In response to a claim brought by several environmental advocacy groups (the Associations), which sought to obtain the recognition of the French State’s failure to act in response to climate change, the Administrative Court of Paris (the Court) ruled, for the first time in French law, in a judgment of February 3, 2021, that such a liability action against the State was admissible, that the ecological damage alleged by the Associations was established and that the French State was partially responsible for it. The Court ordered a further investigation in order to determine the measures that it could enjoin the French State to adopt to repair the highlighted damage and prevent its aggravation.

I. Context of the ruling rendered by the Court

The Court’s ruling comes in the wake of several rulings by the Conseil d’Etat, the French highest Administrative Court, which reveal an intensification of control and compliance with the State’s obligations in environmental matters in general, and in connection with climate change in particular.

In a ruling of July 10, 2020, the Conseil d’Etat found that the Government had not taken the measures requested to reduce air pollution in 8 areas in France, as the judge had ordered in a decision of July 12, 2017. To compel it to do so, the Conseil d’Etat imposed a penalty payment of 10 million euros for each semester of delay, the highest amount ever imposed to force the State to enforce a judgement taken by the Administrative judge (CE, Ass., 10 July 2020, Les Amis de la Terre, no. 428409).

In a Grande Synthe ruling of November 19, 2020, the Conseil d’Etat ruled for the first time on a case concerning compliance with commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Indeed, the city of Grande-Synthe referred the matter to the Conseil d’Etat after the refusal of the Government to comply with its request for additional measures to be taken to meet the goals resulting from the Paris Agreement. The Conseil d’Etat first ruled that the request of the city, a coastal city particularly exposed to the effects of climate change, was admissible. On the merits, the Conseil d’Etat noted, firstly, that although France has committed to reducing its emissions by 40% by 2030, in recent years it has regularly exceeded the emission ceilings it had set itself and, secondly, that the decree of April 21, 2020 postponed most of the reduction efforts beyond 2020. According to the High Administrative Court, it is not necessary to wait until the 2030 deadline to exercise control over the State’s actions since the control of the trajectory that the State has set itself is relevant in ecological matters. Before ruling definitively on the request, the Conseil d’Etat asked the Government to justify, within three months, that its refusal to take additional measures is compatible with compliance with the reduction trajectory chosen to achieve the objectives set for 2030. If the justifications provided by the Government are not sufficient, the Conseil d’Etat may then grant the municipality’s request and cancel the refusal to take additional measures to comply with the planned trajectory to achieve the -40% target by 2030 (EC, November 19, 2020, Commune de Grande-Synthe et al., no. 427301), or even impose obligations on the French State. According to the information provided by representatives of the Conseil d’Etat, the decision could be taken before Summer 2021.

Moreover, in a ruling of January 29, 2021, the Versailles Administrative Court of Appeal referred a question to the Court of Justice of the European Union to determine whether the rules of the European Union law should be interpreted as opening up to individuals, in the event of a sufficiently serious breach by a European Union Member State of the obligations resulting therefrom, a right to obtain from the Member State in question compensation for damage affecting their health that has a direct and certain causal link with the deterioration of air quality (CAA Versailles, January 29, 2021, no. 18VE01431).

II. Reasoning steps followed by the Court

First, the Court ruled on the admissibility of the action for compensation for ecological damage brought by the Associations against the French State. In order to recognize the Associations’ status as victims, the Court had to acknowledge the existence of a fault, damage and a causal link between the fault and the damage.

First of all, it recalled that in application of article 1246 of the French Civil Code “Any person responsible for ecological damage is required to repair it”. Implicitly, the Court considered that this provision is applicable to the State. Article 1248 of the French Civil Code provides that “The action for compensation for ecological damage is open to any person having the capacity and interest to act, [such as] associations approved or created for at least five years at the date of the institution of proceedings which have as their purpose the protection of nature and the defense of the environment”. After having examined the purpose in the Associations’ by-laws, which mention the environment protection and sometimes explicitly the fight against climate change, the Court considered that their liability action was admissible.

Second, the Court had to rule on the existence of ecological damage, bearing in mind that such damage consists of “a non-negligible damage to the elements or functions of ecosystems or to the collective benefits derived by mankind from the environment” (Article 1247 of the French Civil Code). In this respect, it should be emphasized that the Conseil Constitutionnel considered that the legislature could validly exclude from the set-up compensation mechanism, the compensation for negligible damage to the elements, functions and collective benefits derived by mankind from the environment (Decision no. 2020-881 QPC of February 5, 2021). Consequently, it is up to the courts to determine, on a case-by-case basis, according to the facts of the case, what the notion of “non-negligible damage” covers.

In order to characterize the existence of non-negligible damage, the Court first relied on the work of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), from which it concluded “that the constant increase in the average global temperature of the Earth, which has now reached 1°C compared to the pre-industrial era, is due mainly to greenhouse gas emissions [resulting from human activity]. This increase, responsible for a modification of the atmosphere and its ecological functions, has already caused, among other things, the accelerated melting of continental ice and permafrost and the warming of the oceans, resulting in an accelerating rise in sea level”.

It also drew on the work of the National Observatory on the Effects of Global Warming, a body attached to the Ministry of Ecological Transition and responsible in particular for describing, through a certain number of indicators, the state of the climate and its impacts on the entire national territory. The Court found that “in France, the increase in average temperature, which for the 2000-2009 decade amounts to 1.14°C compared to the 1960-1990 period, is causing an acceleration in the loss of glacier mass, particularly since 2003, the aggravation of coastal erosion, which affects a quarter of French coasts, and the risk of submersion, which poses serious threats to the biodiversity of glaciers and the coastline, is leading to an increase in extreme climatic phenomena, such as heat waves, droughts, forest fires, extreme rainfalls, floods and hurricanes, which are risks to which 62% of the French population is highly exposed, and is contributing to the increase in ozone pollution and the spread of insects that are vectors of infectious agents such as dengue fever or chikungunya”.

In light of all these elements, the Court considered that the ecological damage claimed by the Associations had to be considered as established.

Third, the Court had to identify the obligations of the States in responding to climate change in order to, in a second stage, rule on possible breaches in relation to these obligations.

The Court considered that it arose in particular from the provisions of the Paris Agreement of December 12, 2015, as well as from European and national standards relating to the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, that the French State had committed to take effective action against climate change in order to limit its causes and mitigate its harmful consequences. From this perspective, the Court recalled that the French State had chosen to exercise “its regulatory power, in particular by conducting a public policy to reduce greenhouse gas emissions emitted from the national territory, by which it undertook to achieve, at specific and successive deadlines, a certain number of objectives in this area”.

The Court then examined compliance with the greenhouse gas emission reduction trajectories that the State had set itself in order to determine whether it had failed to meet its obligations. To do so, it relied in particular on the annual reports published in June 2019 and July 2020 by the High Council for the Climate, an independent body whose mission is to issue opinions and recommendations on the implementation of public policies and measures to reduce greenhouse gas emissions of France. In its two reports, the High Council for the Climate noted that “the actions of France are not yet commensurate with the challenges and objectives it has set itself” and noted the lack of substantial reduction in all the economic sectors concerned, particularly in transportation, agriculture, construction and industry sectors.

The Court concluded that the French State should be regarded as having failed to carry out the actions that it had itself recognized as likely to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The guilty failure to meet its commitments was thus characterized, as was the causal link between that failure and the ecological damage previously identified. The Court therefore considered that part of that damage was attributable to the failure of the French State to act.

Fourth, the Court had to rule on the modalities of reparation of the ecological damage. Under the terms of the law, this was to be carried out primarily in kind. It is only in the event of impossibility or inadequacy of the reparation measures that the judge sentences the liable person to pay damages to the plaintiff, such damage being allocated to the reparation of the environment.

The Court considered that in the state of the investigation of the case, it was not in a position to determine the measures “that must be ordered to the State” to repair the observed damage or to prevent its future aggravation. He therefore prescribed a further two-month investigation in order to identify the measures in question.

Fifth, it sentenced the State to pay each of the Associations a symbolic sum of one euro as compensation for the moral prejudice it had caused them by not respecting the goals of reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

III. Follow-up to the Court’s ruling

The Court’s ruling, which sentences the State for not having implemented the necessary measures to achieve the greenhouse gas emission reduction targets, is a landmark decision in French law.

The second ruling that will be rendered following the two-month additional investigation ordered by the Court could constitute another historic decision if the Court were to enjoin the State – as the terms of the Ruling seem to imply – to implement a number of specific measures aimed at achieving the expected reduction targets, if necessary within a set timeframe. When this judgment comes into effect, possibly before the 2021 Summer, it will then be necessary to examine the impact of the measures that would thus be ordered on the economic sectors and companies likely to be affected.

At this stage of the proceedings, it is not possible to determine whether or not the French State will decide to appeal the ruling rendered by the Court to the Administrative Court of Appeal of Paris. If the latter were to uphold the ruling, the French State could then appeal to the Conseil d’Etat. A final decision on the issue at stake in this case could thus only be made in several years’ time.

The Court’s ruling could also have the immediate effect of modifying the provisions of the “Bill to combat climate change and strengthen resilience to its effects” which will be debated in the French Parliament from the end of March 2021. During the discussion, parliamentarians in favor of strengthening the provisions of this law could rely on the Court’s ruling to motivate and justify their position.

The following Gibson Dunn attorneys assisted in preparing this client update: Nicolas Autet and Gregory Marson.

Gibson Dunn’s lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding these developments. Please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, the authors, or any of the following lawyers in Paris by phone (+33 1 56 43 13 00) or by email:

Nicolas Autet ([email protected])

Gregory Marson ([email protected])

Nicolas Baverez ([email protected])

Maïwenn Béas ([email protected])

© 2021 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP

Attorney Advertising: The enclosed materials have been prepared for general informational purposes only and are not intended as legal advice.

London partners Susy Bullock, Matthew Nunan, Michelle Kirschner and James Cox are the authors of “Big data, ethics and financial services: risks, controls and opportunities,” [PDF] published by the Butterworths Journal of International Banking and Financial Law in February 2021.

New York partner Avi Weitzman and of counsel Tina Samanta are the authors of “Congress Codifies SEC Disgorgement Remedy in Military Spending Bill,” [PDF] published by Wall Street Journal in February 2021. The material is used with permission from Thomson Reuters.

Our panelists discuss significant recent developments and forecast what to expect from the new U.S. presidential administration on topics ranging from data privacy and cybersecurity to antitrust, corporate governance, international trade, money laundering, securities fraud, white collar defense and investigations, and more. Our panelists also will provide practical tips for identifying and addressing key compliance risks and strengthening corporate compliance programs.

Topics to be discussed include:

- Global Enforcement and Regulatory Developments

- The Biden Administration’s Expected Approach to Enforcement and Regulation

- Practical Recommendations for Improving Corporate Compliance

- DOJ and SEC Priorities, Policies, and Penalties

- Update on Key Governance Issues and Regulatory Requirements

View Slides (PDF)

MODERATOR:

Joseph Warin, a partner in Washington, D.C., is Co-Chair of the firm’s White Collar Defense and Investigations practice and former Assistant U.S. Attorney in Washington, D.C. Mr. Warin is consistently recognized annually in the top-tier by Chambers USA, Chambers Global, and Chambers Latin Americafor his FCPA, fraud and corporate investigations acumen. In 2018 Mr. Warin was selected by Chambers USAas a “Star” in FCPA, and “a “Leading Lawyer” in the nation in Securities Regulation: Enforcement. Global Investigations Review reported that Mr. Warin has now advised on more FCPA resolutions than any other lawyer since 2008. Who’s Who Legal and Global Investigations Review named Mr. Warin to their 2016 list of World’s Ten-Most Highly Regarded Investigations Lawyers based on a survey of clients and peers, noting that he was one of the “most highly nominated practitioners,” and a “’favourite’ of audit and special committees of public companies.” Mr. Warin has handled cases and investigations in more than 40 states and dozens of countries. His credibility at DOJ and the SEC is unsurpassed among private practitioners — a reputation based in large part on his experience as the only person ever to serve as a compliance monitor or counsel to the compliance monitor in three separate FCPA monitorships, pursuant to settlements with the SEC and DOJ: Statoil ASA (2007-2009); Siemens AG (2009-2012); and Alliance One International (2011-2013).

PANELISTS:

Roscoe Jones, a counsel in Washington, D.C., is a member of the firm’s Public Policy, Congressional Investigations, and Crisis Management groups. Mr. Jones formerly served as Chief of Staff to U.S. Representative Abigail Spanberger, Legislative Director to U.S. Senator Dianne Feinstein, and Senior Counsel to U.S. Senator Cory Booker, among other high-level roles on Capitol Hill.

Thomas Kim, a partner in Washington, D.C., is a member of the firm’s Securities Regulation and Corporate Governance Practice Group. Mr. Kim focuses his practice on advising companies, underwriters and boards of directors on registered and exempt capital markets transactions, SEC regulatory and reporting issues, and corporate governance, as well as on general corporate and securities matters. Mr. Kim served for six years as the Chief Counsel and Associate Director of the Division of Corporation Finance at the SEC.

Kristen Limarzi, a partner in Washington, D.C., focuses on investigations, litigation, and counseling on antitrust merger and conduct matters, as well as appellate and civil litigation. Ms. Limarzi previously served as the Chief of the Appellate Section of the U.S. Department of Justice’s Antitrust Division, where she led a team of more than a dozen professionals litigating appeals in the Division’s civil and criminal enforcement actions and participating as amicus curiae in private antitrust actions.

Jason J. Mendro, a partner in Washington, D.C., represents clients in wide-ranging shareholder disputes, including securities class actions, challenges to mergers and acquisitions, and derivative lawsuits alleging breaches of fiduciary duties. Mr. Mendro also advises boards of directors and special litigation committees in conducting internal investigations and addressing shareholder litigation demands. He has earned national recognition, being named “Litigator of the Week” by The American Lawyer and a “Rising Star” by Law360 and Super Lawyers.

Adam M. Smith, a partner in Washington, D.C., was the Senior Advisor to the Director of the U.S. Treasury Department’s OFAC and the Director for Multilateral Affairs on the National Security Council. His practice focuses on international trade compliance and white collar investigations, including with respect to federal and state economic sanctions enforcement, the FCPA, embargoes, and export controls. He routinely advises multi-national corporations regarding regulatory aspects of international business.

Lori Zyskowski, a partner in New York, is Co-Chair of the firm’s Securities Regulation and Corporate Governance practice. She was previously Executive Counsel, Corporate, Securities & Finance at GE. She advises clients, including public companies and their boards of directors, on a wide variety of corporate governance and securities disclosure issues, and provides a unique perspective gained from over 12 years working in-house at S&P 500 corporations.

Lora MacDonald, an associate in Washington, D.C., practices in the firm’s Litigation Department, focusing on white collar criminal defense and internal investigations. Ms. MacDonald has experience conducting internal investigations and advising clients on compliance with the FCPA and other anti-corruption laws. She also assists clients under investigation by the World Bank Integrity Vice Presidency and companies already subject to World Bank sanction.

MCLE CREDIT INFORMATION:

This program has been approved for credit in accordance with the requirements of the New York State Continuing Legal Education Board for a maximum of 3.0 credit hours, of which 3.0 credit hours may be applied toward the areas of professional practice requirement.

This course is approved for transitional/non-transitional credit. Attorneys seeking New York credit must obtain an Affirmation Form prior to watching the archived version of this webcast. Please contact [email protected] to request the MCLE form.

Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP certifies that this activity has been approved for MCLE credit by the State Bar of California in the amount of 2.5 hours.

California attorneys may claim “self-study” credit for viewing the archived version of this webcast. No certificate of attendance is required for California “self-study” credit.

On February 18, 2021, the U.S. Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), an agency of the Treasury Department that administers and enforces U.S. economic and trade sanctions, issued an enforcement release of a settlement agreement with BitPay, Inc. (BitPay) for apparent violations relating to Bitpay’s payment processing solution that allows merchants to accept digital currency as payment for goods and services.[1] OFAC found that BitPay allowed users apparently located in sanctioned countries and areas to transact with merchants in the United States and elsewhere using the BitPay platform, even though BitPay had Internet Protocol (IP) address data for those users. The users in sanctioned countries were not BitPay’s direct customers, but rather its customer’s customers (in this case the merchants’ customers).

The BitPay action follows an OFAC December 30, 2020 enforcement release of a settlement agreement with BitGo, Inc. (BitGo), also for apparent violations related to digital currency transactions.[2] BitGo offers, among other services, non-custodial secure digital wallet management services, and OFAC found that BitGo failed to prevent users located in the Crimea region of Ukraine, Cuba, Iran, Sudan and Syria from using these services. OFAC determined that BitGo had reason to know the location of these users based on IP address data associated with the devices used to log into its platform.

This Alert discusses these developments.

I. OFAC’s Enforcement Against BitGo

BitGo, which was founded in 2013 and is headquartered in Palo Alto, California, is self-described as “the leader in digital asset financial services, providing institutional investors with liquidity, custody, and security solutions.”[3] As OFAC explained in its enforcement release, the company agreed to remit $98,830 to settle potential civil liability related to 183 apparent violations of multiple sanctions programs. OFAC specifically claimed that between 2015 and 2019, deficiencies in BitGo’s sanctions compliance procedures led to BitGo’s failing to prevent individuals located in the Crimea region of Ukraine, Cuba, Iran, Sudan, and Syria from using BitGo’s non-custodial secure digital wallet management service despite having reason to know that these individuals were located in sanctioned jurisdictions. Reason to know was based on BitGo’s having IP address data associated with the devices that these individuals used to log in to the BitGo platform. According to OFAC, BitGo processed 183 digital currency transactions on behalf of these individuals, totaling $9,127.79.

According to the OFAC release, prior to April 2018, BitGo had allowed individual users of its digital wallet management services to open an account by providing only a name and email address. In April 2018, BitGo supplemented this practice by requiring new users to verify the country in which they were located, with BitGo generally relying on the user’s attestation regarding his or her location rather than performing additional verification or diligence on the user’s location. In January 2020, however, BitGo discovered the apparent violations of multiple sanctions compliance programs. It thereupon implemented a new OFAC Sanctions Compliance Policy and undertook significant remedial measures. This new policy included appointing a Chief Compliance Officer, blocking IP addresses for sanctioned jurisdictions, and keeping all financial records and documentation related to sanctions compliance efforts.

II. OFAC’s Enforcement Against BitPay

BitPay, which was founded in 2011 and is headquartered in Atlanta, Georgia, provides digital asset management and payment services that enable consumers “to turn digital assets into dollars for spending at tens of thousands of businesses.”[4] As OFAC explained in its enforcement release, BitPay agreed to remit $507,375 to settle potential civil liability related to 2,102 apparent violations of multiple sanctions programs. OFAC specifically claimed that between 2013 and 2018, deficiencies in BitPay’s sanctions compliance procedures led to BitPay’s allowing individuals who appear to have been located in the Crimea region of Ukraine, Cuba, North Korea, Iran, Sudan, and Syria to transact with merchants in the United States and elsewhere using digital currency on BitPay’s platform despite BitPay having location data, including IP addresses, about those individuals prior to effecting the transactions.

BitPay allegedly “received digital currency payments on behalf of its merchant customers from those merchants’ buyers who were located in sanctioned jurisdictions, converted the digital currency to fiat currency, and then relayed that currency to its merchants.” According to OFAC, BitPay processed 2,102 such transactions totaling $128,582.61. Although BitPay had (i) screened its direct customers (i.e., its merchant customers) against OFAC’s List of Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons and (ii) conducted due diligence on the merchants to ensure they were not located in sanctioned jurisdictions, BitPay failed to screen location data that it obtained about its merchants’ buyers—BitPay had begun receiving buyers’ IP address data in November 2017, and prior to that received information that included buyers’ addresses and phone numbers. BitPay had implemented sanctions compliance controls as early as 2013, including conducting due diligence and sanctions screening on its merchants, and formalized its sanctions compliance program in 2014. However, following its apparent violations, BitPay supplemented its program with the following:

- Blocking IP addresses that appear to originate in Cuba, Iran, North Korea, and Syria from connecting to the BitPay website or from viewing any instructions on how to make payment;

- Checking physical and email addresses of merchants’ buyers when provided by the merchants to prevent completion of an invoice from the merchant if BitPay identifies a sanctioned jurisdiction address or email top-level domain; and

- Launching “BitPay ID,” a new customer identification tool that is mandatory for merchants’ buyers who wish to pay a BitPay invoice equal to or above $3,000. As part of BitPay ID, the merchant’s customer must provide an email address, proof of identification/photo ID, and a selfie photo.

III. Conclusion

The major takeaway from these two enforcement cases is that OFAC expects digital asset companies to use IP address data or other location data—even for their customers’ customers—to screen that location information as part of their OFAC compliance function. OFAC will undoubtedly be considering whether a company has screened such information in assessing whether to impose a penalty. More guidance on OFAC’s perspective on the essential components of a sanctions compliance program is available in A Framework for OFAC Compliance Commitments, which OFAC published in May 2019. In addition, we anticipate ongoing scrutiny by OFAC of digital asset companies, given that key Treasury Department policymakers continue to express concerns about digital assets being used to avoid economic sanctions and anti-money laundering compliance.[5]

_____________________

[1] OFAC Enters Into $507,375 Settlement with BitPay, Inc. for Apparent Violations of Multiple Sanctions Programs Related to Digital Currency Transactions (Feb. 18, 2021), available at https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/126/20210218_bp.pdf.

[2] OFAC Enters Into $98,830 Settlement with BitGo, Inc. for Apparent Violations of Multiple Sanctions Programs Related to Digital Currency Transactions (Dec. 30, 2020), available at https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/126/20201230_bitgo.pdf.

[3] See BitGo Announces $16 Billion in Assets Under Custody (December 21, 2020), available at https://www.bitgo.com/newsroom/press-releases/bitgo-announces-16-billion-in-assets-under-custody.

[4] See For a Limited Time BitPay and Simplex Partner to Offer Zero Fees on Crypto Purchases for All of Europe (EEA) (February 15, 2021), available at https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20210215005244/en/For-a-Limited-Time-BitPay-and-Simplex-Partner-to-Offer-Zero-Fees-on-Crypto-Purchases-for-All-of-Europe-EEA.

[5] U.S. Treasury Department Holds Financial Sector Innovation Policy Roundtable (February 10, 2021), available at https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy0023.

The following Gibson Dunn lawyers assisted in preparing this client update: Arthur Long, Judith Alison Lee, Jeffrey Steiner and Rama Douglas.

Gibson Dunn’s lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding these developments. Please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, the authors, or any of the following members of the firm’s Financial Institutions, Derivatives, or International Trade practice groups:

Financial Institutions and Derivatives Groups:

Matthew L. Biben – New York (+1 212-351-6300, [email protected])

Michael D. Bopp – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-955-8256, [email protected])

Stephanie Brooker – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3502, [email protected])

M. Kendall Day – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-955-8220, [email protected])

Mylan L. Denerstein – New York (+1 212-351- 3850, [email protected])

Michelle M. Kirschner – London (+44 (0) 20 7071 4212, [email protected])

Arthur S. Long – New York (+1 212-351-2426, [email protected])

Jeffrey L. Steiner – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3632, [email protected])

International Trade Group:

Judith Alison Lee – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3591, [email protected])

Adam M. Smith – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3547, [email protected])

© 2021 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP

Attorney Advertising: The enclosed materials have been prepared for general informational purposes only and are not intended as legal advice.

New York partner Avi Weitzman and associate David Salant are the authors of “The Due Process Protections Act: Congress Directs Judges to More Actively Prevent and Remedy Prosecutorial Brady Violations,” [PDF] published by the Washington Legal Foundation on February 19, 2021.

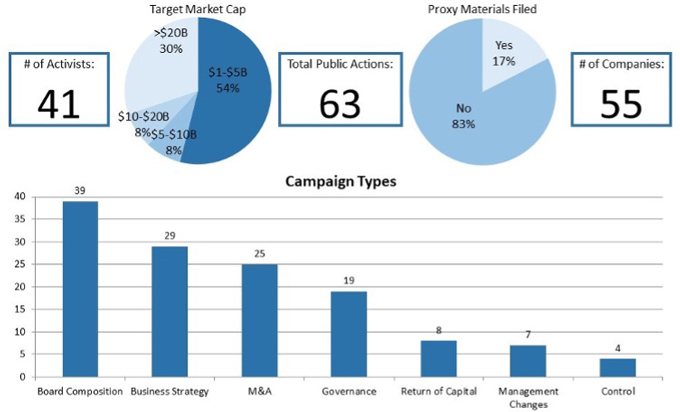

This Client Alert provides an update on shareholder activism activity involving NYSE- and Nasdaq-listed companies with equity market capitalizations in excess of $1 billion and below $100 billion (as of the last date of trading in 2020) during the second half of 2020. Announced shareholder activist activity increased relative to the second half of 2019. The number of public activist actions (35 vs. 24), activist investors taking actions (31 vs. 17) and companies targeted by such actions (33 vs. 23) each increased substantially. On a full-year basis, however, owing to the market disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, 2020 represented a modest slowdown in activism versus 2019, as reflected in the number of public activist actions (63 vs. 75), activist investors taking actions (41 vs. 49) and companies targeted by such actions (55 vs. 64). During the period spanning July 1, 2020 to December 31, 2020, two of the 39 companies targeted by activists—CoreLogic, Inc. and Monmouth Real Estate Investment Corporation—were the subject of multiple campaigns. CoreLogic, Inc. was the subject of an activist campaign led by Cannae Holdings and Senator Investment Group; their efforts, in turn, ultimately drew the support of Pentwater Capital Management LP. In addition, certain activists launched multiple campaigns during the second half of 2020: Elliott Management, NorthStar Asset Management and Starboard Value. These three activists represented 23% of the total public activist actions that began during the second half of 2020.

*Study covers selected activist campaigns involving NYSE- and Nasdaq-traded companies with equity market capitalizations of greater than $1 billion as of December 31, 2020 (unless company is no longer listed).

**All data is derived from the data compiled from the campaigns studied for the 2020 Year-End Activism Update.

Additional statistical analyses may be found in the complete Activism Update linked below.

The rationales for activist campaigns during the second half of 2020 changed in certain respects relative to the first half of 2020. Over both periods, board composition and business strategy represented leading rationales animating shareholder activism campaigns, representing 55% of rationales in the first half of 2020 and 49% of rationales in the second half of 2020. M&A (which includes advocacy for or against spin-offs, acquisitions and sales) took on increased importance; the frequency with which M&A animated activist campaigns rose from 9% in the first half of 2020 to 19% in the second half of 2020. At the opposite end of the spectrum, management changes, return of capital and control remained the most infrequently cited rationale for activist campaigns. (Note that the above-referenced percentages total over 100%, as certain activist campaigns had multiple rationales.) These themes are all broadly consistent with those observed in 2019. Proxy solicitation occurred in 14% of campaigns for the second half of 2020 and for 17% of campaigns in 2020 overall. These figures represent modest declines relative to 2019, in which proxy materials were filed in approximately 30% of activist campaigns for the entire year.

Eight settlement agreements pertaining to shareholder activism activity were filed during the second half of 2020 and only 17 were filed for the entire year, which continues a trend of diminution (relative to 22 agreements filed in 2019 and 30 agreements filed in 2018). Those settlement agreements that were filed had many of the same features noted in prior reviews, however, including voting agreements and standstill periods as well as non-disparagement covenants and minimum and/or maximum share ownership covenants. Expense reimbursement provisions were included in half of those agreements reviewed, which is consistent with historical trends. We delve further into the data and the details in the latter half of this Client Alert. We hope you find Gibson Dunn’s 2020 Year-End Activism Update informative. If you have any questions, please reach out to a member of your Gibson Dunn team.

Gibson Dunn’s lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding the issues discussed in this publication. For further information, please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, or any of the following authors in the firm’s New York office:

Barbara L. Becker (+1 212.351.4062, [email protected])

Dennis J. Friedman (+1 212.351.3900, [email protected])

Richard J. Birns (+1 212.351.4032, [email protected])

Eduardo Gallardo (+1 212.351.3847, [email protected])

Andrew Kaplan (+1 212.351.4064, [email protected])

Saee Muzumdar (+1 212.351.3966, [email protected])

Daniel S. Alterbaum (+1 212.351.4084, [email protected])

Lisa Phua (+1 212.351.2327, [email protected])

Please also feel free to contact any of the following practice group leaders and members:

Mergers and Acquisitions Group:

Jeffrey A. Chapman – Dallas (+1 214.698.3120, [email protected])

Stephen I. Glover – Washington, D.C. (+1 202.955.8593, [email protected])

Jonathan K. Layne – Los Angeles (+1 310.552.8641, [email protected])

Securities Regulation and Corporate Governance Group:

Brian J. Lane – Washington, D.C. (+1 202.887.3646, [email protected])

Ronald O. Mueller – Washington, D.C. (+1 202.955.8671, [email protected])

James J. Moloney – Orange County, CA (+1 949.451.4343, [email protected])

Elizabeth Ising – Washington, D.C. (+1 202.955.8287, [email protected])

Lori Zyskowski – New York (+1 212.351.2309, [email protected])

© 2021 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP

Attorney Advertising: The enclosed materials have been prepared for general informational purposes only and are not intended as legal advice.

Los Angeles partner Michael Farhang is the author of “A setback for the broadening of insider trading liability,” [PDF] published by the Daily Journal on February 18, 2021.

Washington, D.C. partner Stacie Fletcher, Los Angeles partner Abbey Hudson and Washington, D.C. associate Rachel Levick Corley are the authors of “3 Key Environmental Takeaways From Biden’s First 30 Days,” [PDF] published by Law360 on February 17, 2021.

I. Introduction

At the end of the Trump Administration, the bipartisan Internet of Things (IoT) Cybersecurity Improvement Act of 2020 (“the Act”) was enacted after passing the House of Representatives on a suspension of the rules and the Senate by unanimous consent. The Act requires agencies to increase cybersecurity for IoT devices owned or controlled by the federal government. Despite its seemingly limited scope, the Act is anticipated to have a significant, wide-ranging impact on the general development and manufacturing of IoT devices.

The Internet of Things is the “extension of internet connectivity into physical devices and everyday objects.”[1] It covers devices — often labeled as “smart devices” — that have a network interface, function independently, and interact directly with the physical world.”[2] While the Act’s definition of IoT devices expressly excludes conventional information technology devices (for example, computers, laptops, tablets, and smartphones),[3] it extends to a variety of sensors, actuators, and processors used by the federal government.[4] Agencies have reported using IoT devices for controlling or monitoring equipment, tracking physical assets, providing surveillance, collecting environmental data, monitoring health and biometrics, and many other purposes.[5] This usage is likely to expand as over 85% of federal agencies either are currently employing IoT devices or plan to do so in the next five years, further elevating the significance of the Act.[6]

Although the Act is focused on federal government IoT devices, it has significant implications for the widespread and growing corporate and private consumer use of these devices. The North American market for IoT devices has been valued around $95 billion in 2018 and forecasted to be $340 billion by 2024.[7] This has been driven by about 2.3 billion IoT device connections in 2018, which are expected to reach almost 6 billion by 2025.[8] The global market for these devices is similarly expected to grow substantially, with an approximately 37% increase from 2017 to over $1.5 trillion by 2025.[9] This global number of active IoT devices is projected to rise from 9.9 billion in 2019 to 21.5 billion in 2025.[10] As federal standards are often a baseline or guide for industries, such as for product manufacturers seeking uniformity and efficiency, the measures set pursuant to the IoT Cybersecurity Improvement Act should be closely monitored by all industry stakeholders.

II. Provisions of the Act

The Act has a few primary components for strengthening IoT cybersecurity and the government’s critical technology infrastructure. First, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) is tasked with developing security standards and guidelines for the appropriate use and management of all IoT devices owned or controlled by the federal government and connected to its information systems.[11] This includes establishing minimum information security requirements for managing cybersecurity risks associated with these devices. In formulating these guidelines, NIST must consider its current efforts regarding the security of IoT devices, as well as the “relevant standards, guidelines, and best practices developed by the private sector, agencies, and public-private partnerships.”[12] Within 90 days, NIST will promulgate the standards and guidelines for the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) to implement, under consultation with the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) as necessary, by reviewing agency information security policies and principles for consistency.[13] Devices that are a part of a national security system, however, are exempt from review by OMB.[14]

A second set of the Act’s provisions govern the disclosure process among federal agencies and contractors regarding information security vulnerabilities. Again, NIST is tasked with creating guidelines, within 180 days, to advise agencies and contractors on measures for receiving, reporting, and disseminating information about security vulnerabilities and their resolution.[15] These guidelines will also be formulated by considering non-governmental sources in order to better align them with industry best practices, international standards, and “any other appropriate, relevant, and widely-used standard.”[16] Similarly, these measures will be implemented by OMB in consultation with DHS, who will also provide operational and technical assistance to agencies.[17]

While the previous components will set the baseline for federal IoT cybersecurity standards, the real bite of the Act comes from its prohibition on agencies from procuring, obtaining, or using any IoT devices that would render an agency non-compliant with NIST’s standards and guidelines.[18] These determinations will be made by an agency’s Chief Information Officer (CIO) upon reviewing its government contracts involving IoT devices.[19] Agency heads have some flexibility to waive this prohibition, however, if the agency CIO determines that the device is necessary for either national security interests or research purposes, or if it is secured using alternative and effective methods based on the function of the device.[20] IoT device manufacturers currently supplying or vying for government contracts should ensure cybersecurity compliance by the time that the prohibition takes effect in December 2022.[21] All other IoT device manufacturers, including those that focus entirely on private consumers, would also be well-advised to carefully consider the requirements established pursuant to the Act, as the U.S. government is the single largest consumer in the world and creates standards that are likely to have trickle-down effects on the industry as a whole.

Lastly, a few of the Act’s remaining provisions require the Government Accountability Office (GAO) to submit reports to Congress on the processes established by the Act and broader IoT efforts.[22]

III. Draft Guidance by NIST

Since the Act was passed, NIST has already started carrying out its mandate by releasing four new public drafts of its guidance on IoT cybersecurity. The first document — Draft NIST SP 800-213 — is a part of the Special Publication 800-series developed to address and support the security and privacy needs of U.S. government information systems.[23] This draft provides guidance for federal agencies to establish and evaluate the security capabilities required in their IoT devices.[24] It includes background information on the security challenges posed by IoT devices, as well as various considerations for managing risks and vulnerabilities.

The remaining three draft documents — NIST Interagency Reports (NISTIRs) 8259B, 8259C, and 8259D — build upon a series directed at establishing baselines for IoT device manufacturers to identify and meet the security requirements expected by customers.[25] This 8259-series currently contains a total of five documents that together discuss foundational cybersecurity activities, baselines for cybersecurity and non-technical capabilities, and a process for developing customized cybersecurity profiles to meet the needs of specific IoT device customers or applications.[26] The series contains an example of the process applied to create a profile on the federal government customer, which can also serve as a guide for manufacturers to profile other customers and markets. On January 7, 2021, NIST also published a report — NISTIR 8322 — summarizing the feedback received from its July 2020 workshop on the creation of the federal profile of IoT device cybersecurity requirements.[27]

Since releasing the drafts, NIST has opened a public comment period for soliciting community input. This comment period was recently extended to February 26, 2021. Any IoT stakeholders should consider reviewing the documents and providing feedback to NIST. The Act directs NIST to release finalized standards and guidelines by March 4, 2021, for the appropriate use and management of government IoT devices by federal agencies.[28] NIST must also establish its guidelines for receiving, reporting, and disseminating information about security vulnerabilities and their resolution by June 2, 2021.[29]

IV. Context and Effect

The IoT Cybersecurity Improvement Act of 2020 will undoubtedly help strengthen critical technology infrastructure, although how effective it will be at preventing attacks remains to be seen. The Act comes at a time when addressing information security vulnerabilities in the government’s contractor supply chain is as pressing as ever.

Some IoT devices released into consumer markets have turned out to have insufficient cybersecurity protections, as cyber criminals have found ways to exploit the trade-offs between cost, expediency, and security made by manufacturers to meet rapidly evolving consumer demands. Cyber criminals have taken advantage of IoT vulnerabilities to access systems and data, as well as to commit denial-of-service or ransomware attacks. For example, the infamous Mirai botnet used insecure IoT devices to conduct a massive distributed denial-of-service attack in 2016 that took down the websites of multiple major U.S. companies.[30] This issue has only intensified as the global coronavirus pandemic has driven further reliance on IoT devices. A recent report indicated that the share of IoT devices being infected has doubled in 2020 compared to other similarly connected devices.[31]

Very few states have enacted legislation requiring IoT device manufacturers to meet certain cybersecurity standards. These states include California and Oregon, both of which mandate manufacturers to equip devices with “reasonable security feature[s].”[32] Beyond the U.S., Europe has a baseline cybersecurity standard for consumer IoT devices, which was released by the European Telecommunications Standards Institute in June 2020,[33] as well as guidelines by the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA) for securing supply chain processes used to develop IoT products.[34] The U.K. has also taken recent regulatory steps to directly address IoT device cybersecurity.[35] As the first federal legislation in the U.S. targeting IoT security, the IoT Cybersecurity Improvement Act is a welcome addition to the country’s historically sectored and disparate legal landscape for information security and data privacy.

The Act’s improvements for federal IoT device security are anticipated to similarly strengthen and push forward protections in the private sector. The cybersecurity standards for federal IoT devices and contractors are likely to both reflect and shift what security features are deemed “reasonable” — the legal standard adopted by California and Oregon for evaluating IoT device security.[36] The concept of reasonableness is also used to assert civil liability against product manufacturers by claiming that the lack of certain features or measures is unreasonable and a failure of the duty of care. As NIST is required to consider private sector best practices in developing its standards and guidelines, the public-private relationship can create a positive feedback loop that will propel IoT cybersecurity protections towards continuous improvement. Some manufacturers could maintain and highlight distinctions between public and private consumer security needs to attempt to avoid having the federal standards used against them in civil liability. Others manufacturers of IoT devices may simply find it easier to have uniform security mechanisms in both their government and private consumer products. Nonetheless, the developing standards and guidelines being established pursuant to the IoT Cybersecurity Improvement Act will have significant implications for the IoT device industry as a whole and should be carefully considered.

* * *

The legal issues and obligations related to the IoT Cybersecurity Improvement Act of 2020 are likely to shift as federal agencies implement its provisions. We will continue to monitor and advise on developments, and we are available to guide companies through these and related issues. Please do not hesitate to contact us with any questions.

______________________

[1] Cong. Rsch. Serv., H.R.1668 — IoT Cybersecurity Improvement Act of 2020: Summary, Congress.Gov, https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/1668 (last visited Dec. 29, 2020).

[2] Internet of Things Cybersecurity Improvement Act of 2020, Pub. L. No. 116-207, § 2(4), 134 Stat. 1001, 1001 (2020).

[4] U.S. Gov’t Accountability Off., GAO-20-577, Internet of Things: Information on Use by Federal Agencies 5 (2020).

[7] Shanhong Liu, Internet of Things in the U.S. — Statistics & Facts, Statista (May 29, 2020), https://www.statista.com/topics/5236/internet-of-things-iot-in-the-us.

[9] Patricia Moloney Figliola, Cong. Rsch. Serv., IF11239, The Internet of Things (IoT): An Overview 2 (2020), https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11239 (citing the predictions by IoT Analytics).

[11] IoT Cybersecurity Improvement Act § 4(a)(1).

[13] Id. § 4(b)(1)–(2). OMB shall conduct this review no later than 180 days after NIST completes the development of the relevant standards and guidelines. Id. § 4(b)(1).

[17] IoT Cybersecurity Improvement Act §§ 5(d)–(e), 6(a)–(c). OMB shall develop and oversee this implementation no later than two years after the Act is enacted. Id. § 6(a).

[23] NIST Special Publication 800-Series General Information, Nat’l Inst. Standards & Tech. (May 21, 2018), https://www.nist.gov/itl/publications-0/nist-special-publication-800-series-general-information.

[24] Michael Fagan et al., SP 800-213 (Draft) — IoT Device Cybersecurity Guidance for the Federal Government: Establishing IoT Device Cybersecurity Requirements, Nat’l Inst. Standards & Tech. (Dec. 2020), https://csrc.nist.gov/publications/detail/sp/800-213/draft.

[25] Defining IoT Cybersecurity Requirements: Draft Guidance for Federal Agencies and IoT Device Manufacturers (SP 800-213, NISTIRs 8259B/C/D), Nat’l Inst. Standards & Tech. (Dec. 15, 2020), https://www.nist.gov/news-events/news/2020/12/defining-iot-cybersecurity-requirements-draft-guidance-federal-agencies-and.

[26] Michael Fagan et al., NISTIR 8259 — Foundational Cybersecurity Activities for IoT Device Manufacturers, Nat’l Inst. Standards & Tech. (May 2020), https://csrc.nist.gov/publications/detail/nistir/8259/final; Michael Fagan et al., NISTIR 8259A — IoT Device Cybersecurity Capability Core Baseline, Nat’l Inst. Standards & Tech. (May 2020), https://csrc.nist.gov/publications/detail/nistir/8259a/final; Michael Fagan et al., NISTIR 8259B (Draft) — IoT Non-Technical Supporting Capability Core Baseline, Nat’l Inst. Standards & Tech. (Dec. 2020), https://csrc.nist.gov/publications/detail/nistir/8259b/draft; Michael Fagan et al., NISTIR 8259C (Draft) — Creating a Profile Using the IoT Core Baseline and Non-Technical Baseline, Nat’l Inst. Standards & Tech. (Dec. 2020), https://csrc.nist.gov/publications/detail/nistir/8259c/draft; Michael Fagan et al., NISTIR 8259D (Draft) — Profile Using the IoT Core Baseline and Non-Technical Baseline for the Federal Government, Nat’l Inst. Standards & Tech. (Dec. 2020), https://csrc.nist.gov/publications/detail/nistir/8259d/draft.

[27] Katerina Megas et al., NISTIR 8322 — Workshop Summary Report for “Building the Federal Profile For IoT Device Cybersecurity” Virtual Workshop, Nat’l Inst. Standards & Tech. (Jan. 2021), https://csrc.nist.gov/publications/detail/nistir/8322/final.

[28] See IoT Cybersecurity Improvement Act § 4(a)(1).

[30] See Nicole Perlroth, Hackers Used New Weapons to Disrupt Major Websites Across U.S., N.Y. Times (Oct. 21, 2016), https://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/22/business/internet-problems-attack.html.

[31] Nokia, Threat Intelligence Report 2020 9 (2020), https://onestore.nokia.com/asset/210088.

[32] See Cal. Civ. Code § 1798.91.04(a) (2018); Or. Rev. Stat. § 646A.813(2) (2019). Some states have proposed similar legislation. See, e.g., H.B. 3391, 101st Gen. Assemb., Reg. Sess. (Ill. 2019); A.B. 2229, Gen. Assemb., Reg. Sess. (N.Y. 2019); H.B. 888, 441st Gen. Assemb., Reg. Sess. (M.D. 2020).

[33] Sophia Antipolis, ETSI Releases World-Leading Consumer IoT Security Standard, ETSI (June 30, 2020), https://www.etsi.org/newsroom/press-releases/1789-2020-06-etsi-releases-world-leading-consumer-iot-security-standard.

[34] IoT Security: ENISA Publishes Guidelines on Securing the IoT Supply Chain, ENISA (Nov. 9, 2020), https://www.enisa.europa.eu/news/enisa-news/iot-security-enisa-publishes-guidelines-on-securing-the-iot-supply-chain.

[35] Dep’t for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport, Secure by Design, Gov.UK (July 16, 2020), https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/secure-by-design#history.

[36] See Cal. Civ. Code § 1798.91.04(a) (2018); Or. Rev. Stat. § 646A.813(2) (2019).

This article was prepared by Alexander H. Southwell and Terry Y. Wong.

Gibson Dunn’s lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding these developments. Please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, the authors, or any of the following members of the firm’s Privacy, Cybersecurity and Data Innovation practice group:

United States

Alexander H. Southwell – Co-Chair, PCDI Practice, New York (+1 212-351-3981, [email protected])

S. Ashlie Beringer – Co-Chair, PCDI Practice, Palo Alto (+1 650-849-5327, [email protected])

Debra Wong Yang – Los Angeles (+1 213-229-7472, [email protected])

Matthew Benjamin – New York (+1 212-351-4079, [email protected])

Ryan T. Bergsieker – Denver (+1 303-298-5774, [email protected])

Howard S. Hogan – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3640, [email protected])

Joshua A. Jessen – Orange County/Palo Alto (+1 949-451-4114/+1 650-849-5375, [email protected])

Kristin A. Linsley – San Francisco (+1 415-393-8395, [email protected])

H. Mark Lyon – Palo Alto (+1 650-849-5307, [email protected])

Karl G. Nelson – Dallas (+1 214-698-3203, [email protected])

Ashley Rogers – Dallas (+1 214-698-3316, [email protected])

Deborah L. Stein – Los Angeles (+1 213-229-7164, [email protected])

Eric D. Vandevelde – Los Angeles (+1 213-229-7186, [email protected])

Benjamin B. Wagner – Palo Alto (+1 650-849-5395, [email protected])

Michael Li-Ming Wong – San Francisco/Palo Alto (+1 415-393-8333/+1 650-849-5393, [email protected])

Cassandra L. Gaedt-Sheckter – Palo Alto (+1 650-849-5203, [email protected])

Europe

Ahmed Baladi – Co-Chair, PCDI Practice, Paris (+33 (0)1 56 43 13 00, [email protected])

James A. Cox – London (+44 (0) 20 7071 4250, [email protected])

Patrick Doris – London (+44 (0) 20 7071 4276, [email protected])

Kai Gesing – Munich (+49 89 189 33-180, [email protected])

Bernard Grinspan – Paris (+33 (0)1 56 43 13 00, [email protected])

Penny Madden – London (+44 (0) 20 7071 4226, [email protected])

Michael Walther – Munich (+49 89 189 33-180, [email protected])

Alejandro Guerrero – Brussels (+32 2 554 7218, [email protected])

Vera Lukic – Paris (+33 (0)1 56 43 13 00, [email protected])

Sarah Wazen – London (+44 (0) 20 7071 4203, [email protected])

Asia

Kelly Austin – Hong Kong (+852 2214 3788, [email protected])

Connell O’Neill – Hong Kong (+852 2214 3812, [email protected])

Jai S. Pathak – Singapore (+65 6507 3683, [email protected])

© 2021 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP

Attorney Advertising: The enclosed materials have been prepared for general informational purposes only and are not intended as legal advice.

London partners Michelle Kirschner and Matthew Nunan are the authors of “Reverse solicitation: a shot across the bow,” [PDF] first published by Thomson Reuters Regulatory Intelligence on February 10, 2021.

Notwithstanding the ongoing spread of COVID-19 and unprecedented changes in daily life and the economy, the second half of 2020 marched on to the steady drumbeat of securities-related lawsuits we have observed in recent years, including securities class and stockholder derivative actions, insider trading lawsuits, and government enforcement actions. In this 2020 year-end edition of our semi-annual publication, we discuss developments in the securities laws that have occurred against this backdrop.

The year-end update highlights what you most need to know in securities litigation developments and trends for the second half of 2020:

- Federal securities filings decreased by approximately 22% when compared to 2019, even as the average settlement value rose and the median settlement value remained comparable.

- The Supreme Court granted certiorari in Goldman Sachs Group Inc. v. Arkansas Teacher Retirement System, No. 20-222, and is set to review the Second Circuit’s inflation-maintenance theory and consider the use of price-impact evidence to rebut the presumption of reliance at the class certification stage.

- With the Supreme Court set to provide additional guidance on “price impact” theories under Halliburton II, the Seventh Circuit followed the Second Circuit’s path by requiring trial courts to consider evidence of a lack of price impact even where that evidence overlaps with a merits issue, such as materiality, and assigning both the burden of production and the burden of persuasion to defendants.

- The Delaware Supreme Court diminished Section 220’s threshold requirement that a stockholder have a “proper purpose” to inspect a corporation’s books and records, and may soon reduce or eliminate former stockholders’ standing to continue litigating “dual-natured” merger claims post-closing. We also discuss the fraud-on-the-board theory that survived a motion to dismiss in Mindbody.

- We continue to monitor courts’ application of the disseminator theory of liability recognized by the Supreme Court’s 2019 decision in Lorenzo.

- We again survey specific securities-related lawsuits arising in connection with or related to the coronavirus pandemic, including class actions, derivative actions, and government enforcement actions filed by both the Securities and Exchange Commission (the “SEC”) and the Department of Justice.

- We review developments regarding Omnicare’s falsity of opinions standard, as rulings by the Second Circuit and several district courts shed light on the boundaries of liability for false or misleading statements of opinion as well as omissions.

- Finally, we consider notable ERISA litigation activity, including how the Supreme Court’s early 2020 decisions in Sulyma and Jander have been applied by lower courts, as well as a potential circuit split regarding an employer’s fiduciary duties while offering a single-stock fund.

I. Filing And Settlement Trends

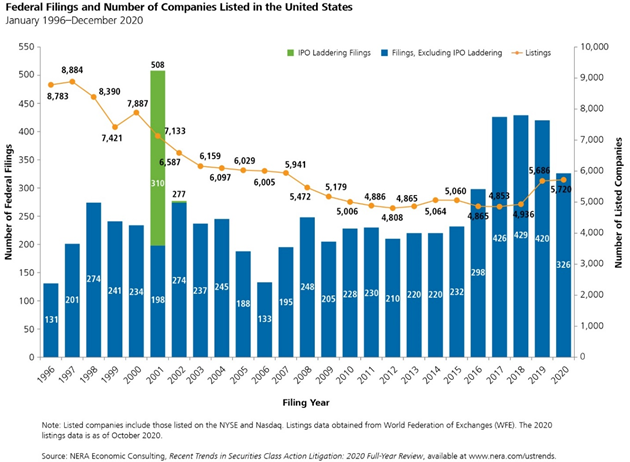

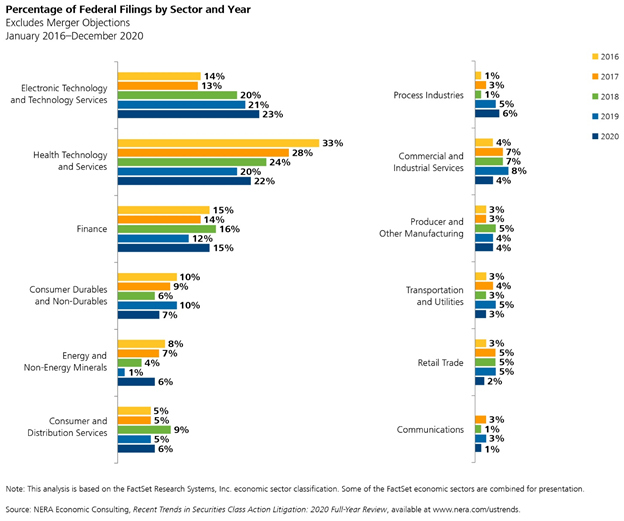

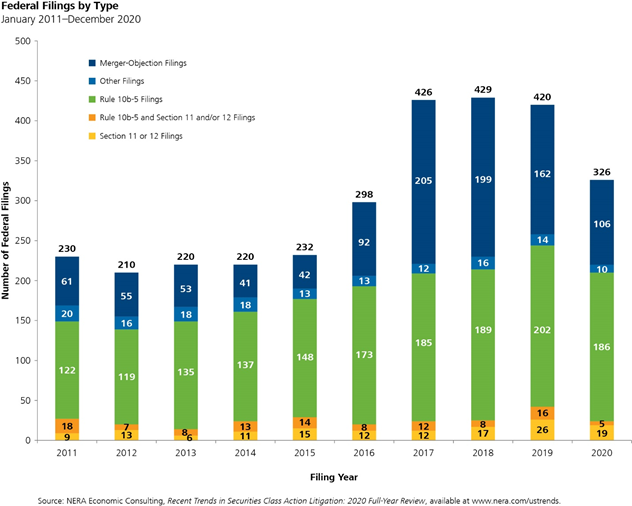

According to data from a newly released NERA Economic Consulting (“NERA”) study, filings and settlements in 2020 reflected the volatility of a tumultuous year, though certain aspects remained consistent with existing trends. For example, a decrease in the number of merger-objection cases filed in 2020 (down to 106 from 162 in 2019) drove a decline in the number of new federal class actions filed in 2020 (down to 326 from 420 in 2019). As in 2019, the most frequently litigated industry sectors continue to be the “Health Technology and Services” and “Electronic Technology and Technology Services” sectors, each rising by 2%.

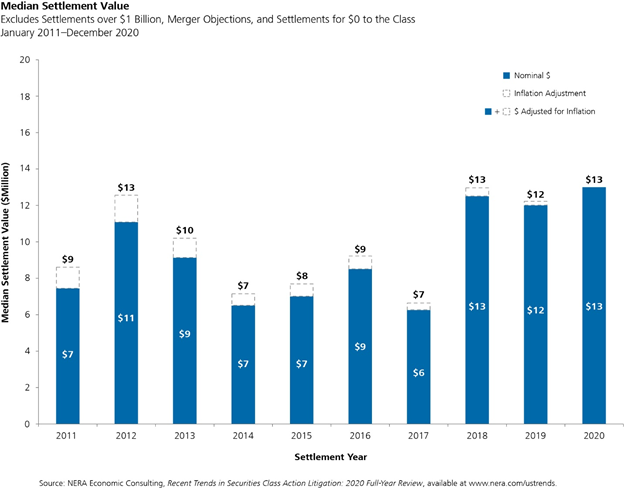

The median settlement value of federal securities cases in 2020—excluding merger-objection cases and cases settling for more than $1 billion or $0 to the class—was largely consistent with prior years (at $13 million, up from $12 million in 2019, and on par with $13 million in 2018). By contrast, average settlement values (excluding merger-objection and zero-dollar settlements) rose in 2020 (at $44 million, up from $29 million in 2019, though down from $73 million in 2018).

A. Filing Trends

Figure 1 below reflects filing rates for 2020 (all charts courtesy of NERA). 326 cases were filed last year, down considerably from the steady figures we have seen from 2017–2019. Note, however, that this figure does not include class action suits filed in state court or state court derivative suits, including those filed in the Delaware Court of Chancery.

Figure 1:

B. Mix Of Cases Filed In 2020

1. Filings By Industry Sector

As shown in Figure 2 below, the distribution of non-merger filings by industry was relatively consistent with 2019, even as the number of filings significantly decreased. The “Electronic Technology and Technology Services” and “Health Technology and Services” sectors continued to account for almost half of all filings, reaching 45% in 2020, with filings in both sectors rising by 2% over 2019. Notably, “Energy and Non-Energy Minerals” filings rose by 5% (at 6%, up from 1% in 2019), while “Commercial and Industrial Services” dropped by 4% (at 4%, down from 8% in 2019).

Figure 2:

2. Merger Cases

As shown in Figure 3 below, there were 106 merger-objection cases filed in federal court in 2020. This represents a 34.5% year-over-year decrease from 2019, and the lowest number of such filings since 2016, when the Delaware Court of Chancery put an effective end to the practice of disclosure-only settlements in In re Trulia Inc. Stockholder Litigation, 29 A.3d 884 (Del. Ch. 2016), which drove the increase in merger-objection filings between 2015 and 2017.

Figure 3:

C. Settlement Trends

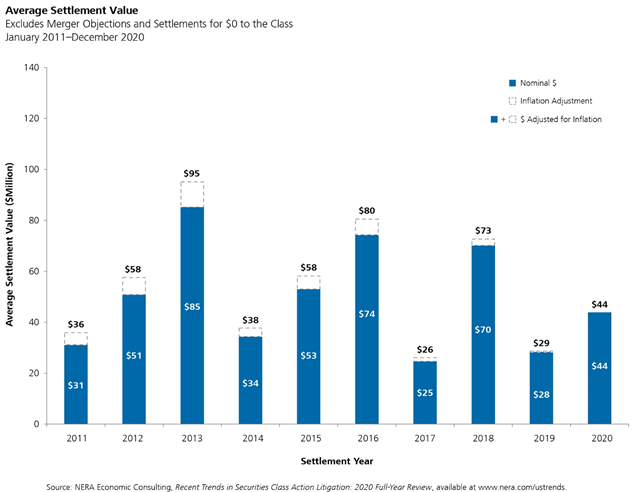

As reflected in Figure 4 below, the average settlement value rebounded in 2020, reaching $44 million, after declining by more than 50% from $73 million in 2018 to $29 million in 2019, although that decrease can primarily be attributed to the inclusion of a settlement in 2018 that exceeded $1 billion, which skewed the average.

Figure 4:

Turning to the median settlement value, and excluding settlements over $1 billion, we see in Figure 5 that the steady pace of 2018 ($13 million) and 2019 ($12 million) continued in 2020 ($13 million).

Figure 5:

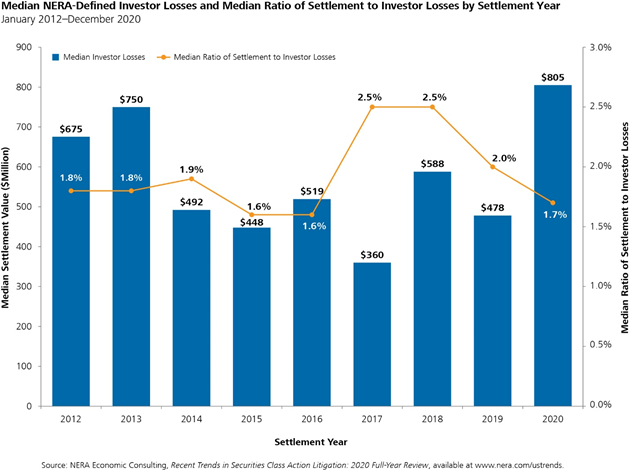

Finally, as shown in Figure 6, even though Median NERA-Defined Investor Losses rose steeply in 2020 to $805 million after a relatively consistent trend during the period 2014 through 2019, the Median Ratio of Settlement to Investor Losses fell for the second year in a row.

Figure 6:

II. What To Watch For In The Supreme Court

A. Supreme Court To Weigh In On Use Of Inflation Maintenance Theory

As we previewed in our 2020 Mid-Year Securities Litigation Update, the Supreme Court has granted certiorari in Goldman Sachs Group Inc. v. Arkansas Teacher Retirement System, No. 20-222, a case concerning the use of price-impact evidence to rebut the presumption of reliance at the class certification stage. ___ S. Ct. ___, 2020 WL 7296815 (Mem.) (Dec. 11, 2020). Recall that under Halliburton Co. v. Erica P. John Fund, Inc., 573 U.S. 258 (2014) (“Halliburton II”), the Supreme Court preserved the “fraud-on-the-market” presumption that enables courts to presume classwide reliance in Rule 10b-5 cases where plaintiffs satisfy certain prerequisites, but also opened the door to defendants rebutting that presumption at the class certification stage with evidence that the alleged misrepresentation did not impact the issuer’s stock price. Since then, lower courts have split on the viability of the “inflation maintenance” theory in this context. Arkansas Teacher Retirement System offers the Supreme Court the opportunity to resolve this split, squarely presenting the question of whether plaintiffs may use the inflation maintenance theory to demonstrate reliance by alleging that misstatements affected a stock price not by artificially inflating it, but by maintaining preexisting inflation.

By way of background, on April 7, 2020, a divided Second Circuit panel affirmed the trial court’s order certifying a class under the inflation maintenance theory premised on Goldman Sachs’s generic public statements. Arkansas Teacher Retirement System v. Goldman Sachs Group, Inc., 955 F.3d 254, 264–70 (2d Cir. 2020) (“Goldman Sachs II”). The plaintiffs did not make any showing that the challenged statements inflated the stock price, but rather premised their action on a drop in stock price following the announcement of a related regulatory action. Id. at 258–59, 262–63, 271, 273–74; see also id. at 275 (Sullivan, J., dissenting). In doing so, the Second Circuit rejected Goldman Sachs’s argument that the inflation maintenance theory may be applied only to “fraud-induced” inflation and should be narrowed to disallow its application to “general statements.” Id. at 265–70. The court also dismissed Goldman Sachs’s policy arguments that upholding inflation maintenance in these circumstances would “open the floodgates to unmeritorious litigation by allowing courts to certify classes that it believes should lose on the merits,” id. at 269, and that any time allegations of misconduct caused a stock to drop, “plaintiffs could just point to any general statement about the company’s business principles or risk controls and proclaim ‘price maintenance,’” id. (quoting Brief and Special Appendix for Defendants-Appellants at 52–53, Ark. Tchr. Ret. Sys. v. Goldman Sachs Grp., Inc., 955 F.3d 254 (2d Cir. 2020) (No. 18-3667), ECF No. 62).

Following the Second Circuit’s denial of rehearing en banc in June 2020 in Goldman Sachs II, Order, Ark. Tchr. Ret. Sys. v. Goldman Sachs Grp., Inc., No. 18-3667 (2d Cir. June 15, 2020), ECF No. 277, it was expected that the Supreme Court would consider this important issue. On December 11, 2020, after reviewing amicus briefs from the Society for Corporate Governance, former SEC officials and law professors, and financial economists, the Supreme Court granted the defendants’ petition for a writ of certiorari.

The Supreme Court will consider (1) whether the defendant in a securities class action may rebut the presumption of classwide reliance recognized in Basic Inc. v. Levinson, 485 U.S. 224 (1988), by pointing to the generic nature of the alleged misstatements in showing that the statements had no impact on the price of the security, even though that evidence is also relevant to the substantive element of materiality, and (2) whether a defendant seeking to rebut the Basic presumption has only a burden of production or also the ultimate burden of persuasion. Petition for Writ of Certiorari at I, Goldman Sachs (No. 20-222).

If the Supreme Court rejects the Second Circuit’s inflation-maintenance theory, it would protect the foundational importance of price impact to the Basic presumption of reliance, and would enable securities class action defendants to defeat the Basic presumption using any price-impact evidence—direct as well as indirect—even if that evidence overlaps with a later merits inquiry. It would stop plaintiffs from establishing price impact by pointing only to a company’s generic, aspirational statements and a subsequent stock drop in response to some enforcement activity. It would also preclude plaintiffs from showing loss causation by merely alleging that investors purchased stock at inflated prices and later suffered losses. On the other hand, if the Court were to affirm the Second Circuit’s approach, we expect a proliferation of “inflation maintenance” class actions based on a company’s general statements.

B. Questions Over Constitutional Challenges To Power Or Appointment Of Administrative Adjudicators

Readers will recall the Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Lucia v. SEC, 138 S. Ct. 2044, 2053 (2018), as discussed in our 2018 Mid-Year Securities Enforcement Update, that administrative law judges (“ALJs”) are “Officers” under the Appointments Clause and therefore must be appointed by either the President, the SEC, or a court of law. The Supreme Court’s holding in Lucia continues to generate constitutional questions over the appointment of administrative adjudicators, which could have implications for anyone considering bringing similar challenges against an ALJ of the SEC.

On March 1, 2021, the Supreme Court is set to hear argument in United States v. Arthrex, No. 19-1434 et al., which presents the question whether administrative adjudicators in the Patent and Trademark Office are “principal” or “inferior” Officers of the United States for purposes of the Appointments Clause. These consolidated cases present a question, not resolved by Lucia, as to how to categorize administrative adjudicators in light of their functions, supervision, and (possibly) removal protections. Gibson Dunn represents Smith & Nephew and ArthroCare Corp., the petitioners in No. 19-1452, in arguing (alongside the government) that administrative patent judges (“APJs”) are inferior Officers and were therefore permissibly appointed by the Secretary of Commerce. The Court’s resolution of the categorization issue in the context of APJs could have impacts for administrative adjudicators in other agencies.

On March 3, 2021, the Supreme Court is set to hear argument in Carr v. Saul and Davis v. Saul, a pair of consolidated cases involving whether parties need to present constitutional challenges to the appointment of administrative adjudicators at their administrative hearing in order to preserve the challenge for their later appeal. In both Carr and Davis, the petitioners filed for disability benefits under the Social Security Act, only for their claims to be denied by the Social Security Administration (“SSA”), the administrative tribunal, and the agency’s appeals board. Carr v. Comm’r, 961 F.3d 1267, 1268 (10th Cir. 2020); Davis v. Saul, 963 F.3d 790, 791 (8th Cir. 2020). Petitioners sought review in federal district court, and in light of Lucia, for the first time challenged the constitutionality of the appointment of the SSA ALJs. In Carr, the district court reversed the SSA decisions and remanded for new hearings before constitutionally appointed ALJs, while in Davis, the district court found that the petitioners had waived those challenges by not first bringing them during the administrative proceedings themselves. 961 F.3d at 1270; 963 F.3d at 792–93. On appeal, both the Eighth and Tenth Circuit Courts of Appeals agreed that the challenges had been waived by not being brought directly before the SSA. 961 F.3d at 1276; 963 F.3d at 795. The Court’s decision in these consolidated cases should help clarify the applicability of preservation, waiver, and forfeiture principles to these type of structural challenges.

III. Delaware Development

A. Recent Trends In Section 220 Litigation

Since the Delaware Supreme Court’s decision in Corwin v. KKR Financial Holdings LLC, 125 A.3d 304 (Del. 2015), stockholder plaintiffs have increasingly sought company books and records under Section 220 of the Delaware General Corporation Law to aid in drafting complaints that can withstand dismissal. See, e.g., Morrison v. Berry, 191 A.3d 268, 273, 275 (Del. 2018) (reversing dismissal under Corwin by relying on “crucial” documents obtained pursuant to Section 220). This uptick in Section 220 demands is not surprising, as Corwin established a formidable hurdle to plaintiffs hoping to overcome a motion to dismiss, as discussed in our 2017 Mid-Year Securities Litigation Update. Further, Delaware courts have “repeatedly admonished plaintiffs to use the ‘tools at hand’ and to request company books and records under Section 220 to attempt to substantiate their allegations before filing derivative complaints.” California State Teachers’ Ret. Sys. v. Alvarez, 179 A.3d 824, 839 (Del. 2018) (citation omitted).

1. Delaware Supreme Court Tosses “Proper Purpose” Requirement Except In “Rare” Circumstances

Section 220 permits a stockholder to inspect the company’s books and records for any “proper purpose” reasonably related to the stockholder’s “interest as a stockholder.” 8 Del. C. § 220(b). One well-recognized “proper purpose” that stockholders commonly assert is investigating alleged corporate mismanagement or wrongdoing, but a stockholder’s curiosity alone will not permit such an investigation. Seinfeld v. Verizon Commc’ns, Inc., 909 A.2d 117, 121–22 (Del. 2006). Instead, the stockholder must demonstrate “a credible basis from which the court can infer that mismanagement, waste or wrongdoing may have occurred.” Lavin v. West Corp., 2017 WL 6728702, at *7 (Del. Ch. Dec. 29, 2017) (quoting Seinfeld, 909 A.2d at 118). Although the “credible basis” standard imposes “the lowest possible burden of proof” under Delaware law, see Seinfeld, 909 A.2d at 123, Delaware case law has required stockholders to present some evidence to demonstrate that the alleged wrongdoing could be actionable, see United Techs. Corp. v. Treppel, 109 A.3d 553, 559 & n.31 (Del. 2014), and identify the course of action the stockholder plans to pursue if its demand succeeds, see Sec. First Corp. v. U.S. Die Casting & Dev. Co., 687 A.2d 563, 570 (Del. 1997).

Recently, however, the Delaware Supreme Court held in AmerisourceBergen Corp. v. Lebanon County Employees’ Retirement Fund, “that a stockholder is not required to state the objectives of his investigation” to satisfy Section 220’s “proper purpose” requirement. 2020 WL 7266362, at *6 (Del. Dec. 10, 2020). The Court reasoned that so long as the stockholder states a credible basis to support an inference of mismanagement or wrongdoing, the stockholder need not “specify the ends to which it might use the books and records” should they confirm suspicions of mismanagement or wrongdoing. Id. at *7. The Court also held that, except in “rare” circumstances, a stockholder “need not demonstrate that the alleged mismanagement or wrongdoing is actionable” to obtain company books and records under Section 220. Id. at *13–14.

In light of the developing case law in the Section 220 context, companies should continue to “honor traditional corporate formalities” in acting and maintaining corporate communications and record-keeping regarding its actions. See KT4 Partners LLC v. Palantir Techs. Inc., 203 A.3d 738, 742, 758 (Del. 2019) (ordering directors to produce emails in response to a Section 220 request, where the company “did not honor traditional corporate formalities . . . and had acted through email in connection with the same alleged wrongdoing that [the stockholder] was seeking to investigate”).

2. Delaware Corporations Not Subject To California Inspection Statute

In another recent decision concerning the inspection rights of stockholders, the Delaware Court of Chancery held that Delaware law precluded a stockholder of a Delaware corporation headquartered in California from seeking books and records under California’s inspection statute, California Corporations Code Section 1601. JUUL Labs, Inc. v. Grove, 238 A.3d 904, 913–18 (Del. Ch. 2020). The court explained that Delaware law governs the internal affairs of Delaware corporations and “[s]tockholder inspection rights are a core matter of internal corporate affairs.” Id. at 915. The court highlighted that the internal affairs doctrine serves “an important public policy . . . to ensure the uniform treatment of directors, officers, and stockholders across jurisdictions,” which the court noted “can only be attained by having the rights and liabilities of those persons with respect to the corporation governed by a single law.” Id. (citation and internal quotation marks omitted). Accordingly, the court held that the stockholder could not seek inspection under Section 1601. Id. at 918. This decision should help Delaware-incorporated companies limit the burden associated with responding to conflicting, burdensome, and invasive books and records demands under the laws of states other than Delaware.

B. Delaware Supreme Court May Eliminate Standing To Litigate “Dual-Natured” Merger Claims Post-Closing

Despite declining the opportunity to reject precedent that permits stockholders to litigate “dual-natured” merger claims post-closing, the Court of Chancery recently invited the Delaware Supreme Court to do so by certifying its decision in In re TerraForm Power, Inc. Stockholders Litigation, 2020 WL 6375859 (Del. Ch. Oct. 30, 2020), for interlocutory appeal. In TerraForm Power, Inc., plaintiff stockholders asserted breach of fiduciary duty claims against several directors, the CEO, and the majority stockholder of TerraForm Power, Inc., alleging that the controlling stockholder caused TerraForm “to issue [the controlling stockholder] stock for inadequate value, diluting both the financial and voting interest of the minority stockholders.” 2020 WL 6375859, at *1, *2. Defendants moved to dismiss for lack of standing, arguing that such dilution claims are “quintessential derivative claims that belong to the corporation” and could not be asserted by plaintiffs, who had ceased to be stockholders at the time of the motion due to a merger. Id. at *1. But Vice Chancellor Glasscock found that the facts alleged in TerraForm Power, Inc. were “indistinguishable” from those at issue in Gentile v. Rossette, 906 A.2d 91 (Del. 2006). TerraForm Power, Inc., 2020 WL 6375859, at *11. In Gentile, the Delaware Supreme Court held that, where a controlling stockholder dilutes the “economic value and voting power” of a minority stockholder’s shares by “caus[ing] the corporation” to issue itself shares for inadequate compensation, the minority stockholder is not deprived of standing to prosecute such claims after the merger closes because they are in the nature of both direct and derivative claims. Gentile, 906 A.2d at 100. Accordingly, Vice Chancellor Glasscock explained that he was bound by Delaware Supreme Court precedent and, as such, Gentile “mandate[d] that the direct claims pled survive” the motion to dismiss. TerraForm Power, Inc., 2020 WL 6375859, at *16.

In light of the criticism surrounding Gentile, however, Vice Chancellor Glasscock certified an interlocutory appeal of his decision to the Delaware Supreme Court to address whether Gentile remains good law. In re TerraForm Power, Inc. S’holders Litig., 2020 WL 6889189 (Del. Ch. Nov. 24, 2020). We will monitor the progress of this appeal and report on any developments in future editions of our Securities Litigation Update.