On August 20, 2021, the Standing Committee of China’s National People’s Congress passed the Personal Information Protection Law (“PIPL”), which will take effect on November 1, 2021. We previously reported on this development here, when the law was in draft form. An unofficial translation of the newly enacted PIPL is available here and the Mandarin version of the PIPL is available here.[1]

The PIPL applies to “personal information processing entities (“PIPEs”),” defined as “an organisation or individual that independently determines the purposes and means for processing of personal information.” (Article 73). The PIPL defines “personal information” broadly as “various types of electronic or otherwise recorded information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person,” excluding anonymized information, and defines “processing” as “the collection, storage, use, refining, transmission, provision, public disclosure or deletion of personal information.” (Article 4).

The PIPL shares many similarities with the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (the “GDPR”), including its extraterritorial reach, restrictions on data transfer, compliance obligations and sanctions for non-compliance, amongst others. The PIPL raises some concerns for companies that conduct business in China, even where such companies’ data processing activities take place outside of China, and the consequences for failing to comply could potentially include monetary penalties and companies being placed on a government blacklist.

Below, we describe the companies subject to the PIPL, key features of the PIPL, and highlight critical issues for companies operating in China in light of this important legislative development.

I. Which Companies are Subject to PIPL?

- The PIPL applies to cross-border transmission of personal information and applies extraterritorially. Where PIPEs transmit personal information to entities outside China, they must inform the data subjects of the transfer, obtain their specific consent to the transfer, and ensure that the data recipients satisfy standards of personal information protection similar to those in the PIPL.The PIPL applies to organisations operating in China, as well as to foreign organisations and individuals processing personal information outside China in any one of the following circumstances: (1) the organisation collects and processes personal data for the purpose of providing products or services to natural persons in China; (2) the data will be used in analysing and evaluating the behaviour of natural persons in China; or (3) under other unspecified “circumstances stipulated by laws and administrative regulations” (Article 3). This is an important similarity between the PIPL and GDPR, as the GDPR’s data protection obligations apply to non-EU data controllers and processors that track, analyze and handle data from visitors within the EU. Similarly, under the PIPL, a foreign receiving party must comply with the PIPL’s standard of personal information protection if it handles personal information from natural persons located in China.

- The PIPL gives the Chinese government broad authority in processing personal information. State organisations may process personal information to fulfil statutory duties, but may not process the data in a way that exceeds the scope necessary to fulfil these statutory duties (Article 34). Personal information processed by state organisations must be stored within China (Article 36).

II. Key Features of PIPL

- The PIPL establishes guiding principles on protection of personal information. According to the PIPL, processing of personal information should have a “clear and reasonable purpose” and should be directly related to that purpose (Article 6). The PIPL requires that the collection of personal information be minimized and not excessive (Article 6), and requires PIPEs to ensure the security of personal information (Articles 8-9). To that end, the PIPL imposes a number of compliance obligations on PIPEs, including requiring PIPEs to establish policies and procedures on personal information protection, implement technological solutions to ensure data security, and carry out risk assessments prior to engaging in certain processing activities (Articles 51 – 59).

- The PIPL adopts a risk-based approach, imposing heightened compliance obligations in specified high-risk scenarios. For instance, PIPEs whose processing volume exceeds a yet-to-be-specified threshold must designate a personal information protection officer responsible for supervising the processing of personal data (Article 52). PIPEs operating “internet platforms” that have a “very large” number of users must engage an external, independent entity to monitor compliance with personal information protection obligations, and regularly publish “social responsibility reports” on the status of their personal information protection efforts (Article 58).The law mandates additional protections for “sensitive personal information,” broadly defined as personal information that, once disclosed or used in an illegal manner, could infringe on the personal dignity of natural persons or harm persons or property (Article 28). “Sensitive personal information” includes biometrics, religious information, special status, medical information, financial account, location information, and personal information of minors under the age of 14 (Article 28). When processing “sensitive personal information,” according to the PIPL, PIPEs must only use information necessary to achieve the specified purpose of the collection, adopt strict protective measures, and obtain the data subjects’ specific consent (Article 28-29).

- The PIPL creates legal rights for data subjects. According to the new law, PIPEs may process personal information only after obtaining fully informed consent in a voluntary and explicit statement, although the law does not provide additional details regarding the required format of this consent. The law also sets forth certain situations where obtaining consent is unnecessary, including where necessary to fulfil statutory duties and responsibilities or statutory obligations, or when handling personal information within a reasonable scope to implement news reporting, public opinion supervision and other such activities for the public interest (Articles 13-14, 17). Where consent is required, PIPEs should obtain a new consent where it changes the purpose or method of personal information processing after the initial collection (Article 14). The law also requires PIPEs to provide a convenient way for individuals to withdraw their consent (Article 15), and mandates that PIPEs keep the personal information only for the shortest period of time necessary to achieve the original purpose of the collection (Article 19).If PIPEs use computer algorithms to engage in “automated decision making” based on individuals’ data, the PIPEs are required to be transparent and fair in the decision making, and are prohibited from using automated decision making to engaging in “unreasonably discriminatory” pricing practices (Article 24, 73). “Automated decision-making” is defined as the activity of using computer programs to automatically analyze or assess personal behaviours, habits, interests, or hobbies, or financial, health, credit, or other status, and make decisions based thereupon (Article 73(2)).When individuals’ rights are significantly impacted by PIPEs’ automated decision making, individuals can demand PIPEs to explain the decision making and decline automated decision making (Article 24).

III. Potential Issues for Companies Operating in China

The passage of the PIPL and the uncertainty surrounding many aspects of the law creates a number of potential issues and concerns for companies operating in China. These include the following:

- Foreign organisations may be subject to the PIPL’s regulatory requirements. The PIPL applies to data processing activities, even where those activities take place outside of China, provided they are carried out for the purpose of conducting business in China or evaluating individuals’ behavior in the country. The law is currently silent on how close the nexus must be between the data processing and Chinese business activities. The law also mandates that data processing activities taking place outside of China are subject to the PIPL under “other circumstances stipulated by laws and administrative regulations.” At present there is no guidance as to what these circumstances will be.Foreign organisations subject to the PIPL will need to comply with requirements including security assessments, assigning local representatives to oversee data processing, and reporting to supervisory agencies in China, though the exact parameters of these requirements remain unclear (Articles 51–58).

- The PIPL creates penalties for organisations that fail to fulfil their obligations to protect personal information (Article 66). These penalties include disgorgement of profits and provisional suspension or termination of electronic applications used by PIPEs to conduct the unlawful collection or processing. Companies and individuals may be subject to a fine of not more than 1 million RMB (approximately $154,378.20) where they fail to remediate conduct found to be in violation of the PIPL, with responsible individuals subject to fines of 10,000 to 100,000 RMB (approximately $1,543.81 to $15,438.05).Companies and responsible individuals face particularly stringent penalties where the violations are “grave,” a term left undefined in the statute. In these cases, the PIPL allows for fines of up to 50 million RMB (approximately $7,719,027.00) or 5% of annual revenue, although the PIPL does not specify which parameter serves as the upper limit for the fines. Authorities may also suspend the offending business activities, stop all business activities entirely, or cancel all administrative or business licenses. Individuals responsible for “grave” violations may be fined between 100,000 and 1 million RMB (approximately $15,438.29 to $154,382.93), and may also be prohibited from holding certain job titles, including Director, Supervisor, high-level Manager or Personal Information Protection Officer, for a period of time. In contrast, fines for severe violations of the GDPR can be up to €20 million (approximately $23,486,300.00) or up to 4% of the undertaking’s total global turnover of the preceding fiscal year (whichever is higher).

- Foreign organisations may also be subject to consequences under the PIPL for violating Chinese citizens’ personal information rights or harming China’s national security or public interest. The state cybersecurity and informatization department may place offending organisations on a blacklist, resulting in restrictions on receiving personal information for blacklisted entities (Article 42). The PIPL does not provide clarity on what constitutes a violation of Chinese citizens’ personal information rights or what qualifies as harming China’s national security or public interest.

Companies operating in China should pay particular attention to the cross-border data transfer issues raised by the PIPL:

- Foreign organisations will need to disclose certain information when transferring personal information outside of China’s borders. Under the PIPL, PIPEs must obtain the data subject’s consent prior to transfer, although the required form and method of that consent is not clear (Article 39). Entities seeking to transfer data must also provide the data subject with information about the foreign recipient, including its name, contact details, purpose and method of the data processing, the categories of personal information provided and a description of the data subject’s rights under the PIPL (Article 39).

- Certain companies may need to undergo a government security assessment prior to cross-border data transfers. In addition to the consent and disclose requirements under Article 39, “critical information infrastructure operators” and PIPEs processing personal information in quantities exceeding government limits must pass a government security assessment prior to transferring data outside of China (Article 40). The term “critical information infrastructure operator” is not further defined within the PIPL, the term is, however, broadly defined within the newly passed Regulations on the Security and Protection of Critical Information Infrastructure (the “Regulations on Critical Information Infrastructure”), which come into effect on September 1, 2021 (the Mandarin version is available here). Under Article 2 of the Regulations on Critical Information Infrastructure, a “critical information infrastructure operator” is a company engaged in important industries or fields, including public communication and information services, energy, transport, water, finance, public services, e-government services, national defense and any other important network facilities or information systems that may seriously harm national security, the national economy and people’s livelihoods, or public interest in the event of incapacitation, damage or data leaks.The PIPL also does not specify the data thresholds beyond the quantities provided by the state cybersecurity and information department or the nature of the security assessment, nor does it reference any specific legislation issued by the state cybersecurity and informatization department for purposes of determining such data thresholds (Article 40).

- PIPEs outside China that conduct personal data processing activities for the purpose of conducting business in China or evaluating individuals’ behaviour in the country must establish an entity or appoint an individual within China to be responsible for personal information issues. Such foreign organisations must report the name of the relevant entity or the representative’s name and contact method to the departments fulfilling personal information protection duties, although the PIPL does not specify or name to which departments foreign organisations must report in such instances (Article 53).

- Companies and individuals may not provide personal information stored within China to foreign judicial or enforcement agencies, without prior approval of the Chinese government. As summarized in our prior client alert, the PIPL adds to a growing list of laws that restrict the provision of data to foreign judiciaries and government agencies, which could have a far-reaching impact on cross-border litigation and investigations. Chinese authorities will process requests from foreign judicial or enforcement agencies for personal information stored within China in accordance with applicable international treaties or the principle of equality and reciprocity (Article 41). The PIPL does not provide any guidance on how a company should seek approval if it wishes to export personal data in response to a request from a foreign government agency or a foreign court.

IV. Next Steps

The passage of the PIPL comes during a time where China has increased its regulatory scrutiny on technology companies and other entities with large troves of sensitive public information, and their data usage. Given the broad scope of the PIPL and its extraterritorial reach, organisations inside and outside of China will need to review their data protection and transfer strategies to ensure they do not run afoul of this network of legislation.

Even for companies that currently have GDPR compliance programs in place, the PIPL introduces new requirements not currently required under the GDPR. Examples of such requirements unique to the PIPL include, amongst others, establishing a legal entity within China and passing a security review prior to exporting personal data that reaches a certain undisclosed threshold. How the government enforces the statute and interprets its provisions remain to be seen, and a PIPL compliance program will likely require a nuanced understanding of Chinese cultural and business practices.

Companies operating in China should pay close attention to regulations, guidance documents and enforcement actions related to the PIPL as the Chinese government continues to bolster its data protection legal infrastructure, and seek guidance from knowledgeable counsel.

___________________________

[1] Please note that the discussion of Chinese law in this publication is advisory only.

This alert was prepared by Connell O’Neill, Kelly Austin, Oliver Welch, Ning Ning, Felicia Chen, and Jocelyn Shih.

Gibson Dunn lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have about these developments. Please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work in the firm’s Privacy, Cybersecurity and Data Innovation practice group, or the following authors:

Kelly Austin – Hong Kong (+852 2214 3788, kaustin@gibsondunn.com)

Connell O’Neill – Hong Kong (+852 2214 3812, coneill@gibsondunn.com)

Oliver D. Welch – Hong Kong (+852 2214 3716, owelch@gibsondunn.com)

Privacy, Cybersecurity and Data Innovation Group:

Asia

Kelly Austin – Hong Kong (+852 2214 3788, kaustin@gibsondunn.com)

Connell O’Neill – Hong Kong (+852 2214 3812, coneill@gibsondunn.com)

Jai S. Pathak – Singapore (+65 6507 3683, jpathak@gibsondunn.com)

Europe

Ahmed Baladi – Co-Chair, PCDI Practice, Paris (+33 (0)1 56 43 13 00, abaladi@gibsondunn.com)

James A. Cox – London (+44 (0) 20 7071 4250, jacox@gibsondunn.com)

Patrick Doris – London (+44 (0) 20 7071 4276, pdoris@gibsondunn.com)

Kai Gesing – Munich (+49 89 189 33-180, kgesing@gibsondunn.com)

Bernard Grinspan – Paris (+33 (0)1 56 43 13 00, bgrinspan@gibsondunn.com)

Penny Madden – London (+44 (0) 20 7071 4226, pmadden@gibsondunn.com)

Michael Walther – Munich (+49 89 189 33-180, mwalther@gibsondunn.com)

Alejandro Guerrero – Brussels (+32 2 554 7218, aguerrero@gibsondunn.com)

Vera Lukic – Paris (+33 (0)1 56 43 13 00, vlukic@gibsondunn.com)

Sarah Wazen – London (+44 (0) 20 7071 4203, swazen@gibsondunn.com)

United States

Alexander H. Southwell – Co-Chair, PCDI Practice, New York (+1 212-351-3981, asouthwell@gibsondunn.com)

S. Ashlie Beringer – Co-Chair, PCDI Practice, Palo Alto (+1 650-849-5327, aberinger@gibsondunn.com)

Debra Wong Yang – Los Angeles (+1 213-229-7472, dwongyang@gibsondunn.com)

Matthew Benjamin – New York (+1 212-351-4079, mbenjamin@gibsondunn.com)

Ryan T. Bergsieker – Denver (+1 303-298-5774, rbergsieker@gibsondunn.com)

David P. Burns – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3786, dburns@gibsondunn.com)

Nicola T. Hanna – Los Angeles (+1 213-229-7269, nhanna@gibsondunn.com)

Howard S. Hogan – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3640, hhogan@gibsondunn.com)

Robert K. Hur – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3674, rhur@gibsondunn.com)

Joshua A. Jessen – Orange County/Palo Alto (+1 949-451-4114/+1 650-849-5375, jjessen@gibsondunn.com)

Kristin A. Linsley – San Francisco (+1 415-393-8395, klinsley@gibsondunn.com)

H. Mark Lyon – Palo Alto (+1 650-849-5307, mlyon@gibsondunn.com)

Karl G. Nelson – Dallas (+1 214-698-3203, knelson@gibsondunn.com)

Ashley Rogers – Dallas (+1 214-698-3316, arogers@gibsondunn.com)

Deborah L. Stein – Los Angeles (+1 213-229-7164, dstein@gibsondunn.com)

Eric D. Vandevelde – Los Angeles (+1 213-229-7186, evandevelde@gibsondunn.com)

Benjamin B. Wagner – Palo Alto (+1 650-849-5395, bwagner@gibsondunn.com)

Michael Li-Ming Wong – San Francisco/Palo Alto (+1 415-393-8333/+1 650-849-5393, mwong@gibsondunn.com)

Cassandra L. Gaedt-Sheckter – Palo Alto (+1 650-849-5203, cgaedt-sheckter@gibsondunn.com)

© 2021 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP

Attorney Advertising: The enclosed materials have been prepared for general informational purposes only and are not intended as legal advice.

This edition of Gibson Dunn’s Federal Circuit Update summarizes new petitions for certiorari in cases originating in the Federal Circuit concerning the Patent Trial and Appeal Board’s NHK-Fintiv Rule. This Update also discusses recent Federal Circuit decisions. Notably, starting with the September 2021 court sitting, the court has now resumed in-person arguments.

Federal Circuit News

Supreme Court:

The Court did not add any new cases originating at the Federal Circuit.

Noteworthy Petitions for a Writ of Certiorari:

There are two new certiorari petitions currently before the Supreme Court concerning the Patent Trial and Appeal Board’s NHK-Fintiv Rule, under which the Board may deny institution of inter partes review proceedings when the challenged patent is subject to pending district court litigation.

- Apple Inc. v. Optis Cellular Technology, LLC (U.S. No. 21-118): “Whether the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit may review, by appeal or mandamus, a decision of the U.S. Patent & Trademark Office denying a petition for inter partes review of a patent, where review is sought on the grounds that the denial rested on an agency rule that exceeds the PTO’s authority under the Leahy-Smith America Invents Act, is arbitrary or capricious, or was adopted without required notice-and-comment rulemaking.”

- Mylan Laboratories Ltd. v. Janssen Pharmaceuticals, N.V. (U.S. No. 21-202): “Does 35 U.S.C. § 314(d) categorically preclude appeal of all decisions not to institute inter partes review?” 2. “Is the NHK-Fintiv Rule substantively and procedurally unlawful?”

The following petitions are still pending:

- Biogen MA Inc. v. EMD Serono, Inc. (U.S. No. 20-1604) concerning anticipation of method-of-treatment patent claims. Gibson Dunn partner Mark A. Perry is counsel for the respondent.

- American Axle & Manufacturing, Inc. v. Neapco Holdings LLC (U.S. No. 20-891) concerning patent eligibility under 35 U.S.C. § 101, in which the Court has invited the Solicitor General to file a brief expressing the views of the United States.

- PersonalWeb Technologies, LLC v. Patreon, Inc. (U.S. No. 20-1394) concerning the Kessler doctrine.

Upcoming Oral Argument Calendar

The court has now resumed in-person arguments for the September 2021 court sitting.

The list of upcoming arguments at the Federal Circuit is available on the court’s website.

Live streaming audio is available on the Federal Circuit’s new YouTube channel. Connection information is posted on the court’s website.

Key Case Summaries (August 2021)

Qualcomm Incorporated v. Intel Corporation (Fed. Cir. No. 20-1589): Intel petitioned for six inter partes reviews (IPRs) challenging the validity of a patent owned by Qualcomm. During the IPRs, neither party disputed that the challenged claims required signals that increased user bandwidth. The PTAB, however, construed the claims in a way that omitted any requirement that the signals increase bandwidth. Qualcomm appealed the PTAB’s decision and argued that it was not afforded notice and an opportunity to respond to the PTAB’s construction.

The Federal Circuit (Moore, C.J., joined by Reyna, J. and Stoll, J.) vacated and remanded the PTAB’s decisions. Although the PTAB may adopt a different construction from a disputed, proposed construction, the court held that the Board may not adopt a claim construction that diverges from an agreed-upon requirement for a term. Because neither party could have anticipated the PTAB’s deviation, especially where the International Trade Commission had adopted the increased bandwidth requirement, the court held that the Board needed to provide notice and an adequate opportunity to respond. Because all briefing included the increased bandwidth requirement, the court rejected Intel’s argument that Qualcomm was not prejudiced. The court also found that a single question relating to the bandwidth requirement at the PTAB hearing did not provide adequate notice. Finally, the court found that the ability to seek rehearing from the PTAB’s decision was not a substitute for notice and an adequate opportunity to respond.

Personal Web Technologies LLC v. Google LLC (Fed. Cir. No. 20-1543): PersonalWeb sued Google and YouTube (collectively, “Google”) in the Eastern District of Texas, asserting three related patents directed to data-processing systems. After the cases were transferred to the Northern District of California, that district court granted Google’s motion for judgment on the pleadings that the asserted claims were ineligible under 35 U.S.C. § 101.

The panel (Prost, J., joined by Lourie and Reyna, J.J.) affirmed. At step one, the panel agreed with the district court that the asserted claims are directed to a three-step process: “(1) using a content-based identifier generated from a ‘hash or message digest function,’ (2) comparing that content-based identifier against something else, [that is,] another content-based identifier or a request for data; and (3) providing access to, denying access to, or deleting data.” The panel held that this claimed process amounted to the abstract idea of using “an algorithm-generated content-based identifier to perform the claimed data-management functions.” The panel explained that these functions are ineligible mental processes. Pointing to its prior cases, the panel explained that each of the three functions—generating, comparing, and using content-based identifiers to manage data—are concepts the Federal Circuit previously described as abstract. At step two, the Court concluded that the alleged inventive concept—“making inventive use of cryptographic hashes”—is simply a restatement of the abstract idea itself. The panel agreed with the district court that “using a generic hash function, a server system, or a computer does not render these claims non-abstract,” and explained that each of the supposed improvement disclosed in the specification was likewise abstract.

GlaxoSmithKlein LLC v. Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc. (Fed. Cir. No. 18-1976): GlaxoSmithKline (“GSK”) sued Teva in the District of Delaware. After a jury returned a verdict of induced infringement against Teva, the district court granted Teva’s renewed JMOL, holding that Teva could not induce infringement with its “skinny label” because that label carved out the patented use of carvedilol. The district court also held that GSK had failed to prove that Teva caused inducement because it did not show that it was Teva’s actions that actually caused doctors to directly infringe by prescribing generic carvedilol to treat CHF.

The panel majority (Moore, C.J., and Newman, J.) vacated the grant of the JMOL and reinstated the jury’s verdict of induced infringement, with Judge Prost dissenting. Teva petitioned for rehearing, which the panel granted. The panel issued a new decision, in which the same majority once more reinstated the jury’s verdict of induced infringement against Teva. The majority held that whether a carve-out indication instructs a patented use is a question of fact. Considering the evidence in the record, the majority concluded that substantial evidence supported the jury’s determination that Teva induced infringement by not effecting a section viii carve-out because Teva advertised its drug as a generic equivalent and thereby actively encouraged a patented therapeutic use. The majority warned that this was a decision based on a “narrow, case-specific review of substantial evidence,” and agreed with amici that a “generics could not be held liable for merely marketing and selling under a ‘skinny’ label omitting all patented indications, or for merely noting (without mentioning any infringing uses) that FDA had rated a product as therapeutically equivalent to a brand-name drug.”

Judge Prost dissented again, arguing that the majority’s decision weakens the section viii carve-out by creating confusion for generic companies as to when they may face liability. Judge Prost pointed out that GSK expressly told the FDA that only one use was patented, and so Teva carved out that use. Judge Prost also argued that the majority’s decision changes the law of inducement by blurring the line between merely describing an infringing use and actually encouraging, recommending, or promoting an infringing use. Judge Prost explained that unlike direct infringement, induced infringement requires a showing of intent, and argued that no such intent by Teva could be shown because by carving out the patented use, it was actually taking steps to avoid infringement.

Andra Group, LP v. Victoria’s Secret Stores, LLC (Fed. Cir. No. 20-2009): Andra Group sued several related Victoria’s Secret entities in the Eastern District of Texas. Three entities (“Non-Store Defendants”)—corporate parent L Brands, Inc., Victoria’s Secret Direct Brand Management, LLC, and Victoria’s Secret Stores Brand Management, Inc.—do not have any employees, stores, or any other physical presence in the Eastern District of Texas. The fourth entity (“Store Defendant”) operates retail stores in the Eastern District of Texas. The Non-Store Defendants moved to dismiss the infringement suit for improper venue, and the district court granted the motion. Andra Group appealed.

The Federal Circuit (Hughes, J., joined by Reyna, J. and Mayer, J.) affirmed. The court held that the Store Defendant’s retail stores were not a regular and established place of business of the Non-Store Defendants. The court noted that the evidence showed that the Non-Store Defendants did not have the right to direct or control the Store Defendant’s employees. The court also found that the Store Defendant’s acceptance of returns for merchandise purchased on the website (which was run by a Non-Store Defendant) was a discrete task insufficient to establish an agency relationship. The court also rejected Andra’s argument that the Non-Store Defendants ratified the Store Defendant’s retail stores as their own place of business. The court held that a defendant must actually engage in business from that location and simply advertising a place of business is not sufficient to make it a place of business.

Omni MedSci, Inc. v. Apple Inc. (Fed. Cir. No. 20-1715): In a patent infringement suit brought by Omni against Apple, Apple filed a motion to dismiss for lack of standing. Apple contended that the asserted patents were not owned by Omni, but by University of Michigan (“UM”). Dr. Islam, the named inventor, was employed by UM and had signed an employment agreement that stated, inter alia, that intellectual property developed using university resources “shall be the property of the University.” Dr. Islam took a leave of absence during which he filed multiple provisional patent applications, which ultimately issued as the asserted patents. Dr. Islam then assigned these patents to Omni. The district court determined that the provision in Dr. Islam’s employment agreement “was not a present automatic assignment of title, but, at most, a statement of a future intention to assign.” Apple requested the district court grant certification of the standing question to the Federal Circuit, which was granted.

The majority (Linn, J., joined by Chen, J.) affirmed, and agreed that Dr. Islam’s employment agreement did not constitute a present automatic assignment or a promise to assign in the future. The majority found that the agreement did not include language such as “will assign” or “agrees to grant and does hereby grant,” which have been previously held to constitute a present automatic assignment of a future interest. At most, UM’s agreement with phrases such as “shall be the property of the University” and “shall be owned as agreed upon in writing,” was a promise of a potential future assignment, not as a present automatic transfer. The majority also found a lack of present tense words of execution, such as “hereby grants and assigns,” supported its interpretation.

Judge Newman dissented. She reasoned that because the employment agreement necessarily applies only to future inventions, in which future tense is used, the future tense “shall be the property of the University” is appropriate, and should have vested ownership of the patents in the University. Thus, she concluded that Omni did not have standing to bring the infringement suit.

Campbell Soup Company v. Gamon Plus, Inc. (Fed. Cir. No. 20-2344): Gamon sued Campbell Soup and Trinity Manufacturing (together, “Campbell”) for infringing two design patents, the commercial embodiment of which was called the iQ Maximizer. Campbell petitioned for inter partes review on the grounds that Gamon’s patents would have been obvious over another design patent (“Linz”). The Patent Trial and Appeal Board concluded that Campbell failed to prove unpatentability based on Linz, reasoning that although Linz had the same overall visual appearance as the claimed designs, it was outweighed by objective indicia of nonobviousness. The Board presumed a nexus between those objective indicia and the claimed designs because it found that the iQ Maximizer was coextensive with the claims.

Campbell appealed, and the Federal Circuit (Moore, C.J., Prost and Stoll, JJ.) reversed. The Court held that substantial evidence supported the Board’s finding that Linz creates “the same overall visual appearance as the claimed design[s].” However, under the next step of the design patent obviousness analysis, the Court held that the Board failed to answer the question of “whether unclaimed features are ‘insignificant,’” and that “[u]nder the correct legal standard, substantial evidence does not support the Board’s finding of coextensiveness.” The Court wrote, “We do not go so far as to hold that the presumption of nexus can never apply in design patent cases. It is, however, hard to envision a commercial product that lacks any significant functional features such that it could be coextensive with a design patent claim.” Finally, the Court held that Gamon failed to show that the objective indicia are the “direct result of the unique characteristics of the claimed invention,” because, for example, characteristics of the iQ Maximizer that led to commercial success “were not new.”

Venue in the Western District of Texas:

In re: Hulu, LLC (Fed. Cir. No. 21-142): The panel (Taranto, Hughes, and Stoll, JJ.) granted Hulu’s petition, holding that Judge Albright clearly abused his discretion in evaluating Hulu’s transfer motion and denying transfer. In particular, the panel held that the district court at least erred in its analysis for each factor that it found weighed against transfer: (1) the availability of compulsory process to secure the attendance of witnesses; (2) the cost of attendance for willing witnesses; and (3) the administrative difficulties flowing from court congestion.

In re: Google LLC (Fed. Cir. No. 21-144): The panel (O’Malley, Reyna, and Chen, JJ.) denied Google’s petition because it did not “ma[k]e a clear and indisputable showing that transfer was required.” The district court had found that one or more Google employees in Austin, Texas were potential witnesses, and the panel was “not prepared on mandamus to disturb those factual findings.”

In re: Apple Inc. (Fed. Cir. No. 21-147): The panel (Reyna, Chen, and Stoll, JJ.) denied Apple’s petition because Apple did not show entitlement to the “extraordinary relief.” The panel did not, however, find that the district court’s analysis was free of error. For example, the panel explained, the district court “improperly diminished the importance of the convenience of witnesses merely because they were employees of the parties.”

In re: Dish Network L.L.C. (Fed. Cir. No. 21-148): The panel (O’Malley, Reyna, and Chen, JJ.) denied Dish’s petition but held that it “do[es] not view issuance of mandamus as needed here because” the panel was “confident the district court will reconsider its determination in light of the appropriate legal standard and precedent on its own.” The panel explained that, in light of In re Apple Inc., 979 F.3d 1332 (Fed. Cir. 2020), the district court erred in relying on Dish’s general presence in Western Texas without tying that presence to the events underlying the suit. The panel also explained that “[t]he need for reconsideration here” is additionally confirmed by In re Samsung Electronics Co., 2 F.4th 1371 (Fed. Cir. 2021), because the district court here improperly diminished the convenience of witnesses in the transferee venue because of their party status and by presuming they were unlikely to testify despite the lack of relevant witnesses in the transferor venue.

Gibson Dunn’s lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding developments at the Federal Circuit. Please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work or the authors of this alert:

Blaine H. Evanson – Orange County (+1 949-451-3805, bevanson@gibsondunn.com)

Jessica A. Hudak – Orange County (+1 949-451-3837, jhudak@gibsondunn.com)

Please also feel free to contact any of the following practice group co-chairs or any member of the firm’s Appellate and Constitutional Law or Intellectual Property practice groups:

Appellate and Constitutional Law Group:

Allyson N. Ho – Dallas (+1 214-698-3233, aho@gibsondunn.com)

Mark A. Perry – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3667, mperry@gibsondunn.com)

Intellectual Property Group:

Kate Dominguez – New York (+1 212-351-2338, kdominguez@gibsondunn.com)

Y. Ernest Hsin – San Francisco (+1 415-393-8224, ehsin@gibsondunn.com)

Josh Krevitt – New York (+1 212-351-4000, jkrevitt@gibsondunn.com)

Jane M. Love, Ph.D. – New York (+1 212-351-3922, jlove@gibsondunn.com)

© 2021 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP

Attorney Advertising: The enclosed materials have been prepared for general informational purposes only and are not intended as legal advice.

This week the UK Government published yet more updates on the application of the new National Security and Investment Act 2021 (NSI Act), which will come into effect on 4 January 2022.

Now seemed like a good time to take stock of all of the developments and guidance to date and to provide a helpful overview of the new regime, with all of the draft legislation and guidance in one place.

The big question is, what do companies need to take into account right now?

1. Background

In November last year, we reported on the UK Government’s announcement to overhaul the UK’s approach to foreign investment review and the introduction of its National Security and Investment Bill. The Bill received Royal Assent in April to become the NSI Act.

The NSI Act will introduce a new standalone hybrid regime of mandatory and voluntary notifications for certain acquisitions that could harm the UK’s national security. The regime also includes a Government power to call in any deal which raises a “national security risk”.

In late July 2021, the UK Government confirmed that the NSI Act will take effect from 4 January 2022 and also published four new pieces of guidance[1] as well as an updated draft of sector definitions for the mandatory notification regime under the NSI Act and a statement on how it proposes to exercise its new call-in powers.

This week the UK Government published a further updated draft of sector definitions for the mandatory notification regime and an explanatory note. Other than an amendment to state they will come into force on 4 January 2022, the draft definitions are in substantially the same form as the July draft. The Government also published draft regulations on monetary penalties under the NSI Act, together with an explanatory memorandum. These regulations are broadly in line with the rules for calculating penalties under the Enterprise Act 2002 (EA2002), but there are some differences.

2. Impact for companies

The introduction of the NSI Act forms part of a trend towards stricter control of foreign direct investment seen elsewhere in the world, including in the U.S. and in Europe. As far as foreign investment in the UK is concerned, the NSI Act will afford the UK Government one of the highest levels of scrutiny of any regime globally.

Although it is expected to be rare that a deal will be blocked (or require remedies) under the NSI Act, the impact for investors will be significant in terms of deal certainty and timeline.

The Government initially estimated that there will be 1,000–1,800 transactions notified each year, and 70 – 95 of those transactions are expected to be called in for a full national security assessment. This compares to a total of less than 25 transactions which have been reviewed by the Government since 2003 under the EA2002 public interest regime.[2] Since these estimates were made, the Government has increased the threshold for mandatory notification from the acquisition of 15% of shares or voting rights to 25%. Nonetheless, given the broad nature of the regime and the current uncertainty around its application, we would anticipate that a high number of notifications will be made, at least initially.

Faced with mandatory notification obligations in many cases, as well as severe criminal and civil consequences for non-compliance, companies must pay close attention to national security risks when investing in the UK.

3. What do companies need to consider right now?

Consider the existing public interest regime

Over the next four months, transactions which raise national security concerns are still subject to the existing public interest intervention regime under the EA2002 and, accordingly, parties should ensure their transaction documents adequately cater for both regimes. For example, in relation to conditions and the process and approach to preparing and securing relevant regulatory approvals.

The risk of intervention under the current regime is not theoretical. In the last few years, the numbers and the nature of intervention in UK transactions on public interest grounds has increased. In December 2019, the CMA issued a Public Interest Intervention Notice (PIIN) in relation to the proposed acquisition of Mettis Aerospace by Aerostar following which the parties decided not to proceed with the acquisition. In that same month the CMA issued a PIIN in relation to Gardener Aerospace’s proposed acquisition of Impcross Limited which was subsequently blocked.

More recently, in April of this year, Digital Secretary Oliver Dowden issued instructions in relation to the proposed acquisition of ARM Limited by NVIDIA Corporation. The Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) is reported as taking an active interest in Parker-Hannafin’s proposed acquisition of British defence technology firm, Meggitt. In August of this year, Director of National Security & International, Jacqui Ward, issued a PIIN in relation to Cobham’s proposed acquisition of the defence aerospace and security solutions provider, Ultra Electronics plc.

Once the NSI Act enters into force, the existing national security ground under the EA2002 will be repealed. However, the public health, media plurality and financial stability heads of intervention will remain in place and apply in parallel after commencement of the new NSI Act regime.

Make a jurisdictional assessment

Parties who are currently contemplating a deal that will complete after the commencement date (4 January 2022) need to assess whether their deal falls within the new mandatory notification regime. If so, the deal will need to be notified to the Investment Security Unit (ISU) of the Secretary of State for BEIS before closing.

An acquisition which is subject to the mandatory notification regime will be void if is completed without notifying and gaining approval from the Government. In such cases, parties need to ensure that their transaction documents contain appropriate conditions and that the long stop date is sufficient. Parties will need to take account of the time-frames that the ISU has to (i) determine whether to accept or reject a notification, (ii) assess whether they wish to issue a call-in notice and (iii) make its substantive assessment of the transaction, if it decides to call-in or screen the transaction.

Assess the risk of retrospective call-in for deals between 12 November 2020 and 4 January 2022

The NSI Act affords BEIS the power to retrospectively call-in deals and carry out a full national security assessment. These retroactive call-in powers apply to deals closed between 12 November 2020 and commencement of the NSI Act on 4 January 2022 (the interim period). They do not apply to deals closed before 12 November 2020.

This means that for deals contemplated now, even if they will close before 4 January 2022, parties have to carry out a risk assessment of the likelihood that BEIS will use its call-in powers post 4 January.

The call-in powers may be exercised where the Government reasonably suspects that a “trigger event” (see below) has occurred and that the trigger event has given rise or may give rise to a national security risk. If a transaction that closed in the interim period would have fallen within the mandatory regime had the NSI Act been in force at the time, it could be a prime candidate for call-in by BEIS once the NSI Act commences.[3]

For deals which closed in the interim period but would not have been caught by the mandatory regime, parties will still need to consider whether their deal may reasonably be considered to raise national security concerns within the meaning of the NSI Act. And, as such, whether the deal is a likely candidate for call-in by BEIS.

The period during which the Government can call-in a deal is five years from completion. This period is reduced to six months from the date at which the BEIS becomes aware of the transaction. For deals closing during the interim period, the call-in power will be available for a five year period from the date of closing, or six months from 4 January, if the parties informed BEIS of the transaction during the transitional period.

This is important because parties to a transaction which closes during the interim period and which could reasonably be considered to give rise to a national security, should consider whether to discuss the transaction informally with the ISU. Making BEIS aware through consultation with the ISU would have the effect of shortening the window for call-in to six months from commencement of the Act. It may also help parties decide whether a voluntary notification would be prudent once the Act commences. Such an approach may be advantageous from a deal certainty view point, in particular in terms of mitigating buy-side transactional risk.

4. A quick recap on the rules

4.1 What type of transactions does the NSI Act apply to?

The NSI Act applies to acquisitions of control over qualifying entities or assets – this is called a “trigger event” – where BEIS reasonably suspects that there is a risk to national security as a result of the acquisition.

The definition of control under the NSI Act is broad and applies to the acquisition of more than 25%, 50% and 75% of votes or shares in a qualifying entity (or the acquisition of voting rights that allow the acquirer to pass or block resolutions governing the affairs of the entity). In addition, outside of the mandatory regime, BEIS will also be able to call-in or accept voluntary notifications in relation to transactions falling below this 25% threshold where there is “material influence”. This can mean acquisitions of shareholdings as low as 10-5%.[4]

A qualifying entity must be a legal person, that is not an individual. It must have a tie to the UK, either because it is registered in the UK or because it carries on activities in the UK or supplies goods or services to persons in the UK.

Acquisitions of qualifying assets such as land and IP may be subject to call-in or the voluntary regime (but not the mandatory regime).[5]

4.2 Mandatory notifications

Notifications will be mandatory for acquisitions of control over a qualifying entity active in 17 defined sectors designated as particularly sensitive for national security. These are wide-ranging: from energy, defence and transport to AI, quantum technologies, and satellite and space technologies.[6] In these sectors, such transactions must receive Government approval before completion and so the NSI Act has a suspensory effect.

Failure to notify under the mandatory regime will render completion of the acquisition void. There are also civil and criminal penalties for completing a notifiable acquisition without approval. Civil penalties can be up to 5% of the organization’s global turnover or £10 million (whichever is greater).[7]

The Government has engaged extensively with stakeholders on the mandatory sector definitions, since the publication of the first draft in November 2020. Throughout this process, the Government has refined and developed the proposed definitions. The latest set of definitions were published on 6 September and are set out in the draft notifiable acquisition regulation. These are broadly in line with what the Government has published previously. The Government has indicated that it will continue to refine its definitions, even after commencement of the NSI Act in January.

One important point in the guidance issued in July[8] is that a qualifying entity falls within a description of the 17 mandatory sectors only if it carries on the activity specified in the UK or supplies relevant goods or services in the UK.[9]

4.3 Call-in and voluntary notifications

Acquisitions of control over qualifying entities outside of the 17 mandatory regime sectors do not need to be notified. But, if the Government reasonably suspects that an acquisition has given rise to, or may give rise to, a risk to national security, it can be scrutinized by the Government using its call-in powers.

Given these expansive call-in powers, parties may decide to voluntarily notify their transactions where there is a perceived risk of call-in and a desire for deal certainty. A voluntary notification forces BEIS to decide within 30 business days whether to proceed with a review.

As noted above, the voluntary regime may also apply to asset acquisitions and to transactions falling below this 25% threshold where there is “material influence”.[10]

5. How to assess the call-in risk

The Government published a new draft statement in July, setting out how it expects to exercise the power to give a call-in notice. This is referred to as the draft statement for the purposes of section 3. The Government again consulted on this statement, with the consultation closing on 30 August.

Whilst qualifying acquisitions across the whole economy are technically in scope, the call-in power will be focussed on acquisitions in the 17 areas of the economy subject to mandatory notification and areas of the economy which are closely linked to these 17 areas. Acquisitions which occur outside of these areas are unlikely to be called in because national security risks are expected to occur less frequently in those areas. This is new compared to the previous statement of intent of policy, which split areas of the economy into three risk levels (core areas, core activities and the wider economy), and is a welcome clarification.

The risk factors have stayed largely the same as in previous iterations, with some tweaks. Essentially, to assess the likelihood of a risk to national security, the Secretary of State will consider three risk factors:

- Target risk: whether the target is being used, or could be used, in a way that poses a risk to national security. BEIS will consider what the target does, is used for, or could be used for, and whether that could give rise to a risk to national security. BEIS will also consider any national security risks arising from the target’s proximity to sensitive sites.

- Acquirer risk: whether the acquirer has characteristics that suggest there is, or may be, a risk to national security from the acquirer having control of the target. Characteristics include sector(s) of activity, technological capabilities and links to entities which may seek to undermine or threaten the interests of the UK. Threats to the interests of the UK include the integrity of democracy, public safety, military advantage and reputation or economic prosperity. Some characteristics, such as a history of passive or longer-term investments, may indicate low or no acquirer risk.

- Control risk: whether the amount of control that has been, or will be, acquired poses a risk to national security. A higher level of control may increase the level of national security risk.

The risk factors will be considered together, but an acquisition may be called in if any one risk factor raises the possibility of a risk to national security.

The same risk factors will be applied to qualifying acquisitions of assets as to qualifying acquisitions of entities.

At present there are no turnover or market share safe-harbours for investors (below which transactions would fall outside the scope of the NSI Act). The Government has, to date, firmly rejected calls from industry professionals and practitioners to introduce such a safe-harbour or exemption.

6. What’s next?

We expect the Government to publish final regulations and guidance as the year draws to an end. We do not expect the scope of the 17 sensitive sectors to change now, before the NSI Act comes into effect.

In the meantime, parties should consider the possible impact of the new regime on any proposed divestments or acquisitions which are in the mandatory sectors or which are not in one of these designated sectors but which may nonetheless give rise to national security concerns. The ISU has encouraged parties to contact them to discuss possible acquisitions and how the NSI Act may impact their transaction or their responsibilities.

More generally, the Government has emphasised that the UK remains open for investment and that the new regime aims to proportionately mitigate national security risks. It is keen to stress its ambition that the new regime will enable the fastest, most proportionate foreign investment screening in the world, while not undermining predictability and certainty.

_______________________

[1] (i) How to Prepare for the New NSIA Rules on Acquisitions; (ii) Application of the NSIA to People or Acquisitions Outside the UK; (iii) Guidance for the Higher Education & Research Intensive Sectors; and (iv) NSIA and Interaction with Other UK Regulatory Regimes.

[2] The Government’s powers to review transactions on public interest grounds are currently set out in the Enterprise Act 2002. The Government can issue a Public Interest Intervention Notice (PIIN) on certain strictly defined public interest considerations. It can only do so where a transaction meets the jurisdictional thresholds under the UK merger control rules (with limited exceptions).

[3] For such transactions, which were legitimately closed before commencement, the suspension obligation does not apply and there can be no fines for failing to notify.

[4] The Government has stated that any assessment of an acquisition of material influence under the NSI Act will follow the CMA’s guidance on material influence in a merger control context.

[5] The Government has indicated that investigations of asset acquisitions that are not linked to the 17 mandatory sectors are expected to be rare and, generally, the Secretary of State expects to call-in acquisitions of assets rarely and significantly less frequently than acquisitions of entities.

[6] The full list is: Advanced Materials, Advanced Robotics, Artificial Intelligence, Civil nuclear, Communications, Computing hardware, Critical suppliers to Government, Critical suppliers to the emergency services, Cryptographic Authentication, Data Infrastructure, Defence, Energy, Military and Dual-use, Quantum technologies, Satellite and space technologies, Synthetic biology, Transport.

[7] See draft regulations on monetary penalties and the accompanying explanatory memorandum published on 6 September 2021.

[8] See guidance referred to in item (i) in footnote 1.

[9] The guidance also the proposed Section 3 statement (see section 4 of this alert below) provides helpful examples and case studies of the types of entities and assets both in and outside of the UK which may fall within scope of the new regime.

Gibson Dunn’s lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions that you may have regarding the issues discussed in this update. For further information, please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, any member of the firm’s Antitrust and Competition, Mergers and Acquisitions, or International Trade practice groups, or the authors:

Ali Nikpay – Antitrust and Competition (+44 (0) 20 7071 4273, anikpay@gibsondunn.com)

Deirdre Taylor – Antitrust and Competition (+44 (0) 20 7071 4274, dtaylor2@gibsondunn.com)

Selina S. Sagayam – International Corporate (+44 (0) 20 7071 4263, ssagayam@gibsondunn.com)

Attila Borsos – Competition and Trade (+32 2 554 72 11, aborsos@gibsondunn.com)

Mairi McMartin – Antitrust and Competition (+32 2 554 72 29, mmcMartin@gibsondunn.com)

© 2021 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP

Attorney Advertising: The enclosed materials have been prepared for general informational purposes only and are not intended as legal advice.

On 2 September 2021, the Court of Justice of the European Union (the “CJEU”) issued its ruling in Republic of Moldova v Komstroy[1] (the “Decision” or “Komstroy”) concluding that, as a matter of EU law, Article 26 of the Energy Charter Treaty (the “ECT”) is not applicable to “intra-EU” disputes (that is, disputes between an investor of an EU Member State on the one hand, and an EU Member State on the other).

The CJEU’s Decision largely follows the CJEU’s controversial reasoning in Achmea BV v Slovak Republic[2] (“Achmea”) (2018), which concerned a bilateral investment treaty (“BIT”) between two EU Member States (as opposed to a multilateral treaty such as the ECT). Achmea was addressed in a previous client alert here.[3]

Background

In October 2019, the Paris Court of Appeal (cour d’appel de Paris) made a request to the CJEU for a preliminary ruling addressing three questions.[4] These pertained to set-aside proceedings brought by Moldova in respect of an UNCITRAL arbitral award rendered against it for certain breaches of obligations under the ECT. Paris was the seat of the underlying arbitration.

The CJEU’s Decision

Only one of the three questions referred by the Paris Court of Appeal ultimately was addressed by the CJEU. That question asked the CJEU to determine whether the definition of “investment” in Article 1(6) of the ECT requires any economic contribution on the part of the investor in the host State. The Decision found, in essence, that an economic contribution was required in its view.

The CJEU also set out its views on whether Article 26 of the ECT is compatible with EU law insofar as it provides for arbitration between EU based investors and EU Member States.[5] This question was not referred by the Paris Court of Appeal, nor was it directly relevant to the questions before the CJEU (which concerned investments in a non-EU Member State (Moldova)). This separate question had been raised by the European Commission, together with certain EU Member States,[6] acting as interveners in the CJEU proceedings. The Decision indicates that intra-EU arbitration under the ECT is incompatible with EU law. The CJEU’s reasoning is summarised below.

First, following its reasoning in Achmea, the CJEU explained that in order to preserve the autonomy of EU law, as well as its effectiveness, national courts of EU Member States may make a preliminary reference to the CJEU pursuant to Article 267 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (the “TFEU”). This referral procedure was described as the “keystone” of the EU judicial system with the “objective of securing the uniform interpretation of EU law, thereby ensuring its consistency, its full effect and its autonomy”.[7]

Second, the CJEU reasoned that because the EU is a Contracting Party to the ECT, the ECT itself is a so-called “act of EU law”.[8] Having reached this conclusion, the CJEU then determined that because the ECT is an “act of EU law”, an ECT tribunal would necessarily be required to interpret, and even apply, EU law when deciding a dispute under Article 26.[9] This reasoning appears to be directly at odds with the CJEU’s Opinion 1/17, in which it accepted that CETA tribunals[10]– though standing outside the judicial system of the EU – could nonetheless interpret and apply the CETA itself without running afoul of EU law.[11] The Decision does not explain how CETA, to which the EU is also a party and must likewise be considered an “act of the EU” by the CJEU, can be compatible with EU law, but the ECT cannot. Likewise, the CJEU did not explain how its finding that the ECT is an “act of EU law” would not apply equally in the extra-EU context (i.e., where a dispute involves an EU Member State and an investor from a third State), leaving these questions unanswered.

Third, having found that an ECT tribunal would need to apply EU law on the basis that the ECT is an “act of EU law”, the CJEU then ascertained whether an ECT tribunal is situated within the judicial system of the EU such that a preliminary reference could be made to the CJEU to ensure the effectiveness of EU law.[12] In the CJEU’s view – in “precisely the same way” as in Achmea – ECT tribunals are outside the EU legal system, thus preventing effective control over EU law.[13] The CJEU found that the judicial review that arises in the context of EU-seated investor-state arbitration is limited since the referring court can only perform a review insofar as its domestic law permits.[14] In other words, according to the CJEU, the full effectiveness of EU law cannot be guaranteed.

Finally, given that commercial arbitration tribunals routinely interpret and apply EU law outside of the EU legal system (which could mean that any arbitration would be incompatible with EU law), the Decision attempts to distinguish investor-state arbitration from commercial arbitration. The distinction, according to the CJEU, is that commercial arbitration is different because it “originate[s] in the freely expressed wishes of the parties concerned”, whereas investor-state arbitration apparently is not based on the parties’ “freely expressed wishes”.[15] Unfortunately, however, the CJEU did not elaborate on its conclusion in this regard. That conclusion appears to be inconsistent with well-established principles of public international law, which confirm that States can (and must) enter into treaties such as the ECT of their own free will.

In light of the foregoing, the CJEU concluded that Article 26 of the ECT is incompatible with EU law insofar as it provides for arbitration between EU investors and EU Member States.[16]

Implications of the CJEU’s Decision

The ECT remains in force between all Contracting Parties, which includes all EU Member States, as well as the EU. Indeed, a modification of the ECT to remove its application as between EU Member States would require the participation not just of the EU and its Member States, but of all 53 Contracting Parties to the ECT. The CJEU’s Decision does not (and cannot) modify the express terms of the ECT itself.

To date, all ECT tribunals that have considered jurisdictional objections based on the intra-EU nature of the dispute have rejected the suggestion that the ECT does not apply on an intra-EU basis. That is unlikely to change in light of the Decision. Indeed, the CJEU did not offer any analysis under the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (the “VCLT”), which governs the interpretation of the ECT. Nor did the CJEU address the substantial body of case law under the ECT on the interpretation of Article 26 of the ECT, all of which reaches the opposite conclusion to the CJEU. Those cases set forth what is now a well-established principle that EU law is not relevant to the question of jurisdiction under the ECT. Thus, the Decision (which is limited to an analysis under EU law) should have no bearing on an ECT tribunal’s jurisdiction.

Another implication of the Decision is that EU-based investors considering energy investments in EU Member States may now view these investments as more risky. First, the applicability of Article 26 to intra-EU disputes was not a question that was before the CJEU and it had no impact on the Komstroy case, which (paradoxically) did not involve an intra-EU dispute. The Decision provides scant and inconsistent reasoning and may therefore be considered to be based on political considerations rather than a sound and reasoned interpretation of the law. The Decision thus has the potential to undermine investor confidence in the EU judicial system and the rule of law within the EU.

Second, the CJEU’s Decision may create uncertainty regarding the extent of investor protection within the EU for energy investments as EU Member States may believe that they can (or must) disapply the ECT to investors from other EU Member States. This, of course, would make investments by EU investors into EU Member States both less attractive and more expensive (as it will drive up risk premiums). The CJEU’s decision may, therefore, undermine investor confidence at a time when the EU is seeking substantial private investment in its energy sector as part of its efforts to de-carbonise. In other words, the Decision ultimately could be an “own goal” for the EU and its Member States.

____________________________

[1] Judgment of the Court (Grand Chamber), Case C‑741/19, Republic of Moldova v Komstroy, a company the successor in law to the company Energoalians, ECLI:EU:C:2021:655, 2 September 2021 (the “Decision”), available here.

[2] Judgment of the Court (Grand Chamber), Case C‑284/16, Slowakische Republik (Slovak Republic) v Achmea BV, ECLI:EU:C:2018:158, 6 March 2018, available here.

[3] In short, in Achmea, the CJEU determined that arbitration provisions such as the one found in the intra-EU BIT at issue in that case (which, in contrast to the ECT, explicitly required a tribunal to consider EU law) are not compatible with EU law.

[4] Request for a preliminary ruling from the Cour d’appel de Paris, Case C-741/19, Republic of Moldova v Komstroy, a company the successor in law to the company Energoalians, 8 October 2019, available here.

[6] France, Germany, Spain, Italy, The Netherlands and Poland.

[10] I.e., tribunals established to hear disputes arising under the under the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (“CETA”).

[11] Opinion 1/17 of the Full Court (CETA), ECLI:EU:C:2019:341, 20 April 2019, ¶¶ 116-118, available here.

[12] See Article 267 TFEU (the preliminary reference procedure).

The following Gibson Dunn lawyers assisted in the preparation of this client update: Jeff Sullivan QC, Ceyda Knoebel, Stephanie Collins and Theo Tyrrell.

Gibson Dunn’s lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding these issues. Please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, any member of the firm’s International Arbitration, Judgment and Arbitral Award Enforcement or Transnational Litigation practice groups, or any of the following in London:

Cyrus Benson (+44 (0) 20 7071 4239, CBenson@gibsondunn.com)

Penny Madden QC (+44 (0) 20 7071 4226, PMadden@gibsondunn.com)

Jeff Sullivan QC (+44 (0) 20 7071 4231, Jeffrey.Sullivan@gibsondunn.com)

Ceyda Knoebel (+44 (0) 20 7071 4243, CKnoebel@gibsondunn.com)

Stephanie Collins (+44 (0) 20 7071 4216, SCollins@gibsondunn.com)

Theo Tyrrell (+44 (0) 20 7071 4016, TTyrrell@gibsondunn.com)

© 2021 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP

Attorney Advertising: The enclosed materials have been prepared for general informational purposes only and are not intended as legal advice.

|

1. |

INTRODUCTION |

|

1.1 |

Singapore has become an increasingly popular destination for trust listings in the recent years. Real estate investment trusts (“REITs”), business trusts (“BTs”) and stapled trusts are some of the more popular vehicles that property players opt for to tap capital on Singapore Exchange Securities Trading Limited (the “SGX-ST”). |

|

1.2 |

This primer provides an overview of the structure of such vehicles, the main regulations regulating them, the process to getting listed on the SGX-ST as well as the various ways of acquiring control of these vehicles post-listing. This primer also explores the lessons to be learnt from the controversy surrounding Eagle Hospitality Trust (“EHT”) and the failed merger between ESR REIT and Sabana REIT. |

|

2. |

STRUCTURE |

|

2.1 |

REIT |

|

2.1.1 |

A REIT may generally be described as a trust that invests primarily in real estate and real estate-related assets with the view to generating income for its unitholders. | |||||||||

|

2.1.2 |

It is constituted pursuant to a trust deed entered into between the REIT manager and the REIT trustee. | |||||||||

|

2.1.3 |

The REIT manager manages the assets of the REIT while the REIT trustee holds the assets on behalf of the unitholders and generally helps to safeguard the interests of the unitholders. | |||||||||

|

2.1.4 |

REITs are popular with investors as the income from the assets (after deducting trust expenses) is distributed to the unitholders at regular intervals. A REIT which distributes at least 90% of its taxable income to its unitholders in the same year in which the income is derived can enjoy tax transparency treatment under the Income Tax Act, Chapter 134 of Singapore. It is also not uncommon for REITs to pledge to distribute the entire of its annual distributable income in the initial period post-listing. | |||||||||

|

2.1.5 |

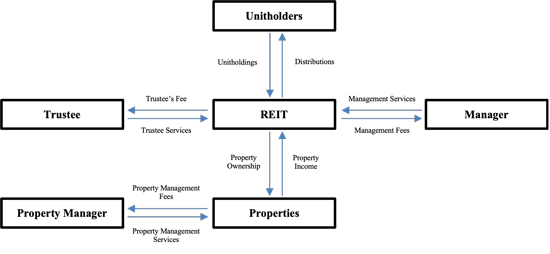

The typical roles in a REIT structure are as follows: | |||||||||

|

| |

|

Typical REIT Structure |

|

2.1.6 |

SGX-ST-listed REITs typically adopt an external management model where the REIT manager is owned by the sponsor of the REIT. This is in contrast to an internal management model (adopted by a majority of REITs in the United States of America) where the REIT manager is instead owned by the REIT itself. Proponents of an internal management model in Singapore argue that an internal management model avoids conflicts of interest and lowers the fees payable to the REIT manager (which ultimately translates to better returns for unitholders). The success of the Hong Kong-listed internally managed Link REIT, Asia’s largest REIT in terms of market capitalization, may bear testament to this. However, whether an internal management model takes off in Singapore remains to be seen. Singapore investors could well prefer sponsor participation due to the various advantages that a sponsor can bring, such as marketability, expertise, support and pipeline of assets. |

|

2.2 |

BT |

|

2.2.1 |

A BT is a trust that can generally engage in any type of business activity, including the management of real estate assets or the management or operation of a business. | |||||||

|

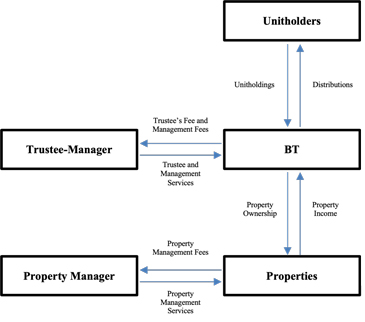

2.2.2 |

It is constituted pursuant to a trust deed entered into by the trustee-manager, a single entity that has the dual responsibility of safeguarding the interests of the unitholders of the BT and managing the business conducted by the BT. | |||||||

|

2.2.3 |

BTs, unlike companies, can make distributions out of operating cash flows (instead of profits). They suit businesses which involve high initial capital expenditures with stable operating cash flows, such as real estate assets. | |||||||

|

2.2.4 |

Compared to REITs, BTs are also more lightly regulated and may therefore be preferred for their flexibility. Property BTs often also pledge to provide REIT-like distributions to the unitholders. | |||||||

|

2.2.5 |

The typical roles in a BT structure are as follows: | |||||||

|

| |

|

Typical Property BT Structure |

|

2.3 |

Stapled Trust |

|

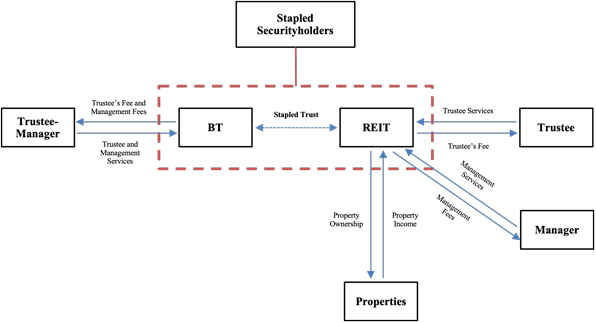

2.3.1 |

A stapled trust on the SGX-ST typically comprises a REIT and a BT. Pursuant to a stapling deed, units of the REIT and units of the BT are stapled together and cannot be traded separately. The REIT and the BT would continue to exist as separate structures, but the stapled securities would trade as one counter and share the same investor base. | |

|

2.3.2 |

A stapled trust structure may be preferred when an issuer wishes to bundle two distinct (but related) businesses into a single tradeable counter. Such stapled trust structure is commonly adopted for hospitality assets which provide both a passive (through the receipt of rental income from the lease of such assets) and an active (through the management and operation of such assets) income stream. | |

|

2.3.3 |

In such cases, the REIT will be constituted to hold the income-producing real estate assets and the BT will be constituted to either (a) be the master lessee of the real estate assets who will manage and operate these assets or (b) remain dormant and only step in as a “master lessee of last resort” to manage and operate these assets when there are no other suitable master lessees to be found. The presence of a BT also offers flexibility for the stapled trust to undertake certain hospitality and hospitality-related development projects, acquisitions and investments which may not be suitable for the REIT. | |

|

2.3.4 |

Investors who value the business and income diversification may therefore find such a model attractive. | |

|

2.3.5 |

The typical roles in a REIT and a BT have been discussed above. |

| |

|

Typical Stapled Trust Structure |

|

3. |

REGULATIONS | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

3.1 |

REIT | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

3.2 |

BT | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

3.3 |

Stapled Trust | ||||

|

|

4. |

LISTING | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

4.1 |

Due Diligence | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

4.2 |

Listing Process | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

4.3 |

Prospectus | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

4.4 |

Continuing Listing Obligations | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Post-listing, REITs, BTs and stapled trusts are subject to continuing listing obligations under the Listing Manual, such as the requirement to announce specific and material information, requirements relating to secondary offerings, interested person transactions and significant transactions, as well as requirements relating to circulars and annual reports. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

4.5 |

Case Study of EHT | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

5. |

Acquiring Control of a REIT, BT or Stapled Trust | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

5.1 |

An acquisition of all the units of a REIT or BT or all the stapled securities of a stapled trust listed on the SGX-ST (“Target Entity”) may be effected in various ways, such as a take-over offer, a trust scheme of arrangement (“Trust Scheme”) and a reverse take-over (“RTO”). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

5.2 |

Any merger or acquisition involving a Target Entity would be subject to the Listing Manual, the CIS Code (in the case of a REIT) and the Singapore Code on Take-overs and Mergers (the “Take-over Code”). The Take-over Code is enforced by the Securities Industries Council (the “SIC”), which is part of the MAS. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

5.3 |

Take-over Offer | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

5.4 |

Trust Scheme | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

5.5 |

RTO | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

5.6 |

Which method to adopt? | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Gibson Dunn’s lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding these issues. Please feel free to contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, or the authors of this primer in the firm’s Singapore office:

Robson Lee (+65.6507.3684, RLee@gibsondunn.com)

Kai Wen Chua (+65.6507.3658, KChua@gibsondunn.com)

Zan Wong (+65.6507.3657, ZWong@gibsondunn.com)

© 2021 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP

Attorney Advertising: The enclosed materials have been prepared for general informational purposes only and are not intended as legal advice.

The UK’s Competition Appeal Tribunal (the CAT) has certified the first application for a collective proceedings order (CPO) on an opt-out basis in Walter Hugh Merricks CBE v Mastercard Incorporated & Ors.

In the UK, a CPO is pre-requisite for opt-out collective actions seeking damages for breaches of competition law. Opt-out means that an action can be pursued on behalf of a class of unnamed claimants who are deemed included in the action unless they have specifically opted out. Opt-out ‘US style’ class actions have the potential to be far more complex, expensive and burdensome than traditional named party litigation.

Opt-out class actions were introduced for the first time in the UK in 2015 (see our previous alert here). Almost six years on, last week’s judgment by the CAT is therefore an important procedural step towards the first opt-out class action damages award in the UK.

As had been expected, following the Supreme Court’s judgment in December 2020 (see our previous alert here) Mastercard did not resist certification outright. As a result, the CAT’s most recent judgment provides little further clarity on how the test set out in the Supreme Court’s judgment will be applied to future applications for a CPO. However, the CAT’s recent judgment did address certain interesting questions concerning suitability to act as a class representative, whether deceased persons could be included in the proposed class and the suitability of claims for compound interest. These are discussed in more detail below.

Background