The False Claims Act (FCA) is well-known as one of the most powerful tools in the government’s arsenal to combat fraud, waste and abuse anywhere government funds are implicated. The U.S. Department of Justice has issued statements and guidance under the Trump Administration that has effectuated changes in DOJ’s approach to FCA cases. But at the same time, newly filed FCA cases remain at historical peak levels and the DOJ has enjoyed ten straight years of nearly $3 billion or more in annual FCA recoveries. The government has also made clear that it intends vigorously to pursue any fraud, waste and abuse in connection with COVID-related stimulus funds. As much as ever, any company that deals in government funds—especially in the government contracting sector—needs to stay abreast of how the government and private whistleblowers alike are wielding this tool, and how they can prepare and defend themselves.

Please join us to discuss developments in the FCA, including:

- The latest trends in FCA enforcement actions and associated litigation affecting government contractors;

- Updates on the Trump Administration’s approach to FCA enforcement, including developments with recent DOJ Civil Division personnel changes and DOJ’s use of its statutory dismissal authority;

- The coming surge of COVID-related FCA enforcement actions; and

- The latest developments in FCA case law, including developments in particular FCA legal theories affecting your industry and the continued evolution of how lower courts are interpreting the Supreme Court’s Escobar decision.

View Slides (PDF)

PANELISTS:

Jonathan M. Phillips is a partner in the Washington, D.C. office where he focuses on compliance, enforcement, and litigation in the health care and government contracting fields, as well as other white collar enforcement matters and related litigation. A former Trial Attorney in DOJ’s Civil Fraud section, he has particular experience representing clients in enforcement actions by the DOJ, Department of Health and Human Services, and Department of Defense brought under the False Claims Act and related statutes.

Erin N. Rankin is an associate in the Washington, D.C. office. She has extensive experience litigating government contract disputes and advising clients on FAR and DFARS compliance, with a particular focus on cost and pricing issues. Ms. Rankin also assists clients with all types of legal questions and disputes that arise in the creation, performance, and closing out of government contracts. She defends clients against False Claims Act allegations, negotiates and drafts subcontracts, conducts internal investigations, navigates disputes between prime and subcontractors, and represents clients in mandatory disclosures and suspension and debarment proceedings.

Andrew Tulumello is a partner in the Washington, D.C. office. He has represented several government contractors in investigations, suits, and trials (both by qui tam relators and the Department of Justice) under the False Claims Act involving federal contracts worth billions of dollars, including representing a leading defense contractor in 10(b) and derivative litigation following a $500 million deferred prosecution agreement with the Department of Justice. He was profiled by The National Law Journal in recognizing Gibson Dunn’s Washington. D.C. office as the Litigation Department of the Year, in The National Law Journal’s 2017 Appellate Hot List, and by Bloomberg BNA (“Deflategate Lawyer Heads to High Court in Securities Case”).

James Zelenay is a partner in the Los Angeles office where he practices in the firm’s Litigation Department. He is experienced in defending clients involved in white collar investigations, assisting clients in responding to government subpoenas, and in government civil fraud litigation. He also has substantial experience with the federal and state False Claims Acts and whistleblower litigation, in which he has represented a breadth of industries and clients, and has written extensively on the False Claims Act.

On September 25, 2020, California Governor Gavin Newsom signed into law the California Consumer Financial Protection Law (CCFPL), which was passed by the state legislature on August 31, 2020.[1] Under the CCFPL, California’s Department of Business Oversight (DBO) has been renamed the Department of Financial Protection and Innovation (DFPI). Modeled after the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) provisions in the Dodd-Frank Act, the CCFPL aims to strengthen consumer protections by expanding the regulatory authority of the DFPI and promoting access to responsible and affordable credit. The substantive provisions of the CCFPL go into effect on January 1, 2021.

The effects of the CCFPL will be felt most immediately by certain nonbank financial companies – for example, payday lenders and student loan servicers – as well as affiliated “service providers” to financial companies, because of statutory exclusions for regulated banks and many other current DBO nonbank licensees. This said, the CCFPL also gives the DFPI the authority to define other financial services whose providers would thereby become subject to its jurisdiction, and it includes new provisions relating to unfair, deceptive and abusive acts and practices enforcement authority (UDAAP) over statutorily covered persons and service providers. The DFPI will also have the authority to bring civil actions under the Dodd-Frank Act’s consumer protection provisions against all state-licensed banks and nonbank financial companies. As a result, financial institutions doing business in California are now facing a potentially powerful and reinvigorated regulatory authority.

I. Jurisdiction

The CCFPL grants authority to the DFPI to regulate the offering and provision of consumer financial products or services under California’s consumer financial laws, to exercise nonexclusive oversight and enforcement authority under California’s consumer financial laws, and, to the extent permissible under federal consumer financial laws, nonexclusive oversight and enforcement under federal consumer financial laws as well.[2]

The CCFPL’s definition of “consumer financial products and services” closely parallels the broad definition in Title X of the Dodd-Frank Act and its implementing regulations;[3] these include any financial product or service that is delivered, offered, or provided for use by consumers primarily for personal, family, or household purposes.[4] The definition also includes brokering the offer or sale of a franchise in California on behalf of another.[5] Similar to the authority granted to the CFPB under the Dodd-Frank Act, the DFPI will have authority to issue regulations defining any other financial product or service when the financial product or service (i) is entered into or conducted as a subterfuge or with a purpose to evade consumer financial law or (ii) will likely have a material impact on consumers, in each case, subject to certain exceptions.[6]

As a general matter, the CCFPL applies to “covered persons.” Subject to the important exclusions discussed immediately below, this includes (1) any person that engages in offering or providing a consumer financial product or service to a resident of California, (2) any affiliate of a covered person that acts as a service provider, and (3) any service provider to the extent that person offers or provides its own consumer financial product or service.[7] A “service provider” is any person that provides a material service to a covered person in connection with the covered person’s offering or provision of a consumer financial product or service.[8]

Reflecting a legislative compromise, the CCFPL does not apply to the following entities that were previously subject to licensing and DBO regulation: banks, bank holding companies, trust companies, savings and loan associations, savings and loan holding companies, credit unions, industrial loan corporations, insurers, certain electronic financial data transmitters, escrow agents, finance lenders and brokers, mortgage loan originators, broker-dealers, investment advisers, residential mortgage lenders, mortgage servicers, and money transmitters.[9] Payday lenders and student loan servicers, however, are not excluded. Also excluded are licensees of other state agencies and their employees where the licensee or employee is acting under the authority of the other state agency’s license (for example, real estate brokers).[10]

II. UDAAP

Like Title X of Dodd-Frank, the CCFPL contains expanded UDAAP (unfair, deceptive or abusive acts and practices) authority over “covered persons” and “service providers.” The CCFPL permits the DFPI to take action against a covered person or service provider that engages, has engaged, or proposes to engage in UDAAPs with respect to consumer financial products or services.[11] In addition to enforcement authority, the CCFPL authorizes the DFPI to prescribe rules applicable to any covered person or service provider regarding UDAAP, subject to the following limitations.[12] The DFPI must interpret “unfair” and “deceptive” in a manner consistent with California’s broad Unfair Competition Law and case law thereunder.[13] In this area, the definition of “unfair” remains unsettled.[14] Courts typically use one of two tests to determine “unfairness”: (1) an “examination of [the practice’s] impact on its alleged victim, balanced against the reasons, justifications and motives of the alleged wrongdoer”[15] or (2) the Federal Trade Commission’s definition of “unfair” conduct.[16] As for the term “abusive,” the CCFPL requires that it must be interpreted consistently with Title X of the Dodd-Frank Act, and any inconsistency must be resolved in favor of greater protections to the consumer and more expansive coverage.[17]

In addition to UDAAP authority, the DFPI is authorized to bring civil actions or other appropriate proceedings to enforce the consumer protection provisions of Title X of the Dodd-Frank Act and the CFPB’s regulations thereunder, with respect to any entity licensed, registered or subject to DFPI oversight.[18]

III. Other Enforcement Powers

In addition to its UDAAP authority, the DFPI may enforce consumer financial laws with respect to covered persons, service providers, and – broadening its authority substantially – persons who knowingly or recklessly provide substantial assistance to a covered person or service provider in violating consumer financial law.[19] This authority applies only to acts or practices engaged in on or after the January 1, 2021.[20]

The DFPI also has the power to bring administrative and civil actions, issue subpoenas, hold hearings, issue publications, and conduct investigations.[21] It may issue orders directing a person to desist and refrain from engaging in an activity, act, practice or course of business; such injunctive orders become effective and final if a respondent does not request a hearing within 30 days.[22] After notice and an opportunity for a hearing, the DFPI can suspend or revoke the license or registration of a covered person or service provider.[23] The DFPI can also apply to the appropriate superior court for an order compelling the cited licensee or person to comply with its orders.[24]

No civil action can be brought by the DFPI more than four years after the date of discovery of the violation to which an action relates.[25] What constitutes the “date of discovery” is undefined in the CCFPL and similarly undefined in Title X of the Dodd-Frank Act. The United States District Court for the Northern District of California, however, has held that the CFPB’s limitations period begins running when the CFPB “actually” discovers facts constituting a violation or when a “reasonably diligent plaintiff would have” discovered those facts.[26] If, however, an action arises solely under a California or federal consumer financial law, the limitations period under such consumer financial law will apply.[27]

With respect to UDAAP violations, the DFPI will have at its disposal the same wide-ranging remedial tools as the CFPB, including rescission or reformation of contracts, refund of moneys or return of real property, restitution, disgorgement or compensation for unjust enrichment, payment of damages, public notification regarding the violation, and limits on the activities or functions of the violator.[28] Like Title X of the Dodd-Frank Act, the CCFPL does not authorize exemplary or punitive damages,[29] but does empower the DFPI to impose considerable penalties for violations.[30]

|

CCFPL Penalties | ||||

|

May not exceed the greater of | ||||

| Violation | $5,000 for each day the violation continues | $2,500 for each act or omission in violation | ||

| Reckless Violation | $25,000 for each day the violation continues | $10,000 for each act or omission in violation | ||

|

May not exceed the lesser of | ||||

| Knowing Violation | $1,000,000 for each day the violation continues | $25,000 for each act or omission in violation | 1% of the violator’s total assets | |

IV. Consumer Complaints

The CCFPL authorizes the DFPI to promulgate regulations to round out its investigatory authority. Like the CFPB, the DFPI may promulgate rules and procedures governing informational requests from covered persons concerning consumer complaints or inquiries.[31] The DFPI is required to finalize its complaint response procedures before it may commence an enforcement action against a covered person or service provider for a violation of these provisions.[32] The DFPI may, however, make the information requests themselves beginning on January 1, 2021. Notably, these provisions do not apply to consumer complaints regarding credit reporting agencies.

V. Registration

Covered persons engaged in the business of offering or providing a consumer financial product or service may become subject to new registration requirements and attendant fees, as the latter will help support the DFPI’s operating budget.[33] The authority to promulgate rules related to the registration and reporting of covered persons will expand the reach of the DFPI to oversee entities that are not currently subject to licensure or registration. In order to deter regulation by enforcement, the CCFPL requires the DFPI to promulgate registration rules no later than three years following the initiation of its second action to enforce a violation of the CCFPL by persons providing the same or substantially similar consumer financial product or service.[34]

VI. Covered Person Reporting

Like the CFPB, the DFPI can require a covered person to generate, provide, or retain records for the purposes of facilitating oversight and assessing and detecting risks to consumers.[35] In conducting any monitoring, regulatory or assessment activity, the DFPI can also gather information regarding the organization, business conduct, markets, and activities of any covered persons or service providers.[36]

VII. DFPI Reporting

The DFPI must prepare and publish an online annual report detailing actions taken during the prior year.[37] The report must include information on actions with respect to rulemaking, enforcement, oversight, consumer complaints and resolutions, education, research, and the activities of the Financial Technology Innovation Office.[38] The report may also include recommendations, including those intended to result in improved oversight, greater transparency, or increased availability of beneficial financial products and services in the marketplace.[39]

VIII. Conclusion

Notwithstanding its exclusions for many entities previously subject to DBO oversight, the CCFPL creates a more powerful state financial services regulator with new registration authority, expanded enforcement authority, and UDAAP authority. If it makes full use of the CCFPL’s powers, the DFPI will become a significant consumer regulator. Firms that offer consumer financial products and services in California will therefore need to pay close attention to the DFPI in 2021 as it begins to implement its new statutory authority.

______________________

[1] California Assembly Bill 1864 (passed August 31, 2020), available here.

[3] See 12 C.F.R. § 1091.101 (definition of “consumer financial product or service”) and 12 U.S.C. § 5481(15) (definition of “financial product or service”).

[4] New Cal. Fin. Code § 90005(c).

[5] Id. § 90005(e). For a complete list of “financial products or services,” see id. § 90005(k).

[6] Compare New Cal. Fin. Code § 90005(k)(12) with 12 U.S.C. § 5481(15)(A)(xi).

[7] New Cal. Fin. Code § 90005(f).

[11] Id. §§ 90012(a); 90009(c); 12 U.S.C. § 5531(a), (b).

[12] New Cal. Fin. Code § 90009(c). The statute further authorizes the DFPI to define UDAAP in connection with the offering or provision of commercial financing or other financial products and services to small business recipients, nonprofits, and family farms. Id. § 90009(c)(3).

[14] See, e.g., Mui Ho v. Toyota Motor Corp., 931 F. Supp. 2d 987, 1000 n.5 (N.D. Cal. 2013) (“California courts and the legislature have not specified which of several possible ‘unfairness’ standards is the proper one.”); Ferrington v. McAfee, Inc., No. 10-CV-01455-LHK, 2010 WL 3910169, at *11 (N.D. Cal. Oct. 5, 2010) (“California law is currently unsettled with regard to the correct standard to apply to consumer suits alleging claims under the unfair prong of the UCL.”).

[15] Motors, Inc. v. Times Mirror Co., 102 Cal. App. 3d 735, 740 (1980).

[16] The Federal Trade Commission Act provides that an act or practice is unfair when (1) it causes or is likely to cause substantial injury to consumers, (2) the injury is not reasonably avoidable by consumers and (3) the injury is not outweighed by countervailing benefits to consumers or to competition. 15 U.S.C. § 45(n). The CFPB uses the same standard for unfairness. 12 U.S.C. § 5531(c).

[17] New Cal. Fin. Code § 90009(c)(3).

[26] See Consumer Financial Protection Bureau v. Nationwide Biweekly Administration, Inc., et. al., No. 15-cv-02106-RS (N.D. Cal. Sep. 8, 2017)

[27] New Cal. Fin. Code § 90014.

[29] Compare New Cal. Fin. Code § 90013(d) with 12 U.S.C. § 5565(a)(3).

[30] New Cal. Fin. Code § 90013(d).

[31] Id. § 90008. Notably, these provisions do not apply to consumer complaints regarding consumer reporting agencies. Id.

[35] Id. § 90009(b); 12 U.S.C. § 5514(b)(7)(B).

[36] New Cal. Fin. Code § 90010(f).

The following Gibson Dunn lawyers assisted in preparing this client update: Arthur S. Long, Benjamin B. Wagner, James O. Springer and Samantha J. Ostrom.

Gibson Dunn’s lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding these developments. Please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work in the firm’s Financial Institutions practice group, or the following:

Arthur S. Long – New York (+1 212-351-2426, [email protected])

Matthew L. Biben – New York (+1 212-351-6300, [email protected])

Michael D. Bopp – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-955-8256, [email protected])

Stephanie Brooker – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3502, [email protected])

M. Kendall Day – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-955-8220, [email protected])

Mylan L. Denerstein – New York (+1 212-351- 3850, [email protected])

Jeffrey L. Steiner – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3632, [email protected])

Benjamin B. Wagner – Palo Alto (+1 650-849-5395, [email protected])

James O. Springer – New York (+1 202-887-3516, [email protected])

Samantha J. Ostrom – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-955-8249, [email protected])

© 2020 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP

Attorney Advertising: The enclosed materials have been prepared for general informational purposes only and are not intended as legal advice.

New York of counsel Karin Portlock and associate Vinay Limbachia are the authors of “The Constitutional Risks In Pandemic-Era Criminal Jury Trials” published by Law360 on October 9, 2020.

Washington, D.C. partner Judith Alison Lee, of counsel Christopher Timura, and associates R.L. Pratt and Scott Toussaint are the authors of “U.S. Export Controls: The Future of Disruptive Technologies” [PDF] published in the NATO Legal Gazette, Issue 41 in October 2020.

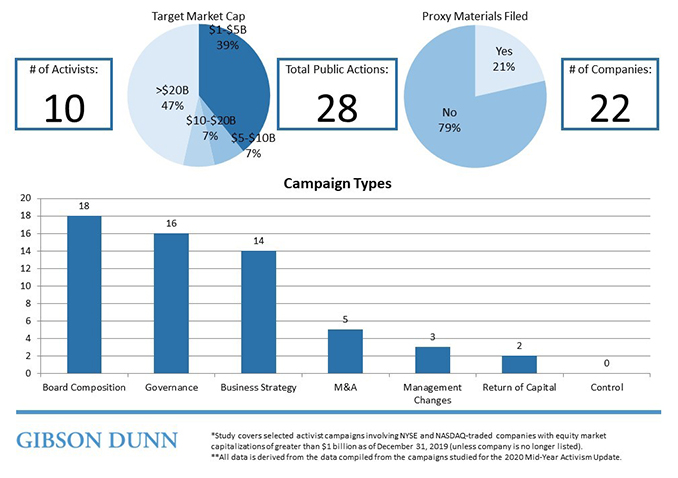

This Client Alert provides an update on shareholder activism activity involving NYSE- and Nasdaq-listed companies with equity market capitalizations in excess of $1 billion and below $100 billion (as of the close of trading on June 30, 2020) during the first half of 2020. As the markets weathered the dislocation caused by the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, shareholder activist activity decreased dramatically. Relative to the first half of 2019, the number of public activist actions declined from 51 to 28, the number of activist investors taking actions declined from 33 to 10 and the number of companies targeted by such actions declined from 46 to 22.

By the Numbers – H1 2020 Public Activism Trends

Additional statistical analyses may be found in the complete Activism Update linked below.

The decline in shareholder activism activity brought concentration among those investors engaged in activist activity during the first half of 2020. For example, during the first half of 2020, NorthStar Asset Management launched six campaigns and Starboard Value LP launched four campaigns. Three activists represented half of the total public activist actions that began during the first half of 2020.

In addition, as compared to the first half of 2019, activists turned their focus away from agitating for particular transactions as the animating rationale for the campaigns they launched. While changes in board composition remained the leading rationale for campaigns initiated in the first half of 2019 and the first half of 2020, M&A (which includes advocacy for or against spin-offs, acquisitions and sales) and acquisitions of control, which served as the rationale for 24% and 8%, respectively, of activist campaigns in the first half of 2019, declined to 9% and 0%, respectively, in the first half of 2020. By contrast, advocacy for changes in governance, which emerged in 6% of campaigns in the first half of 2019, became the principal rationale for 28% of campaigns in the first half of 2020. Business strategy also remained a high-priority area of focus for shareholder activists, representing the rationale for 22% of campaigns begun in the first half of 2019 and 24% of campaigns begun in the first half of 2020. The rate at which activists engaged in proxy solicitation remained consistent at 24% in the first half of 2019 and 21% in the first half of 2020. (Note that the percentages for campaign rationales described in this paragraph sum to over 100%, as certain activist campaigns had multiple rationales.)

Publicly filed settlement agreements declined alongside the decrease in shareholder activism activity. Nine settlement agreements were filed during the first half of 2020, as compared to 17 such agreements during the first half of 2019. Nonetheless, the settlement agreements into which activists and companies entered contained many of the same features noted in prior reviews, including voting agreements and standstill periods as well as non-disparagement covenants and minimum and/or maximum share ownership covenants. Expense reimbursement provisions appeared in two thirds of the settlement agreements reviewed, which represented an increase relative to historical trends. We delve further into the data and the details in the latter half of this Client Alert.

We hope you find Gibson Dunn’s 2020 Mid-Year Activism Update informative. If you have any questions, please do not hesitate to reach out to a member of your Gibson Dunn team.

Gibson Dunn’s lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding the issues discussed in this publication. For further information, please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, or any of the following authors in the firm’s New York office:

Barbara L. Becker (+1 212.351.4062, [email protected])

Dennis J. Friedman (+1 212.351.3900, [email protected])

Richard J. Birns (+1 212.351.4032, [email protected])

Eduardo Gallardo (+1 212.351.3847, [email protected])

Saee Muzumdar (+1 212.351.3966, [email protected])

Daniel S. Alterbaum (+1 212.351.4084, [email protected])

Jessica L. Bondy (+1 212.351.3802, [email protected])

Please also feel free to contact any of the following practice group leaders and members:

Mergers and Acquisitions Group:

Jeffrey A. Chapman – Dallas (+1 214.698.3120, [email protected])

Stephen I. Glover – Washington, D.C. (+1 202.955.8593, [email protected])

Jonathan K. Layne – Los Angeles (+1 310.552.8641, [email protected])

Securities Regulation and Corporate Governance Group:

Brian J. Lane – Washington, D.C. (+1 202.887.3646, [email protected])

Ronald O. Mueller – Washington, D.C. (+1 202.955.8671, [email protected])

James J. Moloney – Orange County, CA (+1 949.451.4343, [email protected])

Elizabeth Ising – Washington, D.C. (+1 202.955.8287, [email protected])

Lori Zyskowski – New York (+1 212.351.2309, [email protected])

© 2020 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP

Attorney Advertising: The enclosed materials have been prepared for general informational purposes only and are not intended as legal advice.

California’s housing shortage continues as the state grapples with the COVID-19 pandemic. In an effort to mitigate delays in housing production throughout the state, California Governor Gavin Newsom recently signed into law Assembly Bill 1561 (“AB 1561”), which extends the validity of certain categories of residential development entitlements. Devised as a remedy for impediments to housing development as a result of interruptions in planning, financing, and construction due to the pandemic, AB 1561 helps cities and counties that would otherwise need to devote significant resources to addressing individual permit extensions on a case-by-case basis.

AB 1561 adds a new section to the state’s Government Code, Section 65914.5, that extends the effectiveness of “housing entitlements” that were (a) issued and in effect prior to March 4, 2020 and (b) set to expire prior to December 31, 2021. All such qualifying housing entitlements will now remain valid for an additional period of eighteen (18) months.

Section 65914.5 broadly defines a “housing entitlement” to include any of the following:

- A legislative, adjudicative, administrative, or any other kind of approval, permit, or other entitlement necessary for, or pertaining to, a housing development project issued by a state agency;

- An approval, permit, or other entitlement issued by a local agency for a housing development project that is subject to the Permit Streamlining Act (Cal. Gov. Code § 65920 et seq);

- A ministerial approval, permit, or entitlement by a local agency required as a prerequisite to the issuance of a building permit for a housing development project;

- Any requirement to submit an application for a building permit within a specified time period after the effective date of a housing entitlement described in numbers 1 and 2 above; and

- A vested right associated with an approval, permit, or other entitlement described in numbers 1 through 4 above.

Notably, specifically excluded from the definition of a “housing entitlement” are: (a) development agreements authorized pursuant to California Government Code Section 65864; (b) approved or conditionally approved tentative maps which were previously extended for at least eighteen (18) months on or after March 4, 2020 pursuant to Government Code Section 66452.6; (c) preliminary applications under SB 330 (the Housing Crisis Act of 2019); and (d) applications for development approved under SB 35 (Cal. Gov. Code § 65913.4).

Further, housing entitlements which were previously granted an extension by any state or local agency on or after March 4, 2020, but before the effective date of AB 1561 (i.e. September 28, 2020), will not be further extended for an additional 18-month period so long as the initial extension period was for no less than eighteen (18) months.

The definition of a “housing development project” is broad and includes any of the following: (x) approved or conditionally approved tentative maps, vesting tentative maps, or tentative parcel maps for Subdivision Map Act compliance (Cal. Gov. Code § 66410 et seq); (y) residential developments; and (z) mixed-use developments in which at least two-thirds (2/3rds) of the square footage of the development is designated for residential use. For purposes of calculating the square footage devoted to residential use within a mixed-use development, the calculation must include any additional density, floor area, and units, and any other concession, incentive, or waiver of development standards obtained under California’s Density Bonus Law (Cal. Gov. Code § 65915); however, the square footage need not include any underground space such as a basement or underground parking garage.

AB 1561 makes clear that while the extension provision of Section 65914.5 applies to all cities, including charter cities, local governments are not precluded from further granting extensions to existing entitlements.

Gibson Dunn lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding these developments. For additional information, please contact any member of Gibson Dunn’s Real Estate or Land Use Group, or the following authors:

Doug Champion – Los Angeles (+1 213-229-7128, [email protected])

Amy Forbes – Los Angeles (+1 213-229-7151, [email protected])

Ben Saltsman – Los Angeles (+1 213-229-7480, [email protected])

Matthew Saria – Los Angeles (+1 213-229-7988, [email protected])

© 2020 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP

Attorney Advertising: The enclosed materials have been prepared for general informational purposes only and are not intended as legal advice.

While the COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted the practice of law in 2020, courts have continued to churn out important rulings impacting the media and entertainment industries. Here, Gibson Dunn’s Media, Entertainment and Technology Practice Group highlights some of those key cases and trends: from politically charged First Amendment cases to copyright battles over rock anthems, fictional pirates, and real-life music piracy.

I. Recent Litigation Highlights

A. First Amendment Litigation

1. President Trump’s Failed Efforts to Block Publication of Critical Books.

This presidential election year saw two efforts by the federal government and President Trump to enjoin the publication of forthcoming books critical of the current president. Both efforts to obtain a prior restraint order failed and the books were released, though one of the cases is far from over.

On June 20, 2020, the District Court for the District of Columbia rejected the U.S. government’s motion for a preliminary injunction and temporary restraining order to block former National Security Advisor John Bolton from publishing his memoir, The Room Where it Happened.[1] The United States filed its lawsuit on June 16, 2020, alleging that Bolton’s book contains sensitive information that could compromise national security, that its publication breached non-disclosure agreements that bound Bolton, and that Bolton abandoned the prepublication review process.[2] In addition to an injunction, the government seeks as a remedy a constructive trust over Bolton’s proceeds from the book. PEN American Center, Inc., Association of American Publishers, Inc., Dow Jones & Company, Inc., The New York Times Company, Reporters Committee or Freedom of the Press, The Washington Post, the ACLU and others filed amicus briefs opposing the government’s effort to enjoin publication, arguing, among other things, that the First Amendment prohibits prior restraints for any duration of time.[3] Rejecting the government’s motion, the district court held that, while the government is likely to succeed on the merits of its complaint, it did not establish that it would suffer irreparable injury absent an injunction.[4] Judge Lamberth had harsh words for Bolton, stating that—while not controlling as to that present motion—Bolton “has exposed his country to harm and himself to civil (and potentially criminal) liability.”[5] On July 30, 2020, the government filed a motion for summary judgment against Bolton.[6] On September 15, 2020, it was reported that the Justice Department had opened a criminal investigation into Bolton’s alleged disclosure of classified information in connection with his book.[7] On October 1, 2020, the district court denied Bolton’s motion to dismiss the government’s civil case against him.[8] [Disclosure: Gibson Dunn represented amicus PEN American Center, Inc. in opposing the government’s effort to enjoin publication.]

On July 13, 2020, the New York Supreme Court rejected a similar attempt by President Trump’s brother, Robert S. Trump—brought shortly before his death—to enjoin publication of their niece Mary Trump’s book, Too Much and Never Enough.[9] Robert Trump filed his motion for temporary restraining order and preliminary injunction against Mary Trump and her publisher, Simon and Schuster, on June 26, 2020, alleging that publication of Ms. Trump’s book would breach a confidentiality clause in a nearly 20-year-old settlement agreement among the Trump family regarding the president’s parents’ estates.[10] Ms. Trump argued, among other things, that a prior restraint is not a constitutionally permissible method of enforcing a settlement agreement’s confidentiality provision and that the contract Robert Trump invoked was not enforceable under the circumstances.[11] The Court agreed, finding that “in the vernacular of First year law students, ‘Con. Law trumps Contracts.’”[12] Ms. Trump’s book was released and became a best-seller. [Disclosure: Gibson Dunn represents Mary Trump in this lawsuit.]

2. Defamation Litigation

a. A Barrage of Defamation Claims, Settlements, Trials, and Dismissals.

The past year has been particularly active in the defamation arena. While media defendants have won some high-profile victories over slander and libel claims, such claims remain a threat, and plaintiffs continue to file lawsuits with headline-grabbing damages requests. Sarah Palin’s libel case against The New York Times Company—over a 2017 editorial that she alleges falsely tied her to a mass shooting—will proceed to trial in February 2021 after the judge denied dueling summary judgment motions and found that the case should be decided by a jury.[13] And this year, Nicholas Sandmann settled suits brought against The Washington Post and CNN over coverage of his viral-video encounter with a Native American activist at the 2019 March for Life rally in Washington D.C.[14] Sandmann still has pending suits against NBC, ABC News, CBS News, The New York Times, Gannett, and Rolling Stone.[15]

On the other hand, in December 2019, a Los Angeles jury determined that Elon Musk did not defame Vernon Unsworth when he called him a “pedo guy” during a name-calling spat on Twitter.[16] Moreover, over the past year, Congressman Devin Nunes has seen many of his defamation suits against media companies rebuffed, with courts recently dismissing his lawsuit against Esquire and journalist Ryan Lizza, and dismissing another suit against the political research firm Fusion GPS, though Nunes continues to pursue both actions.[17] Nunes also continues to try to sue Twitter and certain of its users for defamation, including a Republican political strategist and anonymous parody accounts belonging to a fake cow (Devin Nunes’ cow @DevinCow) and to Nunes’ “mother” (Devin Nunes’ Alt-Mom @NunesAlt), even after Twitter was dismissed from the case.[18] Nunes has also filed suits against McClatchy, The Washington Post, and CNN.[19] [Disclosure: Gibson Dunn represents The McClatchy Company in the suit filed by Nunes.]

b. Rachel Maddow Wins Dismissal of One America News Network Owner’s Defamation Claim.

On May 22, 2020, Judge Cynthia A. Bashant of the Southern District of California granted Rachel Maddow, MSNBC, NBCUniversal, and Comcast’s anti-SLAPP special motion to strike in response to a complaint filed by Herring Networks, Inc., owner of the conservative news outlet One America News (“OAN”).[20] Herring Networks filed its lawsuit in September 2019 over comments Ms. Maddow made during a broadcast of The Rachel Maddow Show. During that show, she commented on a Daily Beast article that reported how OAN employed an on-air reporter who also worked for Sputnik, a pro-Kremlin news organization funded by the Russian government. While reporting on the article, Ms. Maddow exclaimed, “the most obsequiously pro-Trump right wing news outlet in America really literally is paid Russian propaganda. Their on air U.S. politics reporter is paid by the Russian government to produce propaganda for that government.”[21] Herring Networks argued Ms. Maddow’s statement that the network “really literally is paid Russian propaganda” was false and defamatory.[22]

Ms. Maddow and the other defendants challenged Herring Networks’ suit via a motion to strike under California’s anti-SLAPP law, arguing that Ms. Maddow’s statement was fully protected opinion under the First Amendment and, in any event, was substantially true.[23] The court granted the defendants’ motion, explaining Ms. Maddow clearly outlined the basis for her opinions during the segment and “inserted her own colorful commentary” regarding the facts.[24] As such, the court found the statement was protected opinion as a matter of law and disagreed with Herring Networks’ argument that Ms. Maddow’s statement raised a factual issue for a jury. The court dismissed Herring Networks’ complaint with prejudice, and ordered the defendants to file a motion to recover their fees (as required by California’s anti-SLAPP law).[25] Herring Networks has filed a notice of appeal with the Ninth Circuit. [Disclosure: Gibson Dunn represents Ms. Maddow, MSNBC, NBCUniversal, and Comcast in this action.]

c. “Wolf of Wall Street” Libel Claim Fails.

In June 2020, the Second Circuit rejected a libel lawsuit filed against Paramount Pictures over the film “The Wolf of Wall Street,” in which Wall Street brokerage-firm attorney Andrew Greene alleged he was defamed by a fictional character in the film who Greene claimed resembled him.[26] Greene, an ex-employee of the financial firm portrayed in the film, alleged that the film featured a character that is “recognizable as him” and “depicted as engaging in behavior that defames his character.”[27] The District Court for the Eastern District of New York granted the defendants’ motion for summary judgment, holding that Greene failed to raise a genuine issue of material fact as to whether Paramount Pictures acted with knowledge or reckless disregard in making defamatory statements “of and concerning” Greene.[28]

The Second Circuit affirmed, holding that Greene’s claims failed as a matter of law because a reasonable jury would not find that Paramount Pictures acted with actual malice.[29] First, the Second Circuit found that Paramount Pictures “took appropriate steps to ensure that no one would be defamed by the Film.”[30] Those steps included reading the book and news articles on which the film was based and assigning characters fictitious names with no “specific real life analogue.”[31] Second, the circuit court found that “no reasonable viewer” of “The Wolf of Wall Street” would believe that Paramount Pictures intended the character in the film as a depiction of Greene, as Paramount Pictures knew the film character was a fictitious, composite character.[32] Also, Greene worked as head of the corporate finance department at the financial firm portrayed in the film, while the character at issue worked as a broker on the trading floor.[33] Finally, the film included a disclaimer that characters in the film were fictionalized.[34]

3. Right of Publicity

a. New York Considers New Right of Publicity Law.

In July 2020, both houses of the New York Legislature unanimously passed a much-anticipated proposed right of publicity bill, which awaits signature by Governor Andrew Cuomo.[35] The bill, Senate Bill S5959D/Assembly Bill No. A05605B, would replace New York Civil Rights Law § 50 and changes the right of publicity landscape in the state.[36] Significantly, the bill makes a person’s right of publicity an independent property right that is freely transferable and creates postmortem rights for forty years after the death of an individual.[37] It further “protects a deceased performer’s digital replica in expressive works to protect against persons or corporations from misappropriating a professional performance.”[38]

Given the rise of pornographic deepfakes—“hyper-realistic manipulation of digital imagery that can alter images so effectively it’s largely impossible to tell real from fake”[39]—SAG-AFTRA called the bill’s passage “a remarkable step in the ongoing effort to protect our members, and all performers, from the exploitation of our images and voices – the very assets we use to make a living.”[40] But others, including the Motion Picture Association of America (“MPAA”) and the New York State Broadcasters Association, Inc., have voiced concerns about the bill’s implications, arguing it chills speech and presents First Amendment concerns.[41] Specifically, the MPAA argues that the bill’s language is vague and overbroad and interferes with the ability of filmmakers to tell stories inspired by real people and events.[42]

B. Profit Participation & Royalties

1. AMC Prevails in First The Walking Dead Profits Trial in California.

On July 22, 2020, following a bench trial, Judge Daniel Buckley of the Superior Court for the County of Los Angeles issued a sweeping ruling in favor of AMC in a profit participation action regarding the hit AMC series The Walking Dead.[43] This California lawsuit, governed by New York contract law, was brought by various show participants, including Robert Kirkman, David Alpert, and Gale Anne Hurd. The case also involved issues pertaining to spin-offs Fear the Walking Dead and Talking Dead. The profit participants alleged that AMC failed to properly account to them under their agreements, and Judge Buckley ordered the eight-day trial to resolve key, gateway issues of contractual interpretation.

Those issues included (1) whether AMC’s standard modified adjusted gross receipts definition (“MAGR Definition”) governed the calculation, reporting, and payment of MAGR to the plaintiffs; and (2) whether the affiliate transaction provision in certain plaintiffs’ agreements applied to AMC Network’s exhibition of The Walking Dead.[44]

Judge Buckley found that AMC’s standard MAGR Definition governed the calculation, reporting, and payment of MAGR to the plaintiffs, even where the MAGR exhibit was supplied after the plaintiffs signed their agreements. The court looked at the plain text of the parties’ agreements, which stated that “MAGR shall be defined, computed, accounted for and paid in accordance” with AMC’s MAGR Definition, and explained that “New York courts routinely uphold the right of one party to a contract to fix a material price term in the future.”[45] The court also noted that the plaintiffs bargained for and received particular MAGR protections in the agreements themselves.[46] Though the court found looking to extrinsic evidence was unnecessary, it explained how years of post-performance conduct only confirmed AMC’s position that its MAGR Definition controlled, with certain plaintiffs waiting four years to object to the MAGR Definition after they received it, all the while accepting payments from AMC under that definition.[47]

One of the plaintiffs’ key arguments was that the license fee imputed for AMC Network’s exhibition of The Walking Dead, which appeared in the MAGR Definition, was too low and not in compliance with the affiliate transaction provisions in their agreements. Those provisions required “‘AMC’s transactions with Affiliated Companies [to] be on monetary terms comparable with the terms on which AMC enters into similar transactions with unrelated third party distributors for comparable programs after arms’ length negotiation.”[48] The court held AMC Network’s exhibition of The Walking Dead was governed by the imputed license fee in the MAGR Definition, and that the affiliate transaction provisions only applied to transactions where the participant “has no seat at the table to negotiate. . . .”[49] The court found the provision did not apply to the kind of internal rights transfers the plaintiffs challenged.

Similar lawsuits over The Walking Dead were filed by CAA and Frank Darabont in New York.[50] The consolidated jury trial in these lawsuits is scheduled to begin in April 2021. [Disclosure: Gibson Dunn represents AMC in these actions.]

C. #MeToo Litigation

1. Ninth Circuit Revives Ashley Judd’s Harassment Claim against Harvey Weinstein.

On July 29, 2020, the Ninth Circuit ruled that the actor Ashley Judd could proceed with her sexual harassment claim against Harvey Weinstein. Ms. Judd filed her action alleging defamation, sexual harassment, intentional interference with prospective economic advantage, and unfair competition on April 30, 2018. Ms. Judd’s claims stemmed from events occurring in and around 1997, at which time Ms. Judd alleges Mr. Weinstein invited her, a Hollywood newcomer, to a “general” industry meeting at the Peninsula Hotel in Beverly Hills, where she was to seek advice and guidance. When Ms. Judd arrived, she was directed to Mr. Weinstein’s private hotel room, where Mr. Weinstein appeared in a bathrobe, asked to give Ms. Judd a massage, and asked her to watch him shower.

Judge Phillip Gutierrez of the Central District of California granted Mr. Weinstein’s motion to dismiss Ms. Judd’s sexual harassment claim, brought pursuant to California Civil Code section 51.9, finding Ms. Judd and Mr. Weinstein’s relationship did not fall within the definition of a “business, service, or professional relationship” under the statute. The court nonetheless explained that “an appellate decision on these important issues could provide needed guidance to lower courts applying § 51.9.” Ms. Judd appealed the dismissal of her sexual harassment claim to the Ninth Circuit.

Reversing the district court, the Ninth Circuit explained that “[Ms. Judd’s and Mr. Weinstein’s] relationship consisted of an inherent power imbalance wherein Weinstein was uniquely situated to exercise coercion or leverage over Judd by virtue of his professional position and influence as a top producer in Hollywood.”[51] The court held that section 51.9 does, in fact, cover such business or professional relationships where there is an inherent power imbalance.[52] [Disclosure: Gibson Dunn represents Ashley Judd in this action.]

D. Music Industry Litigation

1. Led Zeppelin Prevails in En Banc “Stairway” Ruling.

On March 9, 2020, the Ninth Circuit, sitting en banc, reinstated a Los Angeles jury’s 2016 verdict clearing Led Zeppelin of infringing the band Spirit’s song “Taurus.”[53] Michael Skidmore, the trustee of for the estate of Spirit’s founding member Randy Wolfe (pka Randy California), had alleged that the opening riff of “Stairway to Heaven” is substantially similar to “Taurus,” and infringed Wolfe’s copyright in the composition. In 2016, the jury found no substantial similarity between “Taurus” and the rock anthem under the extrinsic test for unlawful appropriation. But in September 2018, a Ninth Circuit three-judge panel vacated the verdict and remanded the case for a new trial.[54] The three-judge panel found that lack of an instruction explaining copyrights that cover the selection and arrangement of music, combined with an allegedly faulty instruction on the requisite element of originality prejudicially “undermined the heart of plaintiff’s argument.”[55]

The March 2020 en banc ruling overturned the panel in a detailed opinion, agreeing with U.S. District Judge R. Gary Klausner that the 1909 Copyright Act, not the 1976 Copyright Act, governed, and that only the bare-bones “deposit copy” of “Taurus” was properly introduced for comparison to “Stairway to Heaven.”[56] The en banc panel held that “[b]ecause the 1909 Copyright Act did not offer protection for sound recordings, [Spirit]’s one-page deposit copy defined the scope of the copyright at issue.”[57] Thus, it was not error for the district court to deny the plaintiff’s request to play for the jury sound recordings of “Taurus.”[58]

The en banc panel also rejected the “inverse ratio rule” previously adopted by the Ninth Circuit, under which it had “permitted a lower standard of proof of substantial similarity where there is a high degree of access.”[59] To preserve the inverse ratio rule, Judge McKeown wrote for the en banc panel, would “unfairly advantage[] those whose work is most accessible by lowering the standard of proof for similarity,” thereby benefitting “those with highly popular works.”[60] The “Stairway” case had been closely watched by the music industry and attracted numerous amicus at the court of appeals, including the U.S. Department of Justice supporting Led Zeppelin’s position on appeal. On October 5, 2020, the U.S. Supreme Court denied Skidmore’s petition for writ of certiorari.[61]

2. Labels’ and Publishers’ Billion-Dollar Verdict Against Cox Upheld.

On June 2, 2020, U.S. District Judge Liam O’Grady of the Eastern District of Virginia largely upheld a $1B verdict against Cox Communications won by over 50 records labels and music publishers, including Sony Music Entertainment, Universal Music Group, and Warner Bros. Records.[62]

Judge O’Grady rejected Cox’s contention that the evidence at trial was insufficient, concluding that there was “overwhelming” and “strong” evidence that Cox’s users illegally reproduced the sound recordings and distributed them over Cox’s network.[63] Further, there was “ample” evidence for the jury to conclude that Cox gained some direct benefit from the infringement and find Cox liable for vicarious copyright infringement.[64] Judge O’Grady emphasized evidence showing that “Cox looked at customers’ monthly payments when considering whether to terminate them for infringement.”[65]

Judge O’Grady also rejected Cox’s argument that the award was “grossly excessive.”[66] He noted that the per-work damages of $99,830.29 were more than $50,000 below the statutory maximum under the Copyright Act,[67] but ordered additional briefing on the issue of the calculation of the number of infringed works.[68]

3. Music Publishers and Peloton Reach Settlement in Copyright Suit After Dismissal of Cycling Company’s Counterclaims.

In March 2019, more than a dozen music publishers filed suit in New York federal court alleging popular fitness tech company Peloton failed to license songs for its online classes, thereby violating the publishers’ copyrights.[69] The publishers claimed over $150 million in damages for unlicensed uses of more than 1000 songs, with each use of an allegedly unlicensed song constituting a separate infringement because audiovisual “sync” licenses are issued on a per-video basis.[70] The publishers also alleged Peloton’s conduct was “deliberate and willful” because the company had obtained the necessary “sync” licenses from other music copyright owners.[71]

In response, Peloton counterclaimed against the publishers, alleging that any failure to obtain licenses was due to the National Music Publishers’ Association’s (“NMPA”) creation of a price fixing “cartel.”[72] Peloton alleged the NMPA both engaged in “horizontal collusion” to inflate prices in its own negotiations with the company and tortiously interfered with Peloton’s ability to negotiate with individual publishers.[73] On January 29, 2020, U.S. District Judge Denise Cote dismissed Peloton’s counterclaims without leave to amend, finding that Pelton failed define a “relevant market,” a necessary element to Peloton’s antitrust claim under Section 1 of the Sherman Act.[74] A month later, the case settled.

4. Second Circuit Upholds Copyright Win for Drake.

On February 3, 2020, the Second Circuit affirmed the Southern District of New York’s ruling that Drake did not violate copyright law by incorporating a 35-second clip of the song “Jimmy Smith Rap” into his song “Pound Cake” without a license.[75] The lawsuit began in April 2014, when the estate of Jimmy Smith sued Drake and Drake’s record labels and publishers for copyright infringement. The defendants moved for summary judgment, arguing that Drake’s use of the song was protected by the fair use doctrine.[76]

The District Court granted the defendants’ motion for summary judgment in May 2017.[77] In its 2020 ruling, the Second Circuit affirmed, finding Drake’s use of the song was protected by the fair use doctrine, as the use was “transformative.”[78] The Court stated that “‘Pound Cake’ criticizes the jazz-elitism that the ‘Jimmy Smith Rap’ espouses. By doing so, it uses the copyrighted work for a purpose, or imbues it with a character, different from that for which it was created.”[79] In addition, the Court found “no evidence that ‘Pound cake’ usurps demand for ‘Jimmy Smith Rap.’”[80] [Disclosure: Gibson Dunn represented one of the defendants in the action.]

E. Copyright Litigation

1. Ninth Circuit Revives Screenwriter’s Pirates of the Caribbean Copyright-Infringement Suit.

On July 22, 2020, the Ninth Circuit revived a screenwriter’s copyright-infringement suit against The Walt Disney Company alleging that the film Pirates of the Caribbean: Curse of the Black Pearl is substantially similar to plaintiff’s screenplay.[81] The district court had granted Disney’s Rule 12(b)(6) motion to dismiss on the grounds that the two works were not substantially similar as a matter of law.[82] In reversing, the Ninth Circuit acknowledged “striking differences between the two works,” but nonetheless found “the selection and arrangement of the similarities between them [to be] more than de minimis” and sufficient to warrant denial of Disney’s motion.[83]

The district court had noted the similarities between the works but concluded that many of the shared elements were “unprotected generic, pirate-movie tropes.”[84] The Ninth Circuit disagreed, explaining “it is difficult to know whether such elements are indeed unprotectible material” at the pleading stage, and further noting that additional evidence—including expert testimony—“would help inform the question of substantial similarity.”[85] According to the court, such additional evidence would be “particularly useful” given that “the blockbuster Pirates of the Caribbean film franchise may itself have shaped what are now considered pirate-movie tropes.”[86] Ultimately, because “[t]he district court erred by failing to compare the original selection and arrangement of the unprotectible elements between the two works,” the Ninth Circuit reversed the dismissal and remanded for further proceedings.[87] And on August 31, 2020, the Ninth Circuit denied Disney’s petition for panel rehearing and for rehearing en banc. Some commentators and practitioners have noted that the ruling appears to represent the latest in a shift away from the Ninth Circuit’s prior precedents that had generally leaned toward upholding dismissals of substantial similarity suits, representing a cautionary ruling for industry defendants.[88]

2. Copyright Act Preempts Lyrics Site Genius’s Claims Against Google.

On August 10, 2020, District Judge Margo Brodie dismissed Genius Media Group Inc.’s suit against Google. Genius Media had alleged in December 2019 that Google “misappropriated lyric transcriptions from its website.”[89] According to its complaint, Genius Media earns revenue by, among other things, licensing its database of high-quality lyrics to companies and generating ad revenue via traffic to its website.[90] In its complaint, Genius Media alleged that when users search for song lyrics, Google’s “Information Box”—which appears above the search results—displays complete song lyrics obtained from Genius Media’s website and thus reduces traffic to that site.[91] Genius Media sued Google for breach of contract, indemnification, unfair competition under New York and California law, and unjust enrichment.[92]

Judge Brodie determined, however, that Genius Media’s state law claims were preempted by the Copyright Act.[93] As an initial matter, Judge Brodie found that the transcribed song lyrics were among the works protected by the Copyright Act, and because the subject of Plaintiff’s claims was the transcribed lyrics, the subject-matter prong of the Copyright Act’s preemption test was met.[94] Judge Brodie additionally determined that Genius Media’s contract claims were “nothing more than claims seeking to enforce the copyright owner’s exclusive rights to protection from unauthorized reproduction of the lyrics and are therefore preempted”; however, Genius Media licensed, but did not own, the relevant copyrights.[95] The court found that Genius Media’s transcriptions are, in essence, derivative works, and held that “the case law is clear that only the original copyright owner has exclusive rights to authorize derivative works.”[96] Accordingly, the Court dismissed Genius Media’s complaint for failure to state a claim.[97]

______________________

[1] United States v. Bolton, No. 20-cv-1580, Order Denying Plaintiff’s Motion for Temporary Restraining Order and Preliminary Injunction (D. D.C. June 20, 2020).

[3] See, e.g., United States v. Bolton, No. 20-cv-1580, Brief of PEN American Center, Inc. as Amicus Curiae in Support of Defendant (D. D.C. June 19, 2020).

[4] United States v. Bolton, No. 20-cv-1580, Order Denying Plaintiff’s Motion for Temporary Restraining Order and Preliminary Injunction, *8 (D. D.C. June 20, 2020).

[6] United States v. Bolton, No. 20-cv-1580, Plaintiff’s Motion for Summary Judgment (D. D.C. July 30, 2020).

[7] Katie Benner, “Justice Dept. Opens Criminal Inquiry Into John Bolton’s Book,” N.Y. Times (Sept. 15, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/15/us/politics/john-bolton-book-criminal-investigation.html.

[8] Charlie Savage, “Government Lawsuit Over John Bolton’s Memoir May Proceed, Judge Rules,” N.Y. Times (Oct. 5, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/01/us/politics/john-bolton-book-proceeds-lawsuit.html.

[9] Trump v. Trump, No. 22020-51585, 2020 WL 4212159 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. July 13, 2020).

[10] Trump v. Trump, No. 22020-51585, Motion for Temporary Restraining Order and Preliminary Injunction (N.Y. Sup. Ct. June 26, 2020).

[11] Trump, 2020 WL 4212159, *14.

[13] Palin v. The New York Times Co., No. 17-cv-4853, Opinion and Order on Motions for Summary Judgment (S.D.N.Y Aug. 28, 2020).

[14] Ted Johnson, “Nick Sandmann, Student at Center of Viral Video, Settles Defamation Lawsuit Against Washington Post,” The Washington Post (July 24, 2020), https://deadline.com/2020/07/nick-sandmann-washington-post-defamation-1202994384/.

[15] Cameron Knight, “Sandmann files 5 more defamation lawsuits against media outlets,” Cincinnati Enquirer (Mar. 3, 2020), https://www.cincinnati.com/story/news/2020/03/03/sandmann-files-5-more-defamation-lawsuits-against-media-outlets/4938142002/.

[16] Lauren Berg, “Jury Says Elon Musk Didn’t Defame with ‘Pedo Guy’ Tweet,” Law360 (Dec. 6, 2019), https://www.law360.com/articles/1226249/jury-says-elon-musk-didn-t-defame-with-pedo-guy-tweet.

[17] Kate Irby, “Judge tells Devin Nunes for 3rd time he can’t sue Twitter over anonymous tweets,” The Fresno Bee (Aug. 14, 2020), https://www.fresnobee.com/news/california/article244958665.html.

[20] Herring Networks, Inc. v. Maddow, No. 19-cv-1713, Order Granting Defendants’ Special Motion to Strike (S.D. Cal. May 22, 2020).

[21] Id. at *3 (internal quotations omitted).

[26] Greene v. Paramount Pictures Corp., 813 F. App’x 728 (2d Cir. 2020).

[27] Id. at 730.

[28] Greene v. Paramount Pictures Corp., 340 F. Supp. 3d 161, 172 (E.D.N.Y. 2018).

[29] Greene, 813 F. App’x at 732.

[30] Id. at 731.

[31] Id.

[32] Id.

[33] Id.

[34] Id. at

[35] Senate Bill S5959D, 2019-2020 Legislative Session of The New York State Senate (last accessed Aug. 26, 2020), https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2019/s5959.

[36] Jennifer E. Rothman, New York Reintroduces Right of Publicity Bill with Dueling Versions, Rothman’s Roadmap to the Right of Publicity (May 22, 2019), https://www.rightofpublicityroadmap.com/news-commentary/new-york-reintroduces-right-publicity-bill-dueling-versions.

[37] Senate Bill S5959D, Summary Memo, supra note 35.

[39] Eriq Gardner, Deepfakes Pose Increasing Legal and Ethical Issues for Hollywood, The Hollywood Reporter (July 12, 2019), https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/thr-esq/deepfakes-pose-increasing-legal-ethical-issues-hollywood-1222978.

[40] David Robb, SAG-AFTRA Expects NY Gov. Andrew Cuomo To Sign Law Banning “Deepfake” Porn Face-Swapping, Deadline (July 28, 2020), https://deadline.com/2020/07/deepfakes-sag-aftra-expects-andrew-cuomo-to-sign-law-banning-face-swapping-porn-1202997577/.

[41] Ben Sheffner, New York vs. biopics? The state Legislature is poised to crack down on fact-inspired works of art, New York Daily News (June 18, 2019), https://www.nydailynews.com/opinion/ny-oped-stop-this-threat-to-free-speech-20190618-evesugulizgspk4reelegxiazu-story.html.

[43] Kirkman v. AMC Film Holdings, LLC, No. BC672124, 2020 WL 4364279 (Cal. Super. Ct. July 22, 2020).

[50] Darabont v. AMC Network Entertainment LLC, No. 654328/2013 (N.Y. Sup. Ct.); Darabont v. AMC Network Entertainment LLC, No. 650251/2018 (N.Y. Sup. Ct.).

[51] Judd v. Weinstein, 967 F.3d 952, 959 (9th Cir. 2020).

[53] Skidmore v. Led Zeppelin, 952 F.3d 1051 (9th Cir. 2020) (“Skidmore II”).

[54] Skidmore v. Led Zeppelin, 905 F.3d 1116 (9th Cir. 2018) (“Skidmore I”).

[56] Skidmore II, 952 F.3d at 1079.

[61] Bill Donahue, “Supreme Court Won’t Hear Led Zeppelin Copyright Fight,” Law360 (Oct. 5, 2020), https://www.law360.com/california/articles/1308109/supreme-court-won-t-hear-led-zeppelin-copyright-fight.

[62] Sony Music Entm’t v. Cox Commc’ns, Inc., No. 1:18-CV-950-LO-JFA (E.D. Va. June 2, 2020).

[69] Complaint, Downtown Music Publishing LLC, et al v. Peloton Interactive, Inc., No. 1:19-cv-02426 (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 19, 2019).

[72] Answer to Complaint and Counterclaims Against National Music Publishers’ Association, Inc. and Plaintiff Publishers, Downtown Music Publishing LLC, et al v. Peloton Interactive, Inc., No. 1:19-cv-02426-DLC, at 35–37 (S.D.N.Y. Apr. 30, 2019).

[74] Opinion & Order, Downtown Music Publishing LLC, et al v. Peloton Interactive, Inc., No. 1:19-cv-02426 (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 29, 2020).

[75] Smith v. Graham, No. 19-28, 799 F. App’x 36 (2d Cir. Feb. 3, 2020).

[76] Smith v. Cash Money Records, Inc., 253 F. Supp. 3d 737 (S.D.N.Y. 2017).

[78] Smith v. Graham, No. 19-28, 799 F. App’x. 36, 78 (2d Cir. Feb. 3, 2020).

[81] Alfred v. Walt Disney Co., — F. App’x —, 2020 WL 4207584 (9th Cir. July 22, 2020).

[88] See Bill Donahue, “9th Circ. Making It Harder for Studios To Beat Copyright Suits,” Law360 (July 29, 2020), https://www.law360.com/articles/1296112/9th-circ-making-it-harder-for-studios-to-beat-copyright-suits.

[89] Genius Media Grp. Inc. v. Google LLC, Case No. 1:19-cv-07279-MKB-VMS, Dkt. No. 22 at 1 (E.D.N.Y. Aug. 10, 2020).

[95] Id. at 16; see also id. at 23, 29 (similarly finding the unjust enrichment and state-law unfair-competition claims preempted by the Copyright Act).

[97] Id. at 36 (also denying Genius Media’s motion to remand to state court).

The following Gibson Dunn lawyers assisted in the preparation of this client update: Theodore Boutrous, Scott Edelman, Howard Hogan, Nathaniel Bach, Jonathan Soleimani, Dillon Westfall, Marissa Moshell, Kaylie Springer, Daniel Rubin, Sarah Scharf, and Abi Averill.

Gibson Dunn lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding these developments. Please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, the authors, or the following leaders and members of the firm’s Media, Entertainment & Technology Practice Group:

Theodore J. Boutrous, Jr. – Co-Chair, Litigation Practice, Los Angeles (+1 213-229-7000, [email protected])

Scott A. Edelman – Co-Chair, Media, Entertainment & Technology Practice, Los Angeles (+1 310-557-8061, [email protected])

Kevin Masuda – Co-Chair, Media, Entertainment & Technology Practice, Los Angeles (+1 213-229-7872, [email protected])

Orin Snyder – Co-Chair, Media, Entertainment & Technology Practice, New York (+1 212-351-2400, [email protected])

Howard S. Hogan – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3640, [email protected])

Ari Lanin – Los Angeles (+1 310-552-8581, [email protected])

Benyamin S. Ross – Los Angeles (+1 213-229-7048, [email protected])

Helgi C. Walker – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3599, [email protected])

Nathaniel L. Bach – Los Angeles (+1 213-229-7241,[email protected])

© 2020 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP

Attorney Advertising: The enclosed materials have been prepared for general informational purposes only and are not intended as legal advice.

Los Angeles partner Michael Farhang is the author of “New DOJ priority: targeting pandemic stimulus fraud” [PDF] published by the Daily Journal on October 5, 2020.

The Hong Kong Court of Appeal (Court of Appeal) recently reaffirmed[1], in the context of an application for an examination order of individuals (Respondents) residing in Hong Kong to obtain information which may enable partial satisfaction of a judgment debt under a judgment in proceedings in a foreign court to which neither the Respondents nor the companies of which they are officers were parties, that pre-trial discovery against non-party witness is not permitted, save within the limited scope of Norwich Pharmacal discovery.

1. Background Leading to the Application in Hong Kong

The applicants for the Hong Kong examination order (Applicants) obtained a judgment for US$100,738,980 (Judgment Debt) in the United States District Court, Western District of Washington at Seattle (Federal Court) against a number of judgment debtors.

The Applicants’ case was that based on the unaudited balance sheet of one of the judgment debtors (Judgment Debtor), there were receivables owed by some third parties to the Judgment Debtor, being US$18.9 million by an exempted limited partnership registered in Cayman Islands, and US$4 million by a company incorporated in the British Virgin Islands (respectively, the Two Sums and the Third Parties).

The Applicants were appointed by the King County Superior Court, State of Washington (State Court) as collecting agent to collect the receivables of the Judgment Debtor, including the Two Sums. Such receivables were to be applied to satisfy the Judgment Debt. The State Court subsequently clarified that it did not have jurisdiction over the Third Parties (as they had no place of business in the State of Washington) and it did not adjudicate on the issue of whether the Two Sums were owed by them to the Judgment Debtor, and held that the collection orders only placed the Applicants in the shoes of the Judgment Debtor for collection purposes and such orders could be made even though the State Court had no jurisdiction over the Third Parties.

Of importance to note is that the collection orders were not garnishee orders, and there is no evidence to suggest that the Federal Court and the State Court had the requisite personal jurisdiction over the Third Parties for garnishee proceedings. Further, the relevant transaction agreements between the Judgment Debtor and the Third Parties respectively had an exclusive jurisdiction clause, which provided that the agreements were governed by the laws in Hong Kong and subject to resolution solely in the Hong Kong Courts.

The Two Sums were disputed by the Third Parties, and their case was that it was the Judgment Debtor which owed them monies instead.

The Respondents, being the subjects of the examination order, are officers of the Third Parties, who reside in Hong Kong.

2. Procedural History in the Hong Kong Courts

The Federal Court issued two Letters of Request for an examination of the Respondents, the purpose of which was to allow the Applicants to obtain information regarding the Two Sums that may enable them to collect the monies owed to the Judgment Debtor which could be utilised to satisfy the Judgment Debt.

An ex parte application by way of an Originating Summons supported by the two Letters of Request to examine the Respondents were made by the Applicants and Master Lai of the Court of First Instance (CFI) granted an examination order (Examination Order).

The Respondents applied to set aside the Examination Order and/or to strike out the Applicants’ ex parte Originating Summons. Both applications were allowed by Recorder Yvonne Cheng SC (Judge) of the CFI.

The Applicants appealed against the decision of the Judge, which decision was upheld by the Court of Appeal.

3. Requirements under the Evidence Ordinance (Cap. 8) (Ordinance) in the Context of Evidence for Civil Proceedings in Other Jurisdictions

Whilst both sections 75(b) and 76(3) of the Ordinance are relevant in the circumstances[2], the Court of Appeal upheld the Judge’s decision based on section 76(3) alone. The analysis under paragraph 3.2 below on section 75(b) is included for completeness.

3.1 Section 76(3) – Pre-Trial Discovery Against Non-Party Witness Prohibited

Section 76 provides for the power of the Court of First Instance to give effect to an application for assistance in obtaining evidence for civil proceedings in foreign courts. Section 76(3) states that:

An order under this section shall not require any particular steps to be taken unless they are steps which can be required to be taken by way of obtaining evidence for the purposes of civil proceedings in the court making the order (whether or not proceedings of the same description as those to which the application for the order relates)…” (emphasis added)

The Judge held that the proposed examination was for pre-trial discovery against non-party witnesses, which is not permitted under Hong Kong law and prohibited by section 76(3), since the allegations of fact relied upon by the Applicants (in short, the Third Parties owed monies to the Judgment Debtor) were not live issues before and to be resolved by the Federal Court where the main action was concluded, and enforcement proceedings (i.e. garnishee proceedings) in which such allegations could be raised had not been instituted. As to the Applicants’ alternative case that after the examination of the Respondents they would “plot a course for collection depending on the evidence so obtained”, the judge held that the proposed examination was a fishing exercise.

The Court of Appeal agreed with the Judge’s decision, and made, inter alia, the following remarks:

- Hong Kong has adopted the common law position that there is no pre-trial discovery against non-party witnesses other than those falling within the limited scope of Norwich Pharmacal discovery (i.e. discovery against third parties who got innocently mixed up in the wrongdoings of others);

- whether the assistance request falls foul of section 76(3) on account of fishing must be a matter for the judge in Hong Kong by reference to Hong Kong laws rather than US laws under which the permissible scope of discovery is wider. Whilst examination which is investigatory in nature (in contrast to eliciting admissible evidence) is allowed under US laws, it is not permitted under Hong Kong laws; and

- obtaining information from a non-party witness by way of post-judgment discovery in aid of execution, whilst permissible under US laws, is not a permissible procedure in Hong Kong, noting that if a judgment creditor has sufficient ground to support the application for a garnishee order in respect of a debt due to a judgment debtor, the judgment creditor has to commence garnishee proceedings first before he can obtain directions for determination of the liability of the garnishee (including directions for discovery as necessary)[3].

3.2 Section 75(b) – Obtaining Evidence for the Purposes of Civil Proceedings

Section 75 provides for the requirements to be fulfilled in an application for assistance. Section 75(b) provides that:

“Where an application is made to the Court of First Instance for an order for evidence to be obtained in Hong Kong and the court is satisfied that the evidence to which the application relates is to be obtained for the purposes of civil proceedings which either have been instituted before the requesting court or whose institution before that court is contemplated, the Court of First Instance shall have the powers conferred on it by this part.” (emphasis added)

The central issue under this section is therefore whether evidence is to be obtained for the purposes of civil proceedings, instituted or contemplated, before the requesting court.

The Judge, without the benefit of expert evidence on US law from the Applicants which was set out in an affirmation[4], ruled that the requirement was not satisfied because the evidence was not obtained for the purposes of civil proceedings which either have been instituted before the Federal Court or whose institution was contemplated.

The Judge rejected that the very application for discovery leading to the Federal Court’s request for evidence could constitute civil proceedings within the meaning of section 75(b) as a matter of construction, since it would render the section redundant. Further, since there was no evidence that the Applicants could establish the Federal Court’s jurisdiction over the Third Parties, it could not be said that proceedings against the Third Parties in the said court for enforcement of the judgment were contemplated.

The Court of Appeal, however, left the issue open, since it disagreed with the Judge on the admissibility of the Applicants’ expert evidence on US law.[5]

Notwithstanding such disagreement and that it was prepared to assume that under US law, the obtaining of information to facilitate the “plotting of the next course of action” would be regarded as obtaining evidence for use in the Federal Court proceedings, the Court of Appeal took the view that it also had to be established that the relevant proceedings were proceedings in a civil or commercial manner in the requested jurisdiction, i.e. Hong Kong court, in addition to the requesting jurisdiction.

In this regard, the Court of Appeal considered that the mere facilitation of the Applicants to act as collection agent did not qualify as civil proceedings in Hong Kong. Whilst discovery procedure is a form of civil proceedings in Hong Kong, such discovery would not be permitted against non-party witnesses, other than the limited form of Norwich Pharmacal discovery.

4. Conclusion

It is clear from the decisions of the Judge and the Court of Appeal that to obtain an order for assistance in obtaining evidence for civil proceedings in a foreign court, such obtaining of evidence must be permissible under the laws of Hong Kong. It is not sufficient that it is only permissible under the laws of the requesting jurisdiction (which may be implied by the Letter of Request issued by the foreign court). On this note, pre-action discovery against non-party witness is not permitted in Hong Kong save for Norwich Pharmacal discovery.

_______________________

[1] Re a civil matter now pending in United States District Court for the Western District of Washington at Seattle under No 2:13-CV-1034 MJP ([2020] HKCA 766). The presiding judges were Hon Lam VP, Chu JA and G Lam J. A copy of the judgement of the Court of Appeal is available here. The judgment of the Court of First Instance ([2019] HKCFI 1738) is available here.

[2] The Respondents also argued that (1) there were material non-disclosures on the Applicants’ part when they took out the ex parte application for the Examination Order and (2) the Examination Order contravened section 6 of the Protection of Trading Interests Ordinance (Cap. 471). However, these were not the focus of the Judge or the Court of Appeal and accordingly, are not the focus of this alert.

[3] The Applicants did not commence garnishee proceedings against the Third Parties since the Federal Court did not appear to have personal jurisdiction over the Third Parties and they were also unable to say that the Two Sums were actually due from these entities to the Judgment Debtor. Further, the Applicants also faced the difficulty of the exclusive choice of forum clauses in the agreements governing the transactions between the Judgment Debtor and the Third Parties. However, these issues were not put before the Federal Court in the application for the Letters of Request and accordingly, the Federal Court had no opportunity to address it. The Court of Appeal remarked that if the Applicants wished to rely on the use of evidence of the Respondents in garnishee proceedings against the Third Parties, they should have at least alluded to such basis in their motion for application for the Letters of Request.

[4] The Judge ruled that such evidence was not admissible on the basis that there was no expert declaration in accordance with Order 38 Rule 37C of the Rules of the High Court (RHC). The expert for the Applicants, being the general counsel of the Applicants (who was heavily engaged in the present dispute), felt that he was unable to give an expert declaration.

[5] The Court of Appeal was inclined to take the view that the prohibition against admissibility for lack of expert declaration under Order 38 Rule 37C of the RHC does not apply automatically to expert evidence set out in affidavits or affirmations adduced under Order 38 Rule 2(3) (as opposed to expert reports filed for trial pursuant to directions given under Order 38 Rule 6 regarding proceedings commenced by, inter alia, Originating Summons), being an exception under Order 38 Rule 36(2) .

Gibson Dunn’s lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding these developments. Please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, or the authors and the following lawyers in the Litigation Practice Group of the firm in Hong Kong:

Brian Gilchrist (+852 2214 3820, [email protected])

Elaine Chen (+852 2214 3821, [email protected])

Emily Chan (+852 2214 3825, [email protected])