Palo Alto partner Mark Lyon is the author of “Gearing up for the EU’s next regulatory push: AI,” [PDF] published in the Daily Journal on October 11, 2019.

Los Angeles partner Michael Dore is the author of “Overt Activities: The Ethical Implications of Government Contacts with Represented Parties,” [PDF] published in the Los Angeles Lawyer in October 2019.

The California Consumer Privacy Act of 2018 becomes effective in 77 days (January 1, 2020), and offers California residents several new privacy rights through obligations placed on covered businesses. For a more in-depth look at the CCPA, see our previous client alerts summarizing the statute (here), amendments from October 2018 (here), additional proposed amendments (here), and the Attorney General’s regulations posted last week (here).

Over the last several months, and prior to the release of the regulations, the California legislature worked on several additional amendments to the law that at long last have been signed by Governor Gavin Newsom—less than three months before CCPA takes effect. Like the regulations, these amendments respond to concerns raised after the passage of the CCPA. The signed amendments do not critically change the original core requirements of the CCPA, but may offer some clarification and even reprieve in certain areas for many of our clients.[1]

Finalized Amendments

Partial and Temporary Employment-Related Exemptions – AB 25

AB 25 provides a one-year exception for employers who feared that the consumer protection law inadvertently crept into covering employment-related information. The bill clarifies that the CCPA generally will not apply to personal information that is collected about job applicants, employees, contractors, and other employment-related roles. The bill also creates exemptions for employee emergency contact information and personal information necessary to administer benefits. Importantly, the bill does not relieve employers of the “private civil action provision [for data breaches] and the obligation to inform the [employee] as to the categories of personal information to be collected.”[2] And these exemptions only extend to “personal information [that] is collected and used by the business solely within the context of the natural person’s role or former role . . .”, which may create uncertainty for areas of potential business and personal overlap. The bill also only provides temporary relief for employers in that these exceptions become inoperative on January 1, 2021, absent further legislative action in the coming year.[3]

Redefinition of Personal and Publicly Available Information – AB 874

This bill clarifies the terms “publicly available” and “personal information.” Most significantly, the bill removes the requirement that publicly available information must be compatible with the purpose for which the data is maintained and made available in order to be exempt. Information lawfully made available in federal, state or local government records therefore will be considered “publicly available” and excluded from the definition of personal information, regardless of the purpose for which they are used; this may be a significant relief for companies using publicly available government-collected data, at least with respect to compliance relating to those categories of information. That said, the definition of “publicly available” remains narrow, and “personal information” covered by CCPA would still include non-governmental information posted publicly by the consumer.

This amendment also clarifies the definition of “personal information” by adding the term “reasonably”—again—to read as “information that identifies, relates to, describes, is reasonably capable of being associated with, or could reasonably be linked, directly or indirectly, with a particular consumer or household.” Under the CCPA, “personal information” is a key term for information that would be protected and subject to various requirements. The bill would also exclude deidentified or aggregated consumer information from the “personal information” definition (a similar clarification for deidentified information is also provided by AB 1355).

Business-to-Business Exceptions and Various Technical Amendments – AB 1355

AB 1355 creates a one-year exception for personal information collected in the course of certain business-to-business interactions, and makes various minor technical amendments. During the last several weeks of the legislative session, legislators added an exception for business-to-business transactions when considering “personal information . . . where the consumer is . . . acting as an employee, owner, director, officer, or contractor of a company . . . and whose communications or transaction with the business occur solely within the context of the business conducting due diligence regarding, or providing or receiving a product or service to or from such company. . . .” This exception would not apply to other circumstances (e.g., when the consumer’s information is additionally used for other purposes), the consumer’s right to “opt-out” of selling, the right to non-discrimination, or the data breach private right of action. And like AB 25, this is only a temporary reprieve. The exemption is only valid until January 1, 2021. Nonetheless, for the first year of CCPA, this amendment provides clarity for businesses who mostly function in a business-to-business capacity, and may collect personal information from business agents in that course.

This bill also makes a number of more minor clarifications, cross-reference corrections and conforming changes to the act. Among the notable changes, this bill, like AB 874, clarifies that deidentified or aggregated consumer information is excluded from the definition of personal information and also clarifies the CCPA’s non-discrimination exception. Under the original Act, businesses could exercise certain discrimination if the differential treatment is reasonably related to value provided to the consumer by the consumer’s data. The bill modifies this exception for differential treatment related to value provided to the business by the consumer’s data.

Data Broker Registration – AB 1202

AB 1202 amends the CCPA to require that “data brokers” register with the California General’s Office on an annual basis. The bill broadly defines “data broker” as any “business that knowingly collects and sells to third parties the personal information of a consumer with whom the business does not have a direct relationship.” According to the bill’s text, direct relationships may be created in a “variety of ways such as by visiting a business’ premises or internet website, or by affirmatively and intentionally interacting with a business’ online advertisements . . . .”[4]; however, many businesses that collect information from sources other than the consumer, and then use that information downstream for a business purpose (including “selling”), may be implicated.[5] Data brokers who fail to comply with the law are subject to injunctions, civil penalties, fees, and costs for actions brought by the Attorney General. Civil penalties include fines of $100 for each day the data broker failed to register.

Contact Information for Consumer Requests – AB 1564

Under the original act, businesses were required to have a toll-free phone number to facilitate consumer requests. This bill creates an exception for a business that operates exclusively online and has a direct relationship with a consumer data subject. These online businesses are required to make an email address available for requests (and based on the recently proposed regulations, also a web form), but are not required to add a toll-free phone number. Nonetheless, the Act and regulations still require two modes of contact.

Vehicle Information – AB 1146

This amendment creates sectoral exceptions for the auto industry. Under the CCPA, consumers have an opt-out right to ask businesses not to sell information to third parties and have the right to ask business to delete certain consumer information. This bill allows businesses to exclude vehicle information from the opt-out and deletion provisions for the “purpose of effectuating or in anticipation of effectuating a vehicle repair covered by a vehicle warranty or a recall . . . .”

Other Amendments that May Affect CCPA

The California legislature also has passed laws that can shape the CCPA, without being amendments to the law itself. Businesses should consider how these laws may expand liability under the CCPA for their companies.

Data Breach Amendments – AB 1130

On October 11, Governor Newsom signed a bill that would expand the definition of “personal information” in the state’s data breach notification law by including “specified unique biometric data and tax identification numbers, passport numbers, military identification numbers, and unique identification numbers issued on a government document in addition to those for driver’s licenses and California identification cards . . . .” While this law does not modify the CCPA directly, the amendment’s expansion of personal information broadens the list of personal information subject to the data breach private right of action in CCPA, as the private right of action’s definition of “personal information” depends on the definition in the data breach statute.

Police Body Cameras – AB 1215

On October 9, Governor Newsom signed a bill that will ban law enforcement use of facial recognition technology on body-worn cameras for three years. While this also does not modify any substantive provisions of the CCPA, the new law further regulates the collection of personal information, sounds in California’s concern for overly broad collection of information, and may influence modifications to the CCPA regarding facial recognition (such as AB 1281, which would require businesses to give conspicuous notices where facial recognition technology is employed). Law enforcement entities must cease this application of the technology by January 1, 2020.

* * *

The foregoing amendments present several clarifications to businesses working to comply with CCPA, and under certain instances institute additional burden. We continue to monitor developments regarding the CCPA, including the recently released regulations from the Office of the Attorney General, and are available to discuss these issues as applied to your particular business.

________________________

[1] Also notable is a significant bill that did not pass this legislative session—SB 561—which would have greatly expanded potential liability for businesses by creating a private right of action for any CCPA violation. As a result, the only private right of action under the CCPA remains actions for certain data breaches. However, businesses should continue to monitor SB 561 (and any others like it) in the next legislative session (one may recall that the CCPA itself was retrieved from the inactive file).

[2] Legislative Counsel’s Digest, A.B. 25 (CA 2019)

[3] Legislative action specific to employment-related data may well be expected, as the Senate amended the bill to exempt this information for only a year, as a compromise (whereas there was no limitation in the original bill), on the premise that there would be consideration of how to address employment-related information in particular during the next legislative session. During the public comment period a number of speakers addressed the concern for the CCPA becoming an employment law—attenuated from its original intent to protect consumers.

[4] The requirement will yield to certain federal laws; businesses covered by the federal Fair Credit Reporting act, Insurance Information and Privacy Protection Act and Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act are exempted from the data broker registration requirement.

[5] California’s bill fits into a national tableau of increasing data broker regulation. Last summer, Vermont passed H. 764, which required data brokers to register with the state government and produce certain reports about their data collection. Like California, Vermont cast a wide net for covered entities through a capacious definition: “‘Data broker’ means a business, or unit or units of a business, separately or together, that knowingly collects and sells or licenses to third parties the brokered personal information of a consumer with whom the business does not have a direct relationship.” 9 V.S.A. § 2430(4)(A).

The following Gibson Dunn lawyers assisted in the preparation of this client update: Alex Southwell, Mark Lyon, Cassandra Gaedt-Sheckter, Arjun Rangarajan and Tony Bedel.

Gibson Dunn’s lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding these developments. Please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, or any member of the firm’s California Consumer Privacy Act Task Force or its Privacy, Cybersecurity and Consumer Protection practice group:

California Consumer Privacy Act Task Force:

Ryan T. Bergsieker – Denver (+1 303-298-5774, [email protected])

Cassandra L. Gaedt-Sheckter – Palo Alto (+1 650-849-5203, [email protected])

Joshua A. Jessen – Orange County/Palo Alto (+1 949-451-4114/+1 650-849-5375, [email protected])

H. Mark Lyon – Palo Alto (+1 650-849-5307, [email protected])

Arjun Rangarajan – Palo Alto (+1 650-849-5398, [email protected])

Alexander H. Southwell – New York (+1 212-351-3981, [email protected])

Deborah L. Stein (+1 213-229-7164, [email protected])

Eric D. Vandevelde – Los Angeles (+1 213-229-7186, [email protected])

Benjamin B. Wagner – Palo Alto (+1 650-849-5395, [email protected])

Please also feel free to contact any member of the Privacy, Cybersecurity and Consumer Protection practice group:

United States

Alexander H. Southwell – Co-Chair, PCCP Practice, New York (+1 212-351-3981, [email protected])

M. Sean Royall – Dallas (+1 214-698-3256, [email protected])

Debra Wong Yang – Los Angeles (+1 213-229-7472, [email protected])

Olivia Adendorff – Dallas (+1 214-698-3159, [email protected])

Matthew Benjamin – New York (+1 212-351-4079, [email protected])

Ryan T. Bergsieker – Denver (+1 303-298-5774, [email protected])

Richard H. Cunningham – Denver (+1 303-298-5752, [email protected])

Howard S. Hogan – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3640, [email protected])

Joshua A. Jessen – Orange County/Palo Alto (+1 949-451-4114/+1 650-849-5375, [email protected])

Kristin A. Linsley – San Francisco (+1 415-393-8395, [email protected])

H. Mark Lyon – Palo Alto (+1 650-849-5307, [email protected])

Karl G. Nelson – Dallas (+1 214-698-3203, [email protected])

Deborah L. Stein (+1 213-229-7164, [email protected])

Eric D. Vandevelde – Los Angeles (+1 213-229-7186, [email protected])

Benjamin B. Wagner – Palo Alto (+1 650-849-5395, [email protected])

Michael Li-Ming Wong – San Francisco/Palo Alto (+1 415-393-8333/+1 650-849-5393, [email protected])

Europe

Ahmed Baladi – Co-Chair, PCCP Practice, Paris (+33 (0)1 56 43 13 00, [email protected])

James A. Cox – London (+44 (0)20 7071 4250, [email protected])

Patrick Doris – London (+44 (0)20 7071 4276, [email protected])

Bernard Grinspan – Paris (+33 (0)1 56 43 13 00, [email protected])

Penny Madden – London (+44 (0)20 7071 4226, [email protected])

Michael Walther – Munich (+49 89 189 33-180, [email protected])

Kai Gesing – Munich (+49 89 189 33-180, [email protected])

Sarah Wazen – London (+44 (0)20 7071 4203, [email protected])

Vera Lukic – Paris (+33 (0)1 56 43 13 00, [email protected])

Alejandro Guerrero – Brussels (+32 2 554 7218, [email protected])

Asia

Kelly Austin – Hong Kong (+852 2214 3788, [email protected])

Jai S. Pathak – Singapore (+65 6507 3683, [email protected])

© 2019 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP

Attorney Advertising: The enclosed materials have been prepared for general informational purposes only and are not intended as legal advice.

The False Claims Act (FCA) is well-known as one of the most powerful tools in the government’s arsenal to combat fraud, waste and abuse anywhere government funds are implicated. The U.S. Department of Justice has recently issued statements and guidance indicating some new thinking about its approach to FCA cases that may signal a meaningful shift in its enforcement efforts. But at the same time, newly filed FCA cases remain at historical peak levels and the DOJ has enjoyed eight straight years of nearly $3 billion or more in annual FCA recoveries. As much as ever, any company that deals in government funds—especially in the health care and life sciences sector—needs to stay abreast of how the government and private whistleblowers alike are wielding this tool, and how they can prepare and defend themselves.

Please join us to discuss developments in the FCA, including:

- The latest trends in FCA enforcement actions and associated litigation affecting drug and device companies;

- Updates on the Trump Administration’s approach to FCA enforcement, including developments with the Yates Memo, guidance on cooperation credit in FCA cases, and DOJ’s use of its statutory dismissal authority;

- Notable legislative and administrative developments affecting the FCA’s statutory framework and application; and

- The latest developments in FCA case law, including recent Supreme Court jurisprudence and the continued evolution of how lower courts are interpreting the Supreme Court’s Escobar decision.

View Slides (PDF)

PANELISTS:

Stuart F. Delery is a partner in the Washington, D.C. office. He represents corporations and individuals in high-stakes litigation and investigations that involve the federal government across the spectrum of regulatory litigation and enforcement. Previously, as the Acting Associate Attorney General of the United States (the third-ranking position at the Department of Justice) and as Assistant Attorney General for the Civil Division, he supervised the DOJ’s enforcement efforts under the FCA, FIRREA and the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act.

Marian J. Lee is a partner in the Washington, D.C. office where she provides FDA regulatory and compliance counseling to life science and health care companies. She has significant experience advising clients on FDA regulatory strategy, risk management, and enforcement actions.

John D. W. Partridge is a partner in the Denver office where he focuses on white collar defense, internal investigations, regulatory inquiries, corporate compliance programs, and complex commercial litigation. He has particular experience with the False Claims Act and the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (“FCPA”), including advising major corporations regarding their compliance programs.

Jonathan M. Phillips is a partner in the Washington, D.C. office, where his practice focuses on FDA and health care compliance, enforcement, and litigation, as well as other government enforcement matters and related litigation. He has substantial experience representing pharmaceutical and medical device clients in investigations by the DOJ, FDA, and HHS OIG. Previously, he served as a Trial Attorney in DOJ’s Civil Division, Fraud Section, where he investigated and prosecuted allegations of fraud under the FCA and related statutes.

On October 9, 2019, the Department of the Treasury (“Treasury”) published proposed regulations on the transition from interbank offered rates (“IBORs”) to other reference rates (the “Proposed Regulations”).[1] A broad range of financial instruments are based on the London interbank offered rate (“LIBOR”). LIBOR, however, may be phased out after the end of 2021.[2] The Proposed Regulations address the tax consequences of the transition away from LIBOR in response to concerns raised by the Alternative Reference Rate Committee (“ARRC”).[3]

The ARRC’s overarching concern was that modifying a financial instrument to replace LIBOR with another reference rate (e.g., SOFR) might trigger adverse tax consequences for either the issuer or the holder. Without additional guidance, existing tax rules could potentially cause all holders of LIBOR-based instruments to realize gain or loss upon the replacement of LIBOR with another reference rate.[4]

To address the concerns of the ARRC regarding the adverse tax implications of modifying a financial instrument to replace LIBOR with an alternative reference rate and to provide much needed clarity, the Proposed Regulations provide that:

- Replacing LIBOR with another reference rate or adding a “fallback” provision (e.g., a provision stating that LIBOR will be replaced with another reference rate upon its elimination) to a financial instrument is not a realization event and will not cause recognition of gain or loss.

- Replacing LIBOR or adding a fallback provision will not cause recognition of gain or loss under the integrated transaction rules.

- Replacing LIBOR or adding a fallback provision will not cause recognition of gain or loss under the hedge accounting rules.

- A one-time payment made by one party to a financial instrument to another to account for any difference between LIBOR and the rate replacing it has the same character and source as other payments made by the same party with respect to the instrument.

- The existence of a fallback provision will not cause a debt instrument providing for a floating rate to be treated as a contingent payment debt instrument.

- Replacing LIBOR or adding a fallback provision in the organizational documents of a REMIC will not cause regular REMIC interests to be reclassified as residual interests.

The deadline to submit comments on the Proposed Regulations is November 25, 2019. Taxpayers can generally choose to apply the Proposed Regulations to modifications of debt instruments and non-debt instruments occurring after October 9, 2019, so long as they apply the Proposed Regulations consistently.[5]

1. Realization of Gain or Loss

Current tax rules provide that gain or loss is realized upon the exchange of property for other property that differs materially in kind or in extent (such an exchange is a “realization event”).[6] In the case of debt instruments, current tax rules also provide that a significant modification of the terms of an instrument is a realization event.[7] These rules further provide that the triggering of an existing “fallback” provision is not a significant modification,[8] since such a modification occurs by the operation of the existing terms of the instrument.[9] It is unclear, however, whether the addition of a fallback provision to an existing debt instrument or the outright substitution of another reference rate for LIBOR would constitute a significant modification.

The situation is even more uncertain in the case of non-debt instruments (e.g., derivatives), as current tax rules do not explain when modifications of such instruments constitute realization events and do not, a fortiori, provide that the triggering of an existing fallback provision is not a realization event. And just as in the case of debt instruments, it is unclear whether adding a fallback provision or substituting another reference rate for LIBOR in a non-debt instrument would be a realization event.

The Proposed Regulations significantly reduce the uncertainty as to which modifications of financial instruments constitute realization events. The Proposed Regulations provide that, for both debt instruments and non-debt instruments (including derivatives, stocks, insurance contracts, and lease agreements), neither the addition of a fallback provision nor the outright substitution of another reference rate for LIBOR is a realization event,[10] provided that the following conditions are satisfied:

- The new reference rate must be a “qualified rate.” Conveniently, Treasury provides a list of such rates, a list which includes SOFR.[11]

- The fair market value of the instrument after modification must be “substantially equivalent” to its fair market value before modification.[12] Thankfully, Treasury also provides two safe harbors under which this substantial equivalence condition is deemed satisfied.[13]

- The new reference rate must generally be based on transactions conducted in the same currency as the rate it replaces.[14] In the case of USD LIBOR, this means that the new reference rate must be based on transactions conducted in U.S. dollars, as is the case with SOFR.

The Proposed Regulations also provide that modifications of an instrument that are associated with the addition of a fallback provision or the substitution of another qualified rate for LIBOR are not realization events.[15] These modifications, however, are only covered to the extent they are reasonably necessary to effect the addition or substitution.[16] For example, the Proposed Regulations provide that modifying a financial instrument to add the obligation for one party to make a one-time payment to the other is not a realization event, so long as adding such an obligation is reasonably necessary to effect the replacement of LIBOR with another qualified rate.[17]

The Proposed Regulations also clarify that financial instruments that were issued before certain dates and are “grandfathered” under certain provisions of the Code, including sections 163(f), 871(m), and 1471, will not lose their grandfathered status as a result of the addition of a fallback provision or the substitution of another reference rate for LIBOR.[18]

2. Integrated Transactions

Issuers of debt instruments often enter into derivative contracts (e.g., interest rate swaps or credit default swaps) to hedge against risk. Under current tax rules, a hedge and the debt instrument to which it relates may be integrated and taxed as a single synthetic debt instrument (“SDI”), instead of being taxed as two separate instruments.[19] The rationale behind this rule is that, if the combined cash flows from a debt instrument and a hedge are substantially equivalent to the cash flows on a single debt instrument, then the debt instrument and its hedge should be taxed just as if they were such an instrument.[20]

The holder of an SDI “legs out” of an integrated transaction when it disposes of one (or both) of its components.[21] Legging out causes the integrated transaction to terminate and results in the holder of the defunct SDI being treated as having sold it for fair market value.[22] Absent further guidance, the addition of a fallback provision or the outright substitution of another reference rate for LIBOR in either components of an SDI may have caused a legging out resulting in realization of gain or loss.

The Proposed Regulations avoid this result and clarify that the amendment of any of the components of an integrated transaction to replace LIBOR with another reference rate is not a legging out, so long as the transaction, as modified, continues to qualify for integration.[23] Thus, an integrated transaction composed of a LIBOR-based debt instrument and interest rate swap is not terminated by reason of the substitution of SOFR for LIBOR in either the debt instrument or the swap.[24]

3. Hedge Accounting

Under current tax rules, taxpayers using the accrual method of accounting must account for hedging transactions in a way that clearly reflects income.[25] In other words, the method of accounting used must reasonably match the timing of income, deduction, gain, or loss from the hedging transaction with the timing of the income, deduction, gain, or loss of the items being hedged.[26] This general rule applies to hedges of debt instruments.[27]

Importantly, a taxpayer who retains a hedge while disposing of the items being hedged is required to match the built-in gain or loss in the former to the gain or loss realized on disposition of the latter.[28] A taxpayer can meet this requirement by marking the hedge to market on the date it disposes of the items being hedged.[29]

The Proposed Regulations provide that a modification of the terms of a debt instrument or derivative to replace LIBOR with another reference rate is not treated, for purposes of the hedge accounting rules, as a disposition or termination of either instrument.[30] This means that such a modification will not cause the taxpayer to realize gain or loss. The holder of a LIBOR-based debt instrument who enters into a LIBOR-based interest rate swap as a hedge, for instance, will not be required to mark either instrument to market upon the replacement of LIBOR with another reference rate in either.

4. One-Time Payments

The character of a one-time payment made by one party to a financial instrument to another party to account for the difference between the old rate and the new rate may be ambiguous. It is unclear, for instance, whether current tax rules would treat a one-time payment by a borrower to a lender in relation to the substitution of SOFR for LIBOR in a debt instrument as an interest payment or as a fee. Any ambiguity as to the character of a one-time payment implies an ambiguity as to whether it should be sourced to either the U.S. or another jurisdiction.

The Proposed Regulations provide that the character and source of a one-time payment made by a payor in connection with the addition of a fallback provision or the outright substitution of an another reference rate for LIBOR in a financial instrument are the same as the source and character that would otherwise apply to a payment by the same party with respect to the instrument.[31] As a result, a one-time payment by a borrower in relation to the substitution of SOFR for LIBOR in a debt instrument would indeed be treated as an interest payment and would therefore be sourced as such.[32]

5. Original Issue Discount and Qualified Floating Rates

Under current tax rules, debt instruments providing for a floating rate may be classified as either variable rate debt instruments (“VRDIs”) or contingent payment debt instruments (“CPDIs”). VRDIs generally benefit from an advantageous tax treatment compared to CPDIs. For instance, if a VRDI provides for stated interest that is unconditionally payable at least annually at a single qualified floating rate (“QFR”), then all of the stated interest on this VRDI is qualified stated interest.[33] This means that stated interest payments on such an instrument will not create original issue discount (“OID”).

In plain English, this means that the holder of a VRDI will not be required to include interest payments in income until it has received them (under its method of accounting).[34] By contrast, the holder of a CPDI may be required to include these payments in income before receiving them.[35]

The Proposed Regulations provide that, in the case of a debt instrument including a fallback provision, the LIBOR-based floating rate (provided it is a QFR) and the rate (e.g. a SOFR-based rate) that automatically replaces it upon the occurrence of a triggering event are treated as a single QFR.[36] Additionally, the Proposed Regulations state that the possibility that an IBOR—including LIBOR—will become unavailable is treated as a remote contingency and therefore will not cause a debt instrument containing a fallback provision to be classified as a CPDI.[37] Finally, the Proposed Regulations provide that the occurrence of an event triggering a fallback provision does not qualify as a change in circumstances and does not, as a result, cause the instrument to be treated as retired and reissued.[38] As a result, the triggering of a fallback provision does not cause a realization event.

6. REMICs

A real estate mortgage investment conduit (“REMIC”) is an entity formed for the purpose of holding a fixed pool of mortgages secured by interests in real property. REMICs issue both regular and residual interests. Under current tax rules, a regular interest in a REMIC is treated as a debt instrument.[39] Any REMIC interest that is not a regular interest is a residual interest.[40] The tax treatment of holders of regular interests is generally more advantageous than that of holders of residual interests.

For a REMIC interest to be a regular interest, the REMIC’s organizational documents must, on the startup day, irrevocably specify the interest rate (or rates) used to compute any interest payments on the regular interest.[41] The addition of a fallback provision to the terms of a REMIC’s organizational documents or the outright substitution of another reference rate for LIBOR would therefore cause all interests in this REMIC to be residual interests. Similarly, the possible triggering of an existing fallback provision by the elimination of LIBOR is treated by current tax rules as a contingency that prevents an interest in a REMIC from being a regular interest.[42]

In both cases, the Proposed Regulations provide relief to taxpayers. First, the Proposed Regulations explain that modifications of the terms of a REMIC’s organizational documents after the startup day to add a fallback provision or substitute another reference rate for LIBOR are disregarded for purposes of determining whether an interest in a REMIC is a regular interest.[43] Second, the Proposed Regulations state that the possibility that LIBOR will be replaced by another reference rate as the result of a fallback provision being triggered is not a contingency that will prevent a REMIC interest from being a regular interest.[44] The Proposed Regulations also provide that parties may agree to reduce the amounts of payments of principal or interest to account for the reasonable costs of replacing LIBOR with another reference rate without thereby jeopardizing the status of REMIC interests as “regular.”[45]

____________________

[1] Guidance on the Transition From Interbank Offered Rates to Other Reference Rates, 84 Fed. Reg. 54068 (Oct. 9, 2019).

[2] The UK Financial Conduct Authority (“UK FCA”) announced in 2017 that it would not compel or persuade banks to submit to LIBOR and that it would therefore not be necessary for the FCA to sustain LIBOR through its influence or legal powers. See The Future of LIBOR, Speech by Andrew Bailey, Chief Executive of the UK FCA (July 27, 2017), available at https://www.fca.org.uk/news/speeches/the-future-of-libor.

[3] The ARRC is a group of diverse private-market participants convened by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System and the Federal Reserve Bank of New York to help ensure successful transition from U.S. dollar (“USD”) LIBOR to the recommended alternative Secured Overnight Financing Rate (“SOFR”). More information on the ARRC is available at https://www.newyorkfed.org/arrc.

[4] See section 1001 of the Internal Revenue Code and § 1.1001–3(b) of the Treasury Regulations (discussed in detail below). Except where expressly stated otherwise, all section references are to the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, as amended (“I.R.C.”), and the Treasury Regulations (“Treas. Reg.”) promulgated thereunder.

[5] Proposed Treasury Regulations (“Prop. Treas. Reg.”) § 1.1001-6(g).

[6] Treas. Reg. § 1.1001–1(a).

[7] Treas. Reg. § 1.1001–3(b).

[8] Treas. Reg. § 1.1001–3(c)(1)(ii).

[10] Prop. Treas. Reg. § 1.1001-6(a)(1)-(3). Although the Proposed Regulations do not explicitly say so, they are naturally read as implying that the triggering of an existing fallback provision in a non-debt instrument is not a realization event.

[11] Prop. Treas. Reg. § 1.1001-6(b)(1)(i).

[12] Prop. Treas. Reg. § 1.1001–6(b)(2)(i).

[13] Prop. Treas. Reg. § 1.1001–6(b)(2)(ii).

[14] Prop. Treas. Reg. § 1.1001–6(b)(3).

[15] Prop. Treas. Reg. § 1.1001-6(a).

[16] Prop. Treas. Reg. § 1.1001-6(a)(5).

[18] Prop. Treas. Reg. § 1.1001-6(e).

[19] Treas. Reg. § 1.1275-6(a)

[21] Treas. Reg. § 1.1275-6(d)(2)(i)(A).

[22] Treas. Reg. § 1.1275-6(d)(2)(i)(B).

[23] Prop. Treas. Reg. § 1.1001-6(c).

[24] Id. See also 84 Fed. Reg. 54068, 54073 (Oct. 9, 2019). The Proposed Regulations provide similar rules for foreign currency hedges integrated with debt instruments under Treas. Reg. § 1.988–5(a) and interest rate hedges integrated with tax-exempt bonds under Treas. Reg. § 1.148–4(h).

[25] Treas. Reg. § 1.446-4(b).

[27] Treas. Reg. § 1.446-4(e)(4).

[28] Treas. Reg. § 1.446-4(e)(6).

[30] Prop. Treas. Reg. § 1.1001-6(c).

[31] Prop. Treas. Reg. § 1.1001-6(d).

[32] Although the proposed regulations do not address the case in which a lender makes a one-time payment to a borrower, Treasury has requested comments on the source and character of such a payment. 84 Fed. Reg. 54068, 54073.

[33] Treas. Reg. § 1.1275-5(e)(2)(i).

[34] Treas. Reg. § 1.1275-5(e).

[36] Prop. Treas. Reg. § 1.1275–2(m)(3).

[37] Prop. Treas. Reg. § 1.1275-2(m)(3).

[38] Prop. Treas. Reg. § 1.1275-2(m)(4), Treas. Reg. section 1.1275-2(h)(6).

[41] Treas. Reg. § 1.860G–1(a)(4)

[42] Treas. Reg. § 1.860G-1(b)(3).

[43] Prop. Treas. Reg. § 1.860G–1(e)(2).

[44] Prop. Treas. Reg. § 1.860G–1(e)(3). This rule applies so long as the LIBOR-based rate and the fallback rate are each rates permitted under I.R.C. § 860G.

[45] Prop. Treas. Reg. § 1.860G–1(e)(4).

Gibson Dunn’s lawyers are available to assist with any questions you may have regarding these developments. For further information, please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, any member of the firm’s Tax or Financial Institutions practice groups, or the following authors:

Jeffrey M. Trinklein – London/New York (+44 (0)20 7071 4224 /+1 212-351-2344), [email protected])

Jeffrey L. Steiner – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3632, [email protected])

Alexandre Marcellesi* – New York (+1 212-351-6222, [email protected])

Please also feel free to contact any of the following practice leaders and members:

Tax Group:

Jeffrey M. Trinklein – Co-Chair, London/New York (+44 (0)20 7071 4224 /+1 212-351-2344), [email protected])

Sandy Bhogal – London (+44 (0)20 7071 4266, [email protected])

Jérôme Delaurière – Paris (+33 (0)1 56 43 13 00, [email protected])

Hans Martin Schmid – Munich (+49 89 189 33 110, [email protected])

David Sinak – Co-Chair, Dallas (+1 214-698-3107, [email protected])

James Chenoweth – Houston (+1 346-718-6718, [email protected])

Brian W. Kniesly – New York (+1 212-351-2379, [email protected])

Eric B. Sloan – New York (+1 212-351-2340, [email protected])

Edward S. Wei – New York (+1 212-351-3925, [email protected])

Romina Weiss – New York (+1 212-351-3929, [email protected])

Benjamin Rippeon – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-955-8265, [email protected])

Daniel A. Zygielbaum – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3768, [email protected])

Dora Arash – Los Angeles (+1 213-229-7134, [email protected])

Paul S. Issler – Los Angeles (+1 213-229-7763, [email protected])

Scott Knutson – Orange County (+1 949-451-3961, [email protected])

Financial Institutions Group:

Matthew L. Biben – New York (+1 212-351-6300, [email protected])

Arthur S. Long – New York (+1 212-351-2426, [email protected])

Michael D. Bopp – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-955-8256, [email protected])

Jeffrey L. Steiner – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3632, [email protected])

* Mr. Marcellesi is not admitted to practice law in New York.

© 2019 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP

Attorney Advertising: The enclosed materials have been prepared for general informational purposes only and are not intended as legal advice.

Orange County partner Blaine Evanson and summer associates Raquel Sghiatti and Nicholas Barba are the authors of “The 2018 Supreme Court Term Belonged to the Chief Justice,” [PDF] published in the Orange County Lawyer in August 2019.

On September 1, 2019, Argentina introduced a number of new restrictions on foreign currency transactions, reversing its four-year-old policy that had eliminated such controls. This move follows similar recent capital restrictions imposed by other States. Such regulations may give rise to investment treaty claims by foreign investors.[1] In particular, depending on the circumstances, these measures may violate investors’ rights to (i) the free transfer of funds into and out of the host State; and (ii) fair and equitable treatment. Investors can directly enforce these rights against States via international arbitration.

Argentina and Other States Impose Currency Restrictions and Similar Measures

In the last few years, a number of States have imposed controls to stem capital outflows. In 2015, for example, Venezuela severely limited the permitted number of currency exchange transactions at the official rate and then set an artificially low Venezuelan bolivar to US dollar exchange rate. This significantly devalued the bolivar, wiping out billions of dollars of value held in monetary assets by multinational companies, while effectively preventing those companies from engaging in currency transactions to mitigate these losses.[2] In June 2019, Tanzania also restricted currency exchanges by imposing new, stricter regulations on foreign exchange bureaus and shutting down around a hundred of them.[3]

Most recently, last month, Argentina introduced currency restrictions that may detrimentally impact, among others, foreign companies that maintain investments in Argentina. On September 1, 2019, Argentina issued Decree 609/2019 announcing the new currency controls and mandating that Argentina’s central bank (Banco Central de la República Argentina or “BCRA”) establish the relevant guidelines and regulations.[4] Subsequently, the BCRA issued Communication “A” 6770, describing the specific exchange procedures to be implemented and how they will operate in practice.[5] The decree and BCRA communication, inter alia, require (i) exporters to convert foreign currency obtained into Argentine pesos; and (ii) both companies and individuals to obtain BCRA authorization before either purchasing foreign currency on the local foreign exchange market, or transferring funds abroad in certain situations.[6] Moreover, to access the local foreign exchange market, companies and individuals are now required to submit an affidavit detailing the nature of the relevant transactions and affirming compliance with the new rules.[7]

Additionally, the regulations require companies and other legal entities to obtain authorization from the BCRA before transferring dividends or profits abroad[8] or accessing the local currency exchange market for purchases of certain instruments.[9] These currency restrictions will remain in effect through December 31, 2019.

Such Measures May Violate Investment Protections

As explained in an earlier alert Gibson Dunn released in respect of the measures imposed by Venezuela in 2015,[10] the currency restrictions described above may violate obligations these States owe to foreign investors. In particular, many investment treaties contain a free transfer provision pursuant to which State Parties guarantee that investors from the other State Parties can freely transfer their investments and/or funds relating to that investment, typically without delays and at the exchange rate prevailing at the time of the transfer request. This includes investment treaties entered into by Venezuela, Argentina, and Tanzania. For example, the Argentina-US bilateral investment treaty provides at Article V that “[e]ach Party shall permit all transfers related to an investment to be made freely and without delay into and out of its territory.”[11] The Tanzania-UK bilateral investment treaty states at Article 6 that “[e]ach Contracting Party shall in respect of investments guarantee to nationals or companies of the other Contracting Party the unrestricted transfer of their investments and returns.”[12]

Arbitral tribunals have found that the free transfer guarantee is a “fundamental” and “essential element” of investment treaties,[13] and that currency control restrictions which “effectively imprison the investors’ funds” violate this guarantee.[14] Thus, if the measures introduced by Argentina and other States prevent a foreign investor from, inter alia, re-patriating profits earned from its investment, these States may have breached their free transfer obligations.

Moreover, many investment treaties (including those entered into by the States referenced above) oblige State Parties to treat investments of investors from the other State Parties fairly and equitably.[15] Tribunals have found that conduct that violates the free transfer guarantee may also breach the fair and equitable treatment standard.[16] Thus, there may be multiple bases upon which a foreign investor can hold these States accountable for damage such measures have caused to their investments.

* * *

Gibson Dunn lawyers have extensive experience advising clients on investment treaty arbitration, including in the context of currency restrictions and breaches of the free transfer guarantee contained in investment treaties. If you have any questions about how your company is impacted by capital controls or currency restrictions in markets where it is operating, we would be pleased to assist you.

__________________________

[1] States who are party to Bilateral Investment Treaties with Argentina include: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, China, Costa Rica, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Korea, Mexico, Netherlands, Panama, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Portugal, Russia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, U.K., U.S.A., and Vietnam.

[2] Gibson Dunn, Venezuela’s Currency Regulations May Violate Investment Treaty Protections, 25 February 2015, https://www.gibsondunn.com/venezuelas-currency-regulations-may-violate-investment-treaty-protections/.

[3] Reuters, Tanzania issues new rules to tighten foreign currency exchange controls, 25 June 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/tanzania-currency/tanzania-issues-new-rules-to-tighten-foreign-currency-exchange-controls-idUSL4N23W2KT.

[4] Presidencia de la Nación, “Mercado Cambiario – Deuda Pública,” Decreto No. 34.187, Boletín Oficial, 1 September 2019

[5] Banco Central de la República Argentina, “Exterior y Cambios. Adecuaciones,” Comunicación “A” 6770, 1 September 2019.

[9] These include debt instruments, investments, financial derivatives, loan grants to non-residents, deposits, currency hoarding, and transfers among residents. Id. at ¶ 5.

[10] Gibson Dunn, supra note 2.

[11] Argentina-U.S. BIT, Art. V.

[12] Tanzania-U.K. BIT, Art. 6.

[13] See Continental Casualty Company v. Argentine Republic, ICSID Case No. ARB/03/9, Award, 5 September 2008, ¶ 239.

[14] See Biwater Gauff (Tanzania) Limited v. United Republic of Tanzania, ICSID Case No. ARB/05/22, Award, 24 July 2008, ¶ 735.

[15] See, e.g., Argentina-U.S. BIT, Art. II(2) (“Investment shall at all times be accorded fair and equitable treatment, shall enjoy full protection and security and shall in no case be accorded treatment less than that required by international law.”); Tanzania-U.K. BIT, Art. 2(2) (“Investments of nationals or companies of each Contracting Party shall at all times be accorded fair and equitable treatment and shall enjoy full protection and security in the territory of the other Contracting Party.”).

[16] See AES Corporation and Tau Power B.V. v. Republic of Kazakhstan, ICSID Case No. ARB/10/16, Award, 1 November 2013, ¶ 425.

The following Gibson Dunn lawyers assisted in the preparation of this client update: Cyrus Benson, Penny Madden, Jeffrey Sullivan, Matthew McGill, Rahim Moloo, Charline Yim, Ankita Ritwik, Philip Shapiro and Sydney Sherman.

Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher’s lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding these issues. Please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, any member of the firm’s International Arbitration practice group, or the following:

Cyrus Benson – London (+44 (0) 20 7071 4239, [email protected])

Penny Madden – London (+44 (0) 20 7071 4226, [email protected])

Jeffrey Sullivan – London (+44 (0) 20 7071 4231, [email protected])

Matthew D. McGill – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3680, [email protected])

Rahim Moloo – New York (+1 212-351-2413, [email protected])

Charline O. Yim – New York (+1 212-351-2316, [email protected])

Ankita Ritwik – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3715, [email protected])

© 2019 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP

Attorney Advertising: The enclosed materials have been prepared for general informational purposes only and are not intended as legal advice.

With the California Consumer Privacy Act of 2018 (“CCPA”) set to take effect on January 1, 2020, California’s Attorney General Xavier Becerra released yesterday the much-anticipated draft regulations operationalizing the CCPA.[1] The CCPA (encoded in California Civil Code Sections 1798.100 to 1798.198), aims to give California consumers increased transparency and control over how companies use and share their personal information, and requires most businesses collecting information about California consumers to:

- disclose data collection, use, and sharing practices to consumers;

- delete consumer data upon request by the consumer;

- permit consumers to opt out of the sale or sharing of their personal information; and

- not sell personal information of consumers under the age of 16 without explicit consent.

As a reminder, the CCPA is a landmark privacy law with broad reach, that some have compared to Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Although the CCPA is California law, it applies to all entities doing business in California and collecting California consumers’ personal information if they meet certain thresholds, thereby impacting a wide range of companies. More information and our prior client alerts can be accessed here, including a summary of the CCPA and initial amendments to the CCPA.

Yesterday’s draft regulations flow from the law’s requirement that on or before January 1, 2020, the Office of the Attorney General (OAG) promulgate and adopt implementing regulations for the CCPA.[2] The attorney general is now accepting public comments on the draft regulations through December 6, 2019 and the OAG plans to hold four public hearings across California (Sacramento, Los Angeles, San Francisco and Fresno) in early December to collect additional feedback. If the OAG adheres to its previous guidance, we expect the final regulations to be promulgated 15 days following any changes to regulations, unless there are substantial changes, in which case another 45-day notice period will be triggered.[3] The attorney general’s power to enforce the law is delayed until either July 1, 2020 or six months after the final regulations are issued, whichever comes first. At this time, given the timeline for public comments, it appears that commencement of enforcement will likely be July 1, 2020, and definitely no earlier than mid-June.

To provide some context for the scope of the draft regulations, we briefly summarize below a number of the key requirements. However, this description is not exhaustive, and you should consult with your regular Gibson Dunn counsel to determine how these draft regulations may affect you and your company. As the public comment period is an important opportunity for companies handling consumer information to provide feedback on the draft regulations, please feel free to contact any of the Gibson Dunn attorneys listed below, all of whom would be happy to assist in the formulation of responses in advance of the December 6, 2019 deadline.

Notice to be Provided to Consumers

Keeping in tune with the theme of transparency to consumers, the draft regulations generally require any notices to be in “plain, straightforward language [that] avoid[s] technical or legal jargon,” visible and readable (including on small screens), available in the languages in which the business provides information, and accessible to consumers with difficulties. Businesses should keep in mind that this emphasis on accessibility to consumers has been the backbone of both the CCPA and the regulations. Hence, it will be important for notices and policies to be drafted in plain language for a general audience. More specifically, the draft regulations describe in some detail how companies should go about notifying consumers of: (1) their data rights at the point of collection (including for brick-and-mortar institutions, which had not expressly been considered by the text of the CCPA), (2) their ability to opt out of sale of personal information (the sample opt-out button or logo to be added in a modified version of the regulations[4]), (3) the financial incentive or price or service difference offered by allowing personal information to be used or sold, and (4) the business’s privacy policy (which needs to be available in an additional format that allows a consumer to print it out as a separate document, and available in whatever form makes sense for the collection of information).[5]

Process Requirements for Businesses and Consumers

The draft regulations further describe how businesses should procedurally handle consumer data requests, including requests to opt out of the sale of information and requests to delete information.[6] The draft regulations also specify how businesses should go about verifying consumers’ identities when they receive these data requests.[7] Notably, the regulations add further requirements, including that businesses must keep records of consumer requests for 24 months, and if a business buys, receives for commercial purposes, sells, or shares for commercial purposes personal information of 4 million or more consumers, the business is required to compile certain metrics and disclose them in the business’s privacy policy.[8] In addition, the regulations require businesses to at least provide a placeholder response within 10 days to consumer requests, even though substantive responses are not due for 45 days (or 90 days from the date of the request, should an extension be taken within the initial 45 days).[9] Businesses are required to support at least two methods for submitting requests. This includes, at a minimum, a toll-free telephone number and, if the business operates a website, an interactive webform accessible through the website or mobile application.[10] In other words, simply providing a contact email address in a privacy policy may not be sufficient (a webform will likely be required). Note, however, that the toll-free telephone number method may not be required if the pending legislation AB-1564 is signed into law.[11] The draft regulations require a two-step process for opt-ins following a previous decision to opt out, and online requests to delete: first, a request submission, and next a separate confirmation (which could be a new email, form, click etc.).[12]

Collection of Information Only From Sources Other than the Consumer

The draft regulations contain important information for businesses that obtain information from publicly available government sources and not directly from the consumers:

A business that does not collect information directly from consumers does not need to provide a notice at collection to the consumer, but before it can sell a consumer’s personal information, it shall do either of the following: (1) Contact the consumer directly to provide notice that the business sells personal information about the consumer and provide the consumer with a notice of right to opt-out in accordance with section 999.306; or (2) Contact the source of the personal information to: (a) Confirm that the source provided a notice at collection to the consumer in accordance with subsections a and b; and (b) Obtain signed attestations from the source describing how the source gave the notice at collection and including an example of the notice. Attestations shall be retained by the business for at least two years and made available to the consumer upon request.[13]

Interestingly, this seems to eliminate the need for data scrapers, or other businesses that are not obtaining information directly from the consumer, from providing notice at the time of collection from the consumer. However, the requirements for such businesses of providing notice or obtaining attestations when the data is sold may be burdensome. The draft regulations do not seem to anticipate obtaining information from non-government public sources, such as publicly available personal data from private websites on the Internet. Under those circumstances, it would seem that a business collecting from non-governmental sources (including posted publicly by the consumers themselves on social media or other sites), and then selling such information (under the broad definition of sale), may have to obtain attestations from companies and websites that host the data, and with whom the business likely has no relationship at all. If these regulations go into effect unchanged (e.g., without some form of identified safe harbor), the requirements for attestations may have a significant impact on data brokers that collect data from Internet sources.

Clarification of the Non-discrimination Requirement

There had been some speculation regarding how CCPA’s non-discrimination provision would be enforced (pursuant to Civil Code section 1798.125, a business is not allowed to treat a consumer differently because the consumer exercised a right conferred by the CCPA). The draft regulations, using examples, clarified that “a business may offer a price or service difference if it is reasonably related to the value of the consumer’s data as that term is defined in section 999.337.”[14] In other words, a business may charge a higher price to consumers who choose not to share their personal data, so long as the price differential is reasonably related to the “value of the customer’s data”. Section 999.337 provides eight methods, one or more of which can be used to calculate this value.

Conclusion

While the draft regulations have provided much-needed clarity to a number of process-related questions, several areas of uncertainty remain. Previously, the OAG had indicated that, in addition to what the regulations have addressed, they would also clarify or define (1) categories of personal information, (2) unique identifiers (things used to identify an entity connected to the internet), and (3) exceptions to the law (due to conflicts with state or federal laws, trade secrets, or other forms of intellectual property). However, the draft regulations do not appear to provide any significant guidance on such topics.

It is important to use the opportunity the OAG has provided for comments to weigh in on the issues that remain unclear. Companies currently undergoing compliance efforts for CCPA should continue to consider the additional insight gathered from these regulations, and we are available to assist with your inquiries as needed.

___________________________

[1] Press Release, Attorney General Becerra Publicly Releases Proposed Regulations under the California Consumer Privacy Act (October 10, 2019), available at https://oag.ca.gov/news/press-releases/attorney-general-becerra-publicly-releases-proposed-regulations-under-california. The entire text of the draft regulations is available at https://oag.ca.gov/sites/all/files/agweb/pdfs/privacy/ccpa-proposed-regs.pdf.

[2] Cal. Civ. Code § 1798.185(a)

[3] See https://oag.ca.gov/sites/all/files/agweb/pdfs/privacy/ccpa-public-forum-ppt.pdf

[4] Draft Regulations §999.306 (e).

[5] See Draft Regulations §999.305 (a)(2), §999.306 (a)(2), §999.307 (a)(2), §999.308 (a)(2).

[6] Draft Regulations §§ 999.312-315.

[7] Draft Regulations § 999.323.

[8] Draft Regulations § 999.317.

[9] Draft Regulations § 999.313.

[10] Draft Regulations § 999.312.

[11] AB-1564 is presently on Governor Newsom’s desk, awaiting final approval.

[12] Draft Regulations § 999.312(d), § 999.312(a).

[13] Draft Regulations § 999.305(d) (emphasis added).

[14] Draft Regulations § 999.336.

The following Gibson Dunn lawyers assisted in the preparation of this client update: Alex Southwell, Mark Lyon, Cassandra Gaedt-Sheckter, Arjun Rangrajan and Tony Bedel.

Gibson Dunn’s lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding these developments. Please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, or any member of the firm’s California Consumer Privacy Act Task Force or its Privacy, Cybersecurity and Consumer Protection practice group:

California Consumer Privacy Act Task Force:

Ryan T. Bergsieker – Denver (+1 303-298-5774, [email protected])

Cassandra L. Gaedt-Sheckter – Palo Alto (+1 650-849-5203, [email protected])

Joshua A. Jessen – Orange County/Palo Alto (+1 949-451-4114/+1 650-849-5375, [email protected])

H. Mark Lyon – Palo Alto (+1 650-849-5307, [email protected])

Arjun Rangrajan – Palo Alto (+1 650-849-5398, [email protected])

Alexander H. Southwell – New York (+1 212-351-3981, [email protected])

Deborah L. Stein (+1 213-229-7164, [email protected])

Eric D. Vandevelde – Los Angeles (+1 213-229-7186, [email protected])

Benjamin B. Wagner – Palo Alto (+1 650-849-5395, [email protected])

Please also feel free to contact any member of the Privacy, Cybersecurity and Consumer Protection practice group:

United States

Alexander H. Southwell – Co-Chair, PCCP Practice, New York (+1 212-351-3981, [email protected])

M. Sean Royall – Dallas (+1 214-698-3256, [email protected])

Debra Wong Yang – Los Angeles (+1 213-229-7472, [email protected])

Olivia Adendorff – Dallas (+1 214-698-3159, [email protected])

Matthew Benjamin – New York (+1 212-351-4079, [email protected])

Ryan T. Bergsieker – Denver (+1 303-298-5774, [email protected])

Richard H. Cunningham – Denver (+1 303-298-5752, [email protected])

Howard S. Hogan – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3640, [email protected])

Joshua A. Jessen – Orange County/Palo Alto (+1 949-451-4114/+1 650-849-5375, [email protected])

Kristin A. Linsley – San Francisco (+1 415-393-8395, [email protected])

H. Mark Lyon – Palo Alto (+1 650-849-5307, [email protected])

Karl G. Nelson – Dallas (+1 214-698-3203, [email protected])

Deborah L. Stein (+1 213-229-7164, [email protected])

Eric D. Vandevelde – Los Angeles (+1 213-229-7186, [email protected])

Benjamin B. Wagner – Palo Alto (+1 650-849-5395, [email protected])

Michael Li-Ming Wong – San Francisco/Palo Alto (+1 415-393-8333/+1 650-849-5393, [email protected])

Europe

Ahmed Baladi – Co-Chair, PCCP Practice, Paris (+33 (0)1 56 43 13 00, [email protected])

James A. Cox – London (+44 (0)20 7071 4250, [email protected])

Patrick Doris – London (+44 (0)20 7071 4276, [email protected])

Bernard Grinspan – Paris (+33 (0)1 56 43 13 00, [email protected])

Penny Madden – London (+44 (0)20 7071 4226, [email protected])

Michael Walther – Munich (+49 89 189 33-180, [email protected])

Kai Gesing – Munich (+49 89 189 33-180, [email protected])

Sarah Wazen – London (+44 (0)20 7071 4203, [email protected])

Vera Lukic – Paris (+33 (0)1 56 43 13 00, [email protected])

Alejandro Guerrero – Brussels (+32 2 554 7218, [email protected])

Asia

Kelly Austin – Hong Kong (+852 2214 3788, [email protected])

Jai S. Pathak – Singapore (+65 6507 3683, [email protected])

© 2019 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP

Attorney Advertising: The enclosed materials have been prepared for general informational purposes only and are not intended as legal advice.

On October 9, 2019, the Internal Revenue Service (“IRS”) released Rev. Rul. 2019-24, addressing two scenarios involving the taxation of virtual currencies. The ruling marks the first published guidance from the IRS in this area since 2014,[1] aside from the warning letters the IRS began sending to taxpayers in July 2019 to encourage voluntary compliance (Letter 6173, Letter 6174, and Letter 6174-A).

Rev. Rul. 2019-24 analyzes whether a taxpayer holding cryptocurrency recognizes gross income as a result of a “hard fork” and subsequent “airdrop” to the holder’s blockchain address.

A “hard fork” occurs when the there is a change in a cryptocurrency’s protocol that causes the blockchain to split into two: the “new” chain with the latest protocol and the old chain. Following a hard fork, holders of the forked cryptocurrency will generally receive an automatic distribution of the new cryptocurrency (commonly referred to as an “airdrop”). Importantly, an airdrop is automatic and provides each holder with access to an address for the holder’s pro rata share of the new cryptocurrency units, regardless of whether the holder has consented to the airdrop.

The two scenarios addressed by the ruling involve hard forks. In the first scenario (Situation 1), the taxpayer receives no airdrop following the hard fork, while the second scenario (Situation 2) includes an airdrop after the hard fork.

In Situation 1, the taxpayer holds units of one cryptocurrency and the protocol for that cryptocurrency experiences a hard fork, resulting in a new cryptocurrency. The taxpayer does not receive an airdrop or other transfer of the new cryptocurrency following the hard fork. The IRS concludes that the taxpayer does not have taxable income because the taxpayer did not “receive” units of the new cryptocurrency. For these purposes, the IRS defines “receipt” as the ability to “exercise dominion and control” over the virtual currency.[2] The IRS further notes that, where the address for cryptocurrency is held in a wallet managed through a cryptocurrency exchange and a hard fork with respect to the blockchain for that cryptocurrency creates a new cryptocurrency that is not supported by the exchange, the taxpayer will not be treated as having “dominion and control” over the new cryptocurrency.[3]

The IRS reached a different conclusion in Situation 2, which has a similar fact pattern as Situation 1, except that the taxpayer receives an airdrop of units of the new cryptocurrency after the hard fork that are immediately disposable. The IRS concludes that, because the taxpayer immediately has the ability to dispose of the new cryptocurrency, the taxpayer has “dominion and control” over it. Accordingly, the taxpayer is required to include in gross income the fair market value of the units as of the time that the airdrop is recorded on the blockchain.

Notably, the IRS did not address other virtual currency tax issues, such as the treatment of proof of stake protocols and “staking rewards.” The IRS also released a question and answer document alongside Rev. Rul. 2019-24, supplementing their reporting guidance from 2014 and incorporating the implications of this new ruling.

___________________

[1] Notice 2014-21, 2014-16 IRB 938.

[2] See Commissioner v. Glenshaw Glass Co., 348 U.S. 426, 431 (1955).

[3] However, the IRS noted that “dominion and control” could arise later if the taxpayer “acquires the ability to transfer, sell, exchange, or otherwise dispose of the [new] cryptocurrency.”

Gibson Dunn’s lawyers are available to assist with any questions you may have regarding these developments. For further information, please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, any member of the Tax Practice Group, or the following authors:

Brian R. Hamano* – San Francisco (+1 415-393-8350, [email protected])

James Chenoweth – Houston (+1 346-718-6718, [email protected])

Jeffrey L. Steiner – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3632, [email protected])

Please also feel free to contact any of the following leaders and members of the Tax group:

Jeffrey M. Trinklein – Co-Chair, London/New York (+44 (0)20 7071 4224 /+1 212-351-2344), [email protected])

David Sinak – Co-Chair, Dallas (+1 214-698-3107, [email protected])

James Chenoweth – Houston (+1 346-718-6718, [email protected])

Brian W. Kniesly – New York (+1 212-351-2379, [email protected])

Eric B. Sloan – New York (+1 212-351-2340, [email protected])

Edward S. Wei – New York (+1 212-351-3925, [email protected])

Romina Weiss – New York (+1 212-351-3929, [email protected])

Benjamin Rippeon – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-955-8265, [email protected])

Daniel A. Zygielbaum – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3768, [email protected])

Dora Arash – Los Angeles (+1 213-229-7134, [email protected])

Paul S. Issler – Los Angeles (+1 213-229-7763, [email protected])

Scott Knutson – Orange County (+1 949-451-3961, [email protected])

*Mr. Hamano is admitted only in New York and practicing under the supervision of Principals of the Firm.

© 2019 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP

Attorney Advertising: The enclosed materials have been prepared for general informational purposes only and are not intended as legal advice.

Orange County partner Blaine Evanson and Los Angeles associate Lauren Blas are the authors of “The First Monday,” [PDF] published in the Daily Journal on October 7, 2019.

Washington, D.C. partner Judith Alison Lee and associate R.L. Pratt are the authors of “Trump Administration Using a Variety of Measures to Target Chinese Tech Companies,” [PDF] published in Financier Worldwide in October 2019.

As the Supreme Court begins its 2019 Term, Gibson Dunn’s Supreme Court Round-Up provides summaries of the questions presented in the cases that the Court will hear this Term as well as other key developments on the Court’s docket. Gibson Dunn presented 3 oral arguments during the 2018 Term, and was involved in 12 additional cases as counsel for amici curiae. To date, the Court has granted certiorari in 44 cases for the 2019 Term, and Gibson Dunn is counsel for a party in 5 of those cases.

Spearheaded by former Solicitor General Theodore B. Olson, the Supreme Court Round-Up keeps clients apprised of the Court’s most recent actions. The Round-Up previews cases scheduled for argument, tracks the actions of the Office of the Solicitor General, and recaps recent opinions. The Round-Up provides a concise, substantive analysis of the Court’s actions. Its easy-to-use format allows the reader to identify what is on the Court’s docket at any given time, and to see what issues the Court will be taking up next. The Round-Up is the ideal resource for busy practitioners seeking an in-depth, timely, and objective report on the Court’s actions.

To view the Round-Up, click here.

Gibson Dunn has a longstanding, high-profile presence before the Supreme Court of the United States, appearing numerous times in the past decade in a variety of cases. During the Supreme Court’s 5 most recent Terms, 9 different Gibson Dunn partners have presented oral argument; the firm has argued a total of 13 cases in the Supreme Court during that period, including closely watched cases with far-reaching significance in intellectual property, separation of powers, and federalism. Moreover, although the grant rate for certiorari petitions is below 1%, Gibson Dunn’s certiorari petitions have captured the Court’s attention: Gibson Dunn has persuaded the Court to grant 28 certiorari petitions since 2006.

* * * *

Gibson Dunn’s lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding developments at the Supreme Court. Please feel free to contact the following attorneys in the firm’s Washington, D.C. office, or any member of the Appellate and Constitutional Law Practice Group.

Theodore B. Olson (+1 202.955.8500, [email protected])

Amir C. Tayrani (+1 202.887.3692, [email protected])

Jacob T. Spencer (+1 202.887.3792, [email protected])

Allison K. Turbiville (+1 202.887.3797, [email protected])

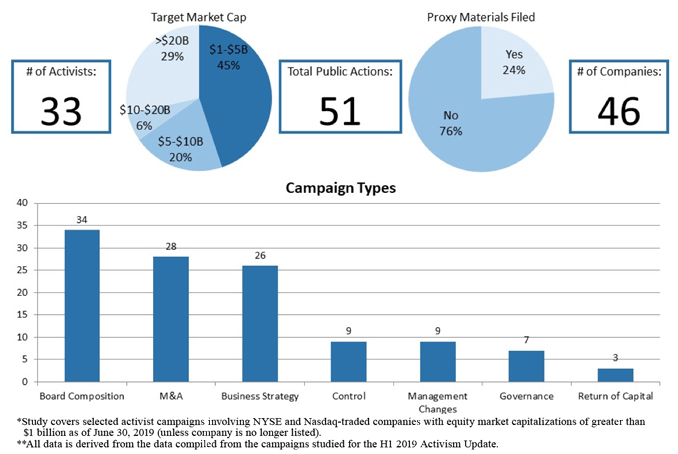

This Client Alert provides an update on shareholder activism activity involving NYSE- and Nasdaq-listed companies with equity market capitalizations in excess of $1 billion during the first half of 2019. As is typically the case during proxy season, shareholder activism rose during the first half of 2019 relative to the second half of 2018 as reflected in the number of public actions (51 vs. 40), in the number of activist investors that launched campaigns (33 vs. 29) and in the number of companies involved (46 vs. 34). As compared to the same period of 2018, however, shareholder activism activity declined, as reflected by the number of public actions in the first half of 2018 (51 vs. 62), the number of activist investors that launched campaigns (33 vs. 41) and the number of companies involved (46 vs. 54).

The types of companies targeted by shareholder activists changed in certain respects as well. During the second half of 2018, activists focused primarily on smaller public companies, as nearly two-thirds of those that were the subject of campaigns had market capitalizations of less than $5 billion and only 17% had market capitalizations in excess of $20 billion. By contrast, in the first half of 2019, companies with a capitalization of less than $5 billion represented only 45% of those targeted by activists, and companies with market capitalizations in excess of $20 billion comprised 29% of those companies targeted. The campaigns launched by NorthStar Asset Management against Alphabet and Facebook, Pershing Square against United Technologies Corporation and Starboard against Bristol-Myers Squibb and Appaloosa (all companies with market capitalizations in excess of $50 billion) stood in contrast with the second half of 2018, when comparatively few campaigns involving companies with market capitalizations in excess of $50 billion were launched.

By the Numbers – H1 2019 Public Activism Trends

Additional statistical analyses may be found in the complete Activism Update linked below.

The rationales for activist campaigns during the first half of 2019 remained consistent with that of the second half of 2018. In both cases, the leading campaign types were focused on board composition, mergers and acquisitions and business strategy. These three rationales collectively comprised approximately 75% of campaigns during both time periods, with other rationales (governance, return of capital, management changes and control) representing a small minority. The frequency with which activists engaged in proxy solicitation increased, however, from 15% of campaigns in the second half of 2018 to 24% of campaigns in the first half of 2019. (Note that the data provided in this Client Alert includes more campaign rationales than the number of campaigns, as certain activist campaigns had multiple rationales.)

A total of 17 settlement agreements were reached in the first half of 2019, and most maintained the key terms that have emerged as typical in recent years. Consistent with the second half of 2018, well over 90% of settlement agreements provided for voting agreements and standstill periods, and over 85% of settlement agreements included minimum and/or maximum share ownership levels and non-disparagement clauses. We delve further into the data and the details in the latter half of this edition of this Client Alert.

We hope you find this Client Alert informative. If you have any questions, please do not hesitate to reach out to a member of your Gibson Dunn team.

Gibson Dunn’s lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding the issues discussed in this publication. For further information, please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, or any of the following authors in the firm’s New York office:

Barbara L. Becker (+1 212.351.4062, [email protected])

Dennis J. Friedman (+1 212.351.3900, [email protected])

Richard J. Birns (+1 212.351.4032, [email protected])

Eduardo Gallardo (+1 212.351.3847, [email protected])

Saee Muzumdar (+1 212.351.3966, [email protected])

Daniel Alterbaum (+1 212.351.4084, [email protected])

Please also feel free to contact any of the following practice group leaders and members:

Mergers and Acquisitions Group:

Jeffrey A. Chapman – Dallas (+1 214.698.3120, [email protected])

Stephen I. Glover – Washington, D.C. (+1 202.955.8593, [email protected])

Jonathan K. Layne – Los Angeles (+1 310.552.8641, [email protected])

Securities Regulation and Corporate Governance Group:

Brian J. Lane – Washington, D.C. (+1 202.887.3646, [email protected])

Ronald O. Mueller – Washington, D.C. (+1 202.955.8671, [email protected])

James J. Moloney – Orange County, CA (+1 949.451.4343, [email protected])

Elizabeth Ising – Washington, D.C. (+1 202.955.8287, [email protected])

Lori Zyskowski – New York (+1 212.351.2309, [email protected])