Washington, D.C. partner F. Joseph Warin, San Francisco partner Winston Chan, Los Angeles associate Chris Jones and San Francisco associate Duncan Taylor are the authors of “Self-Reporting to the Authorities and Other Disclosure Obligations: The US Perspective” [PDF], Chapter 4 in The Practitioner’s Guide to Global Investigations 2023, Volume I: Global Investigations in the United Kingdom and the United States, Seventh Edition, published by Global Investigations Review in January 2023.

Each year we offer our observations on new developments and highlight select considerations for calendar-year filers as they prepare their Annual Reports on Form 10-K. This alert touches upon recent rulemaking from the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”), comments letters issued by the staff of the SEC’s Division of Corporation Finance (the “Staff”), and trends among reporting companies that have emerged throughout the last year.

An index of the topics described in this alert is provided below.

I. Trends in Human Capital Disclosure.

II. Trends in Climate Change Disclosure.

III. Disclosure Trends and Considerations Related to Macroeconomic Issues and Current Events.

A. Tailoring of COVID-19 Disclosure.

B. Increased Discussion of Geopolitical Conflict.

C. Expanded Disclosure of Supply Chain Disruptions and Mitigation Efforts.

D. More Detailed Discussion of Inflation Risks and Impacts.

E. Increased Discussion of Rising Interest Rates.

F. Inflation Reduction Act of 2022.

IV. Updated Staff Guidance on Non-GAAP Measures.

A. Question 100.01 – Misleading Adjustments.

B. Question 100.04 – Individually Tailored Accounting Principles.

C. Question 100.05 – Improper Labels and Descriptions.

D. Question 100.06 – Limits of Explanatory Disclosure.

E. Question 102.10 – Equal or Greater Prominence.

V. Cybersecurity Disclosure Considerations.

VII. Technical and Other Considerations.

A. New Filing Requirement for Glossy Annual Reports.

B. Clawback Check Boxes on Cover Page.

C. Item 201(e) Performance Graph and Pay-vs-Performance.

I. Trends in Human Capital Disclosure

Since 2021, companies have been required to include in their Form 10-K[1] a description of the company’s human capital resources, to the extent material to an understanding of the business taken as a whole, including the number of persons employed by the company, and any human capital measures or objectives that the company focuses on in managing the business (such as, depending on the nature of the company’s business and workforce, measures or objectives that address the development, attraction and retention of personnel).

The rule adopted by the SEC did not define “human capital” or elaborate on the expected content of the disclosures beyond the few examples provided in the rule text. This principles-based approach has resulted in significant variation among companies’ disclosures. With two years of human capital disclosure now available, we recently conducted a survey of the substance and form of human capital disclosures made by the S&P 100 in their Forms 10-K for their two most recently completed fiscal years. While company disclosures continued to vary widely, we saw companies generally expanding the length of their disclosures (79% of S&P 100 companies) and covering more topics (66% of S&P 100 companies), and also noted a slight increase in the amount of quantitative information provided in some areas. For a more detailed summary of our findings from this survey, please see our recently published client alert, “Evolving Human Capital Disclosures.”[2]

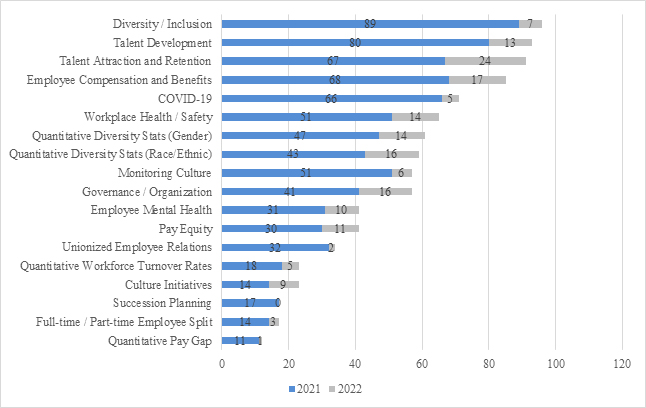

Our survey looked at seven primary categories of human capital disclosure, which were broken down further into 17 different disclosure topics.

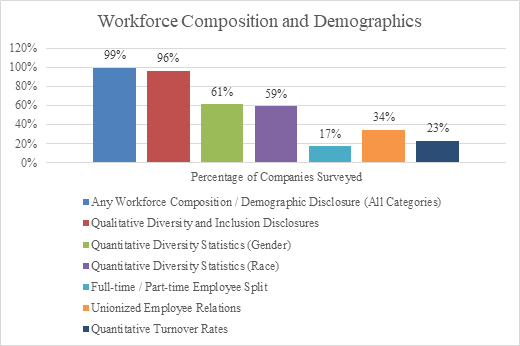

- Workforce Composition and Demographics. Nearly all S&P 100 companies discussed workforce composition and demographics to some degree. Diversity, equity, and inclusion continued to be the most common disclosure topics, with 96% of S&P 100 companies including a qualitative discussion of their commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion. The level of discussion ranged from generic statements expressing support of diversity in the workforce to detailed examples of actions taken to support underrepresented groups and increase representation in the workforce. Of S&P 100 companies, 61% included statistics related to gender representation and 59% included statistics related to racial representation (compared to 47% and 43% in the previous year, respectively). Most of these companies provided statistics for their workforce as a whole; however, an increased subset (37% in the most recent year, compared to 22% in the previous year) included separate statistics for different classes of employees and/or their boards of directors. We continue to see only a relatively small number of companies disclose full-time/part-time employee metrics (17% of the S&P 100) and workforce turnover rates (23% of the S&P 100).

- Recruiting, Training, Succession. Over 90% of S&P 100 companies discussed talent attraction, retention, and development. These were mostly qualitative disclosures discussing programs and benefits in place to recruit and maintain talent. There was no increase in the number of companies that covered succession planning.

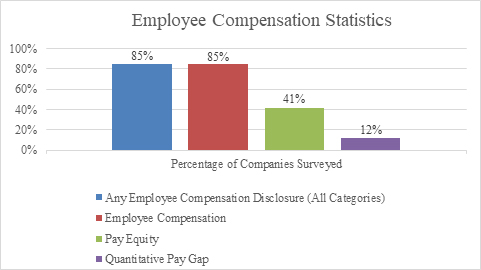

- Employee Compensation. Of companies surveyed, 85% included disclosure relating to employee compensation, generally providing a qualitative description of the compensation and benefits program offered to employees. Although 41% of companies surveyed included a discussion of pay equity practices in their 2021 Form 10-K (compared to 30% in 2021), quantitative measures of pay gaps based on gender or racial representation continued to be uncommon (12% of companies surveyed in 2022 compared to 11% in 2021).

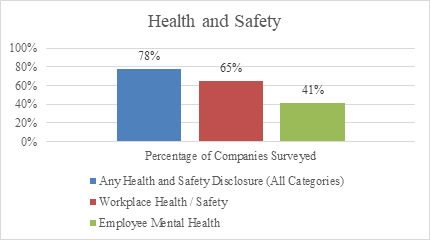

- Health and Safety. Of S&P 100 companies, 78% included disclosures relating to workplace health and safety. Disclosures primarily focused on the companies’ commitment to safety in the workplace and compliance with applicable regulatory and legal requirements, but quantitative disclosures on workplace safety, such as historical and/or target incident or safety rates, were uncommon (10% of companies surveyed in 2022).

- Culture and Engagement. Discussions on culture and engagement increased from the prior year, with a majority of S&P 100 companies explaining how they monitor culture and employee engagement. Some companies also included disclosures centered on practices and initiatives undertaken to build and maintain culture, including diversity-related and inclusion initiatives.

- COVID-19. Companies continued to include information regarding COVID-19 and its impact on company policies and procedures or on employees generally (71% of companies surveyed in 2022, compared to 66% in 2021). We expect that some companies may slim down their disclosure related to COVID-19 impacts in their next Form 10-K.

- Human Capital Management Governance and Organizational Practices. The percentage of S&P 100 companies discussing human capital management governance and/or organizational practices (such as oversight by the board of directors or a committee and the organization of the human resources function) increased from 41% in 2021 to 57% in 2022.

While we anticipate that human capital disclosure will continue to evolve under the existing principles-based requirements, per the SEC’s recently released Fall 2022 Regulatory Flexibility Agenda, we expect the SEC to propose more prescriptive rules in the first quarter of 2023 that will significantly change the landscape. SEC chair Gary Gensler has instructed the Staff “to propose recommendations for the Commission’s consideration on human capital disclosure…. This could include a number of metrics, such as workforce turnover, skills and development training, compensation, benefits, workforce demographics including diversity, and health and safety.”

II. Trends in Climate Change Disclosure

In March 2022, the SEC issued proposed rules on climate change disclosure requirements that, if adopted as proposed, will require disclosure of extensive and detailed climate-related information, including climate-related risks and opportunities, board oversight of climate-related risks, amount of greenhouse gas emissions, attestation of reporting on emissions, and a separate financial statement footnote on the impact of climate change. The proposed rules generated extensive positive and negative feedback from investors, companies, politicians, and others, and we believe it is unlikely that the SEC will adopt the rules as proposed. For a summary of the proposed climate change disclosure rules, please see our prior client alert, “Summary of and Considerations Regarding the SEC’s Proposed Rules on Climate Change Disclosure.”[3]

While there are no new SEC requirements on climate change disclosure that directly impact the 2022 Form 10-K, Form 10-K comment letters issued by the Staff over the past year underscore the Staff’s expectation of climate-related disclosures in response to existing requirements. The Staff initially issued a number of comment letters relating exclusively to climate-change disclosure issues in the fall of 2021. This was followed by the Staff publishing a sample comment letter related to climate-change disclosure issues on its website in September 2021.[4] Based on a review of comment letters issued in 2022, a growing trend we saw was the SEC asking for more quantification around climate-related disclosures. Resolution of comments often required more than one round of responses as the Staff honed in on a company’s analysis of whether a specific disclosure item was material.

The general focus of these climate-related comments fall under four general areas:

- The impact of climate legislation, regulation, and international accords. For example, the Staff has asked companies to disclose the risks they face as a result of climate-change legislation, regulation, or treaties to the extent such risks are reasonably likely to have a material effect on the company’s business, financial condition, and results of operations.

- The indirect consequences of climate-related regulation or business trends. For example, the Staff has asked for additional detail on indirect consequences, such as increased demand for goods that may produce lower emissions, increased competition to develop new products, and any anticipated reputational risks resulting from operations or services that produce material emissions.

- The physical effects of climate change. For example, the Staff has placed a particular emphasis on quantifying material weather-related damage to property, weather-related impacts on major customers and suppliers, and cost and availability of insurance.

- The material expenditures for climate-related projects and increase in compliance costs. For example, the Staff has requested quantification of any material past and/or future capital expenditures for climate-related projects for each of the periods for which financial statements are presented.

For companies reviewing their existing climate-related disclosures in their Form 10-K, a few items to consider in light of these Staff comments include:

- Tailor climate-related disclosures to the company’s business and financial condition, rather than generic discussions on climate change. For example, the Staff may ask a company to provide specific disclosure, if material, as to the impact on the company’s business of climate change risks disclosed in the risk factor section.

- Consider whether certain climate-related matters should be disclosed not only qualitatively, but also quantitatively. For example, if climate-related capital projects have become a significant portion of overall capital expenditures spending, the comment letters indicate that quantitative disclosure may be warranted.

- As part of the disclosure controls and procedures for the 2022 Form 10-K filing, review ESG materials publicly disclosed by the company, such as the company’s sustainability report, to determine whether any of the information in them is material under federal securities laws. Based on Staff comments, the Staff may look at these additional disclosures outside a company’s SEC filings and ask what consideration was given to including these disclosures in the Form 10-K. To the extent information disclosed in sustainability reports is not material for purposes of SEC rules, as we previously advised in our prior client alert, “Considerations for Climate Change Disclosures in SEC Reports,”[5] appropriate disclaimers to that effect should accompany such disclosures.

III. Disclosure Trends and Considerations Related to Macroeconomic Issues and Current Events

An increased Staff focus on current events and macroeconomic trends kicked off in 2020 as public companies began disclosing impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on their operations. At the time, the Staff issued CF Disclosure Guidance: Topic No. 9 (published March 25, 2020)[6] and CF Disclosure Guidance: Topic No. 9A (published June 23, 2020),[7] specifically regarding how companies should assess and disclose the impact of COVID-19; however, the guidance provides helpful instruction as companies evaluate the impact of other macroeconomic events, such as ongoing geopolitical conflicts, increased inflation, rising interest rates, and recessionary concerns. Below are a few general tips when drafting disclosure around current events and macroeconomic trends:

- Avoid generic disclosure of current events; be specific as to how these factors impact financial performance and operations.

- Avoid static disclosure of current events; update prior year disclosure to reflect impact during fiscal year 2022, as well as any known trends and uncertainties for 2023 and beyond.

- Confirm disclosure of current events and macroeconomic trends is consistent through the relevant parts of Form 10-K, such as the business section, risk factors, management’s discussion and analysis of financial condition and results of operations (“MD&A”), forward-looking statement disclaimer, and notes to the financial statements.

Set forth below are discussions of some of the major current events and macroeconomic trends that may impact a company’s disclosure in the upcoming Form 10-K.

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to impact public companies, though the direct and indirect impacts on a company’s operations or financial condition or on its industry may have changed significantly since the 2021 Form 10-K filing. As companies take a fresh look at their existing COVID-19 disclosure, discussions should be tailored to highlight actual impacts realized in 2022, and risk factors may need to be slimmed down to focus on the material risks that COVID-19 still presents. For some companies or select industries, discussion of COVID-19 as a trend or risk may still be a prominent disclosure for the 2022 Form 10-K, particularly for companies and industries whose supply chains continue to be impacted.

With the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine, public companies may need to discuss the conflict’s direct and indirect impacts on their operations and financial condition. In May 2022, the Staff published a “Sample Comment Letter Regarding Disclosures Pertaining to Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine and Related Supply Chain Issues.”[8] In the letter, the Staff emphasized that companies should provide detailed disclosure, to the extent material, regarding (i) direct or indirect exposure to Russia, Belarus, or Ukraine through operations or investments in such countries, securities trading in Russia, sanctions imposed or legal or regulatory uncertainty associated with operating in or existing in Russia or Belarus, (ii) direct or indirect reliance on goods or services sourced in Russia or Ukraine, (iii) actual or potential disruptions in the company’s supply chain, or (iv) business relationships, connections to, or assets in, Russia, Belarus, or Ukraine. Similar to Staff comment letters on climate-related disclosure, comment letters received by public companies in the fall of 2022 on the Russia-Ukraine conflict have requested more specific, including quantified, information on the impacts to the company’s operations and financial condition.

Companies should undertake similar disclosure analyses to determine whether direct or indirect impacts of emerging geopolitical conflicts, such as rising tensions between China and Taiwan, should be discussed in any sections of the upcoming Form 10-K.

C. Expanded Disclosure of Supply Chain Disruptions and Mitigation Efforts

In a somewhat related vein, companies experiencing supply chain difficulties should consider whether discussion of those issues in their risk factors and MD&A is sufficient. In comment letters recently issued to companies that mentioned supply chain disruptions, the Staff requested that the companies specify whether these challenges materially impacted the company’s results of operations or capital resources and quantify, to the extent possible, how the company’s sales, profits, and/or liquidity have been impacted. Several comment letters have also requested that companies discuss any known trends or uncertainties resulting from mitigation efforts undertaken and whether those efforts have introduced new material risks, including those related to product quality, reliability, or regulatory approval of products.

With the rise of inflation in 2022, companies should consider whether their disclosures regarding inflation impacts and risks are adequate. Depending on the effect on a company’s operations and financial condition, additional disclosure in risk factors, MD&A, or the financial statements may be necessary. In recent comment letters, the Staff has focused on how current inflationary pressures have materially impacted a company’s operations and sought disclosure on any mitigation efforts implemented with respect to inflation. If inflation is identified as a significant risk, the Staff requested companies to quantify, where possible, the extent to which revenues, expenses, profits, and capital resources were impacted by inflation.

For example, one company received the following comment: “We note your risk factor indicating that inflation can have an adverse impact on your business and on [y]our customers. Please update this risk factor if recent inflationary pressures have materially impacted your operations. In this regard, if applicable, discuss how your business has been materially affected by the various types of inflationary pressures you are facing” (emphasis added). Another company received this comment: “In various sections of your filings as well as earnings releases, you identify inflation as a significant risk you are experiencing, and indicate that there are various sources for the inflation you are experiencing. Please revise your future filings to discuss and quantify, where possible, the extent to which your revenues, expenses, profits, and capital resources have been impacted by inflation. Identify the drivers of inflation that most affected your options, and discuss your mitigation efforts. Provide us with your proposed disclosures in your response” (emphasis added).

In the current environment of relatively high interest rates, companies should also consider whether the recent rate increases and uncertainty regarding future rate changes are adequately discussed. In recent comment letters, the Staff has asked companies to expand their discussion of rising interest rates in the Risk Factors and MD&A sections to specifically identify the actual impact of recent rate increases on the business’s operations and how the business has been affected.

It is also critical that companies confirm that their disclosures in Item 7A (Quantitative and Qualitative Disclosures About Market Risk) are up-to-date and responsive to the requirements of Item 305 of Regulation S-K.

In August 2022, the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (the “Act”) was signed into law. One of the aspects of the Act was the introduction of a 1% excise tax on certain corporate stock buybacks. More specifically, the Act would impose a nondeductible 1% excise tax on the fair market value of certain stock that is “repurchased” during the taxable year by a publicly traded U.S. corporation or acquired by certain of its subsidiaries. The taxable amount is reduced by the fair market value of certain issuances of stock throughout the year. The Act also imposes a 15% corporate minimum tax and extends and expands tax incentives for clean energy. To the extent any provisions of the Act may impact a company’s business or financial condition, additional disclosure regarding the impact of the Act may need to be added to the risk factors, MD&A or the financial statements for the 2022 Form 10-K. For more information regarding the Act, please see our prior client alert, “Update: Senate Passes Revised Version of Inflation Reduction Act of 2022; Carried Interest Changes Omitted and Tax on Corporate Stock Buybacks Added.”[9]

IV. Updated Staff Guidance on Non-GAAP Measures

In 2022, the Staff, through comment letters issued during Form 10-K reviews, continued to focus on whether non-GAAP measures disclosed in periodic reports, earnings releases, and other earnings materials complied with Regulation G and Item 10(e) of Regulation S-K, as applicable. Issues emphasized in those comment letters include (i) whether certain performance measures should have been identified as non-GAAP measures, (ii) whether identified non-GAAP measures were presented with the most directly comparable GAAP measure at the appropriate prominence level, and (iii) the appropriateness of adjustments in non-GAAP measures. With respect to adjustments, care must be taken when deciding whether to adjust for current events, such as COVID-19 or the Russia-Ukraine conflict. Adjustments are typically only appropriate when they directly relate to a nonrecurring event and are clearly calculable and separable.

On December 13, 2022, the Staff announced an update to its Compliance and Disclosure Interpretations (“C&DI”) on Non-GAAP Financial Measures. Many of the changes memorialize positions taken by the Staff in recent comment letters or provide additional detail about those positions. A discussion of the significant changes is provided below, and a marked version of the impacted C&DIs is available in our prior post on the Gibson Dunn Securities Regulation and Corporate Governance Monitor, “SEC Updates Non-GAAP C&DIs.”[10]

Question 100.01 was revised to emphasize that a company’s individual facts and circumstances affect whether an adjustment makes a non-GAAP measure misleading. Using the pre-update example (i.e., a non-GAAP performance measure that excludes normal, recurring, cash operating expenses may be misleading), the updated C&DI illustrates this by noting that:

- When evaluating what is a “normal, operating expense,” the Staff considers the nature and effect of the non-GAAP adjustment and how it relates to the company’s operations, revenue generating activities, business strategy, industry, and regulatory environment.

- The Staff would view an operating expense that occurs repeatedly or occasionally, including at irregular intervals, as “recurring.”

B. Question 100.04 – Individually Tailored Accounting Principles

Question 100.04, which was completely rewritten, continues to include a prohibition on individually tailored accounting principles, but has now been supplemented with the following additional examples of adjustments that would run afoul of this prohibition:

- accelerating the recognition of revenue as though it was earned when customers were billed, when GAAP requires it to be recognized ratably over time;

- presenting revenue on a net basis when GAAP requires it to be presented on a gross basis (and vice versa); and

- changing the basis of accounting for revenue or expenses to a cash basis when GAAP requires it to be accounted for on an accrual basis.

New Question 100.05 memorializes the Staff’s position, often expressed through comment letters, that a non-GAAP measure can be misleading if it (or any adjustment made to the GAAP measure) is not appropriately labeled and clearly described. Three examples are provided of labels that would be misleading because they do not reflect the nature of the non-GAAP measure:

- a contribution margin that is calculated as GAAP revenue less certain expenses, labeled “net revenue”;

- a non-GAAP measure labeled the same as a GAAP line item or subtotal even though it is calculated differently than the similarly labeled GAAP measure, such as “Gross Profit” or “Sales”; and

- a non-GAAP measure labeled “pro forma” that does not meet the pro forma requirements in Article 11 of Regulation S-X.

New Question 100.06 explains that a non-GAAP measure could be so inherently misleading that even extensive, detailed disclosure about the nature and effect of each adjustment would not prevent it from being materially misleading. No examples are provided.

Question 102.10, which relates to the equal or greater prominence rule, was broken into subparts and supplemented with more detailed explanations and additional examples of disclosures that the Staff believes violate Item 10(e) of Regulation S-K, including the following situations:

- Ratios. When a ratio is calculated using a non-GAAP financial measure and the most directly comparable GAAP ratio is not presented with equal or greater prominence.

- Charts/tables/graphs. When charts, tables, or graphs of non-GAAP financial measures are used and charts, tables, or graphs of the comparable GAAP measures are not presented with equal or greater prominence.

- Reconciliations. When a reconciliation begins with the non-GAAP financial measure or appears to constitute a non-GAAP income statement.

- Non-GAAP Income Statements. When a non-GAAP income statement is presented, even if it is not a full income statement; “most of the line items and subtotals found in a GAAP income statement” is objectionable to the Staff.

V. Cybersecurity Disclosure Considerations

Cybersecurity risks and incidents continue to remain a focus for the SEC. In March 2022, the SEC proposed amendments to its existing rules to enhance and standardize disclosures regarding cybersecurity risk management, strategy, governance, and incident reporting by public companies. The proposed amendments would require, among other things, disclosure about (i) material cybersecurity incidents, (ii) a company’s policies and procedures to identify and manage cybersecurity risks, (iii) the board of directors’ oversight of cybersecurity risk, (iv) the board of directors’ cybersecurity expertise, and (v) management’s role and expertise in assessing and managing cybersecurity risk and implementing cybersecurity policies and procedures. For more information about the proposed rules, please see our prior client alert, “SEC Proposes Rules on Cybersecurity Disclosure.”[11]

While the final rules have not yet been adopted, companies should review their existing cybersecurity risk disclosure and confirm that their disclosure controls, particularly related to incident reporting, are sufficient. In addition, when considering disclosure, companies may want to be mindful of the October 2022 updates that Institutional Shareholder Services (“ISS”) made to its Governance QualityScore methodology, which added new factors on information security, including whether the company discloses its third-party information security risks and whether the company experienced a third-party information security breach.[12] We note that comments issued by the Staff in the fall of 2022 reflect a heighted focus on cyberattacks (both in terms of potential risks and actual incidents), particularly in light of the ongoing Russia-Ukraine conflict.

VI. Reminder Regarding Past Amendments to Financial and Business Disclosure Requirements in Regulation S-K

For calendar year-end reporting companies, the 2021 Form 10-K was the first Form 10-K incorporating the SEC’s amendments to certain financial and business disclosure requirements of Regulation S-K, including Item 303 for MD&A. Adopted in November 2020, these amendments generally emphasized a principles-based approach to disclosure and eliminated certain prescriptive disclosure requirements. While virtually all reporting companies took advantage of certain of these disclosure requirements in their 2021 Form 10-K, such as removing the selected financial data in Item 6, many companies did not make drastic changes to their existing disclosure and opted to retain other disclosures notwithstanding the eliminated mandates, such as the tabular disclosure of contractual obligations.

Recent comment letters show that the Staff continues to seek additional disclosures responsive to certain aspects of the Regulation S-K amendments, including the requirement to discuss underlying reasons for material changes in line items and the requirements regarding critical accounting estimates. For example, companies that cited multiple factors impacting their financial results in MD&A have been requested by the Staff to revise future disclosures to further describe material line item changes and the underlying reasons for such changes in both quantitative and qualitative terms, including the impact of offsetting factors. In addition, companies whose disclosure of critical accounting estimates did little more than repeat portions of their significant accounting policy disclosure were asked to revise future disclosures to explain why each critical accounting estimate is subject to uncertainty and, to the extent the information is material and reasonably available, how much each estimate and/or assumption has changed over a relevant period, and the sensitivity of the reported amounts to the material methods, assumptions and estimates underlying its calculation.

For more information about the amendments to Regulation S-K, see our prior post, “Summary Chart and Comparative Blackline Reflecting Recent Amendments to MD&A Requirements Now Available.”[13]

VII. Technical and Other Considerations

In June 2022, the SEC adopted amendments mandating that annual reports sent to shareholders pursuant to Exchange Act Rule 14a-3(c) (i.e., “glossy” annual reports) must also be submitted to the SEC in the electronic format in accordance with the EDGAR Filer Manual. The amendments supersede the Staff guidance provided in 2016 stating that the SEC would not object if companies post their glossy annual reports to security holders on their corporate websites for at least one year in lieu of furnishing paper copies to the SEC.

These annual reports will be in PDF format and filed using EDGAR Form Type ARS. One technical concern with submitting “glossy” annual reports through EDGAR is file size limitations. The “glossy” annual reports are typically larger files as compared to other EDGAR filings because they tend to contain extensive graphics. In the final rule, the SEC noted that electronic submission in PDF format of the glossy annual report should capture the graphics, styles of presentation, and prominence of disclosures (including text size, placement, color, and offset, as applicable) contained in the reports. Accordingly, companies should be mindful of the file size of their glossy annual report and conduct test runs in advance to make sure that EDGAR is able to handle the file size or evaluate whether the PDF file can be compressed.

As part of the final clawback rules adopted by the SEC on October 26, 2022, new checkboxes will be added to the cover pages of Forms 10-K, 20-F, and 40-F. Companies must indicate by check boxes on their annual reports whether the financial statements included in the filings reflect a correction of an error to previously issued financial statements and whether any such corrections are restatements that required a recovery analysis. The SEC’s adopting release noted that, “[p]articularly as it relates to ‘little r’ restatements which typically are not disclosed or reported as prominently as ‘Big R’ restatements, the check boxes provide greater transparency around such restatements and easier identification for investors of those that triggered a compensation recovery analysis.”

While the effective date for the SEC’s clawback rule is January 27, 2023, companies do not need to adopt a clawback policy until after the stock exchanges’ listing standards implementing the SEC rule are proposed, adopted, and become effective, which could be as late as November 28, 2023. In the meantime, it is not clear whether the SEC will require companies to include these checkboxes on the Form 10-K cover page. Each check box will constitute an inline XBRL element, so once EDGAR is set up to expect these new elements, it is possible that filings could get rejected unless the elements are included. (A similar issue cropped up last year for companies that tried to file their Form 10-K without tagging the independent auditor name, location, and/or PCAOB ID number.) As of this writing, the official Form 10-K available through the Forms List on the SEC website[14] has not been updated to include these new check boxes.

As a reminder, companies have the option of including the stock price performance graph required by Item 201(e) of Regulation S-K, which shows the company’s total shareholder return (TSR), in the Rule 14a-3 annual report to security holders (distributed in connection with the proxy statement) or the Form 10-K itself (assuming a “10-K wrap” is used to comply with Rule 14a-3). Beginning in this year’s proxy statements, companies will be required to provide disclosure that satisfies the new pay versus performance disclosures required by Regulation S-K Item 402(v). (For a summary of the final pay versus performance rules, please see our prior client alert, “SEC Releases Final Pay Versus Performance Rules.”)[15] These new disclosure requirements include comparisons to a peer group that may be the peer group identified in the Regulation S-K Item 201(e) performance graph. To the extent companies would like to use the Item 201(e) peer group in their pay versus performance disclosures, they will want to make sure the group identified in last year’s Form 10-K or Rule 14a-3 annual report is the one that they want to use for their initial pay versus performance disclosure in the proxy statement. If a company wants to use a different peer group in the 2022 Form 10-K (and the pay versus performance disclosure) than the one in last year’s performance graph, it will need to, per Regulation S-K Item 201(e)(4), “explain the reason(s) for this change and also compare the [company’s] total return with that of both the newly selected index and the index used in the immediately preceding fiscal year.”

__________________________

[1] See Modernization of Regulation S-K Items 101, 103, and 105, Release No. 33-10825 (August 26, 2020), available at https://www.sec.gov/rules/final/2020/33-10825.pdf.

[2] Available at https://www.gibsondunn.com/evolving-human-capital-disclosures.

[3] Available at https://www.gibsondunn.com/summary-of-and-considerations-regarding-the-sec-proposed-rules-on-climate-change-disclosure/.

[4] See Sample Letter to Companies Regarding Climate Change Disclosures (September 22, 2021), available at https://www.sec.gov/corpfin/sample-letter-climate-change-disclosures.

[5] Available at https://www.gibsondunn.com/considerations-for-climate-change-disclosures-in-sec-reports/.

[6] Available at https://www.sec.gov/corpfin/coronavirus-covid-19.

[7] Available at https://www.sec.gov/corpfin/covid-19-disclosure-considerations.

[8] See Sample Letter to Companies Regarding Disclosures Pertaining to Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine and Related Supply Chain Issues (May 3, 2021), available at https://www.sec.gov/corpfin/sample-letter-companies-pertaining-to-ukraine.

[9] Available at https://www.gibsondunn.com/update-senate-passes-revised-version-of-inflation-reduction-act-of-2022-carried-interest-changes-omitted-tax-on-corporate-stock-buybacks-added/.

[10] Available at https://www.securitiesregulationmonitor.com/Lists/Posts/Post.aspx?ID=468.

[11] Available at https://www.gibsondunn.com/sec-proposes-rules-on-cybersecurity-disclosure/.

[12] Interestingly, under the current QualityScore methodology, companies that disclose an immaterial information security breach in the last three years may see an improvement in their Audit & Risk Oversight score as a result of ISS’s preference for more, rather than less, disclosure of cyber incidents, even if immaterial.

[13] Available at https://www.securitiesregulationmonitor.com/Lists/Posts/Post.aspx?ID=432.

[14] Available at https://www.sec.gov/forms.

[15] Available at https://www.gibsondunn.com/sec-releases-final-pay-versus-performance-rules/.

The following Gibson Dunn attorneys assisted in preparing this client update: Justine Robinson, Mike Titera, David Korvin, and Thomas Kim.

Gibson Dunn’s lawyers are available to assist with any questions you may have regarding these issues. To learn more about these issues, please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work in the Securities Regulation and Corporate Governance and Capital Markets practice groups, or any of the following practice leaders and members:

Securities Regulation and Corporate Governance Group:

Elizabeth Ising – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-955-8287, [email protected])

James J. Moloney – Orange County, CA (+1 949-451-4343, [email protected])

Lori Zyskowski – New York, NY (+1 212-351-2309, [email protected])

Brian J. Lane – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3646, [email protected])

Ronald O. Mueller – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-955-8671, [email protected])

Thomas J. Kim – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3550, [email protected])

Michael A. Titera – Orange County, CA (+1 949-451-4365, [email protected])

Aaron Briggs – San Francisco, CA (+1 415-393-8297, [email protected])

Julia Lapitskaya – New York, NY (+1 212-351-2354, [email protected])

Capital Markets Group:

Andrew L. Fabens – New York, NY (+1 212-351-4034, [email protected])

Hillary H. Holmes – Houston, TX (+1 346-718-6602, [email protected])

Stewart L. McDowell – San Francisco, CA (+1 415-393-8322, [email protected])

Peter W. Wardle – Los Angeles, CA (+1 213-229-7242, [email protected])

© 2023 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP

Attorney Advertising: The enclosed materials have been prepared for general informational purposes only and are not intended as legal advice.

A Survey of Disclosures from the S&P 100 During the Two Years Following Adoption of the Securities and Exchange Commission Rule

Human capital resource disclosures by public companies have continued to be a focus since the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission adopted the new rules in 2020; not only for companies making the disclosures, but employees, investors, and other stakeholders reading them. This alert serves as an update to the alert we issued in 2021, “Discussing Human Capital: A Survey of the S&P 500’s Compliance with the New SEC Disclosure Requirement One Year After Adoption,” and reviews disclosure trends among S&P 100 companies, each of which has now included human capital disclosure in their past two annual reports on Form 10-K. This alert also provides practical considerations for companies as we head into 2023.

The overall takeaway from our survey, which categorized disclosures into 17 topic areas, was that companies are generally expanding the length of their disclosures, covering more topics, and including slightly more quantitative information in some areas. We note the following trends regarding the S&P 100 companies’ disclosures compared to the previous year:

- Seventy-nine companies increased the length of their disclosures, though the increases were generally modest.

- Sixty-six companies increased the number of topics covered.

- The prevalence of 16 topics increased and one remained the same.

- The most significant year-over-year increases in frequency involved the following topics: talent attraction and retention (67% to 91%), employee compensation (68% to 85%), quantitative diversity statistics on race/ethnicity (43% to 59%) and gender (47% to 61%), workplace health and safety (51% to 65%), and pay equity (30% to 41%).

- The only topic that did not see an increase in frequency was succession planning, which remained at 17%.

- Eight-five companies included more qualitative details in their disclosures compared to the previous year, including information relating to diversity, equity, and inclusion (“DEI”) initiatives and programs and the board’s role in overseeing human capital initiatives, although the depth of the additional detail provided varied greatly between companies.

- In this most recent year, DEI was discussed by 96% of companies (89% in the previous year), and 37% of companies (22% in the previous year) went beyond qualitative DEI information and disclosed quantitative data regarding the breakdown of DEI statistics by job type or level (executive level, etc.).

- Disclosure regarding the role of the board (or a human capital-focused committee) in overseeing human capital jumped to 44% of companies this most recent year from 26% the previous year.

- The topics most commonly discussed this most recent year generally remained consistent with the previous year. For example, DEI, talent development, talent attraction and retention, COVID-19, and employee compensation and benefits remained the five most frequently discussed topics, while succession planning, full-time/part-time employee split, quantitative pay gaps, culture initiatives, and quantitative workforce turnover rates continued to be the five least frequently covered topics.

- Within each industry, the trends that we saw in the previous year regarding the frequency of topics disclosed generally remained the same.

I. Background on the Requirements

On August 26, 2020, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (the “Commission”) voted three to two to approve amendments to Items 101, 103, and 105 of Regulation S-K, including the principles-based requirement to discuss a registrant’s human capital resources to the extent material to an understanding of the registrant’s business taken as a whole.[1] Specifically, public companies’ human capital disclosure must include “the number of persons employed by the registrant, and any human capital measures or objectives that the registrant focuses on in managing the business (such as, depending on the nature of the registrant’s business and workforce, measures or objectives that address the development, attraction and retention of personnel).” One dissenting commissioner criticized the amendment for failing to even require disclosure of “commonly kept metrics such as part time vs. full time workers, workforce expenses, turnover, and diversity.”[2]

As discussed below, following the change in presidential administration, the Commission has indicated that it plans to revisit the human capital disclosure requirements and potentially adopt more prescriptive rules in the future.[3]

While companies disclosures under the principles-based rules varied widely, our survey was able to introduce some comparability. The next two sections show the relevant data from our survey.[4]

II. Disclosure Topics

Our survey classifies human capital disclosures into 17 topics, each of which is listed in the following chart, along with the number of companies that discussed the topic in 2021 and the number of additional companies that discussed the topic in 2022. Each topic is described more fully in the sections following the chart.

A. Workforce Composition and Demographics

Of the 100 companies surveyed, 99 included disclosures relating to workforce composition and demographics in one or more of the following categories:

- Diversity and inclusion. This was the most common type of disclosure, with 96% of companies including a qualitative discussion regarding the company’s commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion, up slightly from 89% the previous year. The depth of these disclosures varied, ranging from generic statements expressing the company’s support of diversity in the workforce to detailed examples of actions taken to support underrepresented groups and increase the diversity of the company’s workforce. Many companies also included a quantitative breakdown of the gender or racial representation of the company’s workforce: 61% included statistics on gender and 59% included statistics on race (compared to 47% and 43% in the previous year, respectively). Most companies provided these statistics in relation to their workforce as a whole; however, an increased subset (37% in the most recent year compared to 22% in the previous year) included separate statistics for different classes of employees (e.g., managerial, vice president and above, etc.) and/or for their boards of directors. Some companies also included numerical goals for gender or racial representation—either in terms of overall representation, promotions, or hiring—even if they did not provide current workforce diversity statistics.

- Full-time/part-time employee split. While most companies provided the total number of full-time employees, only 17% of the companies surveyed included a quantitative breakdown of the number of full-time versus part-time employees the company employed, up only slightly from 14% the previous year. Similarly, we saw a number of companies that provided statistics on the number of seasonal employees and/or independent contractors or a breakdown of employees by geographical location.

- Unionized employee relations. Of the companies surveyed, 34% stated that some portion of their workforce was part of a union, works council, or similar collective bargaining agreement, up slightly from 32% the previous year.[5] These disclosures generally included a statement providing the company’s opinion on the quality of labor relations, and in many cases, disclosed the number of unionized employees.

- Quantitative workforce turnover rates. Although a majority of companies discussed employee turnover and the related topics of talent attraction and retention in a qualitative way (as discussed in Section II.B. below), only 23% of companies surveyed provided specific employee turnover rates (whether voluntary or involuntary), up slightly from 18% the previous year.

B. Recruiting, Training, Succession

Of the companies surveyed, 96% included disclosures relating to talent and succession planning in one or more of the following categories:

- Talent attraction and retention. These disclosures were generally qualitative and focused on efforts to recruit and retain qualified individuals. While providing general statements regarding recruiting and retaining talent were relatively common, with 91% of companies including this type of disclosure (compared to 67% in 2021), quantitative measures of retention, like workforce turnover rate, were uncommon, with less than 23% of companies disclosing such statistics (as noted above).

- Talent development. The most common type of disclosure in this area related to talent development, with 93% of companies including a qualitative discussion regarding employee training, learning, and development opportunities, up from 80% the previous year. This disclosure tended to focus on the workforce as a whole rather than specifically on senior management. Companies generally discussed training programs such as in-person and online courses, leadership development programs, mentoring opportunities, tuition assistance, and conferences, and a minority also disclosed the number of hours employees spent on learning and development.

- Succession planning. Only 17% of companies surveyed addressed their succession planning efforts (unchanged from 2021), which may be a function of succession being a focus area primarily for executives rather than the human capital resources of a company more broadly.

C. Employee Compensation

Of the companies surveyed, 85% included disclosures relating to employee compensation, up from 68% the previous year. All of those companies included a qualitative description of the compensation and benefits program offered to employees. Of the companies surveyed, 41% addressed pay equity practices or assessments (compared to 30% in 2021), and substantially fewer companies (12% of companies surveyed in 2022 and 11% in 2021) included quantitative measures of the pay gap between diverse and nondiverse employees or male and female employees.

D. Health and Safety

Of the companies surveyed, 78% included disclosures relating to health and safety in one or both of the following categories:

- Workplace health and safety. Of the companies surveyed, 65% included qualitative disclosures relating to workplace health and safety, up from 51% in the previous year, typically with statements around the company’s commitment to safety in the workplace generally and compliance with applicable regulatory and legal requirements. However, 10% of companies surveyed provided quantitative disclosures in this category, generally focusing on historical and/or target incident or safety rates or investments in safety programs. These disclosures tended to be more prevalent among industrial and manufacturing companies. Many companies also provided disclosures on safety initiatives undertaken in connection with COVID-19, which is discussed separately below.

- Employee mental health. In connection with disclosures about standard benefits provided to employees, or additional benefits provided as a result of the pandemic, 41% of companies disclosed initiatives taken to support employees’ mental or emotional health and wellbeing, up from 31% the prior year.

E. Culture and Engagement

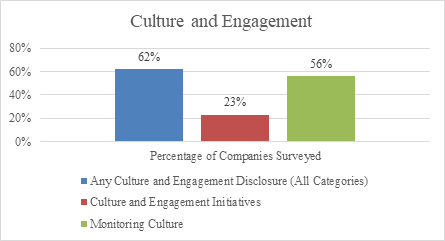

In addition to the many instances where companies mentioned a general commitment to culture and values, 62% of the companies surveyed discussed specific initiatives they were taking related to culture and engagement in one or more of the following categories:

- Culture and engagement initiatives. Of the companies surveyed, 23% included specific disclosures relating to practices and initiatives undertaken to build and maintain their culture and values, up from 14% in the previous year. These companies most commonly discussed efforts to communicate with employees (e.g., through town halls, CEO outreach, trainings, or conferences and presentations) and to recognize employee contributions (e.g., awards programs and individualized feedback). Many companies also discussed culture in the context of diversity-related initiatives to help foster an inclusive culture.

- Monitoring culture. Disclosures about the ways that companies monitor culture and employee engagement were much more common, with 56% of companies providing such disclosure, up from 51% the previous year. Companies generally disclosed the frequency of employee surveys used to track employee engagement and satisfaction, with some reporting on the results of these surveys, sometimes measured against prior year results or industry benchmarks.

F. COVID-19

A majority of companies (71% of those surveyed compared to 66% in 2021) included information regarding COVID-19 and its impact on company policies and procedures or on employees generally. COVID-19-related topics addressed ranged from work-from-home arrangements and safety protocols taken for employees who worked in person to additional benefits and compensation paid to employees as a result of the pandemic and contributions made to organizations supporting those affected by the pandemic.

G. Human Capital Management Governance and Organizational Practices

Over half of the companies (57% of those surveyed compared to 41% in 2021) addressed their governance and organizational practices (such as oversight by the board of directors or a committee and the organization of the human resources function).

III. Industry Trends

One of the main rationales underlying the adoption of principles-based—rather than prescriptive—requirements for human capital disclosures is that the relative significance of various human capital measures and objectives varies by industry. This is reflected in the following industry trends that we observed:[6]

- Technology Industries (E-Commerce, Internet Media & Services, Hardware, Software & IT Services and Semiconductors). For the 20 companies in the Technology Industries, 90% discussed talent development and training opportunities, talent attraction, recruitment and retention, employee compensation, and diversity. Relatively uncommon disclosures among this group included part-time and full-time employee statistics (10%), culture initiatives (15%), succession planning (10%), and quantitative pay gap (10%).

- Finance Industries (Asset Management & Custody Activities, Consumer Finance, Commercial Banks and Investment Banking & Brokerage). For the 13 companies in the Finance Industries, a large majority included quantitative diversity statistics regarding race (85%) and gender (85%). The same number of companies also included qualitative disclosures regarding employee compensation (85%), and, compared to other industries discussed below, a relatively higher number discussed pay equity (62%) and quantified their pay gap (38%). Relatively uncommon disclosures among this group included part-time and full-time employee statistics, unionized employee relations, quantitative workforce turnover rates, and succession planning (in each case less than 16%).

IV. Disclosure Format

The format of human capital disclosures in companies’ annual reports continued to vary greatly.

Word Count. The length of the disclosures ranged from 109 to 1,995 words, with the average disclosure consisting of 960 words and the median disclosure consisting of 949 words. Compare this to 2021, which saw a range of 105 to 1,931 words, with an average of 823 words and median of 818 words.

Metrics. While the disclosure requirement specifically asks for a description of “any human capital measures or objectives that the registrant focuses on in managing the business” (emphasis added), our survey revealed that 25% of companies determined not to include disclosure in any of the quantitative categories we discuss above, and 10% did not include any type of quantitative metrics in their disclosure beyond headcount numbers (down from 36% and 14%, respectively, in 2021). Given the materiality threshold included in the requirement and the fact that it is focused on what is actually used to manage the business, this is not a surprising result. It was common to see companies identify important objectives they focus on, but omit quantitative metrics related to those objectives; however, that group has been shrinking as more companies include metrics. For example, while 96% of companies discussed their commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion (compared to 89% in 2021), only 61% and 59% of companies disclosed quantitative metrics regarding gender and racial diversity, respectively (compared to 47% and 43%, respectively, in 2021).

Graphics. Although the minority practice, 24% of companies surveyed also included charts or other graphics, up from 21% the previous year, which were generally used to present statistical data, such as diversity statistics or breakdowns of the number of employees by geographic location.

Categories. Most companies organized their disclosures by categories similar to those discussed above and included headings to define the types of disclosures presented.

V. Comment Letter Correspondence

Comment letter correspondence from the staff of the Division of Corporation Finance (the “Staff”), which often helps put a finer point on principles-based disclosure requirements like this one, has shed relatively little light on how the Staff believes the new requirements should be interpreted. Consistent with what we found at this time last year, the comment letters, all of which involved reviews of registration statements, were generally issued to companies whose disclosures about employees were limited to the bare-bones items companies have discussed historically, such as the number of persons employed and the quality of employee relations. From these companies, the Staff simply sought a more detailed discussion of the company’s human capital resources, including any human capital measures or objectives upon which the company focuses in managing its business. There were also a few comment letters where the Staff asked companies to clarify statements in their human capital disclosures. Based on our review of the responses to those comment letters, we have not seen a company take the position that a discussion of human capital resources was immaterial and therefore unnecessary.

VI. Conclusion

During the most recent year, we generally saw companies expanding the length of their human capital disclosures, covering more topics, and including slightly more quantitative information in some areas; however, the principles-based nature of the disclosure requirements has continued to result in companies providing a wide variety of disclosures, with significant differences in depth and breadth.

Given how high the Human Capital Management Disclosure rulemaking appears on the Fall 2022 Reg Flex Agenda (it appears as an action item for the first quarter of 2023), it seems unlikely we will see another year pass without more prescriptive rules being proposed and possibly adopted.

There has been no shortage of investors, politicians, and activists chiming in with input on the forthcoming rules. For example, earlier this year, several members of Congress wrote a letter asking the Commission to resist requests for more specific and quantitative disclosures on human capital, which expressed particular concerns about requiring metrics on full-time employees, part-time employees, independent contractors, subcontractors, or contingent employees.[7] In June 2022, the Working Group on Human Capital Accounting Disclosure, a group composed of academics and former SEC officials, submitted a rulemaking petition requesting the Commission to require more financial information about human capital in companies’ disclosures.[8]

Until the Commission proposes and adopts new rules governing the disclosure of human capital management, however, we expect the wide variance in Form 10-K human capital disclosures to continue. As companies prepare for the upcoming Form 10-K reporting season, they should consider the following:

- Confirming (or reconfirming) that the company’s disclosure controls and procedures support the statements made in human capital disclosures and that the human capital disclosures included in the Form 10-K remain appropriate and relevant. In this regard, companies may want to compare their own disclosures against what their industry peers did these past two years, including specifically any notable additional disclosures made in the past year.

- Setting expectations internally that these disclosures likely will evolve. As shown by the measurable increase in disclosure in the second year of reporting, companies should expect to develop their disclosure over the course of the next couple of annual reports in response to peer practices, regulatory changes, and investor expectations, as appropriate. The types of disclosures that are material to each company may also change in response to current events.

- Addressing in the upcoming disclosure, if not already disclosed, the progress that management has made with respect to any significant objectives it has set regarding its human capital resources as investors are likely to focus on year-over-year changes and the company’s performance versus stated goals.

- Addressing significant areas of focus highlighted in engagement meetings with investors and other stakeholders. In a 2021 survey, 64% of institutional investors surveyed cited human capital management as a key issue when engaging with boards (second only to climate change at 85%).[9]

- Revalidating the methodology for calculating quantitative metrics and assessing consistency with the prior year. Former Chairman Clayton commented that he would expect companies to “maintain metric definitions constant from period to period or to disclose prominently any changes to the metrics.”

__________________________

[1] See 17 C.F.R. § 229.101(c)(2)(ii).

[2] See Regulation S-K and ESG Disclosures: An Unsustainable Silence, available at https://www.sec.gov/news/public-statement/lee-regulation-s-k-2020-08-26.

[3] Commission Chair Gary Gensler’s Fall 2022 Unified Agenda of Regulatory and Deregulatory Actions (the “Fall 2022 Reg Flex Agenda”) shows “Human Capital Management Disclosure” as being in the proposed rule stage. Available at https://www.reginfo.gov/public/do/eAgendaMain?operation=OPERATION_GET_AGENCY_RULE_LIST¤tPub=true&agencyCode&showStage=active&agencyCd=3235.

[4] Note that companies often include additional human capital management-related disclosures in their ESG/sustainability/social responsibility reports and websites and sometimes in the proxy statement, but these disclosures are outside the scope of the survey.

[5] While never expressly required by Regulation S-K, as a result of disclosure review comments issued by the Division of Corporation Finance over the years and a decades-old and since-deleted requirement in Form 1-A, it has been a relatively common practice to discuss collective bargaining and employee relations in the Form 10-K or in an IPO Form S-1, particularly since the threat of a workforce strike could be material.

[6] For purposes of our survey, we grouped companies in similar industries based on both their four-digit Standard Industrial Classification code and their designated industry within the Sustainable Industry Classification System. The industry groups discussed in this section cover 33% of the companies included in our survey.

[7] Available at https://www.warner.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/2022/2/warner-brown-call-on-sec-to-update-human-capital-disclosures-so-that-companies-report-the-number-of-employees-who-are-not-full-time-workers.

[8] Available at https://www.sec.gov/rules/petitions/2022/petn4-787.pdf.

[9] See Morrow Sodali 2021 Institutional Investor Survey, available at https://morrowsodali.com/insights/institutional-investor-survey-2021.

The following Gibson Dunn attorneys assisted in preparing this update: Meghan Sherley and Mike Titera.

Gibson Dunn’s lawyers are available to assist with any questions you may have regarding these issues. To learn more about these issues, please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work in the Securities Regulation and Corporate Governance practice group, or any of the following practice leaders and members:

Securities Regulation and Corporate Governance Group:

Elizabeth Ising – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-955-8287, [email protected])

James J. Moloney – Orange County, CA (+1 949-451-4343, [email protected])

Lori Zyskowski – New York, NY (+1 212-351-2309, [email protected])

Brian J. Lane – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3646, [email protected])

Ronald O. Mueller – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-955-8671, [email protected])

Thomas J. Kim – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3550, [email protected])

Michael A. Titera – Orange County, CA (+1 949-451-4365, [email protected])

Aaron Briggs – San Francisco, CA (+1 415-393-8297, [email protected])

Julia Lapitskaya – New York, NY (+1 212-351-2354, [email protected])

Labor and Employment Group:

Jason C. Schwartz – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-955-8242, [email protected])

Katherine V.A. Smith – Los Angeles (+1 213-229-7107, [email protected])

© 2023 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP

Attorney Advertising: The enclosed materials have been prepared for general informational purposes only and are not intended as legal advice.

On December 27, 2022, the Internal Revenue Service (the “IRS”) and the Department of the Treasury (“Treasury”) issued Notice 2023-7 (the “Notice”) to provide important interim guidance on the new corporate alternative minimum tax (the “CAMT”) enacted under the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022.[1] The Notice describes forthcoming regulations that are expected to be consistent with the interim guidance provided in the Notice and retroactive to January 1, 2023 (the date that the CAMT became effective). Taxpayers may rely on the interim guidance until the proposed regulations are issued. Accordingly, we expect this guidance to inform Q1 2023 estimated tax payments and financial reporting for affected taxpayers.

The Notice provides necessary and welcome guidance in many respects, but there remain significant open issues.

The Statute

For taxable years beginning after December 31, 2022, the CAMT requires certain corporations (each, an “Applicable Corporation”) to pay U.S. federal income tax on their adjusted financial statement income (“AFSI”) at a rate of at least 15 percent.[2] A corporation is an Applicable Corporation if it — together with the other members of its controlled group — averages more than $1 billion of AFSI over a three-year testing period. For a U.S. subsidiary of a foreign-parented multinational group to be an Applicable Corporation, the subsidiary also must have AFSI of $100 million or more over the same three-year testing period (taking into account the AFSI only of the domestic members of the group and the “effectively connected” AFSI of each foreign member), with certain adjustments.[3]

Key Provisions of the Notice

The Notice provides a safe harbor for determining whether a corporation will constitute an Applicable Corporation for the corporation’s first taxable year beginning after December 31, 2022. In addition, the Notice includes interim guidance regarding (i) a safe harbor for determining Applicable Corporation status and certain rules relating to controlled groups, (ii) how certain acquisitive and divisive transactions are taken into account, (iii) the calculation of AFSI for certain distressed corporations, and (iv) the treatment of depreciable property and certain tax credits for purposes of calculating AFSI. Below is a high-level summary of the key provisions of the Notice.

1. Applicable Corporation Determination – Safe Harbor and Certain Group Rule

a. Safe Harbor

For purposes of calculating AFSI to determine Applicable Corporation status, the statute requires a number of complex adjustments to the income or loss reported on a corporation’s financial statements. To simplify this determination, the Notice includes a safe harbor that allows a corporation, for its first taxable year beginning after December 31, 2022, to disregard the numerous adjustments required by the statute. Under the safe harbor, the corporation can simply use the income or loss reported on the corporation’s consolidated financial statements, with limited adjustments, but must apply a reduced AFSI threshold of $500 million (or $50 million in the case of a U.S. corporate subsidiary of a foreign-parented multinational group).

For corporations that are under the $500 million AFSI threshold of the safe harbor, the safe harbor simplifies what otherwise could be a burdensome (and time-sensitive, given upcoming estimated tax payments) determination. Note that if a corporation does not satisfy the safe harbor, it can still avoid being an Applicable Corporation under the statutory computational and threshold rules.

b. Consolidated Groups, Corporate Partners, and Foreign-Parented Multinational Groups

The application of the CAMT to consolidated groups, partnerships, and multinational corporations is of critical importance. The Notice clarifies some aspects of these rules but leaves open several questions.

- Single-entity treatment for consolidated groups. The Notice provides that a consolidated group is treated as a single entity for purposes of computing AFSI—both for determining Applicable Corporation status as well as for calculating CAMT liability.[4]

- Corporate partners – manner of taking into account partnership AFSI to determine Applicable Corporation status. Section 56(c)(2)(D)(i) contains a “distributive share” rule that provides that, for purposes of calculating AFSI to determine an Applicable Corporation’s CAMT liability, an Applicable Corporation that is a partner in a partnership takes into account only its distributive share of the partnership’s AFSI.[5] The Notice clarifies that the distributive share rule is disregarded for purposes of determining whether a corporation is an Applicable Corporation regardless of whether the partnership is part of the corporate partner’s controlled group.[6] The Notice does not provide any guidance regarding how a taxpayer should determine its distributive share. The IRS and Treasury have requested comments on the application of this distributive share rule.

- Foreign-parented multinational groups. The Notice addresses how the safe harbor applies to entities in a foreign-parented multinational group and also seeks comments in this area.

Although the determination of Applicable Corporation status in the context of investment fund structures involving partnerships and portfolio companies similarly raises significant issues, the Notice does not address any of these issues.[7]

2. Certain M&A and Restructuring Transactions – Combinations and Divisions

The Notice addresses how M&A and restructuring transactions affect the determination of Applicable Corporation status and the computation of CAMT liability.

a. Entirely Tax-free transactions disregarded

The Notice provides that any financial accounting gain or loss resulting from specified tax-free transactions is disregarded for purposes of calculating AFSI — both to determine Applicable Corporation Status and to calculate CAMT liability for the taxable years in which the applicable financial statements take into account the relevant nonrecognition transaction.[8] This guidance is particularly welcome in clarifying that both spin-offs and split-offs do not affect AFSI if they are otherwise tax-free even though split-offs can result in financial statement gain or loss. It is important to note that this rule applies only to transactions that are wholly tax-free (i.e., that do not have any “boot”).[9] The IRS and Treasury have requested comments regarding how to treat transactions that are partially taxable.

In addition, the Notice requires that each component transaction of a larger transaction be examined separately for qualification as a tax-free transaction that is covered by the Notice. The Notice nonetheless also provides that general step transaction doctrine principles apply.

Taxpayers will need to consider these rules when structuring acquisitions and divestitures.

b. Impact on Applicable Corporation Determination

The Notice provides three sets of rules regarding the determination of AFSI for a party to an applicable M&A transaction for purposes of determining Applicable Corporation status.

- Acquisition of Standalone Target or Entire Target Group. If a corporation acquires a standalone target or entire target group to form a new group, the acquirer group takes into account the AFSI of the acquired target (or target group) for the three-year taxable period ending with the taxable year in which the acquisition takes place (the “Three-Year Period”). The Applicable Corporation status (if it existed immediately prior to the transaction) of the target or target group terminates.

- Carve-Out. If a corporation acquires only a portion of a target group, the acquiring corporation takes into account only the portion of the AFSI of the target group allocated to the target (based on any reasonable method until proposed regulations are issued that specify a required allocation method) for the Three-Year Period, and the AFSI of the remaining target group is not adjusted. In other words, the AFSI allocated to the target is included in the AFSI for both the target’s group and the acquiror’s group for the Three-Year Period. If Applicable Corporation status existed for the target immediately prior to the transaction, it terminates.

- Spin-off or Split-off. If a corporation distributes a controlled corporation to its shareholders, the controlled corporation is allocated a portion of the AFSI of the distributing corporation (or the applicable group of which the distributing corporation is the parent) for the Three-Year Period (based on any reasonable allocation method until proposed regulations are issued that specify a required allocation method).[10] The AFSI of the distributing corporation (or the applicable group of which the distributing corporation is the parent) is not adjusted. Rather, as in the carve-out situation, the AFSI allocated to the controlled corporation is included in the AFSI for both the distributing and the controlled groups. If Applicable Corporation status existed for the controlled entity immediately prior to the transaction, it terminates.

Although the application of the CAMT rules to M&A and restructuring transactions is rife with complexity and ambiguity, the interim guidance provides taxpayers with much needed clarity regarding the application of the CAMT to these transactions and is a very helpful starting point for future regulations. It is not surprising that this is a key area in which the IRS and Treasury have requested comments.

3. Distressed Situations

The Notice provides relief for certain distressed corporations. Specifically, the Notice excludes from the calculation of AFSI—for purposes of both determining Applicable Corporation status and calculating CAMT liability—financial accounting gain that is excluded from income for U.S. federal income tax purposes under section 108(a)(1). The Notice also requires a reduction to the taxpayer’s CAMT tax attributes to the extent of the amount of the excluded cancellation of indebtedness income that results in a reduction of tax attributes under section 108(b) or Treas. Reg. § 1.1508-28.

The IRS and Treasury have requested comments regarding what CAMT attributes should be adjusted and what methodology should be used to adjust the CAMT attributes (and in what order).

4. Depreciable property and new refundable and transferable tax credit rules

The statute provides that tax depreciation deductions, rather than financial statement depreciation expense, are taken into account in computing AFSI for purposes of both determining Applicable Corporation status and calculating CAMT liability. The Notice includes various rules clarifying the application of this rule to certain tangible property. For example, the Notice provides that this rule applies only to depreciation deductions allowed under section 167 with respect to property that is in fact depreciated under section 168.[11] The Notice also makes clear that AFSI is reduced by tax depreciation that is capitalized to inventory under section 263A and recovered as part of cost of goods sold in computing gross income under section 61.

In addition, the Notice includes guidance regarding the new refundable and transferable tax credit rules for clean energy and advanced manufacturing projects. Specifically, the Notice provides that AFSI (again, for purposes of both determining Applicable Corporation status and calculating CAMT liability) is determined by taking into account appropriate adjustments to disregard amounts (i) that the taxpayer elects to treat as a payment of tax under section 48D(d) or 6417, (ii) treated as tax-exempt income under sections 48D(d) or 6417), and (iii) received from the transfer of an eligible credit that is not includible in the gross income of the transferring taxpayer under section 6418(b) or is treated as tax-exempt income under section 6418(c). Although the Notice does not provide color on the meaning of “appropriate adjustments,” the guidance is helpful in clarifying that the imposition of the CAMT is not intended to undermine the new energy incentives enacted last year.

__________________________

[1] As was the case with Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, the Senate’s reconciliation rules prevented changing the Act’s name. Therefore, the Inflation Reduction Act is actually “An Act to provide for reconciliation pursuant to title II of S. Con. Res. 14.” Pub. L. No. 117–169, tit. I, § 10201(d), 136 Stat. 1831 (Aug. 16, 2022).

The IRS issued a second notice on December 27, 2022, that provides important initial guidance on the new stock buyback excise tax. See our January 3, 2022, client alert “IRS and Treasury Issue Interim Guidance on New Stock Buyback Excise Tax,” available at https://www.gibsondunn.com/irs-and-treasury-issue-interim-guidance-on-new-stock-buyback-excise-tax/.

[2] The CAMT increases a taxpayer’s tax only to the extent that the 15 percent minimum tax (computed after taking into account applicable foreign tax credits) exceeds the taxpayer’s regular tax plus the base erosion and anti-abuse tax.

[3] A U.S. corporation is a member of a foreign-parented multinational group if it is included in the applicable financial statements of a group that has a foreign parent.

[4] Importantly, not all AFSI computational rules apply for both purposes.

[5] Unless indicated otherwise, all “section” references are to the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, as amended, and all “Treas. Reg. §” references are to the Treasury regulations promulgated thereunder.

[6] This guidance was necessary because the statute alone does not make clear whether the distributive share rule applies only in circumstances in which the corporate partner and the partnership are aggregated for purposes of calculating AFSI or in all cases.

[7] What is clear is that the typical private equity partnership is not required to take into account the book income of its portfolio companies. This position was proposed by Senate Democrats before the Act was passed in August of 2022, but Finance Committee member John Thune’s amendment removed that language from the bill.

[8] The list of specified transactions has notable exclusions. For example, it does not include tax-free capital contributions under section 118, like-kind exchanges under section 1031, involuntary conversions under section 1033, stock-for-stock exchanges under section 1036, or conversions of convertible debt under Revenue Ruling 72-265.

[9] The Notice requires the transaction not “result” in any amount of gain or loss for U.S. federal income tax purposes. The proposed regulations should clarify that “result” in this context means recognition (and not realization) of gain or loss.