In a sweeping victory for speech rights against overreach by state officials, Gibson Dunn and Elias Law Group convinced a D.C. federal court to enjoin an investigation by Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton into Media Matters, a non-profit research and information center that reports on misinformation and political extremism in the U.S. media. On November 16, 2023, Media Matters published a post reporting that ads for Apple, Bravo, IBM, Oracle, and Xfinity were showing up next to antisemitic content on X (formerly Twitter). In response, X’s owner Elon Musk posted that he would bring a “thermonuclear lawsuit” against Media Matters, filing suit on November 30, 2023 in the Northern District of Texas—despite Media Matters being located in Washington, D.C.

Virtually simultaneously, Texas AG Paxton opened an investigation of Media Matters for potential fraudulent activity in violation of Texas’s Deceptive Trade Practices Act (DTPA). Invoking the DTPA’s authority, Paxton served a broad and intrusive Civil Investigative Demand (CID) upon Media Matters, seeking a broad array of records relating to Media Matters’s reporting, funding, and reporter and editorial communications—despite Media Matters’s lack of any relevant connection to Texas. Gibson Dunn and Elias Law Group sought a preliminary injunction in the D.C. federal court, arguing that Paxton lacked jurisdiction to issue and enforce the CID, that the CID was a retaliatory action for speech in violation of the First Amendment, and that the overbroad document requests violated D.C. and Maryland reporters’ shield laws. Enforcement of the CID had chilled and would further chill Media Matters’s core First Amendment-protected speech, the motion argued, and was a direct assault on its newsgathering function.

The United States District Court for D.C. ruled in favor of Media Matters, issuing a preliminary injunction enjoining Paxton and his office from enforcing the CID. The court ruled that it had personal jurisdiction over Paxton under D.C.’s long-arm statute, that Media Matters had suffered cognizable First Amendment injury, that D.C. was the right venue, and that plaintiffs have proven a likelihood of success on the merits, noting that the threat of administrative intrusion into the newsgathering process would likely deter protected speech and undermine newsgathering and reporting in violation of the First Amendment. The victory sets valuable precedent for journalistic outfits and other entities targeted by overreaching out-of-state AGs, allowing them to fight back without having to submit to the jurisdiction of the AG’s home state.

The Gibson Dunn team includes partners Ted Boutrous (Los Angeles), Amer S. Ahmed (New York), Anne Champion (New York), and Jay Srinivasan (Los Angeles), as well as New York associates Iason Togias and Apratim Vidyarthi.

In this recorded webcast, seasoned practitioners from Gibson Dunn’s Corporate and Antitrust practices discuss best practices and the latest developments in joint venture formation and operation, including:

1. Hot-button operating agreement provisions

2. Navigating transfer and exit considerations

3. Designing antitrust-compliant contractual provisions

4. Analysis and ramifications from recent antitrust enforcement actions

PANELISTS:

Robert B. Little is a partner in Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher’s Dallas office, and he is a Global Co-Chair of the Mergers and Acquisitions Practice Group. Mr. Little has consistently been named among the nation’s top M&A lawyers every year since 2013 by Chambers USA. His practice focuses on corporate transactions, including mergers and acquisitions, securities offerings, joint ventures, investments in public and private entities, and commercial transactions. Mr. Little has represented clients in a variety of industries, including energy, retail, technology, infrastructure, transportation, manufacturing and financial services.

Christopher M. Wilson is a partner in Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher’s Washington, D.C. office and a member of the firm’s Antitrust and Competition Practice Group. Mr. Wilson assists clients in navigating DOJ, FTC, and international competition authority investigations as well as private party litigation involving complex antitrust and consumer protection issues, including matters implicating the Sherman Act, the Clayton Act, the FTC Act, the Hart-Scott-Rodino (HSR) merger review process, as well as international and state competition statutes. His experience crosses multiple industries and his particular areas of focus include merger enforcement, interlocking directorates, joint ventures, compliance programs, and employee “no-poach” agreements.

Taylor Hathaway-Zepeda is a partner in the Los Angeles office of Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher. Her practice focuses on mergers, acquisitions, divestitures, joint ventures, equity investments, restructuring transactions and general corporate governance. She works with companies in a broad array of industries, and has extensive experience working with media, entertainment and technology companies and private equity sponsors. Ms. Hathaway-Zepeda currently serves on the Board of Directors of the California Chamber of Commerce and the Board of Directors of the Los Angeles Area Chamber of Commerce, where she is also Chair of the Governance Committee.

MCLE CREDIT INFORMATION:

This program has been approved for credit in accordance with the requirements of the New York State Continuing Legal Education Board for a maximum of 1.0 credit hour, of which 1.0 credit hour may be applied toward the areas of professional practice requirement. This course is approved for transitional/non-transitional credit.

Attorneys seeking New York credit must obtain an Affirmation Form prior to watching the archived version of this webcast. Please contact CLE@gibsondunn.com to request the MCLE form.

Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP certifies that this activity has been approved for MCLE credit by the State Bar of California in the amount of 1.0 hour.

California attorneys may claim “self-study” credit for viewing the archived version of this webcast. No certificate of attendance is required for California “self-study” credit.

© 2024 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP. All rights reserved. For contact and other information, please visit us at www.gibsondunn.com.

Attorney Advertising: These materials were prepared for general informational purposes only based on information available at the time of publication and are not intended as, do not constitute, and should not be relied upon as, legal advice or a legal opinion on any specific facts or circumstances. Gibson Dunn (and its affiliates, attorneys, and employees) shall not have any liability in connection with any use of these materials. The sharing of these materials does not establish an attorney-client relationship with the recipient and should not be relied upon as an alternative for advice from qualified counsel. Please note that facts and circumstances may vary, and prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome.

On April 20, 2024, New York lawmakers approved the State’s 2024-2025 budget. As a part of the budgetary vote, lawmakers passed three notable amendments to New York Labor Law of which employers should be aware.

PAID PRENATAL LEAVE: In a first-of-its-kind law in the country, lawmakers amended the New York Labor Law’s sick leave provisions to require all employers (regardless of size) to provide employees twenty (20) hours of paid prenatal leave per year. Employees may use this leave to obtain healthcare services during or related to pregnancy – for example, for physical examinations, medical procedures, monitoring and testing, and discussions with a health care provider concerning their pregnancy.

This leave bank must be separate from other leave accruals, including the forty (40) or fifty-six (56)[1] hours of sick leave that New York employers are currently required to provide employees for their own illness or need for medical care (including mental illness), the care or treatment of certain covered family members, and for certain safety concerns (such as domestic violence).

The law prohibits employers from discriminating or retaliating against employees because they requested or utilized prenatal leave and requires employees who use prenatal leave to be restored to the same position they held prior to such leave. The amendment does not address, for example, whether and under what circumstances employers may require advance notice or documentation regarding the use of prenatal leave, though the labor commissioner has the authority to adopt regulations and issue guidance to address these and other questions. The requirements to provide prenatal leave become effective on January 1, 2025.

PAID NURSING BREAKS: The New York Labor Law was also amended to require all employers (regardless of size) to provide paid nursing breaks. This marks a notable change from the current law, which only requires reasonable unpaid breaks for expressing breast milk. Under the new law, which is effective June 19, 2024, employers must provide thirty (30) minute paid breaks each time an employee has a reasonable need to express breast milk for up to three (3) years following childbirth. The law also requires employers to permit employees to use other existing paid break and mealtime (e.g., under wage and hour laws) to express breast milk when breaks longer than thirty (30) minutes are needed.

The statute does not address how often employees may take paid nursing breaks. However, the state interpreted the prior iteration of the statute to allow employees to take unpaid breaks at least once every three hours, with accommodations made for employees that need more frequent breaks. The state might take a similar approach with the new iteration of the law requiring paid breaks.

COVID-19 SICK LEAVE: Finally, New York’s COVID-19 leave law will be deemed repealed as of July 31, 2025. The State’s COVID-19 leave law presently requires employers to provide employees up to fourteen (14) days of paid leave, separate from other leave accruals, when they are subject to a mandatory or precautionary order of quarantine or isolation due to COVID-19. Although employees with COVID-19 may still qualify for leave under the State’s sick leave law after July 31, 2025, New York employers will no longer be required to provide a separate COVID-19 leave bank after that date.

New York employers should review and revise their existing leave and break policies to ensure compliance with these new requirements by the effective dates.

__________

[1] The State’s sick leave law currently requires: (i) employers with one hundred (100) or more employees to provide fifty-six (56) hours of paid sick leave per year; (ii) employers with between five (5) and ninety-nine (99) employees to provide forty (40) hours of paid sick leave per year; and (iii) employers with less than five (5) employees to provide forty (40) hours of unpaid sick leave per year, unless the employer has a net income of greater than $1 million per year, in which case, such sick leave must be paid.

Gibson Dunn’s lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding these developments. To learn more about these issues, please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, any member of the firm’s Labor and Employment practice group, or the following authors:

Harris M. Mufson – Partner, New York (+1 212.351.3805, hmufson@gibsondunn.com)

Danielle J. Moss – Partner, New York (+1 212.351.6338, dmoss@gibsondunn.com)

Jason C. Schwartz – Co-Chair, Washington, D.C. (+1 202.955.8242, jschwartz@gibsondunn.com)

Katherine V.A. Smith – Co-Chair, Los Angeles (+1 213.229.7107, ksmith@gibsondunn.com)

*Andrew Webb, a recent law graduate in the New York office, is not admitted to practice law.

© 2024 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP. All rights reserved. For contact and other information, please visit us at www.gibsondunn.com.

Attorney Advertising: These materials were prepared for general informational purposes only based on information available at the time of publication and are not intended as, do not constitute, and should not be relied upon as, legal advice or a legal opinion on any specific facts or circumstances. Gibson Dunn (and its affiliates, attorneys, and employees) shall not have any liability in connection with any use of these materials. The sharing of these materials does not establish an attorney-client relationship with the recipient and should not be relied upon as an alternative for advice from qualified counsel. Please note that facts and circumstances may vary, and prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome.

This near categorical ban on non-compete agreements marks an abrupt departure from existing law in many jurisdictions and has drawn almost immediate legal challenges.

On April 23, 2024, the FTC voted 3-2 to adopt a sweeping final rule banning the use of non-compete agreements nationwide, impacting 30 million workers by the FTC’s own estimates.[1] The final rule is presently set to become effective 120 days after its publication in the Federal Register, which is expected to occur in the next two weeks, with the possibility that the effective date may be delayed or enjoined in light of the pending litigation challenging the rule. It prohibits any new non-compete agreements and renders existing non-compete agreements with workers unenforceable, with limited exceptions. In addition to banning new non-competes, the rule requires employers to provide workers with notice that their existing non-compete agreements are no longer enforceable, but employers are not required to formally rescind the agreements.[2] Employers should be aware that the rule defines “worker” broadly, encompassing persons working as employees, independent contractors, interns, externs, volunteers, and sole proprietors.[3]

This near categorical ban on the non-compete agreements is an abrupt contrast from a regime in which these agreements had been recognized to have potential procompetitive value and therefore were reviewed for reasonableness. It also marks a sharp departure from the state law in many jurisdictions.

I. Narrow Exceptions

Notably, the final rule does not invalidate existing non-compete agreements with senior executives, one of the few changes from the proposed rule.[4] A “senior executive” is defined as a worker who: (1) earns more than $151,164 annually; and (2) is in a “policy-making position,” which is defined narrowly to mean “a business entity’s president, chief executive officer or the equivalent, any other officer of a business entity who has policy-making authority, or any other natural person who has policy-making authority for the business entity similar to an officer with policy-making authority.” The final rule also does not bar causes of action related to a non-compete that accrued prior to the effective date of the final rule. And enforcing or attempting to enforce a non-compete is not considered an unfair method of competition where an employer has a good-faith basis to believe the final rule is inapplicable.

The final rule’s general prohibition on non-competes is also not applicable to non-competes entered pursuant to the sale of a business. While the Commission had earlier proposed an exception for certain non-competes between the seller and the buyer of a business that applied only to a substantial owner, member, or partner, defined as an owner, member, or partner with at least 25% ownership interest in the business entity being sold, in response to public comments, the final rule no longer includes the proposed requirement that the restricted party be “a substantial owner of, or substantial member or substantial partner in, the business entity” to fall under the exception.

II. Functional Non-Competes

The final rule defines a “non-compete clause” as “a term or condition of employment that prohibits a worker from, penalizes a worker for, or functions to prevent a worker from (1) seeking or accepting work in the United States with a different person where such work would begin after the conclusion of the employment that includes the term or condition; or (2) operating a business in the United States after the conclusion of the employment that includes the term or condition.” In assessing the impact of the final rule on other kinds of restrictive covenants, the FTC emphasizes three prongs of the “non-compete clause” definition—”prohibit,” “penalize,” and “functions to prevent.” Although the FTC declined to create a categorical prohibition on non-disclosure, non-solicitation, and similar restrictive covenants, it explained that the “functions to prevent” language applies to any term or condition of employment adopted by an employer that is so broad or onerous as to have the same functional effect as a term or condition prohibiting or penalizing a worker from seeking or accepting other work or starting a business after their employment ends.

The FTC explained its view that a “garden-variety NDA,” in which a worker agrees not to disclose certain confidential information to a competitor, would not prevent that worker from seeking or accepting work with a competitor after leaving their job. However, the FTC would consider an NDA that spans such a wide swath of information so as to functionally prevent a worker from seeking or accepting other work to be a “non-compete clause.” Examples of problematic NDAs provided by the final rule include: (1) an agreement barring a worker from disclosing any information “usable in” or relating to the industry in which they work; and (2) an agreement barring a worker from disclosing any information obtained during their employment, including publicly available information.

Non-solicitation agreements and training repayment provisions are subject to the same fact-specific analysis. In particular, the FTC stated that agreements that impose substantial out-of-pocket costs upon workers for departing may effectively prevent them from seeking or accepting other work or starting a business and be functionally deemed a non-compete agreement.

The FTC also clarified that in its view a “garden leave” agreement—where the worker is “still employed and receiving the same total annual compensation and benefits on a pro rata basis—is not a non-compete clause,” since such an agreement does not restrict the worker post-employment. For the same reason, the FTC explained that the final rule is not meant to prohibit agreements under which a worker who does not meet a condition foregoes a particular aspect of their expected compensation, which would seemingly remove retention bonuses from the rule’s purview. Similarly, the FTC stated that agreements requiring workers to repay a bonus or forfeit accrued sick leave after leaving a job would not meet the definition of “non-compete clause” under the final rule, so long as they do not penalize or function to prevent a worker from seeking or accepting work or operating a business after the worker leaves the job.

III. Republican Dissents

Yesterday’s Special Open Commission Meeting marked the first for incoming Republican Commissioners Melissa Holyoak and Andrew Ferguson, who both dissented on constitutional and statutory grounds, among other reasons. Although their written dissents are not yet available, they stated in oral remarks[5] that the final rule exceeds the FTC’s authority and is barred by the major questions doctrine because Congress did not authorize the FTC to promulgate legislative rules (much less rules of such sweeping consequence) through either Section 6(g) or Section 5 of the FTC Act. According to Commissioner Ferguson, the FTC majority relies on “oblique or elliptical language that cannot justify the redistribution of half a trillion dollars of wealth within the general economy by regulatory fiat.” Commissioner Ferguson further stated the Rule is (1) unlawful under the non-delegation doctrine, and (2) arbitrary and capricious under the Administrative Procedure Act because the evidence on which the agency relies cannot justify the nationwide ban of non-competes irrespective of their terms, conditions, and particular effects.

IV. Immediate Legal Challenges

Within minutes of the vote, the final rule was the subject of a legal challenge filed by Gibson Dunn in the Northern District of Texas. Consistent with the dissenting views of Commissioners Holyoak and Ferguson, Gibson Dunn’s complaint argues that the FTC lacks the statutory authority to issue the rule, that any such grant of authority would be an unconstitutional delegation of legislative power, and that the FTC is unconstitutionally structured. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce also filed a lawsuit today. These cases raise the substantial questions surrounding the FTC’s authority to promulgate rules in this area and whether the agency’s rulemaking complied with the Administrative Procedure Act.

V. Employer Considerations

The final rule is presently set to become effective 120 days after its publication in the Federal Register. Given the pending litigation challenging the rule, it is possible that this effective date may be delayed or enjoined, and that the rule may ultimately be invalidated and never take effect. Accordingly, employers have, at a minimum, several months before the rule takes effect and may find it appropriate to watch how the pending legal challenges develop. Notwithstanding that uncertainty, however, businesses subject to the final rule[6] should consider using this time to: (1) review their existing non-compete agreements and be prepared to provide the required notice to non-senior executive workers, in accordance with the rule’s requirements, if and when necessary; (2) likewise, be prepared if necessary to amend existing antitrust compliance programs to provide guidance to avoid violating the rule; (3) consult with outside counsel; and (4) carefully consider the potential impact on future mergers and acquisitions, as the Hart-Scott-Rodino Act rules proposed by the FTC last year require disclosure of transaction-related agreements (including non-competes).

Gibson Dunn attorneys are closely monitoring these developments and available to discuss these issues as applied to your particular business.

__________

[1] The text of the FTC’s “Non-Compete Clause Rule” is available here.

[2] The rule includes model language that satisfies this notice requirement.

[3] The definition also includes persons working for a franchisee or franchisor but does not extend to a “franchisee” in the context of a franchisee-franchisor relationship.

[4] The FTC estimates that fewer than 0.75% of workers will qualify as senior executives according to the rule.

[5] A recording of the Special Open Commission Meeting is available here.

[6] The FTC stated that the “final rule applies to the full scope” of its jurisdiction, which it stated would exclude many non-profits. However, the preamble makes clear that the FTC will not treat an organization’s tax-exempt status as dispositive for purposes of evaluating its authority. Section 5 of the FTC Act also does not apply to the following entities: banks, savings and loan institutions, federal credit unions, common carriers, air carriers, and persons and businesses subject to the Packers and Stockyards Act.

Gibson Dunn’s lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding the issues discussed in this update. Please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, the authors, any leader or member of the firm’s Labor and Employment, Administrative Law and Regulatory, or Antitrust and Competition practice groups, or the following:

Labor and Employment:

Andrew G.I. Kilberg – Partner, Washington, D.C. (+1 202.887.3759, akilberg@gibsondunn.com)

Karl G. Nelson – Partner, Dallas (+1 214.698.3203, knelson@gibsondunn.com)

Jason C. Schwartz – Co-Chair, Washington, D.C. (+1 202.955.8242, jschwartz@gibsondunn.com)

Katherine V.A. Smith – Co-Chair, Los Angeles (+1 213.229.7107, ksmith@gibsondunn.com)

Administrative Law and Regulatory:

Eugene Scalia – Co-Chair, Washington, D.C. (+1 202.955.8673, escalia@gibsondunn.com)

Helgi C. Walker – Co-Chair, Washington, D.C. (+1 202.887.3599, hwalker@gibsondunn.com)

Antitrust and Competition:

Rachel S. Brass – Co-Chair, San Francisco (+1 415.393.8293, rbrass@gibsondunn.com)

Svetlana S. Gans – Partner, Washington, D.C. (+1 202.955.8657, sgans@gibsondunn.com)

Cynthia Richman – Co-Chair, Washington, D.C. (+1 202.955.8234, crichman@gibsondunn.com)

Stephen Weissman – Co-Chair, Washington, D.C. (+1 202.955.8678, sweissman@gibsondunn.com)

Chris Wilson – Partner, Washington, D.C. (+1 202.955.8520, cwilson@gibsondunn.com)

© 2024 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP. All rights reserved. For contact and other information, please visit us at www.gibsondunn.com.

Attorney Advertising: These materials were prepared for general informational purposes only based on information available at the time of publication and are not intended as, do not constitute, and should not be relied upon as, legal advice or a legal opinion on any specific facts or circumstances. Gibson Dunn (and its affiliates, attorneys, and employees) shall not have any liability in connection with any use of these materials. The sharing of these materials does not establish an attorney-client relationship with the recipient and should not be relied upon as an alternative for advice from qualified counsel. Please note that facts and circumstances may vary, and prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome.

Gibson Dunn’s Workplace DEI Task Force aims to help our clients develop creative, practical, and lawful approaches to accomplish their DEI objectives following the Supreme Court’s decision in SFFA v. Harvard. Prior issues of our DEI Task Force Update can be found in our DEI Resource Center. Should you have questions about developments in this space or about your own DEI programs, please do not hesitate to reach out to any member of our DEI Task Force or the authors of this Update (listed below).

Key Developments:

On April 17, 2024, the Supreme Court held in Muldrow v. City of St. Louis, No. 22-193, that plaintiffs who challenge employers’ job transfer decisions as discriminatory under Title VII do not need to demonstrate that the harm suffered was “significant,” “material,” or “serious.” But plaintiffs must still show “some harm respecting an identifiable term or condition of employment,” such as hiring, firing, or transferring employees. A plaintiff also must show that her employer acted with discriminatory intent and that the transfer was based on a characteristic protected under Title VII. The Court emphasized that the decision does not reach retaliation or hostile work environment claims. The Court did not address how the decision might impact corporate DEI programs. For a more detailed discussion of this decision, see our April 17 Client Alert .

On April 12, 2024, Arkansas teachers and students, along with the Arkansas State Conference of the NAACP (NAACP-AR), filed a complaint against Governor Sarah Huckabee Sanders, challenging the constitutionality of Section 16 of Arkansas’s Literacy, Empowerment, Accountability, Readiness, Networking and School Safety Act (the “LEARNS Act”) and seeking to enjoin its enforcement. In Walls v. Sanders, No. 4:24-cv-002 (E.D. Ark. April 12, 2024), the plaintiffs allege that the LEARNS Act “expressly bans” the teaching of “Critical Race Theory” (which the Act refers to as “forced indoctrination”) in violation of their First Amendment and Fourteenth Amendment rights. After the Act was passed, Arkansas Secretary of Education Jacob Oliva revoked state approval for the AP African American Studies course, alleging that the course and educational materials violated Section 16. The plaintiffs allege that Section 16 chills speech, impermissibly regulates speech based on viewpoint discrimination, and violates the equal protection guarantees of the Fourteenth Amendment because it was motivated by racial animus and “created, in part, to target Black students and educators on the basis of race.” On April 17, 2024, the court denied the plaintiffs’ request for expedited briefing but scheduled a preliminary injunction hearing for April 30, 2024.

April continues to be a busy month for state legislation on both sides of the DEI debate. On April 22, 2024, Tennessee Governor Bill Lee signed H.B. 2100—a “social credit score” bill—into law. The bill limits factors that insurers and financial institutions can consider in decisions about the provision or denial of services. Specifically, the bill prohibits insurers and financial institutions from denying services or otherwise discriminating against persons for failure to satisfy ESG standards, corporate composition benchmarks, or compliance with DEI training policies. Meanwhile, on April 8, 2024, Virginia Governor Glenn Youngkin signed H.B. 1452 into law. This new law takes effect on July 1, 2024, and will require state agency heads to maintain comprehensive diversity, equity, and inclusion strategic plans. Strategic plans will need to integrate DEI goals into each agency’s mission and detail best practices for addressing equal opportunity barriers and promoting equity in operational activities including pay, hiring, and leadership. Agencies will be required to submit annual reports to enable the Governor and the General Assembly to monitor progress.

Media Coverage and Commentary:

Below is a selection of recent media coverage and commentary on these issues:

-

- The Wall Street Journal, “Diversity goals are disappearing from companies’ annual reports” (April 21): The Wall Street Journal’s Ben Glickman and Lauren Weber report on shifts in how companies are discussing DEI in their annual reports as a result of increased scrutiny of DEI initiatives. Glickman and Weber conclude that “[d]ozens of companies [have] altered descriptions of diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives in their annual reports to investors,” citing several examples. Glickman and Weber note that these shifts do not necessarily mean companies are abandoning their commitment to DEI, just that they are choosing to be less public about their DEI programs. Ivy Feng, an accounting professor at the University of Wisconsin, observed, “What gets disclosed gets managed. So if they don’t say anything, it’s more difficult for outsiders to find out what’s really going on.” Jason Schwartz, Gibson Dunn partner and co-head of the firm’s Labor and Employment practice group, concludes that many companies are just trying to determine what is lawful: “Forget about any ideological agenda. [Companies are] just trying to figure out, how do I follow the law? You don’t want to overcommit or undercommit or misdescribe where you’ll eventually land.”

- The Washington Post, “DEI ‘lives on’ after Supreme Court ruling, but critics see an opening” (April 19): Julian Mark of The Washington Post writes on the potential impact on DEI programs following the Supreme Court’s decision in Muldrow v. City of St. Louis, Missouri. Mark notes the divergence of views on the scope of the Court’s ruling. Some practitioners interpret Muldrow narrowly. But EEOC Commissioner Andrea Lucas contends that DEI programs are now more susceptible to legal challenges than ever. Lucas asserts leadership development or training programs that are restricted to certain racial groups are now “high risk,” as are employers’ efforts to foster diverse hiring slates, opining that “the ‘some harm’ standard will [not] be the saving grace for a DEI program.”

- Bloomberg Law, “The Supreme Court Just Complicated Employer DEI Programs” (April 18): Writing for Bloomberg Law, Simon Foxman examines the Supreme Court’s ruling in Muldrow v. City of St. Louis, Missouri, in which the Supreme Court unanimously held that an employee could bring suit under Title VII based on her reassignment to a position of the same pay but less favorable workdays and other benefits. The Court explained that an employee only has to suffer “‘some harm’ under the terms of their employment,” but that harm “doesn’t need to be ‘material,’ ‘substantial’ or ‘serious.’” Foxman reports that racial justice groups like the Legal Defense Fund celebrated the decision but expressed fears that “opponents of DEI programs likely will see this as an opening to launch new attacks on diversity programs.”

-

- The New York Times, “What Researchers Discovered When They Sent 80,000 Fake Résumés to U.S. Jobs” (April 8): Claire Cain Miller and Josh Katz of The New York Times report on a social experiment performed by a group of economists on roughly 100 of the largest companies in the country. The economists submitted thousands of fake “résumés with equivalent qualifications but different personal characteristics,” changing the name on each application to suggest whether an applicant was “white or Black, and male or female.” Miller and Katz report that the results were striking, with one company contacting “presumed white applicants 43 percent more often” than minority applicants with the same credentials. The study identifies other trends, including potential biases against older workers, women, and LGBTQ individuals. Miller and Katz note the study found various measures companies use in an effort to reduce discrimination, such has employing a chief diversity officer, offering diversity training, or having a diverse board, had no effect on the outcome of their experiment. But there was one thing all the companies who exhibited the least bias had in common: a centralized human resources function.

- The New York Times, “With State Bans on D.E.I., Some Universities Find a Workaround: Rebranding” (April 12): Writing for The New York Times, Stephanie Saul reports on what she terms the “rebranding” many state universities have undertaken in the wake of legislation targeting DEI programs in higher education. Saul writes that, as an example, the University of Tennessee’s “campus D.E.I. program is now called the Division of Access and Engagement,” and at LSU, what was once the Division of Inclusion, Civil Rights and Title IX is now called the Division of Engagement, Civil Rights and Title IX. Saul states that some, like LSU VP of Marketing Todd Woodward, celebrate this “rebranding” as an effort to retain the impact of the departments and avoid job cuts. Woodward explained that the switch from “inclusion” to “engagement” better signifies the “university’s strategic plan.” But others, like Professor David Bray at Kennesaw State University, express skepticism, saying moves like this are little more than “the same lipstick on the ideological pig.”

-

- AP News, “Texas diversity, equity and inclusion ban has led to more than 100 job cuts at state universities” (April 13): Writing for AP News, Acacia Coronado examines the effect that SB17, Texas’ ban on DEI initiatives, has had in higher education. According to Coronado, the bill, which prohibits training and activities that reference race, color, ethnicity, gender identity, or sexual orientation, “has led to more than 100 job cuts across university campuses in Texas.” SB17 does not “apply to academic course instruction and scholarly research” positions, but Professor Aquasia Shaw, the only person of color in the Kinesiology Department at the University of Texas at Austin, suspects SB17 was responsible for the University’s decision not to renew her contract.

- The Hill, “Republican states urge Congress to reject DEI legislation” (April 16): The Hill’s Cheyanne Daniels reports on Representatives Ayanna Pressley (D-MA) and Jamie Raskin’s (D-MD) introduction of the Federal Government Equity Improvement and Equity in Agency Planning Acts in the wake of “attempts to limit DEI programs . . . around the country.” These bills are designed to encourage federal agencies to enact policies focused on “providing equal opportunity for all, including people of color, women, rural communities and individuals with disabilities.” The legislation has not been welcomed by all, with Republican West Virginia Attorney General Patrick Morrisey penning a letter to Raskin and Representative James Comer (R-KY), Chairman of the Committee on Oversight and Accountability, declaring the bills “divisive.”

- Law360, “Anti-DEI Complaints Filed With EEOC Carry No Legal Weight” (April 15): In an op-ed for Law360, Rutgers law professor and former EEOC counsel David Lopez asserts that the series of EEOC complaints conservative organizations like America First Legal Foundation (“AFL”) are filing against companies “carry no legal weight.” He describes these complaints as mere attempts to “weaponize the [public’s] lack of knowledge as a means of bullying employers into retreating from core values.” He encourages employers “not [to] be intimidated” by AFL’s tactics but to continue “develop[ing] workplace practices focused on rooting out entrenched and ongoing discriminatory practices against Black people, women and others in the workplace.”

Case Updates:

Below is a list of updates in new and pending cases:

1. Contracting claims under Section 1981, the U.S. Constitution, and other statutes:

- Suhr v. Dietrich, No. 2:23-cv-01697-SCD (E.D. Wis. 2023): On December 19, 2023, a dues-paying member of the Wisconsin Bar filed a complaint against the Bar over its “Diversity Clerkship Program,” a summer hiring program for first-year law students. The program’s application requirements had previously stated that eligibility was based on membership in a minority group. After SFFA v. Harvard, the eligibility requirements were changed to include students with “backgrounds that have been historically excluded from the legal field.” The plaintiff claims that the Bar’s program is unconstitutional even with the new race-neutral language, because, in practice, the selection process is still based on the applicant’s race or gender. The plaintiff also alleges that the Bar’s diversity program constitutes compelled speech and compelled association in violation of the First Amendment.

- Latest update: Under a partial settlement agreement, the Bar agreed to “make clear that the Diversity Clerkship Program is open to all first-year law students.” In exchange, the plaintiff will drop his claims about the clerkship program and file an amended lawsuit challenging only the mandatory dues and how they are spent.

- Do No Harm v. Pfizer, No. 1:22-cv-07908 (S.D.N.Y. 2022), aff’d, No. 23-15 (2d Cir. 2023): On September 15, 2022, conservative medical advocacy organization Do No Harm (DNH) filed suit against Pfizer, alleging that Pfizer discriminated against white and Asian students by excluding them from its Breakthrough Fellowship Program. To be eligible for the program, applicants must “[m]eet the program’s goals of increasing the pipeline for Black/African American, Latino/Hispanic and Native Americans.” DNH alleged that the criteria violate Section 1981, Title VI of the Civil Rights Act, the Affordable Care Act, and multiple New York state laws banning racially discriminatory internships, training programs, and employment. In December 2022, the Southern District of New York dismissed the case for lack of subject matter jurisdiction, finding that DNH did not have standing because it did not identify at least one member by name. On March 6, 2024, the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit affirmed the district court’s dismissal, holding that an organization must name at least one affected member to establish Article III standing under the “clear language” of Supreme Court precedent. On March 20, 2024, DNH petitioned the court for a rehearing en banc.

- Latest update: On April 3, 2024, four amicus briefs were filed in support of DNH’s petition for a rehearing en banc. Briefs were filed by: (1) Speech First, an organization “committed to restoring freedom of speech on college campuses,” (2) Pacific Legal Foundation, an organization which “defend[s] individual liberty and limited government,” (3) Young America’s Foundation, which supports “individual freedom, a strong national defense, free enterprise, and traditional values,” The Manhattan Institute, “whose mission is to develop and disseminate new ideas that foster economic choice and individual responsibility,” and Southeastern Legal Foundation, which is “dedicated to defending liberty and Rebuilding the American Republic,” and (4) the American Alliance for Equal Rights, which is “dedicated to challenging distinctions and preferences made on the basis of race and ethnicity.” The four briefs argue that prohibiting anonymity in sensitive cases with “vulnerable plaintiffs” violates the First Amendment and negates the purpose of associational standing in the public interest litigation context.

2. Employment discrimination and related claims:

- Bowen v. City and County of Denver, No. 1:24-cv-00917 (D. Colo. 2024): On April 5, 2024, Joseph Bowen, a sergeant in the Denver Police Department, sued the Department and the City and County of Denver alleging that the Department’s 30×30 initiative, which pledges that 30% of all police recruits will be women by 2030, caused him to lose out on a promotion to captain to three less-qualified women. Bowen alleges that the Department discriminated against him on the basis of his sex, in violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

- Latest update: A scheduling conference is scheduled for June 25, 2024.

- Renault v. Adidas, No. 2024-CP-420-1549 (Court of Common Pleas, South Carolina, April 15, 2024): On April 15, 2024, pro se plaintiff Peter Renault sued Adidas in South Carolina state court for employment discrimination after he was rejected for a supply chain analyst position. Renault alleges that he was qualified but not hired due to the company’s DEI policies.

- Latest update: The docket does not reflect that Adidas has been served.

3. Challenges to agency rules, laws, and regulatory decisions:

- Alliance for Fair Board Recruitment v. SEC, No. 21-60626 (5th Cir. 2021): On October 18, 2023, a unanimous Fifth Circuit panel rejected petitioners’ constitutional and statutory challenges to Nasdaq’s Board Diversity Rules and the SEC’s approval of those rules. Gibson Dunn represents Nasdaq, which intervened to defend its rules. Petitioners sought a rehearing en banc.

- Latest update: On March 21, 2024, petitioners’ briefs were filed. On March 28, 2024, Arizona, Alabama, Alaska, Arkansas, Florida, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Texas, and Utah filed an amicus brief in support of petitioners, arguing that Nasdaq’s rules violate the Equal Protection Clause and states’ rights. Nasdaq and the SEC will file their briefs on April 29, and oral argument is scheduled for May 14.

4. Actions against educational institutions:

- Elliott v. Antioch University, No. 2:24-cv-502 (W.D. Wash.): On April 15, 2024, the plaintiff, a white woman, sued Antioch University for suspending her account after she criticized the school’s decision to have students sign a “civility pledge” committing to anti-racism. Elliott made a series of public videos and online posts expressing her criticisms of the policy changes at Antioch and alleges that when she refused to sign the civility pledge, she was excluded from courses necessary for her to graduate with her degree. Elliott sued Antioch under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act, breach of contract, and defamation.

- Latest update: The docket does not reflect that Antioch University has been served.

Gibson Dunn’s lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding these developments. Please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, any member of the firm’s Labor and Employment practice group, or the following practice leaders and authors:

Jason C. Schwartz – Partner & Co-Chair, Labor & Employment Group

Washington, D.C. (+1 202-955-8242, jschwartz@gibsondunn.com)

Katherine V.A. Smith – Partner & Co-Chair, Labor & Employment Group

Los Angeles (+1 213-229-7107, ksmith@gibsondunn.com)

Mylan L. Denerstein – Partner & Co-Chair, Public Policy Group

New York (+1 212-351-3850, mdenerstein@gibsondunn.com)

Zakiyyah T. Salim-Williams – Partner & Chief Diversity Officer

Washington, D.C. (+1 202-955-8503, zswilliams@gibsondunn.com)

Molly T. Senger – Partner, Labor & Employment Group

Washington, D.C. (+1 202-955-8571, msenger@gibsondunn.com)

Blaine H. Evanson – Partner, Appellate & Constitutional Law Group

Orange County (+1 949-451-3805, bevanson@gibsondunn.com)

© 2024 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP. All rights reserved. For contact and other information, please visit us at www.gibsondunn.com.

Attorney Advertising: These materials were prepared for general informational purposes only based on information available at the time of publication and are not intended as, do not constitute, and should not be relied upon as, legal advice or a legal opinion on any specific facts or circumstances. Gibson Dunn (and its affiliates, attorneys, and employees) shall not have any liability in connection with any use of these materials. The sharing of these materials does not establish an attorney-client relationship with the recipient and should not be relied upon as an alternative for advice from qualified counsel. Please note that facts and circumstances may vary, and prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome.

From the Derivatives Practice Group: The Bank of Israel announced that it will cease publication of Telbor next year and four new directors joined ISDA’s board this week.

New Developments

- Chairman Behnam Announces CFTC’s First DEIA Strategic Plan. On April 18, CFTC Chairman Rostin Behnam announced the agency’s first Strategic Plan to Advance Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility (DEIA Plan). Chairman Behnam said that the two-year DEIA Plan represents a critical step forward in aligning the CFTC with a collective DEIA vision that not only provides genuine support for team members, but also ensures the CFTC is a source of future leaders. The CFTC designed the DEIA Plan to align with its 2022-2026 Strategic Plan and to focus on the following six goals: Inclusive Workplaces, Partnerships and Recruitment, Paid Internships, Professional Development and Advancement, Data, and Equity in Procurement and Customer Education and Outreach. Each goal includes objectives and strategies/actions to achieve the goal, and identifies the agency division(s)/office(s) that will lead and contribute to the implementation of the goal. The CFTC said that an internal DEIA Executive Council will support and guide the implementation of the DEIA Plan. [NEW]

- CFTC Appoints Christopher Skinner as Inspector General. On April 10, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission announced that Christopher L. Skinner has been appointed CFTC’s Inspector General (IG). The CFTC stated that Mr. Skinner brings 15 years of IG experience, including leading and managing Offices of Inspector’s General (OIG), and conducting investigations, inspections, and audits. Mr. Skinner comes to the CFTC from the Federal Election Commission (FEC) where he served as IG since 2019.

New Developments Outside the U.S.

- Telbor Committee to Permanently Cease Publication of Telbor. On April 16, the Telbor Committee of the Bank of Israel decided that the publication of all tenor of Telbor will permanently cease following a final publication on June 30, 2025. The announcement constitutes an “Index Cessation Event” under the 2021 ISDA Interest Rate Derivatives Definitions and the November 2022 Benchmark Module of the ISDA 2021 Fallbacks Protocol. In February 2022, the Telbor Committee decided that the SHIR (Shekel overnight Interest Rate) rate would eventually replace the Telbor interest rate in shekel interest rate derivative transactions. The Bank of Israel said that the decision to switch to the SHIR rate is in accordance with the decisions reached in major economies worldwide, according to which IBOR type interest rates will be replaced by risk-free overnight interest rates. ISDA published cessation guidance for parties affected by the announcement. [NEW]

- New Report Sheds Light on Quality and Use of Regulatory Data Across EU. On April 11, ESMA published the fourth edition of its Report on the Quality and Use of Data aiming to provide transparency on how the data collected under different regulations is used systematically by authorities in the EU, and clarifying the actions taken to ensure data quality. The report provides details on how National Competent Authorities, the European Central Bank, the European Systemic Risk Board and ESMA use the data that is collected through the year from different legislation requirements, including datasets from European Market Infrastructure Regulation, Securities Financing Transactions Regulation, Markets in Financial Instruments Directive, Securitization Regulation, Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive and Money Market Funds Regulation.

New Industry-Led Developments

- Four Directors Join ISDA Board. On April 18, ISDA announced that four directors have joined its Board, three directors were re-appointed, and 10 others have been re-elected at ISDA’s Annual General Meeting in Tokyo. The new directors are: Erik Tim Mueller, Chief Executive Officer, Eurex Clearing AG; Jared Noering, Managing Director, Head of Fixed Income Trading, NatWest Markets; Brad Tully, Managing Director and Global Head of Corporate Derivatives and Private Side Sales for J.P. Morgan; and Jan Mark van Mill, Managing Director of Multi Asset, APG Asset Management. [NEW]

- ISDA Future Leaders in Derivatives Publishes Generative Artificial Intelligence Whitepaper. On April 17, ISDA published a whitepaper from ISDA Future Leaders in Derivatives (IFLD), its professional development program for emerging leaders in the derivatives market. The whitepaper, GenAI in the Derivatives Market: a Future Perspective, was developed by the third cohort of IFLD participants, who began working together in October 2023. According to ISDA, the 38 individuals in the group represent buy- and sell-side institutions, law firms, and service providers from around the world. After being selected for the IFLD program, they were asked to engage with stakeholders, develop positions, and produce a whitepaper on the potential use of generative artificial intelligence (genAI) in the over-the-counter derivatives market. The participants were also given access to ISDA’s training materials, resources, and staff expertise to support the project and their own professional development. ISDA said that, drawing on industry expertise and academic research, the whitepaper identifies a range of potential use cases for genAI in the derivatives market, including document creation, market insight, and risk profiling. ISDA also indicated that it explores regulatory issues in key jurisdictions and addresses the challenges and risks associated with the use of genAI. The paper concludes with a set of recommendations for stakeholders, including investing in talent development, fostering collaboration and knowledge sharing with technology providers, prioritizing ethical AI principles and engaging with policymakers to promote an appropriate regulatory framework. [NEW]

- ISDA Publishes Research Paper on Interest Rate Derivatives, Benchmark Rates and Development Financial Markets in EMDEs. On April 17, ISDA published a research paper in which it outlines the role of interest rate derivatives (IRDs) in supporting the development of financial markets in emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs). It also examines the significance of reliable, robust interest rate (IR) benchmarks. ISDA indicated that the paper draws valuable lessons from the transition from LIBOR to overnight risk-free rates in advanced economies and applies those insights to the context of EMDEs. Through case studies, ISDA attempts to show how various EMDE jurisdictions have successfully adopted and implemented more robust and transparent IR benchmarks. [NEW]

- ISDA Extends Digital Regulatory Reporting Initiative to New Jurisdictions. On April 17, ISDA announced that it is extending its Digital Regulatory Reporting (DRR) initiative to several additional jurisdictions in an effort to enable firms to implement changes to regulatory reporting requirements. The DRR is being extended to cover rule amendments being implemented under the UK European Market Infrastructure Regulation and by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission and the Monetary Authority of Singapore. Those rule changes are due to be implemented in the UK on September 30, 2024, and October 21, 2024 in Australia and Singapore. The DRR code for all three sets of rules is currently available for market participants to review and test. ISDA said that the DRR will be further extended to cover rule changes in Canada and Hong Kong, both due in 2025, and the DRR for the CFTC rules will also be updated to include further anticipated updates, currently under consultation at the commission. Firms can either use the DRR as the basis for implementation or to validate an independent interpretation of the rules. [NEW]

- ISDA Publishes Margin Survey. On April 16, ISDA published its latest margin survey, which shows that $1.4 trillion of initial margin (IM) and variation margin (VM) was collected by 32 leading derivatives market participants for their non-cleared derivatives exposures at the end of 2023, unchanged from the previous year. The survey also reports the amount of IM posted by all market participants to major central counterparties. [NEW]

- ISDA Establishes Suggested Operational Practices for EMIR Refit. On April 16, through a series of discussions held within the ISDA Data and Reporting EMEA Working Group, market participants established and agreed to Suggested Operational Practices (SOP) for over-the-counter derivative reporting in preparation for the commencement of the EMIR Refit regulatory reporting rules on April 29. ISDA said that the SOP matrix was established based on the EMIR Refit validation table, (as published by ESMA), which contains the Regulatory Technical Standards (RTS), the Implementation Technical Standards (ITS) and validation rules. Additional tabs have been added to supplement to SOPs, including product-level SOPs for several of the underlier fields, and listing names of floating rate options. There are also tabs to reflect updates made to the matrix (‘Updates’) and a tab to track questions raised by the ISDA Data and Reporting EMEA Working Group (‘WG Questions’). ISDA indicated that the document will continue to be reviewed and updated as and when required. While the intention of these SOPs is to provide an agreed and standardized market guide for firms to utilize, no firm is legally bound or compelled in any way to follow any determinations made within these EMIR SOPs. [NEW]

- ISDA and IIF Respond to BCBS-CPMI-IOSCO Consultation on Margin Transparency. On April 12, ISDA and the Institute of International Finance (IIF) submitted a response to the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS), Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures (CPMI) and International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) consultation on transparency and responsiveness of initial margin in centrally cleared markets. In their response, the associations expressed support for enhancing transparency on cleared margin for all market participants, which they expect will help with liquidity preparedness and increase resilience of the system, noting it should start with central counterparties (CCPs) making fundamental disclosures about their margin models. In this regard, both associations highlight their support in the response to recommendations one through eight. Regarding recommendation nine, the associations indicated that they are supportive of clients having necessary transparency on clearing member (CM) margin requirements. Regarding recommendation 10, the associations said in the response that they are generally supportive of the principle that CCPs should have visibility into the risk profile of their clearing participants but warned that, in their opinion, the information required under recommendation 10 may raise legal, confidentiality, or competition concerns. Finally, the associations noted that they believe further work should be done on the fundamentals of CCP margin models, for example on the appropriateness of margin periods of risk and the calibration of anti-procyclicality tools, to ensure that margins do not fall too low during low volatility periods. [NEW]

- IOSCO Publishes Updated Workplan. On April 12, IOSCO published its updated 2024 Workplan, which directly supports its overall two-year Work Program published on April 5, 2023. The 2024 Workplan announced new workstreams, reflecting increased focus on AI, tokenization and credit default swaps, and additional work on transition plans and green finance. The 2024 Workplan set out priorities under five themes: Protecting Investors, Address New Risks in Sustainability and Fintech, Strengthening Financial Resilience, Supporting Market Effectiveness and Promoting Regulatory Cooperation and Effectiveness. [NEW]

- ISDA, AIMA, GFXD Publish Paper on Transition to UPI. On April 9, ISDA, the Alternative Investment Management Association (AIMA) and the Global Foreign Exchange Division (GFXD) of the Global Financial Markets Association published a paper on the transition to unique product identifiers (UPI) as the basis for over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives identification across the Markets in Financial Instruments Regulation (MIFIR) regimes. The paper has been sent to the European Commission, which is working on legislation to address appropriate identification of OTC derivatives under MiFIR.

- ISDA Submits Addendum to US Basel III NPR Comment Letter. On April 8, ISDA submitted an addendum to the joint US Basel III ‘endgame’ notice of proposed rulemaking response along with the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association. The addendum contains a more developed proposal for the index bucketing approach for equity investment in funds and an update to the Fundamental Review of the Trading Book Standardized Approach Quantitative Impact Study numbers. [NEW]

- IOSCO Seeks Feedback on the Evolution of Market Structures and Proposed Good Practices. On April 4, the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) published a consultation report on Evolution in the Operation, Governance and Business Models of Exchanges: Regulatory Implications and Good Practices. The consultation report analyzes the structural and organizational changes within exchanges, focusing on business models and ownership structures. It highlights a shift towards more competitive, cross-border, and diversified operations as exchanges integrate into larger corporate groups. The consultation report discusses regulatory considerations, particularly in the organization of individual exchanges and exchange groups and the supervision of multinational exchange groups. It addresses potential conflicts of interest arising from matrix structures and the challenges of overseeing individual exchanges within exchange groups. Additionally, it outlines a set of six proposed good practices for regulators to consider in the supervision of exchanges, particularly when they provide multiple services and/or are part of an exchange group. The good practices are also complemented by a non-exclusive list of supervisory tools used by IOSCO jurisdictions to address the issues under discussion, in the form of “toolkits”. While the Consultation Report focuses on equities listing trading venues, the findings are also relevant to other trading venues, including non-listing trading venues and derivatives trading venues. IOSCO is seeking input from market participants on the major trends and risks observed, and the proposed good practices on or before July 3, 2024.

- ISDA Submits Response to CFTC Proposed Operational Resilience Rules. On April 1, ISDA submitted comments on the CFTC’s notice of proposed rulemaking on requirements to establish an Operational Resilience Framework for Futures Commission Merchants, Swap Dealers and Major Swap Participants, which was published in the Federal Register on January 24, 2024. ISDA recommended that the CFTC adjust adjust portions of the proposed rules relating to governance, third-party relationships, incident notification and implementation period.

The following Gibson Dunn attorneys assisted in preparing this update: Jeffrey Steiner, Adam Lapidus, Marc Aaron Takagaki, Hayden McGovern, and Karin Thrasher.

Gibson Dunn’s lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding these developments. Please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, any member of the firm’s Derivatives practice group, or the following practice leaders and authors:

Jeffrey L. Steiner, Washington, D.C. (202.887.3632, jsteiner@gibsondunn.com)

Michael D. Bopp, Washington, D.C. (202.955.8256, mbopp@gibsondunn.com)

Michelle M. Kirschner, London (+44 (0)20 7071.4212, mkirschner@gibsondunn.com)

Darius Mehraban, New York (212.351.2428, dmehraban@gibsondunn.com)

Jason J. Cabral, New York (212.351.6267, jcabral@gibsondunn.com)

Adam Lapidus – New York (+1 212.351.3869, alapidus@gibsondunn.com)

Stephanie L. Brooker, Washington, D.C. (202.887.3502, sbrooker@gibsondunn.com)

Roscoe Jones Jr., Washington, D.C. (202.887.3530, rjones@gibsondunn.com)

William R. Hallatt, Hong Kong (+852 2214 3836, whallatt@gibsondunn.com)

David P. Burns, Washington, D.C. (202.887.3786, dburns@gibsondunn.com)

Marc Aaron Takagaki, New York (212.351.4028, mtakagaki@gibsondunn.com)

Hayden K. McGovern, Dallas (214.698.3142, hmcgovern@gibsondunn.com)

Karin Thrasher, Washington, D.C. (202.887.3712, kthrasher@gibsondunn.com)

© 2024 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP. All rights reserved. For contact and other information, please visit us at www.gibsondunn.com.

Attorney Advertising: These materials were prepared for general informational purposes only based on information available at the time of publication and are not intended as, do not constitute, and should not be relied upon as, legal advice or a legal opinion on any specific facts or circumstances. Gibson Dunn (and its affiliates, attorneys, and employees) shall not have any liability in connection with any use of these materials. The sharing of these materials does not establish an attorney-client relationship with the recipient and should not be relied upon as an alternative for advice from qualified counsel. Please note that facts and circumstances may vary, and prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome.

We are pleased to provide you with Gibson Dunn’s Accounting Firm Quarterly Update for Q1 2024. The Update is available in .pdf format at the below link, and addresses news on the following topics that we hope are of interest to you:

- SEC Voluntarily Stays Climate-Disclosure Rules Pending Appellate Review

- PCAOB Issues Proposed Rule on Firm Metric Reporting

- SolarWinds Moves to Dismiss SEC Amended Complaint

- Alabama Federal Court Declares Corporate Transparency Act Unconstitutional

- SEC Adopts Final Rules Relating to SPACs

- House Oversight Committee Examines PCAOB Treatment of China-Based Firms

- PCAOB Proposes New Rule on False or Misleading Statements Concerning PCAOB Registration and Oversight

- PCAOB Reopens Comment Period and Holds Roundtable on NOCLAR Proposal

- NCLA Sues PCAOB Claiming Unconstitutional Disciplinary Proceedings

- SEC Commissioner Speaks on Materiality and Engagement with the SEC

- Illinois Appellate Court Issues Verein Ruling in Legal Malpractice Case

- Southern District Rules That PCAOB Inspection Information Is Not “Property”

- Other Recent SEC and PCAOB Enforcement and Regulatory Developments

Please let us know if there are topics that you would be interested in seeing covered in future editions of the Update.

Warmest regards,

Jim Farrell

Monica Loseman

Michael Scanlon

Chairs, Accounting Firm Advisory and Defense Practice Group, Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP

In addition to the practice group chairs, this update was prepared by David Ware, Timothy Zimmerman, Benjamin Belair, Adrienne Tarver, and Monica Limeng Woolley.

Accounting Firm Advisory and Defense Group:

James J. Farrell – Co-Chair, New York (+1 212-351-5326, jfarrell@gibsondunn.com)

Monica K. Loseman – Co-Chair, Denver (+1 303-298-5784, mloseman@gibsondunn.com)

Michael Scanlon – Co-Chair, Washington, D.C.(+1 202-887-3668, mscanlon@gibsondunn.com)

© 2023 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP. All rights reserved. For contact and other information, please visit us at www.gibsondunn.com.

Attorney Advertising: These materials were prepared for general informational purposes only based on information available at the time of publication and are not intended as, do not constitute, and should not be relied upon as, legal advice or a legal opinion on any specific facts or circumstances. Gibson Dunn (and its affiliates, attorneys, and employees) shall not have any liability in connection with any use of these materials. The sharing of these materials does not establish an attorney-client relationship with the recipient and should not be relied upon as an alternative for advice from qualified counsel. Please note that facts and circumstances may vary, and prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome.

On April 15, 2024, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (“EEOC”) issued regulations implementing the Pregnant Workers Fairness Act (“PWFA”). The final rule comes after considering extensive comments on the August 2023 draft rulemaking, and will go into effect on June 18, 2024.

The PWFA was signed into law on December 29, 2022. It was intended to fill gaps in the federal and state legal landscape regarding protections for employees affected by pregnancy, childbirth, or related medical conditions. Specifically, the PWFA requires most employers with 15 or more employees to provide reasonable accommodations for a qualified employee’s or applicant’s known limitations related to, affected by, or arising out of pregnancy, childbirth, or related medical conditions, unless the accommodation will cause an undue hardship on the operation of the employer’s business. The requirements apply even when the medical limitations giving rise to the need for an accommodation would not constitute a disability under the Americans with Disabilities Act (“ADA”). (For a detailed analysis of the PWFA’s requirements and differences between the PWFA and existing federal and state law with respect to the accommodation of pregnancy-related medical restrictions, please see our prior alert.)

The PWFA has been in effect since June 27, 2023, but the final rule and accompanying guidance clarify (and in some ways expand) the obligations that were explicit in the statute itself. Below are 10 key takeaways for employers.

10 Key Takeaways for Employers

- Certain Identified Accommodations Are Assumed To Be Reasonable: The final rule specifies that the following four pregnancy accommodations are reasonable and should be granted in almost every circumstance without documentation: (1) additional restroom breaks, (2) food and drink breaks, (3) allowing water and other drinks to be kept nearby, and (4) allowing sitting or standing, as necessary. Other possible reasonable accommodations specified by the final rule, although not presumptively required, include job restructuring, modifying work schedules, use of paid leave, and reassignment to a vacant position.

- Broad Scope of Covered Conditions: The EEOC’s “non-exhaustive list” of conditions that can give rise to a request for accommodation under the PWFA include: current pregnancy, past pregnancy, lactation (including breastfeeding and pumping), use of birth control, menstruation, postpartum depression, gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, infertility and fertility treatments, endometriosis, miscarriage, stillbirth, and having or choosing not to have an abortion, among other conditions. The breadth of this list has drawn criticism for exceeding the EEOC’s authority—including a public dissent from EEOC Commissioner Andrea Lucas—and the abortion-related aspect in particular has attracted strong attention (and is likely to be litigated).

- Applicants/Employees May Need To Be Excused From Essential Functions For Extended Periods: Under the ADA, only a “qualified individual” is entitled to a reasonable accommodation, and a qualified individual is one who can perform the essential functions of the job with or without a reasonable accommodation. By contrast, under the PWFA, an individual is still qualified—and therefore entitled to a reasonable accommodation—even if they cannot perform an essential function of the job now, so long as the limitation is for “a temporary period” and the essential function can be performed in the “near future.”

- Employers Cannot Seek Documentation For Certain Requests: The final rule generally prohibits employers from seeking documentation in many circumstances, including: (1) when the limitation and need for a reasonable accommodation is obvious; (2) when the employer already has sufficient information to support a known limitation related to pregnancy; (3) when the request is for one of the four identified reasonable accommodations listed above (i.e., additional restroom breaks; food/drink breaks; beverages near the work station; and sitting or standing as needed); (4) when the request is for a lactation accommodation; and (5) when the accommodation is available without documentation for other employees seeking the same accommodation for non-PWFA reasons.

- Informal Requests Can Trigger Statutory Obligations: The guidance accompanying the final rule indicates that verbal conversations with direct supervisors can trigger accommodation obligations, and an employee’s failure to fill out paperwork or speak to the “right” supervisor or designated department is not grounds for either delaying or not providing the accommodation. In other words, the initial request (or statement of need for an accommodation) alone may be sufficient to place the employer on notice and trigger the interactive accommodation process.

- Account For Accommodations In Reporting And Metrics: Where a reasonable accommodation is granted (e.g., extra bathroom or water breaks), employers should ensure that technologies are appropriately adjusted to integrate the accommodation. Given that employers are increasingly using technology in the workplace for purposes such as monitoring attendance or tracking productivity and performance, it is important that employers develop policies that contemplate how a reasonable accommodation might impact the accuracy of these tools. For example, the EEOC suggests that calculations on productivity for a given shift may need to be adjusted to account for the additional excused break periods.

- Act With Expediency And Consider Interim Accommodations: Although the PWFA’s interactive process largely tracks that of the ADA, the final rule provides that employers must respond to requests under the PWFA with “expediency” and notes that granting an interim accommodation will decrease the likelihood that an unnecessary delay will be found.

- Unpaid Leave As A Last Resort: As the PWFA itself makes clear, employers may only require an employee to take leave as a last resort if there are no other reasonable accommodations that can be provided absent undue hardship. The final rule and guidance continue this theme, underscoring that requiring an employee to take unpaid leave or to use their leave after they ask for an accommodation and are awaiting a response could also violate the PWFA if, for example, there is paid work that the employee could have been provided during the interactive process.

- Overlap With The ADA: Overlap With The ADA: The final rule acknowledges that there may be circumstances in which a qualified individual may be entitled to an accommodation under either the PWFA or the ADA for a pregnancy-related limitation. The interpretive guidance emphasizes that employees are not required to identify the statute under which they are requesting a reasonable accommodation, so employers should train human resources and management professionals to identify and apply the applicable framework.

- Don’t Forget About Applicants: The PWFA prohibits employers from refusing to hire a pregnant applicant because they assume that the applicant will soon need to leave to recover for childbirth. In addition, the interpretive guidance flags that the accommodation process is often more difficult to navigate for applicants than for existing employees. As such, employers should consider training recruiting and onboarding professionals on how to best ensure that an applicant understands the process for requesting a reasonable accommodation during the hiring process. The guidance notes that an applicant may not know enough about, for example, the equipment used by the employer or the application process itself to request an accommodation and the employer may likewise not have enough information to suggest an appropriate accommodation. Accordingly, employers might consider trying to anticipate potential hurdles to accessibility during the hiring process and either remedy the obstacles, if feasible, or provide advanced notice during the early stages of the process so that the applicant can identify any potential issues and request a reasonable accommodation.

Gibson Dunn’s lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding these developments. To learn more about these issues, please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, any member of the firm’s Labor and Employment practice group, or the following authors and practice leaders:

Molly T. Senger – Partner, Labor & Employment

Washington, D.C. (+1 202.955.8571, msenger@gibsondunn.com)

Jason C. Schwartz – Partner & Co-Chair, Labor & Employment

Washington, D.C. (+1 202.955.8242, jschwartz@gibsondunn.com)

Katherine V.A. Smith – Partner & Co-Chair, Labor & Employment

Los Angeles (+1 213.229.7107, ksmith@gibsondunn.com)

© 2024 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP. All rights reserved. For contact and other information, please visit us at www.gibsondunn.com.

Attorney Advertising: These materials were prepared for general informational purposes only based on information available at the time of publication and are not intended as, do not constitute, and should not be relied upon as, legal advice or a legal opinion on any specific facts or circumstances. Gibson Dunn (and its affiliates, attorneys, and employees) shall not have any liability in connection with any use of these materials. The sharing of these materials does not establish an attorney-client relationship with the recipient and should not be relied upon as an alternative for advice from qualified counsel. Please note that facts and circumstances may vary, and prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome.

Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP has appointed Mark Leverkus as Of Counsel in its Global Finance and Transportation and Space Practice Groups in London.

Mark is recognised by The Legal 500 Rankings in Finance: Transport Finance and Leasing, and has been named a “Rising Star” by Airfinance Journal. He was previously a senior associate in the transportation and space group of Milbank, and he has also been seconded to the legal department of a major UK bank, and to a regional aircraft lessor in Dublin.

Madalyn Miller, Co-chair of the Transportation and Space Group and Partner in the Global Finance Group at Gibson Dunn, said: “Mark’s experience on some of the largest and most complex aviation and space matters make him a great addition to the team and we’re pleased to welcome him to the firm. We are continuing to expand our Global Finance and Transportation and Space Groups and the London office is particularly important as we grow.”

Mark’s hire follows a period of growth for the firm’s Global Finance Practice Group, with other recent arrivals including partners David Irvine, Trinh Chubbock, Kavita Davis and Ben Shorten in London, Jin Hee Kim and Doug Horowitz in New York, Chad Nichols in Houston/New York, Frederick Lee in Dallas, and Darko Adamovic in Paris.

About Mark Leverkus

Mark is an Of Counsel in the London office of Gibson Dunn & Crutcher, and is a member of the firm’s Transportation and Space and Global Finance practice groups. His deals have won numerous awards from transport industry publications and ratings services, and include acting for financiers, arrangers, equity investors, leasing companies, export credit agencies and operators on a range of sophisticated financing, leasing and sale and purchase transactions, involving aircraft, satellites and other moveable equipment. He also has extensive experience in the trading and repackaging of such transactions, as well as in restructurings, disputes, work-outs and repossessions.

About the Gibson Dunn Transportation and Space Practice Group

The Transportation and Space Practice Group serves some of the largest aerospace, defence and satellite companies in the world as well as cutting-edge emerging technology businesses, and the private equity and financial institutions that support and enable their growth. Our aerospace and related technologies lawyers have a wide cross-section market knowledge and offer a strong and longstanding track record serving the traditional aerospace industry and supporting clients in various new and emerging technologies and markets.

About the Gibson Dunn Global Finance Practice Group

The Global Finance Practice Group serves clients around the world, including private equity sponsors, corporate borrowers, major financial institutions, and hedge funds. It includes more than 85 lawyers in our offices worldwide, advising on a broad array of financing transactions. The group works closely with mergers and acquisitions colleagues on acquisition financings and with the firm’s capital markets team. The group also draws extensively on the knowledge and skills of other specialist practice areas, such as environmental, tax, employee benefits, and litigation.

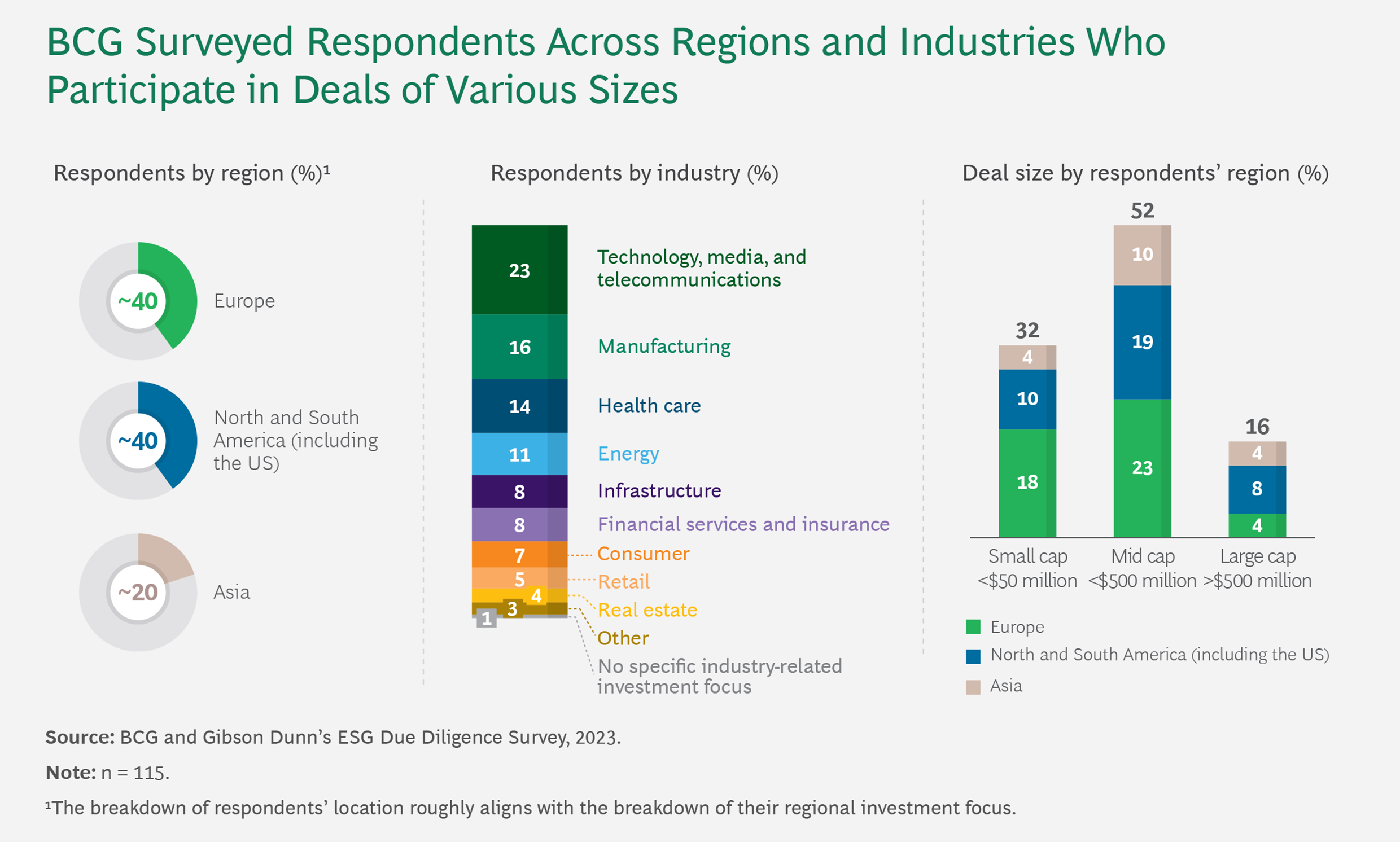

A recent global survey of dealmakers by BCG and Gibson Dunn reveals a striking consensus: conducting environmental, social, and governance (ESG) due diligence is now indispensable for M&A transactions.