Please join our team of Global Financial Regulatory experts as we discuss the latest legal and regulatory developments around the use of artificial intelligence (AI) by financial institutions across the world’s major financial centers. During this webcast, our market-leading team provides their insights into:

- Regulatory issues and concerns in relation to the current and potential use cases of AI by financial institutions; and

- The attitudes of financial regulators across the US, United Kingdom, Europe, Hong Kong, Singapore and the Middle East to the rapidly evolving use of AI by the institutions they regulate.

In addition, the team provides their predictions for the future of regulatory policy, supervision and enforcement in relation to the use of AI by financial institutions based on their extensive experience in these areas with the key global regulators.

PANELISTS:

William R. Hallatt (moderator) is a partner in the Hong Kong office. He is co-chair of the firm’s Global Financial Regulatory group and head of the Asia-Pacific Financial Regulatory practice. His full-service financial services regulatory practice provides comprehensive contentious and advisory support as a trusted advisor to the world’s leading financial institutions.

Michelle Kirschner is a partner in the London office, and co-chair of the firm’s Global Financial Regulatory group. She advises a broad range of financial institutions, including investment managers, integrated investment banks, corporate finance boutiques, private fund managers and private wealth managers at the most senior level. Michelle has a particular expertise in fintech businesses, having advised a number of fintech firms on regulatory perimeter issues.

Sara K. Weed is a partner in the Washington, D.C. office, and co-chair of the Global Fintech and Digital Assets Practice Group. Sara’s fintech’s practice spans both regulatory and transactional advice for a range of clients, including traditional financial institutions, non-bank financial services companies and technology companies.

Emily Rumble is an of counsel in the Hong Kong office, and is a member of the firm’s Global Financial Regulatory Practice Group. She advises firms on a wide range of contentious and non-contentious financial regulatory matters. Her contentious practice is focused on advising clients on their most significant regulatory investigations by the Hong Kong Securities and Futures Commission and Hong Kong Monetary Authority. Emily frequently advises a wide range of investment banking clients on complex non-contentious regulatory matters, with a particular focus on culture, conduct and governance matters.

Grace Chong is an of counsel in the Singapore office, and heads the Financial Regulatory practice in Singapore. She has extensive experience advising on cross-border and complex regulatory matters, including licensing and conduct of business requirements, regulatory investigations, and regulatory change. A former in-house counsel at the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS), she regularly interacts with key regulators, is closely involved in regional regulatory reform initiatives and has led discussions with regulators on behalf of the financial services industry.

Sameera Kimatrai is an English law qualified of counsel in the Dubai office, and a member of the firm’s Financial Regulatory Practice Group. She has experience advising governments, regulators and a broad range of financial institutions in the UAE including investment managers, commercial and investment banks, payment service providers and digital asset service providers on complex regulatory issues both in onshore UAE and in the financial free zones.

MCLE CREDIT INFORMATION:

This program has been approved for credit in accordance with the requirements of the New York State Continuing Legal Education Board for a maximum of 1.0 credit hour, of which 1.0 credit hour may be applied toward the areas of Cybersecurity, Privacy and Data Protection-General. This course is approved for transitional/non-transitional credit.

Attorneys seeking New York credit must obtain an Affirmation Form prior to watching the archived version of this webcast. Please contact CLE@gibsondunn.com to request the MCLE form.

Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP certifies that this activity has been approved for MCLE credit by the State Bar of California in the amount of 1.0 hour toward the areas of Technology in the Practice of Law.

California attorneys may claim “self-study” credit for viewing the archived version of this webcast. No certificate of attendance is required for California “self-study” credit.

© 2024 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP. All rights reserved. For contact and other information, please visit us at www.gibsondunn.com.

Attorney Advertising: These materials were prepared for general informational purposes only based on information available at the time of publication and are not intended as, do not constitute, and should not be relied upon as, legal advice or a legal opinion on any specific facts or circumstances. Gibson Dunn (and its affiliates, attorneys, and employees) shall not have any liability in connection with any use of these materials. The sharing of these materials does not establish an attorney-client relationship with the recipient and should not be relied upon as an alternative for advice from qualified counsel. Please note that facts and circumstances may vary, and prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome.

Gibson Dunn’s Workplace DEI Task Force aims to help our clients develop creative, practical, and lawful approaches to accomplish their DEI objectives following the Supreme Court’s decision in SFFA v. Harvard. Prior issues of our DEI Task Force Update can be found in our DEI Resource Center. Should you have questions about developments in this space or about your own DEI programs, please do not hesitate to reach out to any member of our DEI Task Force or the authors of this Update (listed below).

Key Developments:

On March 12, 2024, the Fourth Circuit affirmed in part and vacated in part the district court’s decision in Duvall v. Novant Health, Inc., — F.4th —, 2024 WL 1057768 (4th Cir. Mar. 12, 2024). The plaintiff, a white male marketing executive, sued Novant, alleging that he was fired without cause from his management position because of his race and sex. At trial, the plaintiff relied on evidence that Novant maintained a “goal of remaking the workforce to look like the community it served,” and argued that his firing fit a pattern of similar actions by Novant. A jury found in the plaintiff’s favor and awarded him $10 million in punitive damages, in addition to back pay and other damages. Novant filed a post-trial motion for judgment as a matter of law and a motion to set aside the jury’s damages award. The district court denied the motion for judgment as a matter of law but granted in part Novant’s motion to set aside punitive damages, reducing the award to the Title VII statutory maximum of $300,000. Novant appealed to the Fourth Circuit, which affirmed the district court’s refusal to enter judgment as a matter of law because “[t]here was more than sufficient evidence for a reasonable jury to determine that Duvall’s race, sex, or both motivated Novant Health’s decision to fire him.” This evidence included that the plaintiff was “fired in the middle of a widescale D&I initiative” that sought to “embed diversity and inclusion throughout” the company, including by “employing D&I metrics,” committing to “adding additional dimensions of diversity to the executive and senior leadership teams,” and incorporating “a system wide decision making process that includes a diversity and inclusion lens.” But the appellate court held that the plaintiff failed to present sufficient evidence that Novant exhibited “malice or . . . reckless indifference” because the plaintiff did not present affirmative evidence that the decisionmaker in the plaintiff’s termination had any personal knowledge of federal antidiscrimination law. Because the plaintiff failed to show that the decisionmaker acted with malice or reckless indifference, the court set aside the award of punitive damages.

On March 11, 2024, the Tenth Circuit affirmed the dismissal of a white male former employee’s hostile work environment claims against the Colorado Department of Corrections, in Young v. Colorado Dep’t of Corrections, — F.4th —, 2024 WL 1040625 (10th Cir. Mar. 11, 2024). The former employee claimed that the Department of Corrections’ training materials for its “Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion” programs subjected him to a hostile work environment by, among other things, “stating that all whites are racist [and] that white individuals created the concept of race in order to justify the oppression of people of color.” The District Court dismissed the case for failure to state a claim and the Tenth Circuit affirmed, holding that the plaintiff had failed to allege that the DEI training, which only occurred once during the plaintiff’s employment, constituted severe and pervasive harassment. However, the court did note that “Mr. Young’s objections to the contents of the EDI training are not unreasonable: the racial subject matter and ideological messaging in the training is troubling on many levels. As other courts have recognized, race-based training programs can create hostile workplaces when official policy is combined with ongoing stereotyping and explicit or implicit expectations of discriminatory treatment. The rhetoric of these programs sets the stage for actionable misconduct by organizations that employ them.”

On March 6, 2024, the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit affirmed the district court’s dismissal of medical advocacy association Do No Harm’s reverse discrimination claims against Pfizer based on lack of standing in Do No Harm v. Pfizer, Inc., — F.4th —, 2024 WL 949506 (2d Cir. Mar. 6, 2024). Suing on behalf of two anonymous members, Do No Harm alleged that Pfizer violated Section 1981, Title VII, and New York law by excluding white and Asian applicants from its Breakthrough Fellowship Program, which provides minority college seniors with summer internships, two years of employment post-graduation, mentoring, and a scholarship. In its opinion affirming the district court’s dismissal, the Second Circuit held that, under the “clear language” of Supreme Court precedent, an organization must name at least one affected member to establish Article III standing. The court explained that such a naming requirement ensures that the members are “genuinely” injured and “not merely enabling the organization to lodge a hypothetical legal challenge.” For a more fulsome discussion of this decision, see our March 11 Client Alert.

A district court in the Northern District of Texas issued an opinion on March 5, 2024, in Nuziard v. Minority Business Development Agency, No. 4:23-cv-00278-P, 2023 WL 3869323 (N.D. Tex.), holding that the racial presumption used in apportioning federal funds for minority business assistance violates the Fifth Amendment’s equal protection guarantee. Applying SFFA v. Harvard, the court held that the Minority Business Development Agency’s presumption of social or economic disadvantage does not satisfy strict scrutiny because, even though the Agency might have a compelling interest in addressing discrimination in government contracting, the Agency’s program for eliminating such discrimination was not narrowly tailored to achieve that interest. A more detailed discussion of this opinion can be found in our March 11 Client Alert.

On March 4, 2024, the Eleventh Circuit affirmed the district court’s order preliminarily enjoining operation of Florida’s “Stop WOKE Act” in Honeyfund.com, Inc. v. DeSantis, — F.4th —, 2024 WL 909379 (11th Cir. Mar. 4, 2024). Among other things, the “Stop WOKE Act” prohibits employers from requiring employees to participate in trainings that identify certain groups of people as “privileged” or “oppressors.” Florida argued that the Act did not fall within the purview of the First Amendment because it regulated conduct rather than speech. The Eleventh Circuit rejected this argument, holding that the law constituted both content and viewpoint discrimination that did not survive strict scrutiny. Writing for the court, Judge Britt C. Grant stated that “restricting speech is the point of the [Stop WOKE Act],” and opined that the merits of controversial views are “decided in the clanging marketplace of ideas rather than a codebook or a courtroom.”

Representatives James Comer (R-Ky.) and Pat Fallon (R-Tex.) sent a letter on March 1, 2024, to the EEOC “to better understand EEOC’s current posture ensuring the enforcement of longstanding prohibitions on racially discriminatory policies in employment practices.” Acting in their capacities as the Chair of the Committee on Oversight and Accountability and Chair of the Subcommittee on Economic Growth, Energy Policy, and Regulatory Affairs, respectively, Reps. Comer and Fallon referenced statements by government officials in the wake of SFFA v. Harvard, including comments by EEOC Commissioner Andrea Lucas and a letter by a group of Republican state attorneys general—both of which warned corporate leaders about the decision’s implications for corporate diversity programs. Emphasizing that the EEOC must take all possible steps to “prevent and end unlawful employment practices that discriminate on the basis of an individual’s race or color,” Reps. Comer and Fallon demanded that, by no later than March 15, 2024, the EEOC produce various documents and information, including Title VII enforcement guidance disseminated to employers, internal training materials, any documents containing “numerical accounting of enforcement actions” related to Title VII race discrimination, and any documents or communications related to SFFA v. Harvard. Reps. Comer and Fallon also instructed the EEOC to provide a staff-level briefing on the matter no later than March 8, 2024.

On February 29, 2024, Brian Beneker, a heterosexual, white male writer, sued CBS, alleging that its de facto hiring policy discriminated against him on the bases of sex, race, and sexual orientation in Beneker v. CBS Studios, Inc., No. 2:24-cv-01659 (C.D. Cal. 2024). In his complaint, Beneker alleges that CBS violated Section 1981 and Title VII by refusing to hire him as a staff writer on the TV show “Seal Team,” instead hiring several black writers, female writers, and a lesbian writer. Beneker is requesting a declaratory judgment that CBS’s de facto hiring policy violates Section 1981 and/or Title VII, injunctions barring CBS from continuing to violate Section 1981 and Title VII and requiring CBS to offer Beneker a full-time job as a producer, and damages. Beneker is represented by America First Legal (AFL).

Indiana Senate Bill 202 (S.B. 202) passed both chambers of the Indiana General Assembly with amendments and was sent to Governor Eric Holcomb’s desk on February 29, 2024. If enacted, S.B. 202 will direct the boards of trustees of state higher education institutions to refocus diversity committees and tenure decisions on “intellectual diversity”; prohibit traditional diversity statements in admissions, hiring, and contracting; dictate a policy of neutrality with respect to institutional viewpoints; and require annual reporting on DEI-related operations and spending. The American Association of University Professors has called for a veto of the bill, and DePauw University filed a formal opposition. Governor Holcomb has until March 15, 2024 to sign or veto the bill.

On February 28, 2024, the Wisconsin Institute for Law & Liberty (WILL) called upon the Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin to investigate and reform various race-based programs implemented by the University and to make a public statement clarifying that the University does not condone such “discriminatory” programs. WILL commended the University’s initial compliance with the SFFA decision as it related to admissions and hiring, but identified ten examples of programs––including awards, scholarships, fellowships, internships, group therapy services, a mentorship program, and a housing program––that WILL alleges continue to consider race as either the sole criterion for eligibility or as one of multiple factors. WILL argues that these programs violate SFFA and has called for them to be opened to all students.

The Equal Protection Project (EPP) of the Legal Insurrection Foundation sent a letter on February 26, 2024, to the Office of Civil Rights (OCR) at the U.S. Department of Education, alleging that Western Illinois University (WIU) offers sixteen discriminatory scholarships. The letter complains that the scholarships restrict eligibility or give preference to black and Latino students and students that identify as LGBTQI+. EPP argues that these scholarships discriminate on the basis of race in violation of Title VI and on the basis of sex and sexual orientation in violation of Title IX. Because WIU is a public university, EPP also alleges that the scholarships violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. EPP has asked OCR to open a formal investigation into the University and impose any remedial relief that the law permits in holding the University accountable for its alleged misconduct.

Media Coverage and Commentary:

Below is a selection of recent media coverage and commentary on these issues:

- New York Times, “Can You Create A Diverse College Class Without Affirmative Action?” (Mar. 9): Writing for the New York Times, Aatish Bhatia and Emily Badger report on an analysis the Times performed in conjunction with Sean Reardon, a professor at Stanford, and Demetra Kalogrides, a Stanford senior researcher, using statistical data to model four potential alternatives to “race-conscious” college admissions: (1) giving preference to low-income students; (2) giving preference to low-income students who attend higher poverty schools; (3) giving preference to students who outperform their peers with similar disadvantages; and (4) expanding the applicant pool. Each scenario focuses on increasing economic diversity as a means to bolster the number of minorities enrolled in the most elite colleges. According to the analysis, the fourth scenario that focuses on targeted recruiting by elite universities in areas with a critical mass of historically disadvantaged students best mirrors the minority admissions rate at elite colleges pre-SFFA. The authors note the logistical and financial challenges universities face in broadening their recruiting approaches. But as Jill Orcutt, the global lead for consulting with the American Association of Collegiate Registrars and Admissions Officers, observes, “this kind of outreach” is “everything.”

- Bloomberg Law, “Business Is Booming for DEI Lawyers as Firms Ask ‘What’s Legal?’” (March 5): Simone Foxman of Bloomberg News reports on the increase in corporations seeking the help of law firms to navigate the tumultuous landscape of diversity, equity, and inclusion programs following SFFA. NYU Law Professor Kenji Yoshino explained that he sees “no end in sight” for companies seeking help from attorneys to navigate the emerging DEI landscape. Gibson Dunn Partner and Labor & Employment Group Co-Chair Jason Schwartz observed that “[l]ots of clients are wanting to do audits, review all DEI efforts, board diversity, socially conscious investing to assess risk and figure out what—if any—changes they want to make . . . There is a never ending tide.” Now, more than ever, corporations are deciding to revisit their previous DEI efforts with the help of subject-matter experts to minimize risks and liability while retaining the benefits of these programs.

- JDJournal, “The Changing Landscape of Corporate Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Programs” (March 5): JDJournal’s Maria Lenin Laus reports on the corporate world’s increased demand for DEI specialists following the “intensifying backlash against DEI initiatives, fueled by conservative groups and influential figures like Bill Ackman and Elon Musk.” She observes that “the discourse surrounding [DEI] programs has escalated to unprecedented levels, resulting in a surge in demand for specialists in this field.” She identifies Gibson Dunn’s Jason Schwartz as a specialist who has experienced a significant uptick in inquiries from the corporate world as companies seek to engage those with expertise in this rapidly evolving space.

- BNN Bloomberg, “Wall Street’s DEI Retreat Has Officially Begun” (March 3): Writing for BNN Bloomberg, Max Abelson, Simone Foxman, and Ava Benny-Morrison examine how major companies have made public shifts away from their diversity and inclusion initiatives in the wake of “[t]he growing conservative assault on DEI.” As an example, the authors note Bank of America’s efforts to broaden eligibility for certain internal programs that previously had focused on women and minorities. The article pinpoints the Supreme Court’s decision in SFFA as the inflection point for increased scrutiny of diversity initiatives on Wall Street. In the authors’ view, DEI swiftly declined in importance to many corporations following the decision. But spokespeople for BNY Mellon, JPMorgan, and Goldman Sachs each reasserted their commitment to promoting an inclusive workplace with people from diverse backgrounds. And the article notes that no corporations have yet “signaled a full-blown retreat” from DEI.

- NBC News, “University of Florida eliminates all diversity, equity and inclusion positions due to new state rule” (March 2): NBC News’s Rebecca Cohen reports on an administrative memo issued by the University of Florida that declared that the University has “eliminated all diversity, equity, and inclusion positions” to comply with Florida Board of Governor’s regulation 9.016. The University reallocated $5 million in funds previously dedicated to DEI initiatives and terminated the employment of dozens of university employees working in DEI-focused offices. Florida Governor Ron DeSantis took to “X” to celebrate the move, stating “DEI is toxic and has no place in our public universities. I’m glad that Florida was the first state to eliminate DEI and I hope more states follow suit.” But the decision has received much criticism from other politicians, with Congressional Black Caucus Chairman Steven Horsford saying University of Florida’s decision “is far out of step with the standards and values expected of a public institution of higher education.”

Case Updates:

Below is a list of updates in new and pending cases:

1. Contracting claims under Section 1981, the U.S. Constitution, and other statutes:

- Do No Harm v. Lee, No. 3:23-cv-01175-WLC (M.D. Tenn. 2023): On November 8, 2023, Do No Harm, a conservative advocacy group representing doctors and healthcare professionals, sued Tennessee Governor Bill Lee, challenging state policies for appointing positions on the Tennessee Board of Podiatric Medical Examiners. Under Tennessee law dating back to 1988, the governor must “strive to ensure” that at least one board member of the six-member board is a racial minority. Do No Harm brought the challenge under the Equal Protection Clause and requested a permanent injunction against the law.

- Latest update: On February 2, 2024, Governor Lee moved to dismiss the complaint for lack of standing, arguing that (1) Do No Harm had not established that any of its members had been injured by the policy, since all seats reserved for practitioners on the board had been filled, precluding any chance for a Do No Harm member to be considered and rejected, and (2) the board currently has a member who belongs to a racial minority so there are no race-related barriers to board membership until the member’s term ends in 2027. On February 16, Do No Harm filed a response, arguing that (1) it satisfied standing requirements via anonymous declarations from Member A and Member B, and (2) the defendant did not provide sufficient evidence that a current board member is African American. On March 1, 2024, the defendant filed a reply, arguing that Do No Harm lacked standing because “pseudonymity is not a free pass to standing in the [Sixth] Circuit,” and contesting the plaintiff’s factual allegations regarding the board member’s race.

- Nistler v. Walz, No. 24-cv-186-ECT-LIB (D. Minn. 2024): On January 24, 2024, Lance Nistler, a white, male farmer in Minnesota, sued Governor Walz and the Commissioner of the Minnesota Department of Agriculture, alleging that the state’s Down Payment Assistance Program (DPAP) violates the Equal Protection Clause. The DPAP grants farmers up to $15,000 to help purchase their first farms and prioritizes “emerging farmers,” including women, persons with disabilities, members of a community of color, and members of the LGBTQIA+ community. Plaintiff alleges that he applied, and was otherwise qualified, for the DPAP but was denied acceptance solely because of his race and gender. On February 13, Governor Walz was dismissed as a party.

- Latest update: On February 15, the Commissioner filed an answer, denying that the plaintiff would have received the grant if he had been a different race or gender, and denying that any stated preference for “emerging farmers” is not a “compelling state interest.”

- Students for Fair Admissions v. U.S. Military Academy at West Point, No. 7:23-cv-08262 (S.D.N.Y. 2023): On September 19, 2023, SFFA sued West Point, relying on the Supreme Court’s decision in SFFA v. Harvard in arguing that the military academy’s affirmative action program violated the Fifth Amendment by taking applicants’ race into account when making admission decisions. SFFA also filed a motion for preliminary injunction to halt West Point’s affirmative action program during the course of the litigation. The district court denied SFFA’s request and the Second Circuit affirmed the district court’s order. On February 2, 2024, the Supreme Court denied SFFA’s request for an emergency order overturning the district court’s decision.

- Latest update: On February 19, 2024, SFFA filed an amended complaint, re-alleging that West Point’s consideration of race in the admissions process violates the Equal Protection Clause because race is “determinative for hundreds of applicants each year.” SFFA further argues that West Point’s justifications for its affirmative action program, including unit cohesion, battlefield lethality, recruitment, retention, and preservation of public legitimacy, are not furthered by admission based on race. West Point’s response to the complaint is due on April 22, 2024.

- Do No Harm v. Edwards, No. 5:24-cv-16-JE-MLH (W.D. La. 2024): On January 4, 2024, Do No Harm sued Governor Edwards of Louisiana over a 2018 law requiring a certain number of “minority appointee[s]” to be appointed to the State Board of Medical Examiners. Do No Harm brought the challenge under the Equal Protection Clause and requested a permanent injunction against the law.

- Latest update: On February 28, 2024, Governor Edwards answered the complaint, denying all allegations including allegations related to Do No Harm’s standing.

- Do No Harm v. National Association of Emergency Medical Technicians, No. 3:24-cv-11-CWR-LGI (S.D. Miss. 2024): On January 10, 2024, Do No Harm challenged the diversity scholarship program operated by the National Association of Emergency Medical Technicians (NAEMT). NAEMT awards up to four $1,250 scholarships to “students of color . . . who intend to become an EMT or Paramedic.” Do No Harm requested a temporary restraining order, preliminary injunction, and permanent injunction against the program. On January 23, 2024, the court denied Do No Harm’s motion for a TRO and expressed skepticism that Do No Harm had standing to bring its Section 1981 claim, because the Do No Harm member had “only been deterred from applying, rather than refused a contract.”

- Latest update: On February 29, 2024, NAEMT filed its answer and a motion to dismiss the complaint, arguing that Do No Harm and anonymous Member A lacked standing to bring the case and, in the alternative, that Do No Harm had failed to state a viable Section 1981 claim because NAEMT did not prevent Member A from applying due to her race. Also on February 29, 2024, Do No Harm withdrew its motion for a preliminary injunction, explaining that NAEMT had agreed not to close the application window or select scholarship recipients until the litigation is resolved.

2. Employment discrimination and related claims:

- Bresser v. The Chicago Bears Football Club, Inc., No. 1:24-cv-02034 (N.D. Ill. 2024): On March 11, 2024, a white male law student filed a complaint against the Chicago Bears, alleging that the team refused to hire him as a “diversity legal fellow” based on his race and sex. The plaintiff alleges that, despite meeting the substantive job qualifications, the Bears rejected his application after a Bears employee viewed his LinkedIn profile, which contains his photo. The complaint asserts claims for race and sex discrimination under Title VII, Section 1981, and Illinois law, as well as conspiracy claims under Sections 1985 and 1986.

- Latest update: According to the docket, it does not appear that the complaint has yet been served.

- Langan v. Starbucks Corporation, No. 3:23-cv-05056 (D.N.J. 2023): On August 18, 2023, a white female former employee filed a complaint against Starbucks, claiming she was wrongfully accused of racism and terminated after she rejected Starbucks’ attempt to deliver “Black Lives Matter” T-shirts to her store. The plaintiff alleged that she was discriminated and retaliated against on the basis of her race and disability as part of a policy of favoritism toward non-white employees. On December 8, 2023, Starbucks filed its motion to dismiss arguing that certain claims are beyond the statute of limitations, and that the plaintiff failed to plead a Section 1981 claim because she did not plead facts distinct from those supporting her Title VII claims and did not show that race was the but-for cause of the loss of a contractual interest.

- Latest update: On January 28, 2024, the plaintiff opposed Starbucks’ motion to dismiss, arguing that her claims were not time-barred and advocating for a different standard to be applied to her Section 1981 claim. On February 23, 2024, Starbucks filed its reply, reiterating that certain claims were time-barred and others should be dismissed because they failed to state a claim.

- King v. Johnson & Johnson, No. 2:24-cv-968-MAK (E.D. Pa. 2024): On March 6, 2024, a fifty-nine year-old white male former employee sued Johnson & Johnson alleging violations of Title VII, Section 1981, and the ADEA. The plaintiff alleged that Johnson & Johnson reassigned him to a position that provided no career advancement opportunities, refused to hire him for any of the 30 internal positions for which he applied and was qualified, and ultimately terminated his employment as part of a corporate restructuring. The plaintiff alleged that each of these adverse employment actions can be traced to Johnson & Johnson’s DEI initiative, which has “vilified/stereotyped Caucasian males as problematic and inherently unaligned with the DEI program.”

- Latest update: According to the docket, it does not appear that the complaint has yet been served.

3. Actions against educational institutions:

- Chu, et al. v. Rosa, No. 1:24-cv-75 (N.D.N.Y. 2024): On January 17, 2024, a coalition of education groups sued the Education Commissioner of New York, alleging that its free summer program discriminates on the bases of race and ethnicity. The Science and Technology Entry Program (STEP) permits students who are Black, Hispanic, Native American, and Alaskan Native to apply regardless of their family income level, but all other students, including Asian and white students, must demonstrate “economically disadvantaged status.” The plaintiffs sued under the Equal Protection Clause and requested preliminary and permanent injunctions against the enforcement of the eligibility criteria.

- Latest update: The defendant’s response to the complaint is due March 18, 2024.

DEI Legislation

Our DEI Task Force is tracking state and federal legislative developments relating to DEI. These developments span a variety of DEI-related bills, including those involving diversity statements, DEI officers and training, DEI contracting and funding, and regulation of higher education.

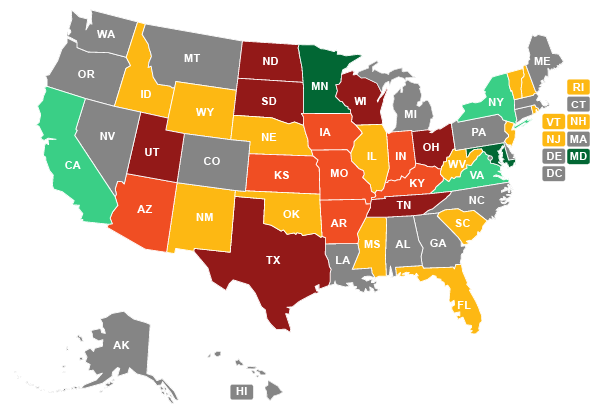

|

Current as of March 13.

Gibson Dunn’s lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding these developments. Please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, any member of the firm’s Labor and Employment practice group, or the following practice leaders and authors:

Jason C. Schwartz – Partner & Co-Chair, Labor & Employment Group

Washington, D.C. (+1 202-955-8242, jschwartz@gibsondunn.com)

Katherine V.A. Smith – Partner & Co-Chair, Labor & Employment Group

Los Angeles (+1 213-229-7107, ksmith@gibsondunn.com)

Mylan L. Denerstein – Partner & Co-Chair, Public Policy Group

New York (+1 212-351-3850, mdenerstein@gibsondunn.com)

Zakiyyah T. Salim-Williams – Partner & Chief Diversity Officer

Washington, D.C. (+1 202-955-8503, zswilliams@gibsondunn.com)

Molly T. Senger – Partner, Labor & Employment Group

Washington, D.C. (+1 202-955-8571, msenger@gibsondunn.com)

Blaine H. Evanson – Partner, Appellate & Constitutional Law Group

Orange County (+1 949-451-3805, bevanson@gibsondunn.com)

© 2024 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP. All rights reserved. For contact and other information, please visit us at www.gibsondunn.com.

Attorney Advertising: These materials were prepared for general informational purposes only based on information available at the time of publication and are not intended as, do not constitute, and should not be relied upon as, legal advice or a legal opinion on any specific facts or circumstances. Gibson Dunn (and its affiliates, attorneys, and employees) shall not have any liability in connection with any use of these materials. The sharing of these materials does not establish an attorney-client relationship with the recipient and should not be relied upon as an alternative for advice from qualified counsel. Please note that facts and circumstances may vary, and prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome.

An overview of intellectual property considerations in M&A transactions, which can impact valuation and the ability to operate after closing.

In today’s M&A transactions, intellectual property (“IP”) represents an increasingly critical component of a target company’s value. Therefore, during the due diligence process it is important to understand what IP a potential target actually owns, what third-party IP it relies on, whether the target may be infringing a third party’s IP, as well as how the proposed transaction could impact the buyer’s rights in the target’s IP.

Below, we highlight several IP considerations and red flags in U.S.-based M&A transactions. For transactions involving non-U.S. target companies or businesses, local law considerations may need to be assessed.

- Scope of IP; Impact of Transaction Structure

Understanding the scope of IP that will be included in a particular transaction, and confirming whether the target company or seller actually owns the IP that it purports to own or sell, should be a primary concern for a potential buyer. A buyer should conduct global database searches to confirm the registered IP held by a target company or seller, as well as to identify any chain of title issues, recorded liens, and any legal or regulatory proceedings that may have been initiated with respect to such IP.

In an equity purchase transaction, the buyer will typically acquire all of the target’s (or its parent’s) equity interests, and therefore inherit all of the target’s IP holdings automatically by virtue of the transaction. Conversely, in a transaction structured as a purchase of assets, a buyer will only acquire the IP that is expressly transferred under the purchase agreement. As such, it is critical to understand what IP is included and what IP (if any) will remain with the seller, and confirm that the transferred IP is sufficient to operate the target’s business.

It is also important to review any outbound licenses to determine whether the target has granted to a third party any exclusivity or ownership rights in the target’s IP, and understand whether any of the target company’s contracts contain a “springing license” that could grant to a third party IP rights by virtue of the consummation of the proposed transaction, as this could impact the valuation of the target company.

In addition to understanding what IP a target owns, it is important for a buyer to understand what third-party licenses are required to operate the target’s business. A buyer should review those licenses to identify any restrictions on the buyer’s ability to receive the benefit of those licenses post-closing. While license agreements will often flow through automatically in a transaction structured as an equity purchase, in an asset purchase scenario each license agreement must be expressly assigned by the seller to the buyer, which in many cases may require the consent of a third party. Moreover, even in an equity purchase scenario, it is important to diligence and understand any change in control restrictions, including anti-assignment provisions, that may be triggered by the proposed structure. Unlike typical contracts, IP licenses are considered to be personal to the licensee and by default are not transferable without the consent of the licensor. Proper review of a business’s material license agreements is critical to avoid last minute surprises or situations in which a third party can create unanticipated hurdles to a smooth deal closing. If consent cannot be obtained, it is important to understand the effect losing the IP rights (or license fees or royalties) will have on the target’s business, as this may impact the deal’s valuation.

- Comingling of Intellectual Property

In some instances, a seller may have comingled certain IP among the business it proposes to sell and the businesses it plans to retain. In such instances, both the buyer and the seller may need continued access to that IP following the closing of the transaction. Comingling of IP in this manner may require the buyer and seller to negotiate an ongoing license agreement between them, which will typically establish clearly defined purposes for which each party may (and may not) use the IP going forward. In some cases, the parties may negotiate time-limited restrictive covenants in addition to such ongoing license agreements. Restrictive covenants should always be reviewed by an antitrust expert to confirm they are drafted in an enforceable manner.

- Treatment of IP in Employee and Consultant Agreements

It is important to evaluate the target’s forms of employee and independent contractor invention assignment agreements to confirm that such individuals have properly assigned to the target all applicable IP rights – or, if not, to identify critical gaps that must be remediated before the transaction can close. Best practice is that such agreements should contain presently effective assignment language that makes the IP assignment from the employee or contractor to the target company effective immediately, rather than requiring any future execution of documents. Companies hoping to be acquired in the near future may wish to review these forms and improve them before any deficiencies turn into a deal hurdle. Founders in particular should ensure that their companies are the proper owners of any founder-created IP, as buyers and even potential investors will be on the lookout for any possibility that a founder could replicate the business under a new company.

If any IP development work is performed outside of the United States, it is advisable to consult with local counsel in the relevant jurisdiction to ensure that the invention assignment provisions are enforceable under local law.

- AI Generated Content

As companies are increasingly relying on artificial intelligence (“AI”), a buyer should review whether and how the target company uses AI in its business. Recently, the U.S. Copyright Office clarified its practices for examining and registering works containing material generated by AI. However, the use and ownership of AI is an area of the law that is currently under development as the legal system attempts to catch up with this new technology. If a target relies on AI tools to generate content considered material to the business value, careful analysis should be undertaken to determine whether the AI outputs are actually copyrightable, or whether they will be deemed outside the scope of copyright protection. Further, it is important to understand the inputs a target company uses to train its AI, as certain uses of third-party copyrighted materials can lead to claims of infringement or misappropriation.

- Joint Ownership

Joint ownership of IP creates complications that many buyers and sellers may wish to avoid. For example, each joint owner of a patented invention can independently sell, license or otherwise exploit the patent without any duty to account to or seek consent from any other joint owner (including the right to license the patent to a third party that is in an infringement dispute with the other party over such patent). A buyer should therefore pay special attention to agreements that cover joint ventures or joint development of IP or technology, and growth-stage companies looking to make themselves attractive to future buyers should carefully weigh the benefits and potential risks of joint ownership before entering into any such arrangements.

- Upward-Reaching Affiliate Issue

A buyer (especially if it has a valuable patent monetization program) should conduct a careful review of a target company’s license agreements – particularly any with the buyer’s direct competitors – to identify provisions that may become binding on the buyer of the target company upon closing. In many agreements, the term “affiliate” is defined broadly to include any entity that controls, is controlled by or is under common control with the licensor, such that, upon closing, the license granted by the target could be deemed to encompass the buyer’s entire IP portfolio as well.

- Adequate Protection of Trade Secrets (Including Source Code)

For many companies, trade secrets are their most valuable IP asset. Therefore, it is important for a buyer to confirm that such trade secrets are adequately protected, including the source code to the target’s proprietary software. A buyer should confirm that all employees and contractors, as well as other third parties with access to the target company’s trade secrets, have executed non-disclosure agreements, and should review such agreements to ensure that they reasonably protect the target company’s trade secrets and other confidential information and prohibit recipients thereof from disclosing such information. It is also important for a buyer to confirm that the target company has industry-standard controls in place, including appropriate organizational, administrative, technical and physical measures, to ensure the confidentiality and security of the IT systems that house its trade secrets and other confidential information. If proprietary software is the target’s most valuable IP asset, the buyer should also confirm that the source code to the software has not been disclosed to (and is not required to be disclosed to) any third parties and review any source code escrow agreements to confirm that the proposed transaction would not trigger a release.

- IP-related Disputes

Finally, a buyer should review any IP-related lawsuits, settlements, and coexistence arrangements, as well as any claims of IP infringement, including in the form of offers or invitations to obtain a license or requests for indemnification, and ascertain the status and materiality of, as well as the likely cost associated with resolving, any pending disputes.

Settlement agreements may include a covenant not to sue, whereby the target company agrees not to assert its IP rights against the counterparty for particular uses or products. A buyer should consider how this would impact its rights in the acquired IP, as well as whether an overly broad definition of “affiliate” could cause the buyer to be similarly bound not to enforce its IP against the other party, either of which could affect the target company’s valuation depending on the buyer’s go-forward plans.

Gibson Dunn lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have about these developments. Please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, any member of the firm’s Mergers & Acquisitions, Private Equity, or Technology Transactions practice groups, or the following authors and practice leaders:

Technology Transactions:

Daniel Angel – New York (+1 212.351.2329, dangel@gibsondunn.com)

Carrie M. LeRoy – Palo Alto (+1 650.849.5337, cleroy@gibsondunn.com)

Meghan Hungate – New York (+1 212.351.3842, mhungate@gibsondunn.com)

Mergers and Acquisitions:

Robert B. Little – Dallas (+1 214.698.3260, rlittle@gibsondunn.com)

Saee Muzumdar – New York (+1 212.351.3966, smuzumdar@gibsondunn.com)

Private Equity:

Richard J. Birns – New York (+1 212.351.4032, rbirns@gibsondunn.com)

Wim De Vlieger – London (+44 20 7071 4279, wdevlieger@gibsondunn.com)

Federico Fruhbeck – London (+44 20 7071 4230, ffruhbeck@gibsondunn.com)

Scott Jalowayski – Hong Kong (+852 2214 3727, sjalowayski@gibsondunn.com)

Ari Lanin – Los Angeles (+1 310.552.8581, alanin@gibsondunn.com)

Michael Piazza – Houston (+1 346.718.6670, mpiazza@gibsondunn.com)

John M. Pollack – New York (+1 212.351.3903, jpollack@gibsondunn.com)

© 2024 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP. All rights reserved. For contact and other information, please visit us at www.gibsondunn.com.

Attorney Advertising: These materials were prepared for general informational purposes only based on information available at the time of publication and are not intended as, do not constitute, and should not be relied upon as, legal advice or a legal opinion on any specific facts or circumstances. Gibson Dunn (and its affiliates, attorneys, and employees) shall not have any liability in connection with any use of these materials. The sharing of these materials does not establish an attorney-client relationship with the recipient and should not be relied upon as an alternative for advice from qualified counsel. Please note that facts and circumstances may vary, and prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome.

The 2024 presidential and congressional elections could bring seismic shifts in the way government interacts with individuals, businesses, and other entities. While the results of those elections cannot be predicted with certainty, it is not too soon to start preparing for possible scenarios. This webcast examines how public policy issues, congressional investigations, and administrative actions are likely to be shaped by the 2024 elections.

PANELISTS:

Michael Bopp is a partner in the Washington, D.C. office of Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher. He chairs the Congressional Investigations Practice Group practice and he is a member of the White Collar Defense and Investigations Crisis Management Practice Groups. He also co-chairs the firm’s Public Policy Practice Group and is a member of its Financial Institutions Practice Group. Mr. Bopp’s practice focuses on congressional investigations, internal corporate investigations, and other government investigations. Michael spent more than a dozen years on Capitol Hill including as Staff Director and Chief Counsel to the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee under Senator Susan Collins (R-ME). Michael is a member of the bars of the District of Columbia and the State of New York.

Roscoe Jones is a partner in Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher’s Washington, DC office, co-chair of the Firm’s Public Policy Practice Group, and a member of the Congressional Investigations Practice Group. Roscoe’s practice focuses on promoting and protecting clients’ interests before the U.S. Congress and the Administration, including providing a range of public policy services to clients such as strategic counseling, advocacy, coalition building, political intelligence gathering, substantive policy expertise, legislative drafting, and message development. Roscoe spent a decade on Capitol Hill as a chief of staff, legislative director and senior counsel advising three US Senators and a member of Congress, including Senators Feinstein, Booker and Leahy and Rep. Spanberger. Roscoe is a member of the bars of the State of Maryland and District of Columbia and admitted to practice before the United States Courts of Appeal for the Fourth, Ninth, and Eleventh Circuits.

Stuart F. Delery is a partner in Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher’s Washington, DC office, where he is a member of the firm’s Litigation Department and Co-Chair of the Crisis Management Practice Group and Administrative Law and Regulatory Practice Group. Prior to re-joining the firm, Stuart served as White House Counsel for President Biden from 2022-2023. As Counsel to the President, he advised the President on the full range of constitutional, statutory, and regulatory legal issues, including on questions of presidential authority, domestic policy, and national security and foreign affairs. He managed responses to high-profile congressional and other investigations, and he assisted the President in nominating and confirming federal judges. Stuart also served as Deputy Counsel to the President from 2021-2022. Stuart is an experienced appellate and district court litigator who brings 30 years of experience at the highest levels of government and the private sector to help clients navigate major matters that present complex legal and reputational risks, particularly matters involving difficult statutory, regulatory and constitutional issues. His practice focuses on representing corporations and individuals in high-stake litigation and investigations that involve the federal government across the spectrum of regulatory litigation and enforcement. Stuart is a member of the District of Columbia bar.

Amanda H. Neely is of counsel in the Washington, D.C. office of Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher and a member of the Public Policy Practice Group and Congressional Investigations Practice Group. Amanda previously served as Director of Governmental Affairs for the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee and General Counsel to Senator Rob Portman (R-OH), Deputy Chief Counsel to the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, and Oversight Counsel on the House Ways and Means Committee. She has represented clients undergoing investigations by congressional committees including the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations and the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee. Amanda is admitted to practice law in the District of Columbia and before the United States Courts of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit and the Eleventh Circuit.

Danny Smith is of counsel in the Washington, D.C. office of Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher and a member of the Public Policy practice group. Danny’s practice focuses on advancing clients’ interests before the U.S. Congress and the Executive Branch. He provides a range of services to clients, including political advice, intelligence gathering, policy expertise, communications guidance, and legislative analysis and drafting. Prior to joining Gibson Dunn, Danny worked for Senator Cory Booker (D-NJ) for nearly a decade, most recently as his Chief Counsel on the Senate Judiciary Committee, Subcommittee on Criminal Justice and Counterterrorism. Danny is admitted to practice law in the District of Columbia and the state of Illinois.

MCLE CREDIT INFORMATION:

This program has been approved for credit in accordance with the requirements of the New York State Continuing Legal Education Board for a maximum of 1.0 credit hour, of which 1.0 credit hour may be applied toward the areas of professional practice requirement. This course is approved for transitional/non-transitional credit.

Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP certifies that this activity has been approved for MCLE credit by the State Bar of California in the amount of 1.0 hour in the General category.

Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP is authorized by the Solicitors Regulation Authority to provide in-house CPD training. This program is approved for CPD credit in the amount of 1.0 hour. Regulated by the Solicitors Regulation Authority (Number 324652).

Neither the Connecticut Judicial Branch nor the Commission on Minimum Continuing Legal Education approve or accredit CLE providers or activities. It is the opinion of this provider that this activity qualifies for up to 1 hour toward your annual CLE requirement in Connecticut, including 0 hour(s) of ethics/professionalism.

Application for approval is pending with the Colorado, Illinois, Texas, Virginia and Washington State Bars.

© 2024 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP. All rights reserved. For contact and other information, please visit us at www.gibsondunn.com.

Attorney Advertising: These materials were prepared for general informational purposes only based on information available at the time of publication and are not intended as, do not constitute, and should not be relied upon as, legal advice or a legal opinion on any specific facts or circumstances. Gibson Dunn (and its affiliates, attorneys, and employees) shall not have any liability in connection with any use of these materials. The sharing of these materials does not establish an attorney-client relationship with the recipient and should not be relied upon as an alternative for advice from qualified counsel. Please note that facts and circumstances may vary, and prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome.

New York partner Karin Portlock and associate Brian Yeh are the authors of “Precedent-Setting Decisions Show the Promise of New York’s Domestic Violence Survivors Justice Act” [PDF] published by the New York Law Journal on March 11, 2024.

Join us for a 60-minute briefing covering key aspects of the SEC’s adoption of the climate change disclosure rule. Gibson Dunn Partners Beth Ising, Tom Kim, Gene Scalia and David Woodcock discuss key aspects of the final rule, what companies need to prioritize in order to prepare for compliance, key implementation challenges and the prospects for litigation.

Topics discussed:

- Primary differences between the proposed and final rules

- Companies and transactions covered by the rule and exemptions, exceptions, and exclusions

- Timing and transition periods

- Open/unresolved issues

- Key implementation and compliance priorities

- Potential litigation

PANELISTS:

Elizabeth Ising is a partner in Gibson Dunn’s Washington, D.C. office and Co-Chair of the firm’s Securities Regulation and Corporate Governance and its ESG (Environmental, Social & Governance) practices. She also is a member of the firm’s Hostile M&A and Shareholder Activism team and Financial Institutions practice group. She advises clients, including public companies and their boards of directors, on corporate governance, securities law and, ESG and sustainability matters and executive compensation best practices and disclosures. Representative matters include advising on Securities and Exchange Commission reporting requirements, proxy disclosures, SASB and TCFD disclosures, director independence matters, proxy advisory services, board and committee charters and governance guidelines and disclosure controls and procedures. Ms. Ising also regularly counsels public companies on shareholder activism issues, including on shareholder proposals and preparing for and responding to hedge fund and corporate governance activism. She also advises non-profit organizations on corporate governance issues.

Thomas J. Kim is a partner in the Washington D.C. office of Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher, LLP, where he is a member of the firm’s Securities Regulation and Corporate Governance Practice Group. Mr. Kim focuses his practice on a broad range of SEC disclosure and regulatory matters, including capital raising and tender offer transactions and shareholder activist situations, as well as corporate governance, environmental social governance and compliance issues. He also advises clients on SEC enforcement investigations – as well as boards of directors and independent board committees on internal investigations – involving disclosure, registration, corporate governance and auditor independence issues. Mr. Kim has extensive experience handling regulatory matters for companies with the SEC, including obtaining no-action and exemptive relief, interpretive guidance and waivers, and responding to disclosures and financial statement reviews by the Division of Corporation Finance. Mr. Kim served at the SEC for six years as the Chief Counsel and Associate Director of the Division of Corporation Finance, and for one year as Counsel to the Chairman.

Eugene Scalia is a partner in the Washington, D.C. office of Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher, co-chair of the firm’s Administrative Law and Regulatory Practice Group, and a senior member of the firm’s Labor and Employment Practice Group and Financial Institutions Practice Group. He returned to the firm after serving as U.S. Secretary of Labor from September 2019 to January 2021. Mr. Scalia has a nationally-prominent practice in two areas: Labor and employment law, and advice and litigation regarding the regulatory obligations of federal administrative agencies. He also has extensive appellate experience. Federal regulatory actions he has challenged include the SEC’s “proxy access” rule; the CFTC’s “position limits’” rule; MetLife’s designation as “too big to fail” by the Financial Services Oversight Council; the Labor Department’s “fiduciary” rule; and OSHA’s “cooperative compliance program.”

David Woodcock is a partner in the Dallas and Washington offices of Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher. He is a co-chair of the firm’s Securities Enforcement Practice Group, and a member of the firm’s Securities Regulation and Corporate Governance, Accounting Firm Advisory and Defense; White Collar Defense and Investigations; Energy, Regulation and Litigation; Securities Litigation; and Oil and Gas Practice Groups. His practice focuses on internal investigations and SEC defense, with a particular emphasis on accounting and financial reporting, corporate compliance, and audit/special committee investigations. Mr. Woodcock regularly advises clients on corporate securities and governance, the role of the board, shareholder activism, and ESG-related issues, including the energy transition, climate disclosures, enterprise risk management practices, cybersecurity, and related U.S./European regulations. He also counsels investment advisors and private equity funds in the context of SEC examinations and investigations, ESG matters, and portfolio due diligence and compliance.

MCLE CREDIT INFORMATION:

This program has been approved for credit in accordance with the requirements of the New York State Continuing Legal Education Board for a maximum of 1.0 credit hour, of which 1.0 credit hour may be applied toward the areas of professional practice requirement. This course is approved for transitional/non-transitional credit.

Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP certifies that this activity has been approved for MCLE credit by the State Bar of California in the amount of 1.0 hour in the General category.

Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP is authorized by the Solicitors Regulation Authority to provide in-house CPD training. This program is approved for CPD credit in the amount of 1.0 hour. Regulated by the Solicitors Regulation Authority (Number 324652).

Neither the Connecticut Judicial Branch nor the Commission on Minimum Continuing Legal Education approve or accredit CLE providers or activities. It is the opinion of this provider that this activity qualifies for up to 1 hour toward your annual CLE requirement in Connecticut, including 0 hour(s) of ethics/professionalism.

Application for approval is pending with the Colorado, Illinois, Texas, Virginia and Washington State Bars.

© 2024 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP. All rights reserved. For contact and other information, please visit us at www.gibsondunn.com.

Attorney Advertising: These materials were prepared for general informational purposes only based on information available at the time of publication and are not intended as, do not constitute, and should not be relied upon as, legal advice or a legal opinion on any specific facts or circumstances. Gibson Dunn (and its affiliates, attorneys, and employees) shall not have any liability in connection with any use of these materials. The sharing of these materials does not establish an attorney-client relationship with the recipient and should not be relied upon as an alternative for advice from qualified counsel. Please note that facts and circumstances may vary, and prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome.

We are pleased to provide you with Gibson Dunn’s ESG update covering the following key developments during February 2024. Please click on the links below for further details.

- Global Reporting Initiative revises biodiversity standards

On January 25, 2024, the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) published a revised biodiversity standard, GRI 101: Biodiversity 2024, which updates and replaces GRI 304: Biodiversity 2016. The standard aims to deliver transparency throughout the supply chain, location-specific reporting on impacts, new disclosures on direct drivers of biodiversity loss and requirements for reporting impacts on society. The standard will come into force on January 1, 2026.

- International Swaps and Derivatives Association Climate Risk Scenario Analysis for the Trading Book – Phase 2

On February 12, 2024, the International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA) published Phase 2 of its “Climate Risk Scenario Analysis for the Trading Book“. This Phase 2 publication follows the development of the conceptual framework published in 2023, which was used to develop three short-term climate scenarios for the trading book – physical, transition and combined. The scenarios are intended to support banks in their climate scenario analysis capabilities and now cover a range of market risk factors, including country and sector specific parameters.

- Loan Market Association issues guidance on external review process for Sustainability-Linked Loans

On January 25, 2024, the Loan Market Association (LMA) issued an updated version of its external review guidance for green, social, and sustainability-linked loans, superseding its 2022 edition. The guidance aims to streamline the process of external reviews in sustainable finance by establishing common terminology and standard review procedures. The guidance also sets out ethical and professional principles for external reviewers, including integrity, objectivity, and professional competence and addresses the organization requirements for review providers. Detailed content guidelines are also provided to promote consistency in terminology usage.

- International Ethics Standards Board for Accountants launches public consultation on new ethical benchmark for sustainability reporting and assurance

The International Ethics Standards Board (IESBA), the independent global standards-setting board, has initiated a consultation on two Exposure Drafts, outlining a suite of global standards on ethical considerations in sustainability reporting and assurance. The first Exposure Draft, International Ethics Standards for Sustainability Assurance (IESSA), revises the existing Code Relating to Sustainability Assurance and Reporting. The second Exposure Draft, Using the Work of an External Expert, proposes an ethical framework for assessing external experts in sustainability matters. These standards aim to establish guidelines for sustainability assurance practitioners and professional accountants involved in reporting, aiming to combat greenwashing and enhance trust in sustainability information.

- ISSB to assess jurisdictions’ level of alignment with standards

The International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) plans to assess the degree of alignment between jurisdictions choosing to implement its disclosure standards on both sustainability (IFRS S1) and the climate (IFRS S2). These measures were announced in the ISSB’s preview document of its Inaugural Jurisdictions Guide. The Guide will aid jurisdictions in their adoption of IFRS S1 and IFRS S2 and also intends to reduce the fragmentation and variation in the adoption of ISSB standards between jurisdictions. ISSB expects the alignment assessment to be part of its future jurisdictional profiles tool, which will describe the broad approach of each jurisdiction and any deviations from ISSB standards. As at December 2023, nearly 400 organizations from 64 different jurisdictions had committed to advancing the adoption or use of the ISSB standards, in addition to 25 stock exchanges and over 40 professional accounting organizations and audit firms.

- UK departs International Energy Charter Treaty

On February 22, 2024, the United Kingdom Government announced that it would leave the Energy Charter Treaty (ECT) after failed efforts to update the Energy Charter Treaty and align it with net zero ambitions. With European Parliament elections in 2024, the modernization of the treaty may be delayed indefinitely. A number of European Union member states, including France, Spain and the Netherlands, have already withdrawn or announced their withdrawal from the treaty.[1]

- UK Financial Conduct Authority launches webpage for sustainability disclosure and labelling regime

As reported in our Winter Edition, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) recently published its policy statement containing rules and guidance on sustainability disclosure requirements and investment labels. On February 2, 2024, the FCA launched a new webpage setting out how firms should consider the regime and the steps to take ahead of the rules coming into effect. The FCA has highlighted that from May 31, 2024, firms are required to ensure that sustainability references are fair, clear and not misleading and proportionate to the sustainability profile of the product and service. Firms subject to the naming and marketing rules for asset managers are not required to meet the additional requirements until December 2, 2024. From July 31, 2024, firms may begin to use a label – though there is no deadline to use labels, firms must ensure that they meet the naming and marketing requirements for products using sustainability-related terms without labels by December 2, 2024.

- Chartered Governance Institute publishes model terms of reference and guidance for ESG committees

The Chartered Governance Institute (CGI, formerly ICSA) published its model terms of reference and guidance for board-level ESG and sustainability committees. Although the new UK Corporate Governance Code (also referred to above) does not require companies to have an ESG committee at board level, the sample terms are designed to assist companies in setting out the scope, roles and responsibilities of board-level ESG and sustainability committees, which can be tailored to the needs of each company. The model terms will also assist companies in highlighting areas which may overlap with the remits of other committees and define the remit of the ESG committee to avoid such overlap.

- Pensions and Lifetime Savings Association updates the Stewardship and Voting Guidelines

The Pensions and Lifetime Savings Association published its updated 2024 Stewardship and Voting Guidelines. The Guidelines have been updated to reflect the 2024 version of the UK Corporate Governance Code published by the Financial Reporting Council (FRC) and related guidance and they provide a framework for pension scheme trustees and investors to hold companies accountable during annual general meetings. The 2024 edition identifies five key themes: social factors, cybersecurity, artificial intelligence, biodiversity, and dual-class asset structures.

- Financial Reporting Council launches review of the UK Stewardship Code 2020

On February 27, 2024, the FRC announced that it would commence a fundamental review of the UK Stewardship Code in accordance with a policy statement it issued on November 7, 2023. The Code’s stated purpose is to set high stewardship standards for asset owners and managers and also includes six principles for service providers. There are currently 273 signatories representing £43.3 trillion assets under management. Given the potential for a fundamental revision of the Code in 2024, the FRC are launching the review process in three phases: a targeted outreach to issuers, asset managers, asset owners and service providers; a public consultation in summer 2024; and the publication of a revised Code in early 2025. The Code will operate as usual throughout the review process. The Stewardship Code was last revised in 2019, taking effect from January 1, 2020. The significant revisions introduced at that time included signatories to integrate stewardship and investment including ESG matters and also required disclosure of important issues for assessing investments including ESG issues.

- New EU regulation on ESG ratings activities

On February 5, 2024, the European Parliament and the European Council announced a provisional agreement on new rules for regulating ESG rating activities by improving transparency and integrity of operations of rating providers and preventing potential conflicts of interest. The provisional agreement provides that EU ratings providers will be authorized and supervised by the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), and third-country ratings providers will need to be registered in the EU’s registry, be recognized on quantitative criteria or obtain an endorsement of their ESG ratings by an EU-authorized ratings provider. A temporary lighter-touch regime would apply for three years for small ESG ratings providers. The provisional agreement remains subject to the European Council and European Parliament’s formal adoption procedure. Once adopted and published in the Official Journal, the regulation will apply 18 months after its entry into force.

- Vote on Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive fails

As reported in our Winter Edition, there was a provisional agreement on the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) in December 2023. The final text of the CSDDD was published on January 30, 2024. On February 28, 2024, the CSDDD failed to secure a qualified majority among EU member states. The CSDDD will need to be renegotiated and voted on by the European Council before it can be voted on by the European Parliament by the March 15, 2024 deadline.

- Internal Market and Environment committees adopt position on how EU firms can validate their green claims

On February 14, 2024, the European Parliament announced that the Internal Market and Environment committees adopted their position on the rules relating to how firms can validate their environmental marketing claims. The rules require companies to seek approval before using environmental marketing claims, which claims are to be assessed by accredited verifiers within 30 days. Companies may be excluded from procurements for non-compliance, or could lose their revenues or face fines of at least 4% of their annual turnover. Confirming the EU ban on greenwashing, the rules specify that companies could still mention offsetting schemes if they have reduced emissions to the extent possible and use these schemes only for residual emissions. The rules are due to be voted on at the next plenary session of the European Parliament.

- European Council and European Parliament strike deal to strengthen EU air quality standards

On February 20, 2024, the European Council announced that the presidency and the European Parliament’s representatives had reached a provisional political agreement on EU air quality standards, with the aim of a zero-pollution objective and net zero by 2050. The provisional agreement will next be submitted to the member states’ representatives in the European Council and to the European Parliament’s environment committee for endorsement. Once approved, it will need to be formally adopted by the European Council and the European Parliament, following which it will be published in the EU’s Official Journal and will enter into force. Following publication, each member state will have two years to transpose the directive into national law.

- Provisional agreement on postponing sustainability reporting standards for listed SMEs and specific sectors

On February 8, 2024, the European Council and the European Parliament announced a provisional agreement to delay by two years the adoption of the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS) for certain sectors, small and medium sized enterprises and certain thirty-country companies, under the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) – which will now be adopted in June 2026. Application to third-country companies remains unchanged otherwise, i.e. reporting obligations under the CSRD and linked ESRS will apply for financial years commencing on or after January 1, 2028. The provisional agreement remains subject to endorsement and formal adoption by both the European Council and European Parliament and publication.

- European Commission recommends 90% net GHG emissions reduction target by 2040

On February 6, 2024, the European Commission published a detailed impact assessment and based on its assessment and under the EU Climate Law framework, it recommended a reduction of 90% net greenhouse gas emissions by 2040 compared to 1990 levels. The EU Climate Law entered into force in July 2021 and enshrined in legislation the EU’s commitment to reach climate neutrality by 2050. The EU Climate Law also requires the European Commission to propose a climate target for 2040 within six months of the first Global Stocktake of the Paris Agreement (which took place in December 2023). Following adoption of the 2040 target, under the next Commission, the target will form the basis for the EU’s new Nationally Determined Contribution under the Paris Agreement.

- European Council and European Parliament reach deal on Net-Zero Industry Act

On February 6, 2024, the European Council and the European Parliament announced a provisional agreement on the Net-Zero Industry Act (NZIA), a regulation aimed at boosting clean technology industries across Europe. Proposed in March 2023 as part of the Green Deal Industrial Plan, the NZIA targets scaling up manufacturing of key technologies for climate neutrality, including solar, wind, batteries, and carbon capture. The NZIA includes streamlined permit procedures for large projects, setting maximum timeframes of 18 months for projects exceeding one gigawatt and 12 months for smaller ventures. It promotes the establishment of net-zero acceleration “valleys” with the aim to create clusters of net-zero industrial activity. The NZIA also contains incentives for green technology purchases and defines sustainability and resilience criteria for public procurement. The provisional agreement remains subject to endorsement and formal adoption by both the European Council and European Parliament and publication.

- Sweden proposes delays to Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive reporting start date

Even as the European Union’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) has been finalized at the EU level, its transposition into national law faces delays in many member states. In Sweden, the government has proposed legislation on February 15, 2024, to postpone CSRD reporting for Swedish companies by one year. The draft proposes applying reporting rules to listed firms with over 500 employees for the fiscal year starting after June 2024, with reporting commencing from the 2025 financial year. This is a deviation from the EU directive, which mandates reporting on data from the 2024 financial year. This proposal remains subject to approval by the Swedish Parliament.

- European Parliament adopts Nature Restoration Law

By a close vote of 329 votes in favour, 275 against and 24 abstentions, on February 27, 2024, the European Parliament adopted a new nature restoration law which sets a target for the European Union (EU) to restore at least 20% of the EU’s land and sea areas by 2030 and all ecosystems which are in need of restoration by 2050. To reach these targets member states will need to restore by 2030 at least 30% of habitats covered by the proposed new law which includes wetlands, grasslands, rivers, lakes, coral beds and forests. The habitat restoration targets increase to 60% by 2040 and 90% by 2050. Member states will also be required to adopt national restoration plans detailing how they intend to achieve these targets. The proposed new law is subject to and conditional upon the European Council adopting the new text which will then be published in the EU Official Journal and enter into force 20 calendar days thereafter.

- Securities and Exchange Commission adopts sweeping new climate disclosure requirements for public companies

On March 6, 2024, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC or Commission), in a divided 3-2 vote along party lines, adopted final rules establishing climate-related disclosure requirements for U.S. public companies and foreign private issuers in their annual reports on Form 10-K and Form 20-F, as well as for companies looking to go public in their Securities Act registration statements. The Commission issued the Proposing Release in March 2022, which we previously summarized here, and received more than 22,500 comments (including more than 4,500 unique letters) from a wide range of individuals and organizations. The Adopting Release is available here and a fact sheet from the SEC is available here. Further details on these new requirements can be found in our recent Client Alert published on March 8, 2024.

- Canadian Sustainability Standards Board launches public consultation on sustainability standards