Developments in the Defense of Financial Institutions – The International Reach of the U.S. Money Laundering Statutes

Client Alert | January 9, 2020

Our clients frequently inquire about precisely when U.S. money laundering laws provide jurisdiction to reach conduct that occurred outside of the United States. In the past decade, U.S. courts have reiterated that there is a presumption against statutes applying extraterritorially,[1] and explicitly narrowed the extraterritorial reach of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (“FCPA”)[2] and the wire fraud statute.[3] But the extraterritorial reach of the U.S. money laundering statutes—18 U.S.C. §§ 1956 and 1957—remains uncabined and increasingly has been used by the U.S. Department of Justice (“DOJ”) to prosecute crimes with little nexus to the United States. Understanding the breadth of the money laundering statutes is vital for financial institutions because these organizations often can become entangled in a U.S. government investigation of potential money laundering by third parties, even though the financial institution was only a conduit for the transactions.

This alert is part of a series of regular analyses of the unique impact of white collar issues on financial institutions. In this edition, we examine how DOJ has stretched U.S. money laundering statutes—perhaps to a breaking point—to reach conduct that occurred outside of the United States. We begin by providing a general overview of the U.S. money laundering statutes. From there, we discuss how DOJ has relied on a broad interpretation of “financial transactions” that occur “in whole or in part in the United States” to reach, for instance, conduct that occurred entirely outside of the United States and included only a correspondent banking transaction that cleared in the United States. And while courts have largely agreed with DOJ’s interpretation of the money laundering statutes, a recent acquittal by a jury in Brooklyn in a case involving money laundering charges with little nexus to the United States shows that juries occasionally may provide a check on the extraterritorial application of the money laundering statutes—for those willing to risk trial. Next, we discuss three recent, prominent examples—the FIFA corruption cases, the 1MDB fraud civil forfeitures, and the recent Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (“PDVSA”) indictments—that demonstrate how DOJ has increasingly used the money laundering statutes in recent years to police corruption and bribery abroad. The alert concludes by illustrating the risks that the broad reach of the money laundering statutes can have for financial institutions.

1. The U.S. Money Laundering Statutes and Their Extraterritorial Application

In 1980, now-Judge Rakoff wrote that “[t]o federal prosecutors of white collar crime, the mail fraud statute is our Stradivarius, our Colt 45, our Louisville Slugger, our Cuisinart—and our true love.”[4] In 2020, the money laundering statutes now play as an entire string quartet for many prosecutors, particularly when conduct occurs outside of the United States.

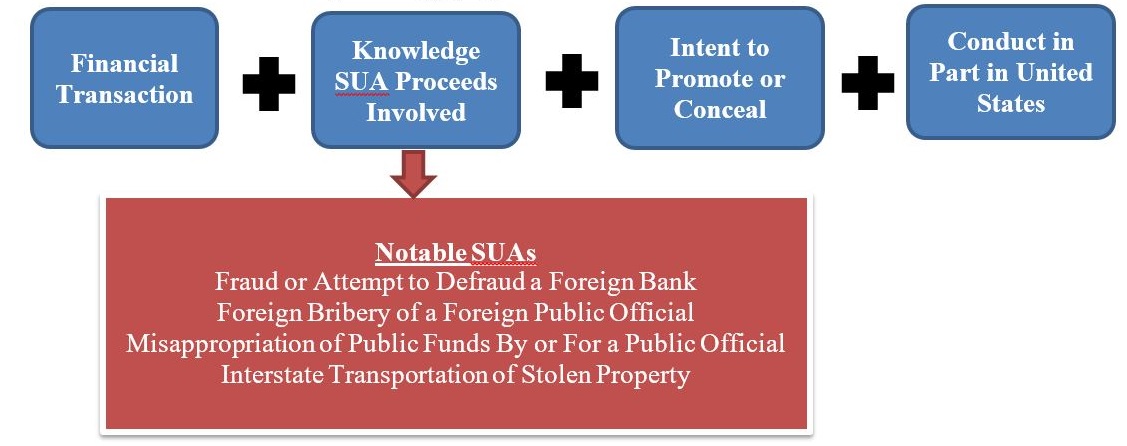

Title 18, Sections 1956 and 1957 are the primary statutes that proscribe money laundering. “Section 1956 penalizes the knowing and intentional transportation or transfer of monetary proceeds from specified unlawful activities, while § 1957 addresses transactions involving criminally derived property exceeding $10,000 in value.” Whitfield v. United States, 543 U.S. 209, 212-13 (2005). To prosecute a violation of Section 1956, the government must prove that: (1) a person engaged in a financial transaction, (2) knowing that the transaction involved the proceeds of some form of unlawful activity (a “Specified Unlawful Activity” or “SUA”),[5] and (3) the person intended to promote an SUA or conceal the proceeds of an SUA.[6] And if the person is not located in the United States, Section 1956 provides that there is extraterritorial jurisdiction if the transaction in question exceeds $10,000 and “in the case of a non-United States citizen, the conduct occurs in part in the United States.”[7] The word “conducts” is defined elsewhere in the statute as “includ[ing] initiating, concluding, or participating in initiating, or concluding a transaction.”[8] Putting it all together, establishing a violation of Section 1956 by a non-U.S. citizen abroad requires:

Figure 1: Applying Section 1956 Extraterritorially

Section 1957 is the spending statute, involving substantially the same elements as Section 1956 but substituting a requirement that a defendant spend proceeds of criminal activity for the requirement that a defendant intend to promote or conceal an SUA.[9]

a. “Financial Transaction” and Correspondent Banking

Although the term “financial transaction” might at first blush seem to limit the reach of money laundering liability, the reality is that federal prosecutors have repeatedly and successfully pushed the boundaries of the types of value exchanges that qualify as “financial transactions.” As one commentator has noted, “virtually anything that can be done with money is a financial transaction—whether it involves a financial institution, another kind of business, or even private individuals.”[10] Indeed, courts have confirmed that the reach of money laundering statutes extends beyond traditional money. One such example involves the prosecution of the creator of the dark web marketplace Silk Road. In 2013, federal authorities shut down Silk Road, which they alleged was “the most sophisticated and extensive criminal marketplace on the Internet” that permitted users to anonymously buy and sell illicit goods and services, including malicious software and drugs.[11] Silk Road’s creator, Ross William Ulbricht, was charged with, among other things, conspiracy to commit money laundering under Section 1956.[12] The subsequent proceedings focused in large part on the meaning of “financial transactions” as used in Section 1956 and specifically, whether transactions involving Bitcoin can qualify as “financial transactions” under the statute. Noting that “financial transaction” is broadly defined, the district court reasoned that because Bitcoin can be used to buy things, transactions involving Bitcoin necessarily involve the “movement of funds” and thus qualify as “financial transactions” under Section 1956.[13]

In addition to broadly interpreting “financial transaction,” DOJ also has taken an expansive view of what constitutes a transaction occurring “in part in the United States”—a requirement to assert extraterritorial jurisdiction over a non-U.S. citizen.[14] One area where DOJ has repeatedly pushed the envelope involves correspondent banking transactions.

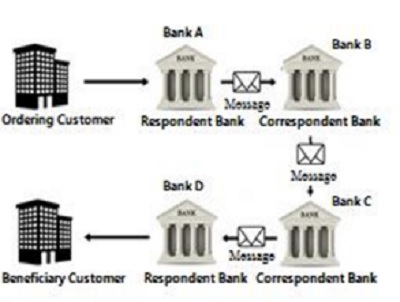

Correspondent banking transactions are used to facilitate cross-border transactions that occur between two parties using different financial institutions that lack a direct relationship. As an example, if a French company (the “Ordering Customer”) maintains its accounts at a French financial institution and wants to send money to a Turkish company (the “Beneficiary Customer”) that maintains its accounts at a Turkish financial institution, and if the French and Turkish banks lack a direct relationship, then often those banks will process the transaction using one or more correspondent accounts in the United States. An example of this process is depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Correspondent Banking Transactions[15]

Although correspondent banking transactions can occur using a number of predominant currencies, such as euros, yen, and renminbi, U.S. dollar payments account for about 50 percent of correspondent banking transactions.[16] Not only that, but “[t]here are indications that correspondent banking activities in US dollars are increasingly concentrated in US banks and that non-US banks are increasingly withdrawing from providing services in this currency.”[17] As a result, banks in the United States play an enormous role in correspondent banking transactions.

Given the continued centrality of the U.S. financial system, when confronted with misconduct taking place entirely outside of the United States, federal prosecutors are often able to identify downstream correspondent banking transactions in the United States involving the proceeds of that misconduct. On the basis that the correspondent banking transaction qualifies as a financial transaction occurring in part in the United States, prosecutors have used this hook to establish jurisdiction under the money laundering statutes. Two notable examples are discussed below.

i. Prevezon Holdings

The Prevezon Holdings case confirmed DOJ’s ability to use correspondent banking transactions as a jurisdictional hook for conduct occurring overseas. The case arose from an alleged $230 million fraud scheme that a Russian criminal organization and Russian government officials perpetrated against hedge fund Hermitage Capital Management Limited.[18] In 2013, DOJ filed a civil forfeiture complaint alleging that (1) the criminal organization stole the corporate identities of certain Hermitage portfolio companies by re-registering them in the names of members of the organization. Then, (2) other members of the organization allegedly filed bogus lawsuits against the Hermitage entities based on forged and backdated documents. Later, (3) the co-conspirators purporting to represent the Hermitage portfolio companies confessed to all of the claims against them, leading the courts to award money judgments against the Hermitage entities. Finally, (4) the representatives of the purported Hermitage entities then fraudulently obtained money judgments to apply for some $230 million in fraudulent tax refunds.[19] DOJ alleged that this fraud scheme constituted several distinct crimes, all of which were SUAs supporting money laundering violations. DOJ then sought forfeiture of bank accounts and real property allegedly traceable to those money laundering violations.

The parties challenging DOJ’s forfeiture action (the “claimants”) moved for summary judgment on certain of the SUAs, claiming that those SUAs, including Interstate Transportation of Stolen Property (“ITSP,” 18 U.S.C. § 2314), did not apply extraterritorially. The district court rejected claimants’ challenge to the ITSP SUA. The court held that Section 2314 does not, by its terms, apply extraterritorially.[20] Nevertheless, the court found the case involved a permissible domestic application of the statute because it involved correspondent banking transactions. Specifically, the court held that “[t]he use of correspondent banks in foreign transactions between foreign parties constitutes domestic conduct within [the statute’s] reach, especially where bank accounts are the principal means through which the relevant conduct arises.”[21] In support of this holding, the court described U.S. correspondent banks as “necessary conduits” to accomplish the four U.S. dollar transactions cited by the government, which “could not have been completed without the services of these U.S. correspondent banks,” even though the sender and recipient of the funds involved in each of these transactions were foreign parties.[22] The court also rejected claimants’ argument that they would have had to have “purposefully availed” themselves of the services of the correspondent banks, on the basis that this interpretation would frustrate the purpose of Section 2314 given that “aside from physically carrying currency across the U.S. border, it is hard to imagine what types of domestic conduct other than use of correspondent banks could be alleged to displace the presumption against extraterritoriality in a statute addressing the transportation of stolen property.”[23]

ii. Boustani

The December 2019 acquittal of a Lebanese businessman on trial in the Eastern District of New York marks an unusual setback in DOJ’s otherwise successful efforts to expand its overseas jurisdiction by using the money laundering statutes and correspondent banking transactions.

Jean Boustani was an executive at the Abu Dhabi-based shipping company Privinvest Group (“Privinvest”).[24] According to prosecutors, three Mozambique-owned companies borrowed over $2 billion through loans that were guaranteed by the Mozambican government.[25] Although these loans were supposed to be used for maritime projects with Privinvest, the government alleged that Boustani and his co-conspirators created the maritime projects as “fronts to raise as much money as possible to enrich themselves,” ultimately diverting over $200 million from the loan funds for bribes and kickbacks to themselves, Mozambican government officials, and Credit Suisse bankers.[26] According to the indictment, Boustani himself received approximately $15 million from the proceeds of Privinvest’s fraudulent scheme, paid in a series of wire transfers, many of which were paid through a correspondent bank account in New York City.[27]

Boustani did not engage directly in any activity in the United States, and he filed a motion to dismiss arguing that, with respect to a conspiracy to commit money laundering charge, as a non-U.S. citizen he must participate in “initiating” or “concluding” a transaction in the United States to come under the extraterritorial reach of 18 U.S.C. § 1956(f).[28] Specifically, he argued that “[a]ccounting interactions between foreign banks and their clearing banks in the U.S. does not constitute domestic conduct . . . as Section 1956(f) requires.”[29] In response, prosecutors argued that Boustani “systematically directed $200 million of U.S. denominated bribe and kickback payments through the U.S. financial system using U.S. correspondent accounts”[30] and that such correspondent banking transactions are sufficient to allow for the extraterritorial application of Section 1956.[31]

The court agreed with the government’s position. In denying the motion to dismiss, the court held that correspondent banking transactions occurring in the United States are sufficient to satisfy the jurisdictional requirements of 18 U.S.C. § 1956(f).[32] It cited to “ample factual allegations” that U.S. individuals and entities purchased interests in the loans at issue by wiring funds originating in the United States to locations outside the United States and that Boustani personally directed the payment of bribe transactions in U.S. dollars through the United States, describing this as “precisely the type of conduct Congress focused on prohibiting when enacting the money laundering provisions with which [Boustani] is charged.”[33]

The jury, however, was unconvinced. After a roughly seven-week trial, Boustani was acquitted on all charges on December 2, 2019.[34] The jurors who spoke to reporters after the verdict said that a major issue for the jury was whether or not U.S. charges were properly brought against Boustani, an individual who had never set foot in the United States before his arrest.[35] The jury foreman commented, “I think as a team, we couldn’t see how this was related to the Eastern District of New York.”[36] Another juror echoed this sentiment, adding, “We couldn’t find any evidence of a tie to the Eastern District. . . . That’s why we acquitted.”[37]

The Boustani case illustrates that even if courts are willing to accept the position that the use of correspondent banks in foreign transactions between foreign parties constitutes domestic conduct within the reach of the money laundering statute, juries may be less willing to do so.

b. Using “Specified Unlawful Activities” to Target Conduct Abroad

Another way in which the U.S. money laundering statutes reach broadly is that the range of crimes that qualify as SUAs for purposes of Sections 1956 and 1957 is virtually without limit. Generally speaking, most federal felonies will qualify. More expansively, however, the money laundering statutes include specific foreign crimes that also qualify as SUAs. For example, bribery of a public official in violation of a foreign nation’s bribery laws will qualify as an SUA.[38] Similarly, fraud on a foreign bank in violation of a foreign nation’s fraud laws qualifies as an SUA.[39] In addition to taking an expansive view of what constitutes a “financial transaction” and when it occurs “in part in the United States,” DOJ also has increasingly used the foreign predicates of the money laundering statute to prosecute overseas conduct involving corruption or bribery. This subsection discusses a few notable recent examples.

i. FIFA

In May 2015, the United States shocked the soccer world when it announced indictments of nine Fédération Internationale de Football Association (“FIFA”) officials and five corporate executives in connection with a long-running investigation into bribery and corruption in the world of organized soccer.[40] Over a 24-year period, the defendants allegedly paid and solicited bribes and kickbacks relating to, among other things, media and marketing rights to soccer tournaments, the selection of a host country for the 2010 FIFA World Cup, and the 2011 FIFA presidential elections.[41] The defendants included high-level officials in FIFA and its constituent regional organizations, as well as co-conspirators involved in soccer-related marketing (e.g., Traffic Sports USA), broadcasting (e.g., Valente Corp.), and sponsorship (e.g., International Soccer Marketing, Inc.).[42] Defendants were charged with money laundering under Section 1956(a)(2)(A) for transferring funds to promote wire fraud, an SUA.[43] Two defendants were convicted at trial.[44] The majority of the remaining defendants have pleaded guilty and agreed to forfeitures.[45]

One of the defendants, Juan Ángel Napout, challenged the extraterritorial application of the U.S. money laundering statutes. At various points during the alleged wrongdoing, Napout served as the vice president of FIFA and the president of the Confederación Sudamericana de Fútbol (FIFA’s South American confederation).[46] Napout was accused of using U.S. wires and financial institutions to receive bribes for the broadcasting and commercial rights to the Copa Libertadores and Copa America Centenario tournaments.[47] He argued that the U.S. money laundering statutes do not apply extraterritorially to him and that, regardless, this exercise of extraterritorial jurisdiction was unreasonable.[48] The district court rejected these arguments, concluding that extraterritorial jurisdiction was proper because the government satisfied the two requirements in 18 U.S.C. § 1956(f): the $10,000 threshold and conduct that occurred “in part” in the United States.[49] Notably, at trial, the jury acquitted Napout of the two money laundering charges against him but convicted him on the other three charges (RICO conspiracy and two counts of wire fraud).[50] At the same trial, another defendant, José Marin, was charged with seven counts, including two for conspiracy to commit money laundering. Marin was acquitted on one of the money laundering counts but convicted on all others.[51]

ii. 1MDB

The 1MDB scandal is “one of the world’s greatest financial scandals.”[52] Between 2009 to 2014, Jho Low, a Malaysian businessman, allegedly orchestrated a scheme to pilfer approximately $4.5 billion from 1 Malaysia Development Berhad (“1MDB”), a Malaysian sovereign wealth fund created to pursue projects for the benefit of Malaysia and its people.[53] Low allegedly used that money to fund a lavish lifestyle including buying various properties in the United States and running up $85 million in gambling debts at Las Vegas casinos.[54] The former Prime Minister of Malaysia, Rajib Nazak, also personally benefited from the scandal, allegedly pocketing around $681 million.[55] Additionally, his stepson, Riza Aziz, used proceeds from the scandal to fund Red Granite Pictures, a U.S. movie production company, which produced “The Wolf of Wall Street,” among other films.[56]

In 2016, DOJ filed the first of a number of civil forfeiture actions against assets linked to funds pilfered from 1MDB, totaling about $1.7 billion.[57] As the basis of the forfeiture, DOJ asserted a number of different violations of the U.S. money laundering statutes on the basis of four SUAs.[58]

In March 2018, Red Granite Pictures entered into a settlement agreement with the DOJ to resolve the allegations in the 2016 civil forfeiture action.[59] On October 30, 2019, DOJ announced the settlement of a civil forfeiture action against more than $700 million in assets held by Low in the United States, United Kingdom and Switzerland, including properties in New York, Los Angeles, and London, a luxury yacht valued at over $120 million, a private jet, and valuable artwork.[60] Although neither Red Granite Pictures nor Low challenged the extraterritoriality of the U.S. money laundering statute as applied to their property, the cases nevertheless serve as noteworthy examples of DOJ using its authority under the money laundering statutes to police political corruption abroad.

iii. PDVSA

To date, more than 20 people have been charged in connection with a scheme to solicit and pay bribes to officials at and embezzle money from the state-owned oil company in Venezuela, Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A.[61] The indictments charge money laundering arising from several SUAs, including bribery of a Venezuelan public official.[62]

Many of the defendants have pled guilty to the charges, but the charges against two former government officials, Nervis Villalobos and Rafael Reiter, remain pending.[63] In March 2019, Villalobos filed a motion to dismiss the FCPA and money laundering claims against him on the basis that these statutes do not provide for extraterritorial jurisdiction.[64] As to the money laundering charges, he argued that “[e]xtraterritorial jurisdiction over a non-citizen cannot be based on a coconspirator’s conduct in the United States,” and that extraterritorial application of the money laundering statute would violate international law and the due process clause.[65] As of this writing, the court has not ruled on the motion.

2. The Risks to Financial Institutions

The degree to which the U.S. money laundering statutes can reach extraterritorial conduct outside the United States has important implications for financial institutions. Prosecutions of foreign conduct under the money laundering statutes frequently involve high-profile scandals, as shown above. Financial institutions are often drawn into these newsworthy investigations. In the wake of the FIFA indictments, for instance, “[f]ederal prosecutors said they were also investigating financial institutions to see whether they were aware of aiding in the launder of bribe payments.”[66] Indeed, more than half a dozen banks reportedly received inquiries from law enforcement related to the FIFA scandal.[67]

At a minimum, cooperating with these investigations is time-consuming and costly. The investigations can also create legal risk for financial institutions. In the United States, “federal law generally imposes liability on a corporation for the criminal acts of its agents taken on behalf of the corporation and within the scope of the agent’s authority via the principle of respondeat superior, unless the offense conduct solely furthered the employee’s interests at the employer’s expense (for instance, where the employee was embezzling from the employer).”[68] And prosecutors can satisfy the intent required by arguing that individual employees were “deliberately ignorant” of or “willfully blind” to, for instance, clearing suspicious transactions.[69]

The wide scope of potential corporate criminal liability in the United States is often surprising to our clients, particularly those with experience overseas where the breadth of corporate liability is narrower than in the United States. As one article explained, the respondeat superior doctrine is “exceedingly broad” as “it imposes liability regardless of the agent’s position in the organization” and “does not discriminate” in that “the multinational corporation with thousands of employees whose field-level salesman commits a criminal act is as criminally responsible as the small corporation whose president and sole stockholder engages in criminal conduct.”[70]

Given the breadth of corporate criminal liability, DOJ applies a 10-factor equitable analysis to determine whether to impute individual employee liability to the corporate employer. These 10 factors are the “Principles of Federal Prosecution of Business Organizations,” and are often referred to by the shorthand term “Filip Factors.” The factors include considerations such as the corporation’s cooperation, the pervasiveness of the wrongdoing, and other considerations meant to guide DOJ’s discretion regarding whether to pursue a corporate resolution.[71] They are not equally weighted (indeed, there is no specific weighting attached to each, and the DOJ’s analysis will not be mathematically precise). Financial institutions should continually assess, both proactively and in the event misconduct occurs, the actions that can be taken to ensure that they can persuasively argue that, even if there is legal liability under the doctrine of respondeat superior, prosecution is nevertheless unwarranted under the Filip Factors.

3. Conclusion

In recent years, DOJ has expansively applied the money laundering statutes to reach extraterritorial conduct occurring almost entirely overseas. Indeed, a mere correspondent banking transaction in the United States has been used by DOJ as the hook to prosecute foreign conduct under the U.S. money laundering statutes. Because of the extraordinary breadth of corporate criminal liability in the United States, combined with the reach of the money laundering statutes, the key in any inquiry is to quickly assess and address prosecutors’ interests in the institution as a subject of the investigation.

____________________

[1] Morrison v. National Australia Bank Ltd., 561 U.S. 247 (2010).

[2] United States v. Hoskins, 902 F.3d 69 (2d Cir. 2018). Although the Second Circuit rejected the government’s argument that Hoskins could be charged under the conspiracy and complicity statutes for conduct not otherwise reachable by the FCPA, id. at 97, he was nevertheless found guilty at trial in November 2019 on a different theory of liability: that he acted as the agent of Alstom S.A.’s American subsidiary. See Jody Godoy, Ex-Alstom Exec Found Guilty On 11 Counts In Bribery Trial, Law360 (Nov. 8, 2019), https://www.law360.com/articles/1218374/ex-alstom-exec-found-guilty-on-11-counts-in-bribery-trial.

[3] See, e.g., United States v. Elbaz, 332 F. Supp. 3d 960, 974 (D. Md. 2018) (collecting cases where extraterritorial conduct not subject to the wire fraud statute).

[4] Jed S. Rakoff, The Federal Mail Fraud Statute (Part I), 18 Duq. L. Rev. 771, 822 (1980).

[5] Many of the SUAs covered by Section 1956 are incorporated by cross-references to other statutes. See 18 U.S.C. § 1956(c)(7). All of the predicate acts under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, for instance, are SUAs under Section 1956. 18 U.S.C. § 1956(c)(7)(a). One commentator has estimated that there are “250 or so” predicate acts in Section 1956. Stefan D. Cassella, The Forfeiture of Property Involved in Money Laundering Offenses, 7 Buff. Crim. L. Rev. 583, 612 (2004). Another argues this estimate is “exceptionally conservative.” Charles Doyle, Cong. Research Serv., RL33315, Money Laundering: An Overview of 18 U.S.C. § 1956 and Related Federal Criminal Law 1 n.2 (2017).

[6] See, e.g., Fifth Circuit Pattern Jury Instructions (Criminal Cases) Nos. 2.76A, 2.76B, available at http://www.lb5.uscourts.gov/viewer/?/juryinstructions/Fifth/crim2015.pdf; Ninth Circuit Manual of Model Criminal Jury Instruction Nos. 8.147-49, available at http://www3.ce9.uscourts.gov/jury-instructions/sites/default/files/WPD/Criminal_Instructions_2019_12_0.pdf.

[7] 18 U.S.C. § 1956(f).

[8] 18 U.S.C. § 1956(c)(2).

[9] See, e.g., Fifth Circuit Pattern Jury Instructions (Criminal Cases) No. 2.77; Ninth Circuit Manual of Model Criminal Jury Instruction No. 8.150.

[10] Stefan D. Cassella, The Money Laundering Statutes (18 U.S.C. §§ 1956 and 1957), The United States Attorneys’ Bulletin, Vol. 55, No. 5 (Sept. 2007); see also 18 U.S.C. § 1956(c)(4)(i) (definition of “financial transaction”).

[11] United States v. Ulbricht, 31 F. Supp. 3d 540, 549-50 (S.D.N.Y. 2014).

[12] Id. at 568-69.

[13] Id. Ultimately, Ulbricht was convicted and his conviction was affirmed on appeal. See United States v. Ulbricht, 858 F.3d 71 (2d Cir. 2017). The Second Circuit did not address the district court’s interpretation of the term “financial transactions” under Section 1956.

[14] 18 U.S.C. § 1956(f)(1).

[15] International Monetary Fund, Recent Trends in Correspondent Banking Relationships: Further Considerations, at 9 (April 21, 2017), https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Policy-Papers/Issues/2017/04/21/recent-trends-in-correspondent-banking-relationships-further-considerations.

[16] Id.

[17] Bank for International Settlements Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures, Correspondent Banking, at 12 (July 2016), https://www.bis.org/cpmi/publ/d147.pdf.

[18] See generally Bill Browder, Red Notice: A True Story of High Finance, Murder, and One Man’s Fight for Justice (2015). The alleged scheme was discovered by Russian tax lawyer Sergei Magnitsky, who was arrested on specious charges and died after receiving inadequate medical treatment in a Russian prison. In response to Magnitsky’s death, the United States passed a bill named after him sanctioning Russia for human rights abuses. See Russia and Moldova Jackson–Vanik Repeal and Sergei Magnitsky Rule of Law Accountability Act of 2012, Pub. L. 112–208 (2012).

[19] Second Amended Complaint at 10-12, United States v. Prevezon Holdings Ltd., No. 13-cv-06326 (S.D.N.Y. Oct. 23, 2015), ECF No. 381.

[20] United States v. Prevezon Holdings Ltd., 251 F. Supp. 3d 684, 691-92 (S.D.N.Y. 2017).

[21] Id. at 692.

[22] Id. at 693.

[23] Id.

[24] Stewart Bishop, Boustani Acquitted in $2B Mozambique Loan Fraud Case, Law360 (Dec. 2, 2019), https://www.law360.com/articles/1221333/boustani-acquitted-in-2b-mozambique-loan-fraud-case.

[25] Superseding Indictment at 6, United States of America v. Boustani et al., No. 1:18-cr-00681 (E.D.N.Y. Aug. 16, 2019), ECF No. 137.

[26] Id. at 6-7.

[27] Id. at 33.

[28] Motion to Dismiss at 35-36, United States of America v. Boustani et al., No. 1:18-cr-00681 (E.D.N.Y. June 21, 2019), ECF No. 98.

[29] Id. at 36.

[30] Opposition to Motion to Dismiss at 38, United States of America v. Boustani et al., No. 1:18-cr-00681 (E.D.N.Y. July 22, 2019), ECF No. 113.

[31] Id. at 34-35 (citing United States v. All Assets Held at Bank Julius (“All Assets”), 251 F. Supp. 3d 82, 96 (D.D.C. 2017).)

[32] Decision & Order Denying Motions to Dismiss at 14, United States of America v. Boustani et al., No. 1:18-cr-00681 (E.D.N.Y. Oct. 3, 2019), ECF No. 231.

[33] Id. at 15-16; see also All Assets, 251 F. Supp. 3d at 95 (finding correspondent banking transactions fall within U.S. money laundering statutes because “[t]o conclude that the money laundering statute does not reach [Electronic Fund Transfers] simply because [defendant] himself did not choose a U.S. bank as the correspondent or intermediate bank for his wire transfers would frustrate Congress’s intent to prevent the use of U.S. financial institutions ‘as clearinghouses for criminals’”). In United States v. Firtash, No. 13-cr-515, 2019 WL 2568569 (N.D. Ill. June 21, 2019), the defendant recently moved to dismiss an indictment on grounds including that correspondent banking transactions do not fall within the scope of the U.S. money laundering statute. The court has sidestepped the argument for now, concluding that this argument “does not support dismissal of the Indictment at this stage” because “the Indictment does not specify that the government’s proof is limited to correspondent bank transactions.” Id. at *9.

[34] Stewart Bishop, Boustani Acquitted in $2B Mozambique Loan Fraud Case, Law360 (Dec. 2, 2019), https://www.law360.com/articles/1221333/boustani-acquitted-in-2b-mozambique-loan-fraud-case.

[35] Id.

[36] Id.

[37] Id.

[38] 18 U.S.C. § 1956(c)(7)(B)(iv). In United States v. Chi, 936 F.3d 888, 890 (9th Cir. 2019), the Ninth Circuit recently rejected the argument that the term “bribery of a public official” in Section 1956 should be read to mean bribery under the U.S. federal bribery statute, as opposed to the article of the South Korean Criminal Code at issue in that case.

[39] 18 U.S.C. § 1956(c)(7)(B)(iii).

[40] U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Attorney General Loretta E. Lynch Delivers Remarks at Press Conference Announcing Charges Against Nine FIFA Officials and Five Corporate Executives (May 27, 2015), https://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/attorney-general-loretta-e-lynch-delivers-remarks-press-conference-announcing-charges.

[41] Superseding Indictment at ¶¶ 95-360, United States v. Hawit, No. 15-cr-252 (E.D.N.Y. Nov. 25, 2015), ECF No. 102.

[42] See, e.g., id. at ¶¶ 30-93.

[43] See, e.g., id. at ¶ 371.

[44] Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, High-Ranking Soccer Officials Convicted in Multi-Million Dollar Bribery Schemes (Dec. 26, 2017), https://www.justice.gov/usao-edny/pr/high-ranking-soccer-officials-convicted-multi-million-dollar-bribery-schemes.

[45] U.S. Dep’t of Justice, FIFA Prosecution United States v. Napout et al. and Related Cases, Upcoming Court Dates, https://www.justice.gov/usao-edny/file/799016/download (last updated Nov. 5, 2019).

[46] Superseding Indictment, supra note 41, at ¶ 41.

[47] Superseding Indictment, supra note 41, at ¶¶ 376-81, 501-04.

[48] Memorandum of Law in Support of Defendant Juan Angel Napout’s Motion to Dismiss All Charges for Lack of Extraterritorial Jurisdiction, at 3-4, Hawit, supra note 41, ECF No. 491-1.

[49] United States v. Hawit, No. 15-cr-252, 2017 WL 663542, at *8 (E.D.N.Y. Feb. 17, 2017).

[50] United States v. Napout, 332 F. Supp. 3d 533, 547 (E.D.N.Y. 2018).

[51] Id. On appeal, Napout challenged the extraterritoriality of the honest-services wire-fraud statutes, a case currently pending before the Second Circuit. See United States of America v. Webb et al., No. 18-2750 (2d. Cir. appeal docketed Sept. 17, 2018), Dkt. 107. Marin did not raise the extraterritoriality of the money laundering statute on appeal. Id., Dkt. 104.

[52] Heather Chen, Mayuri Mei Lin, and Kevin Ponniah, 1MDB: The Playboys, PMs and Partygoers Around a Global Financial Scandal, BBC (Apr. 2, 2019), https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-46341603; see generally Tom Wright & Bradley Hope, Billion Dollar Whale: The Man Who Fooled Wall Street, Hollywood, and the World (2018).

[53] Complaint at 6, United States v.“The Wolf of Wall Street,” No. 2:16-cv-05362 (C.D. Cal. July 20, 2016), ECF No. 1, https://www.justice.gov/archives/opa/page/file/877166/download.

[54] Complaint, supra note 53, at 37.

[55] Najib 1MDB Trial: Malaysia Ex-PM Faces Court in Global Financial Scandal, BBC (Apr. 3, 2019), https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-47194656. In the aftermath of the scandal, Nazak was voted out of office and currently faces trial in Malaysia. Id.

[56] Complaint, supra note 53, at 63-65.

[57] Complaint, supra note 53; Rishi Iyengar, ‘Wolf of Wall Street’ Maker Settles US Lawsuit for $60 Million, CNN Business (Mar. 7, 2018), https://money.cnn.com/2018/03/07/media/wolf-wall-street-red-granite-1mdb-settlement/index.html.

[58] See Complaint, supra note 53, at 132.

[59] Consent Judgment of Forfeiture, No. 2:16-cv-05362 (C.D. Cal. Mar. 8, 2018), ECF No. 143. As a part of the settlement, Red Granite Pictures agreed to forfeit $60 million. Id. at 5.

[60] See United States v. Any Rights to Profits, Royalties and Distribution Proceeds Owned by or Owed Relating to EMI Music Publishing Group, Stipulation and Request to Enter Consent Judgment of Forfeiture, No. 16-cv-05364 (C.D. Cal. Oct. 30, 2019), ECF No. 180; Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, United States Reaches Settlement to Recover More Than $700 Million in Assets Allegedly Traceable to Corruption Involving Malaysian Sovereign Wealth Fund (Oct. 30, 2019), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/united-states-reaches-settlement-recover-more-700-million-assets-allegedly-traceable.

[61] See Indictment, United States v. De Leon-Perez et al., No. 4:17-cr-00514 (S.D. Tex. Aug. 23, 2017), ECF No. 1; Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Two Members of Billion-Dollar Venezuelan Money Laundering Scheme Arrested (July 25, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/two-members-billion-dollar-venezuelan-money-laundering-scheme-arrested.

[62] Criminal Information at 1-2, United States v. Krull, No. 1:18-cr-20682 (S.D. Fla. Aug. 16, 2018), ECF No. 23; Criminal Complaint at 6, United States v. Guruceaga, et al., No. 18-MJ-03119 (S.D. Fla. July 23, 2018), ECF No. 3.

[63] Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Former Venezuelan Official Pleads Guilty to Money Laundering Charge in Connection with Bribery Scheme (July 16, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/former-venezuelan-official-pleads-guilty-money-laundering-charge-connection-bribery-scheme-0.

[64] See Defendant’s Motion to Dismiss at 9-24, United States v. Villalobos, No. 4:17-cr-00514 (S.D. Tex. Mar. 28, 2019), ECF No. 123.

[65] See id. at 21-35.

[66] Gina Chon & Ben McLannahan, Banks face US investigation in Fifa corruption scandal, Financial Times (May 27, 2015); see also Christie Smythe & Keri Geiger, U.S. Probes Bank Links in FIFA Marketing Corruption Scandal, Bloomberg (May 27, 2015).

[67] Christopher M. Matthews & Rachel Louise Ensign, U.S. Authorities Probe Banks’ Handling of FIFA Funds, Wall St. Journal (July 23, 2015).

[68] Fed. Ins. Co. v. United States, 882 F.3d 348, 368 (2d Cir. 2018).

[69] See, e.g., Global-Tech Appliances, Inc. v. SEB S.A., 563 U.S. 754, 769 (2011); United States v. Florez, 368 F.3d 1042, 1044 (8th Cir. 2004).

[70] Philip A. Lacovara & David P. Nicoli, Vicarious Criminal Liability of Organizations: RICO as an Example of a Flawed Principle in Practice, 64 St. John’s L. Rev. 725, 725-26 (1990).

[71] See U.S. Department of Justice, Principles of Federal Prosecution of Business Organizations (Aug. 28, 2008), https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/dag/legacy/2008/11/03/dag-memo-08282008.pdf.

The following Gibson Dunn attorneys assisted in preparing this client update: M. Kendall Day, Stephanie L. Brooker, F. Joseph Warin, Chris Jones, Jaclyn Neely, Chantalle Carles Schropp, Alexander Moss, Jillian Katterhagen Mills, Tory Roberts, and summer associates Beatrix Lu and Olivia Brown.

Gibson Dunn has deep experience with issues relating to the defense of financial institutions. For assistance navigating white collar or regulatory enforcement issues involving financial institutions, please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, any of the leaders and members of the firm’s Financial Institutions, White Collar Defense and Investigations, or International Trade practice groups, or the following authors in the firm’s Washington, D.C., New York, and San Francisco offices:

M. Kendall Day – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-955-8220, [email protected])

Stephanie Brooker – Washington, D.C.(+1 202-887-3502, [email protected])

F. Joseph Warin – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3609, [email protected])

Jaclyn Neely – New York (+1 212-351-2692, [email protected])

Chris Jones* – San Francisco (+1 415-393-8320, [email protected])

Chantalle Carles Schropp – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-955-8275, [email protected])

Alexander R. Moss – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3615, [email protected])

Jillian N. Katterhagen* – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-955-8283 , [email protected])

Please also feel free to contact any of the following practice group leaders:

Financial Institutions Group:

Matthew L. Biben – New York (+1 212-351-6300, [email protected])

Stephanie Brooker – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3502, [email protected])

Arthur S. Long – New York (+1 212-351-2426, [email protected])

White Collar Defense and Investigations Group:

Joel M. Cohen – New York (+1 212-351-2664, [email protected])

Charles J. Stevens – San Francisco (+1 415-393-8391, [email protected])

F. Joseph Warin – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3609, [email protected])

International Trade Group:

Ronald Kirk – Dallas (+1 214-698-3295, [email protected])

Judith Alison Lee – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3591, [email protected])

*Mr. Jones and Ms. Katterhagen Mills are not yet admitted in California and Washington, D.C., respectively. They are practicing under the supervision of Principals of the Firm.

© 2020 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP

Attorney Advertising: The enclosed materials have been prepared for general informational purposes only and are not intended as legal advice.