, 2021): Similarly, in May 2021, a year after plaintiffs filed the complaint, Judge K. Michael Moore dismissed a putative class action against Carnival that alleged that Carnival misrepresented the effectiveness of its health and safety protocols during the COVID-19 outbreak. Id. at *1–3. The court held that the plaintiffs-investors had failed to show that Carnival’s “statements affirming compliance with then-existing regulatory requirements [were] materially false or misleading” because the plaintiffs’ argument relied on the inference that “passengers would ultimately fall ill aboard Carnival’s ships—just as people did in other venues across the globe.” Id. at *15. Accordingly, the court found the inference was “too tenuous to meet the heightened pleading standard applicable in the securities fraud context.” Id.

2. Failure to Disclose Specific Risks

Plymouth Cnty. Retirement Assoc. v. Array Techs., Inc., No. 21-cv-04390 (S.D.N.Y. May 14, 2021): Plaintiffs allege that Array, a solar panel manufacturer, along with several of its directors and underwriters, failed to disclose that “unprecedented” increases in steel and shipping costs negatively impacted the company’s quarterly results until the company’s CFO revealed the results in a conference call. Dkt. No. 1 at ¶¶ 10–42, 113–15. Upon the release of this news, Array’s stock price fell by $11.49 to close at $13.46. Id. at ¶ 118. Array had previously issued warnings on the “global shipping constraints due to COVID-19” but allegedly failed to disclose the impact of dramatically increasing supply prices and increasing freight costs. Id. at ¶¶ 103, 112. This case was later consolidated with Keippel v. Array Technologies, Inc., 21-cv-5658 (S.D.N.Y. June 30, 2021). Dkt. No. 61 at 1. The case remains pending.

Denny v. Canaan Inc., No. 21-cv-03299 (S.D.N.Y. Apr. 15, 2021): A shareholder of Canaan, a company that manufactures and sells Bitcoin mining machines, alleged that the company misleadingly issued positive statements about strong demand for bitcoin mining machines without disclosing how “ongoing supply chain disruptions” and the introduction of its latest machines had “cannibalized sales of [its] older product offerings,” which caused sales to decline. Dkt No. 1 at ¶ 4. Purportedly, Canaan did not reveal these issues until a conference call to discuss fourth quarter earnings, after which Canaan’s American Depository Receipts, which are a type of securities, declined by nearly 30%. Id. at ¶¶ 27–28.

3. Alleged Insider Trading and “Pump and Dump” Schemes

Tang v. Eastman Kodak Co., No. 20-cv-10462 (D.N.J. Aug. 13, 2020): In our 2020 Year-End Securities Litigation Update, we previously discussed this putative class action, in which stockholders contended Eastman Kodak violated securities law by failing to disclose that its officers were granted stock options prior to the company’s public announcement that it had received a loan to produce drugs for the treatment of COVID-19. Dkt. No. 1 at 2. On May 28, the New Jersey federal judge transferred the case to the Western District of New York, where the alleged misconduct occurred. Dkt. No. 62 at 1. In parallel, New York Attorney General Leticia James commenced an action under Section 34 of General Business Law to seek evidence of insider trading from Kodak. NYSCEF No. 451652/2021, Dkt. No. 1 at 1. On June 15, the court ordered Kodak’s executives to publicly testify. Dkt. No. 9 at 2.

B. Stockholder Derivative Actions

1. Disclosure Liability

Berndt v. Kelly, No. 21-cv-50422 (W.D. Wash. June 4, 2021): In this derivative suit, plaintiff alleges that CytoDyn Inc., which is developing a drug with potential benefits for HIV patients, misleadingly touted the drug as a potential COVID-19 treatment, resulting in a significant increase in the company’s stock price. Dkt. No. 1 at ¶¶ 2–4. “[W]hile the [c]ompany’s stock price was sufficiently inflated with the COVID-19 cure hype,” the complaint alleges, a close circle of long-term shareholders “dumped millions of shares.” Id. at ¶ 6. Following the alleged cash-out of company shares, the price of CytoDyn “dropped precipitously” after it was revealed that the COVID-19 treatment was not commercially viable. Id. at ¶ 8. The suit includes claims for breach of fiduciary duty, waste of corporate assets, unjust enrichment, and violations of the Exchange Act. Id. at ¶¶ 78–98.

Golubinski v. Douglas, No. 2021-0172 (Del. Ch. Apr. 20, 2021): An investor of Novavax Inc. derivatively sued the company’s directors and certain officers, claiming that they granted themselves a series of lucrative equity awards in 2020 with the knowledge that Novavax’s stock was going to increase nearly 700% based on promising COVID-19 vaccine news. Dkt. 1 at ¶¶ 5–13. The investor alleges that “management exploited its relationships with regulators and influential players in the vaccine community to both secure funding and position itself to receive even more funding for COVID-19 research prior to granting spring-loaded awards to [c]ompany insiders.” Id. at ¶ 15. The stock granted to executives in April and June 2020 allegedly rose in value within a few months, after the news became public that the company would be getting billions in funding through Operation Warp Speed, the U.S. government’s COVID-19 vaccine initiative. Id. at ¶¶ 9–13. The derivative suit seeks, among other things, to have the stock awards rescinded. Id. at ¶ 16.

2. Oversight Liability

Bhandari v. Carty, No. 2021-0090 (Del. Ch. Feb. 5, 2021): Two stockholders of YRC Worldwide, Inc. sued the company’s directors, claiming that they oversaw a fraudulent scheme to overcharge customers for freight cargo, and then sought a $700 million government bailout purportedly justified by fraudulent concerns relating to COVID-19. Dkt. 1 at ¶¶ 3–15. The bailout, which plaintiffs allege “made the company one of the largest recipients of taxpayer money meant to support businesses and workers struggling amid the coronavirus,” has now “come under scrutiny from” Congress, which is investigating whether it “was really worthy of a rescue,” according to the complaint. Id. at ¶ 15. Plaintiffs allege that the board “could and should have quickly and responsibly taken action to correct management’s wrongdoing,” but failed to do so. Id. at ¶ 5.

3. Insider Trading

Lincolnshire Police Pension Fund v. Kramer, No. 21-cv-01595 (D. Md. June 29, 2021): Plaintiff sued directors of Emergent BioSolutions Inc. derivatively for claims that the board members allegedly sold a combined $20 million of personally held Emergent shares “on the basis of the nonpublic information about the problems at the Bayview Facility,” where the company was working on a COVID-19 vaccine for Johnson and Johnson. Dkt. 1 at ¶¶ 9, 15–26, 89, 101. The fund claims that the directors allegedly “used their knowledge of Emergent’s material, nonpublic information to sell their personal holdings while the Company’s stock was artificially inflated.” Id. at ¶ 89. Specifically, the allegations are that the directors were supposedly aware of Bayview’s history of internal control failures and inability to handle the “massive and critical work required to manufacture [the COVID-19] vaccines.” Id. at ¶ 3.

In Delaware, another Emergent stockholder brought a Section 220 action against Emergent to enforce his statutory right to inspect the company’s books and records. See Elton v. Emergent BioSolutions, Inc., No. 2021-0426 (Del. Ch. May 21, 2021). There, too, the stockholder alleged that there was a “credible basis to infer the Company’s fiduciaries sold Company stock while in possession of material, non-public information” relating to Emergent’s alleged “regulatory, compliance, and manufacturing failures.” Dkt. 1 at ¶ 3.

C. SEC Cases

SEC v. Arrayit Corp., No. 21-cv-01053 (N.D. Cal. Feb. 11, 2021): As we discussed in our 2020 Year-End Securities Litigation Update, the SEC charged Mark Schena, the President of Arrayit Corporation, a healthcare technology company, for “making false and misleading statements about the status of Arrayit’s delinquent financial reports.” SEC v. Schena, No. 20-cv-06717 (N.D. Cal. Sept. 25, 2020), Dkt. No. 1 at ¶ 1. That case was stayed, pending the resolution of a criminal case against Mr. Schena. Dkt. 23. Since then, the SEC has brought a separate case against Arrayit itself, as well as Mark Schena’s wife, who served as Arrayit’s CEO, CFO, and chairman for over a decade. No. 5:21-cv-01053, Dkt. No. 1 at ¶¶ 1, 11. The new claims brought under Sections 10(b) and 13(a) mirror those in the prior action against Mr. Schena, namely that the defendants allegedly misrepresented the company’s capability to develop COVID-19 tests. Id. at ¶ 1. The parties settled on a neither-admit-nor-deny basis, with Ms. Schena also agreeing to a $50,000 penalty. Dkt. No. 11 at 1–3; Dkt No. 12 at 2.

SEC v. Parallax Health Sciences, Inc., No. 21-cv-05812 (S.D.N.Y. July 7, 2021): This enforcement action, brought under Section 17(a)(1)(3) of the Securities Act and Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act, resulted from a series of seven press releases issued by Parallax, a healthcare company, about its ability to capitalize on the COVID-19 pandemic. Dkt. No. 1 at ¶¶ 1, 4. The SEC’s complaint alleges that Parallax falsely claimed that its COVID-19 screening test would be “available soon” despite the company’s insolvency and the company’s own internal projections showing that, even if it had the funds, other factors prevented the company from acquiring the needed equipment. Id. at ¶¶ 1–2. Parallax, its CEO, and CTO settled with the SEC on a neither-admit-nor-deny basis, and agreed to penalties of $100,000, $45,000, and $40,000, respectively. Dkt. No. 4 at 1, 4.

SEC v. Wellness Matrix Grp., Inc., No. 21-cv-1031 (C.D. Cal. June 11, 2021): The SEC charged Wellness Matrix, a wellness company, and its controlling shareholder for allegedly misleading investors about the availability and approval status of its at-home COVID-19 testing kits and disinfectants in violation of Section 10(b) and Rule 10b-5. Dkt. No. 1 at ¶¶ 6–7, 9. The SEC alleges that the company’s claims were false and, to the contrary, defendants knew its distributor was unable to fulfill the order and the products were neither FDA- nor EPA-approved. Id. at ¶¶ 44–48. The SEC had suspended trading in Wellness Matrix’s securities approximately two months before bringing the action. Id. at ¶ 68.

VI. Falsity of Opinions – Omnicare Update

As we discussed in our prior securities litigation updates, lower courts continue to examine the standard for imposing liability based on a false opinion as set forth by the Supreme Court in Omnicare, Inc. v. Laborers District Council Construction Industry Pension Fund, 575 U.S. 175 (2015). In Omnicare, the Supreme Court held that “a sincere statement of pure opinion is not an ‘untrue statement of material fact,’ regardless whether an investor can ultimately prove the belief wrong,” but that an opinion statement can form the basis for liability in three different situations: (1) the speaker did not actually hold the belief professed; (2) the opinion contained embedded statements of untrue facts; or (3) the speaker omitted information whose omission made the statement misleading to a reasonable investor. Id. at 184–89.

In 2021, federal courts have continued to grapple with whether Omnicare—which was decided in the context of a Section 11 claim—applies to claims brought under the Exchange Act. In April, the Ninth Circuit extended the Omnicare standard to claims brought under Exchange Act Section 14(a) and Rule 14a-9. Golub v. Gigamon Inc., 994 F.3d 1102, 1107 (9th Cir. 2021). The court reasoned that such claims contain a “virtually identical limitation on liability” to claims under Section 11 and Rule 10b-5, to which the Ninth Circuit held Omnicare applies. Id.; see also City of Dearborn Heights Act 345 Police & Fire Ret. Sys. v. Align Tech., Inc., 856 F.3d 605 (9th Cir. 2017).

Two additional cases addressing Omnicare’s application to the Exchange Act came down in the District of New Jersey, with one of them ultimately deciding to apply the Omnicare standard for falsity to claims brought under Section 10(b) and Rule 10b-5. Ortiz v. Canopy Growth Corp., No. 2:19-cv-20543, 2021 WL 1967714 (D.N.J. May 17, 2021). Recognizing the majority view outside the Third Circuit that Omnicare applies to such claims, the court in Ortiz “s[aw] no reason to apply a different rule.” Id. at *33. However, after finding that the alleged statements were actionable under Omnicare, the court still dismissed the complaint for failure to plead scienter. Id. at *44. While plaintiffs adequately pled that defendants did not believe certain statements when they were made and misleadingly omitted certain material facts, plaintiffs could not overcome the PLSRA’s high bar for scienter. Id. at *38–39. The court found that plaintiffs failed to plead facts to support a “strong inference” of scienter because, based on several factors, another more “innocent explanation” was plausible. Id. at *42–43. In another case, a District of New Jersey court found evaluation of Omnicare unnecessary for the same reason: Plaintiffs did not plead facts to “support a ‘strong inference’ of scienter.” In re Amarin Corp. PLC Sec. Litig., No. 3:19-cv-06601, 2021 WL 1171669 at *19 (D.N.J. Mar. 29, 2021). These cases suggest Omnicare may rarely be outcome-determinative for Section 10(b) and Rule 10b-5 claims because opinions that may be actionable under Omnicare may often lack an “intent to deceive, manipulate, or defraud,” as required to demonstrate scienter. See Ortiz, 2021 WL 1967714, at *10.

Omnicare has remained a significant pleading barrier in the first half of 2021. In Salim v. Mobile Telesystems PJSC, No. 19-cv-1589, 2021 WL 796088 (E.D.N.Y. Mar. 1, 2021), the Eastern District of New York held that a statement about potential liability resulting from investigations into alleged FCPA violations “would have necessarily been a statement of opinion until the company could give a reasonable estimate of its potential losses.” Because plaintiff failed to allege sufficient facts to show that defendant did not actually believe what it stated, the court granted defendants’ motion to dismiss. Id. at *8–9. Similarly, in City of Miami Fire Fighters’ and Police Officers’ Retirement Trust v. CVS Health Corp., the District of Rhode Island held that reported results of goodwill assessments conducted under Generally Accepted Accounting Principles are opinion statements that must be assessed under Omnicare because “[e]stimates of goodwill depend on management’s determination of the fair value of the assets acquired and liabilities assumed, which are not matters of objective fact.” No. 19-437-MSM-PAS, 2021 WL 515121, at *9 (D.R.I. Feb. 11, 2021). In granting defendants’ motion to dismiss, the court found allegations “amount[ing] to a retrospective disagreement with [defendant’s] judgment” inadequate “without sufficient facts to undermine the assumptions [defendant] used when it made its goodwill assessments.” Id. at *10.

Other recent district court decisions illustrate the narrow situations in which plaintiffs have overcome Omnicare’s high bar. For instance, in Howard v. Arconic Inc., defendants argued that aluminum manufacturer Arconic’s statement that it “believes it has adopted appropriate risk management and compliance programs to address and reduce” certain risks was a non-actionable opinion under Omnicare. No. 2:17-cv-1057, 2021 WL 2561895, at *7 (W.D. Pa. June 23, 2021). The court disagreed, holding that the statement “conveyed to investors that there was a reasonable basis for [defendants’] belief about the adequacy of the compliance/risk management programs,” but facts regarding Arconic’s practice of selling hazardous products “call[ed] into question the reasonableness of that belief.” Id.

Finally, in SEC v. Bluepoint Investment Counsel, LLC, the SEC claimed that the investment-advisor defendants had defrauded investors by reporting misleading and unreasonable valuations of fund assets in order to charge excessive management and other fees. No. 19-cv-809, 2021 WL 719647, at *1 (W.D. Wis. Feb. 24, 2021). The court held that the statements were actionable, consistent with Omnicare, because “the SEC has alleged specific facts which, taken as true, involve valuations containing embedded statements of fact that were untrue.” Id. at *17. Specifically, defendants had stated that the valuations would be “based on underlying market driven events,” but the SEC alleged that the appraisal process was far less thorough. Id. This method, the court reasoned, “reflects the kind of ‘baseless, off-the-cuff judgment[]’ that an investor reasonably would not expect in the context of a third-party appraisal that is then relied upon in an investor fund’s financial statements.” Id.

As shareholder litigation arising from the economic impact of COVID-19 continues, including a handful of cases targeting vaccine development and efficacy, Omnicare will likely play a significant role. See Complaint for Violations of the Federal Securities Law, In re AstraZeneca PLC Sec. Litig., No. 1:21-cv-00722 (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 26, 2021) (containing various allegations based on statements or omissions relating to clinical trials for the COVID-19 vaccine). Disclosures and accounting estimates impacted by the rapidly evolving circumstances presented by the pandemic, and other statements and estimates involving interpretation of complex scientific data, are at the heart of Omnicare analysis. We will continue to monitor developments in these and similar cases.

VII. Halliburton II Market Efficiency and “Price Impact” Cases

As previewed in our last two updates, and discussed above in our Supreme Court roundup, the Supreme Court issued its decision in Goldman Sachs Group, Inc. v. Arkansas Teacher Retirement System on June 21. 141 S. Ct. 1951 (2021) (“Goldman Sachs”). Practitioners now have confirmation from the Supreme Court that courts must consider the generic nature of allegedly fraudulent statements at the class certification stage when necessary to determine whether the statements impacted the issuer’s stock price, even though that analysis will often overlap with the merits issue of materiality. See id. at 1960–61. The Court also resolved the question of which party bears what burden when defendants offer evidence of a lack of price impact to rebut the presumption of reliance, placing the burdens of both production and persuasion on defendants. See id. at 1962–63.

Recall that in Halliburton Co. v. Erica P. John Fund, Inc., 573 U.S. 258 (2014) (“Halliburton II”), the Supreme Court preserved the “fraud-on-the-market” presumption of class-wide reliance in Rule 10b-5 cases, but also permitted defendants to rebut this presumption at the class certification stage with evidence that the alleged misrepresentation did not impact the issuer’s stock price. Since that decision, as we have detailed in these updates, lower courts have struggled with several recurring questions, including: (1) how to reconcile Halliburton II with Erica P. John Fund, Inc. v. Halliburton Co., 563 U.S. 804 (2011) (“Halliburton I”) and Amgen Inc. v. Connecticut Retirement Plans and Trust Funds, 568 U.S. 455 (2013), in which the Court held that loss causation and materiality, respectively, were not class certification issues, but instead should be addressed at the merits stage; (2) who bears what burden when defendants present evidence of a lack of price impact; and (3) what evidence is sufficient to rebut the presumption. The Court has now resolved the first two questions in Goldman Sachs.

In its most recent decision, the Second Circuit held that the generic nature of Goldman Sachs’s allegedly fraudulent statements was irrelevant at the class-certification stage and instead should be litigated at trial, and that defendants bore both the burden of production and persuasion in rebutting the presumption of reliance. Ark. Tchr. Ret. Sys. v. Goldman Sachs Grp., Inc., 955 F.3d 254, 265–74 (2d Cir. 2020). As detailed above, the Supreme Court disagreed with the first holding but agreed with the second. Because it was unclear whether the Second Circuit properly considered Goldman Sachs’s price impact evidence, the Court remanded for further consideration. Goldman Sachs, 141 S. Ct. at 1961. The Court also confirmed that the Second Circuit allocated the parties’ burdens correctly, because the defendant “bear[s] the burden of persuasion to prove a lack of price impact by a preponderance of the evidence,” including at the class-certification stage. Id. at 1958. The Court clarified that its opinions had already placed that burden on defendants—although “the allocation of burden is unlikely to make much difference on the ground,” and will “have bite only when the court finds the evidence in equipoise.” Id. at 1963.

Most importantly, an eight-justice majority made clear that even when the question of price impact overlaps with merits questions, all relevant evidence on price impact must be considered at the class certification stage. Goldman Sachs, 141 S. Ct. at 1960–61 (citing Halliburton II, Comcast Corp. v. Behrend, 569 U.S. 27 (2013), and Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Dukes, 564 U.S. 338 (2011)). This is the case even though “materiality and price impact are overlapping concepts” and “evidence relevant to one will almost always be relevant to the other.” Id. at 1961 n.2. In other words, the Supreme Court has now confirmed that Halliburton I, Amgen, and Halliburton II are consistent because plaintiffs do not need to prove materiality and loss causation to invoke the presumption of reliance, but defendants can use price impact evidence—including evidence of immateriality or a lack of loss causation—to defeat the presumption of reliance at the class certification stage.

Despite its relevance to the case, the Court declined to offer a view on the validity of the inflation-maintenance theory, under which plaintiffs frequently argue that price movements associated with negative news can be attributed to earlier, challenged statements. See id. at 1959 n.1. However, the Court underscored that the connection between a statement and a corrective disclosure is particularly important in inflation-maintenance cases. Id. at 1961. As the Court noted, the inference that a subsequent price drop proves there was previous inflation “starts to break down when there is a mismatch between the contents of the misrepresentation and the corrective disclosure,” which can occur “when the earlier misrepresentation is generic . . . and the later corrective disclosure is specific.” Id.

The Second Circuit has now remanded to the district court to examine all relevant evidence of price impact in the first instance. Arkansas Tchr. Ret. Sys. v. Goldman Sachs Grp., Inc., No. 18-3667, 2021 WL 3776297, at *1 (2d Cir. Aug. 26, 2021). We will continue to monitor this and related cases.

VIII. Other Notable Developments

A. Morrison Domestic Transaction Test

The circuit split concerning the application of the domestic transaction test from Morrison v. National Australia Bank Ltd., 561 U.S. 247 (2010), has widened in the first half of this year. In Morrison, the Supreme Court held that the Exchange Act only applied to “transactions in securities listed on domestic exchanges, and domestic transactions in other securities.” Id. at 267. This holding was premised on “the focus of the Exchange Act,” which is “not upon the place where the deception originated, but upon purchases and sales of securities in the United States.” Id. at 266. Thereafter, courts have held that a security that is not traded on a domestic exchange satisfies the second prong of Morrison, “if irrevocable liability is incurred or title passes within the United States.” Absolute Activist Value Master Fund Ltd. v. Ficeto, 677 F.3d 60, 67 (2d Cir. 2012).

This January, in Cavello Bay Reinsurance Ltd. v. Shubin Stein, 986 F.3d 161 (2d Cir. 2021), the Second Circuit reaffirmed its prior holding in Parkcentral Global Hub Ltd. v. Porsche Automobile Holdings SE, 763 F.3d 198 (2d Cir. 2014), that the traditional “irrevocable liability” test is necessary, but not sufficient to bring a claim under the Exchange Act. Instead, a plaintiff must additionally show that the transaction was not “‘so predominantly foreign’ as to be impermissibly extraterritorial.” Cavello Bay, 986 F.3d at 165 (citing Parkcentral, 763 F.3d at 216). The Second Circuit considered that this test “uses Morrison’s focus on the transaction rather than surrounding circumstances, and flexibly considers whether a claim—in view of the security and the transaction as structured—is still predominantly foreign.” Id. at 166–67. Under this framework, the court affirmed the dismissal of an action based on “a private offering between a Bermudan investor . . . and a Bermudan issuer” because it was predominantly foreign, even though the fact that the contract was countersigned in the United States may have been sufficient to incur irrevocable liability in the United States. Id. at 167–68.

On the other hand, in its first application of Morrison, the First Circuit, “[l]ike the Ninth Circuit . . . reject[ed] Parkcentral as inconsistent with Morrison.” Sec. & Exch. Comm’n v. Morrone, 997 F.3d 52, 60 (1st Cir. 2021). Because “Morrison says that § 10(b)’s focus is on transactions,” the court found that “[t]he existence of a domestic transaction suffices to apply the federal securities laws under Morrison” and “[n]o further inquiry is required.” Id.

B. Eighth Circuit Strikes Class Allegations under Rule 12(f)

In Donelson v. Ameriprise Financial Services, Inc., 999 F.3d 1080 (8th Cir. 2021), the Eighth Circuit struck class allegations pursuant to Rule 12(f) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, which permits a court to strike from a pleading “any insufficient defense or any redundant, immaterial, impertinent, or scandalous matter.” Id. at 1091 (quoting Fed. R. Civ. P. 12(f)). The court “agree[d] with the Sixth Circuit that a district court may grant a motion to strike class-action allegations prior to the filing of a motion for class-action certification” when certification is a “clear impossibility,” noting that other federal courts have reached the conclusion that this was not permissible. Id. at 1092.

Donelson concerned an investor’s claims, including under Section 10(b) of the Securities Exchange Act, against a broker and investment advisor for mishandling and making misrepresentations about his investment account. Id. at 1086. The plaintiff sought to bring claims on behalf of a class of individuals who had allegedly suffered similar harms. While the agreement governing the plaintiff’s account contained a mandatory arbitration clause, there was an exception for “putative or certified class actions.” Id. The court found that the class allegations should be stricken because they were not “cohesive” and would require “a significant number of individualized factual and legal determinations to be made,” including specifically whether the defendants made misrepresentations to each investor, whether those misrepresentations were material, whether the investor relied upon them, and whether the investor suffered economic harm. Id. at 1092–93. Furthermore, the court found that the circumstances warranted striking the class allegations because delaying the inevitable decision would “needlessly force the parties to remain in court when they previously agreed to arbitrate.” Id. at 1092.

C. Congress Codifies SEC Disgorgement Remedy

On January 1, 2021, Congress codified the SEC’s right to disgorgement remedies as part of the National Defense Authorization Act (“NDAA”). While the SEC has often sought—and courts have often granted—disgorgement remedies, the new law codifies this right and also adds guidance as to the parameters. Section 6501 of the NDAA amends the Exchange Act to allow any United States District Court to “require disgorgement…of any unjust enrichment by the person who received such unjust enrichment as a result of [violations under the securities laws].” Previously, disgorgement was awarded pursuant to the court’s equitable power, rather than statutorily mandated in cases of unjust enrichment.

Significantly, the amendment also provides for a 10-year statute of limitations that applies to “[any actions for disgorgement arising out] of the securities laws for which scienter must be established.” 15 U.S.C. § 78u(d)(8)(A)(ii). The law further provides for a 10-year statute of limitations for “any equitable remedy, including for an injunction or for a bar, suspension, or cease and desist order” irrespective of whether the underlying securities law violation carries a scienter requirement. 15 U.S.C. § 78u(d)(8)(B). The law expands disgorgement to “any equitable remedy” and ensures that a court awards disgorgement in these cases. Moreover, for the purposes of calculating any limitations period under this paragraph, “any time in which the person . . . is outside of the United States shall not count towards the accrual of that period.” 15 U.S.C. § 78u(d)(8)(C).

D. Delaware Exclusive Forum Bylaws Applicable to Section 14

A recent federal decision in the Northern District of California precluded plaintiffs from bringing Section 14(a) claims in the face of an exclusive forum selection clause in a company’s bylaws. Lee v. Fisher, 2021 WL 1659842 (N.D. Cal. Apr. 27, 2021). In Lee, plaintiffs brought derivative claims on behalf of The Gap, Inc. for violation of Section 14(a) of the Securities Exchange Act as a result of allegedly misleading statements about the Gap’s commitment to diversity. Id. at *1. The defendants moved to dismiss the claims on forum non conveniens grounds based on the forum selection clause in Gap’s bylaws, which provided that any action had to be brought in Delaware Chancery Court. Id. at *2. In granting the motion and dismissing the claims, the court noted a strong policy in favor of enforcing forum selection clauses where practicable. Id. at *3. In response to the plaintiff’s objection that Section 14(a) claims must be asserted in federal court because of its exclusive jurisdiction and that the anti-waiver provisions in the Securities Act preclude waiving the jurisdictional requirement, the court noted Ninth Circuit precedent has held that the policy of enforcing forum selection clauses supersedes anti-waiver provisions like those in the Exchange Act. Id. In addition, enforcement of the exclusive forum selection clause would not leave the plaintiff without a remedy because the plaintiff could file separate state law derivative claims in Delaware, even if such action could not include a federal securities law claim. The plaintiffs have filed a notice of appeal in the Ninth Circuit.

E. Ninth Circuit Upholds Broad Protection for Forward-Looking Statements

In Wochos v. Tesla, Inc., 985 F.3d 1180 (9th Cir. 2021), the Ninth Circuit upheld a broad interpretation of the safe harbor protections afforded by the PSLRA. The PSLRA’s safe harbor for forward-looking statements protects against liability that is premised upon statements made about a company’s plans, objectives, and projections of future performance, along with the assumptions underlying such statements. In Wochos, the Ninth Circuit held that this protection applies even when the statements touch on the current state of affairs.

The plaintiffs in Wochos alleged that statements by Tesla officers that the company was “on track” to meet certain production goals was misleading because the company was facing manufacturing problems that made these production goals difficult to attain. Id. at 1185–86. Plaintiffs claimed that the statements were not protected under the PSLRA’s safe harbor provisions because these “predictive statements contain[ed] embedded assertions concerning present facts that are actionable.” Id. at 1191 (emphasis in original). The court disagreed, finding that the definition of forward-looking statements “expressly includes ‘statement[s] of the plans and objectives of management for future operations,’” and “‘statement[s] of the assumptions underlying or relating to’ those plans and objectives.” Id. (emphases in original). Even though Tesla’s statements touched on the current state of the business, the court found that they were forward-looking because “any announced ‘objective’ for ‘future operations’ necessarily reflects an implicit assertion that the goal is achievable based on current circumstances.” Id. at 1192 (emphasis in original). The court reasoned that the safe harbor would be rendered moot if it “could be defeated simply by showing that a statement has the sort of features that are inherent in any forward-looking statement.” Id. (emphasis in original).

The following Gibson Dunn attorneys assisted in preparing this client update: Jeff Bell, Shireen Barday, Monica Loseman, Brian Lutz, Mark Perry, Avi Weitzman, Lissa Percopo, Michael Celio, Alisha Siqueira, Rachel Jackson, Andrew Bernstein, Megan Murphy, Jonathan D. Fortney, Sam Berman, Fernando Berdion-Del Valle, Andrew V. Kuntz, Colleen Devine, Aaron Chou, Luke Dougherty, Lindsey Young, Katy Baker, Jonathan Haderlein, Marc Aaron Takagaki, and Jeffrey Myers.

Gibson Dunn lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding these developments. Please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, the authors, or any of the following members of the Securities Litigation practice group:

Monica K. Loseman – Co-Chair, Denver (+1 303-298-5784, mloseman@gibsondunn.com)

Brian M. Lutz – Co-Chair, San Francisco/New York (+1 415-393-8379/+1 212-351-3881, blutz@gibsondunn.com)

Craig Varnen – Co-Chair, Los Angeles (+1 213-229-7922, cvarnen@gibsondunn.com)

Shireen A. Barday – New York (+1 212-351-2621, sbarday@gibsondunn.com)

Jefferson Bell – New York (+1 212-351-2395, jbell@gibsondunn.com)

Matthew L. Biben – New York (+1 212-351-6300, mbiben@gibsondunn.com)

Michael D. Celio – Palo Alto (+1 650-849-5326, mcelio@gibsondunn.com)

Paul J. Collins – Palo Alto (+1 650-849-5309, pcollins@gibsondunn.com)

Jennifer L. Conn – New York (+1 212-351-4086, jconn@gibsondunn.com)

Thad A. Davis – San Francisco (+1 415-393-8251, tadavis@gibsondunn.com)

Ethan Dettmer – San Francisco (+1 415-393-8292, edettmer@gibsondunn.com)

Mark A. Kirsch – New York (+1 212-351-2662, mkirsch@gibsondunn.com)

Jason J. Mendro – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3726, jmendro@gibsondunn.com)

Alex Mircheff – Los Angeles (+1 213-229-7307, amircheff@gibsondunn.com)

Robert F. Serio – New York (+1 212-351-3917, rserio@gibsondunn.com)

Robert C. Walters – Dallas (+1 214-698-3114, rwalters@gibsondunn.com)

Avi Weitzman – New York (+1 212-351-2465, aweitzman@gibsondunn.com)

© 2021 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP

Attorney Advertising: The enclosed materials have been prepared for general informational purposes only and are not intended as legal advice.