International Trade 2024 Year-End Update

Client Alert | February 6, 2025

The four years of the Biden administration were marked by the most aggressive and far-reaching use of international trade tools of any U.S. administration in history. Its final acts—some just days before the new administration took power—were among the most impactful of these measures. While there remains uncertainty about the Trump administration’s trade policy, early indications are that the Trump team will wield these tools in an even more aggressive manner focused on an ever-larger set of policy goals—with unknown effects, both at home and abroad.

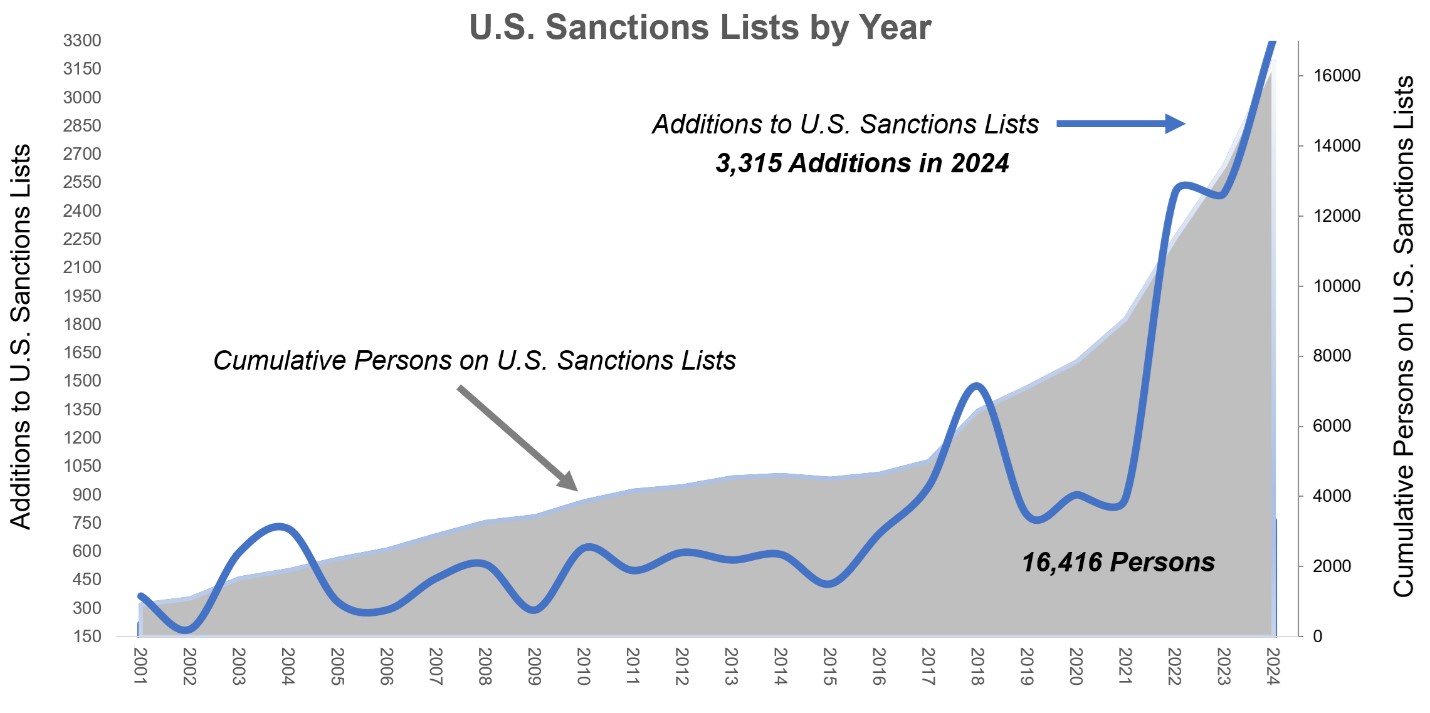

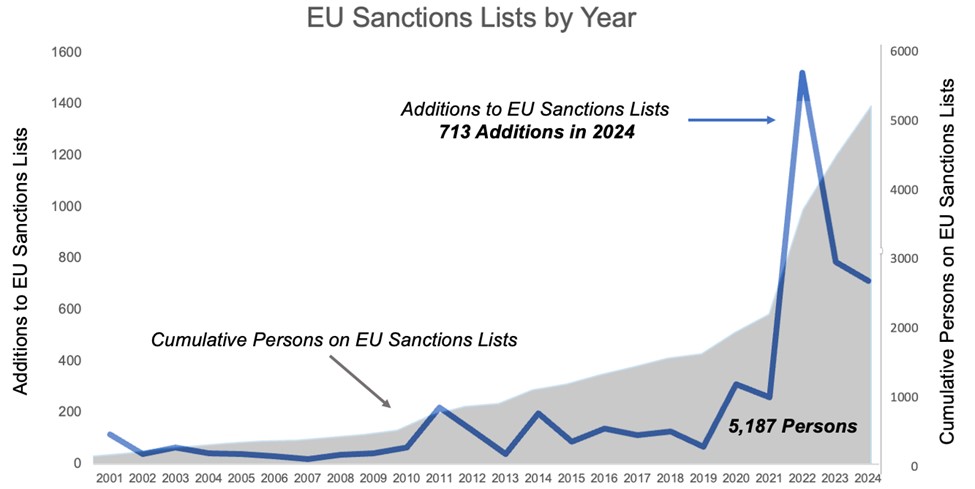

Throughout 2024, the United States, the European Union, and the United Kingdom continued their fast-paced adoption and usage of the entire suite of international trade tools to exert pressure on Moscow, Beijing, and other targets. As but one indicator of his preference for the use of these tools, President Biden during his tenure imposed sanctions at a faster rate than any of his predecessors by adding thousands of names per year to restricted party lists maintained by the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (“OFAC”). That upswing accelerated in 2024 as the United States added a record-shattering number of, predominantly Russian, individuals and entities to OFAC sanctions lists:

|

Sanctions designations, however, tell only a small part of the story. Policymakers in Washington, London, and other capitals this past year also unveiled groundbreaking export controls, and focused on novel outbound investment regimes, in a bid to slow China’s advances in certain critical technologies like semiconductors and artificial intelligence (“AI”).

Following a wave of turnover in the White House, Downing Street, the EU institutions, and in other halls of power, the world’s major economies appear poised to continue their heavy reliance on trade controls—though the mix of tools and targets could radically shift. Under President Trump, the United States appears set to favor aggressive threats and uses of tariffs (over other tools in the international trade arsenal), and, as we have already seen, may wield trade restrictive measures against both strategic competitors and core partners like Canada, Mexico, and the European Union. Other jurisdictions in Europe, Asia, and the Americas are likely to deploy those same tools, either in retaliation against U.S. measures or in pursuit of their own strategic interests. After several years of closely coordinated measures in support of common objectives such as impeding Russia’s war in Ukraine, we anticipate a reshaped international trade landscape marked by friction among traditional allies and heightened uncertainty for the business community.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

A. Russia

B. Iran

C. Syria

D. Venezuela

E. Cuba

F. Crypto/Virtual Currencies

G. OFAC Enforcement Trends

A. China

B. Russia and Belarus

C. Multilateral Controls

D. End-Use and End-User Controls

E. Compliance Expectations

F. Voluntary Self-Disclosures

G. BIS Enforcement Trends

III. U.S. Foreign Investment Restrictions

A. Sanctions

B. Export Controls

C. Foreign Investment Restrictions

A. Sanctions

B. Export Controls

C. Foreign Investment Restrictions

Following the Kremlin’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in early 2022, the United States, in close coordination with its allies and partners, unleashed a historic barrage of trade restrictions on Russia. As the war in Ukraine stretched into a third year, the Biden administration in 2024 continued its shift from rapidly introducing new and often novel trade controls to incrementally expanding existing measures such as blocking sanctions, services prohibitions, import bans, and secondary sanctions. Such seemingly disparate measures were each calculated to deny Russia the capital and materiel needed to wage war in Ukraine.

Notably, President Biden during his final months in the White House sharply increased sanctions on Russia’s financial and energy sectors, including blacklisting major Russian banks and oil companies. Those actions, which aimed to restrict Moscow’s access to the international financial system and limit its chief source of hard currency, also potentially increase his successor’s leverage at the negotiating table. After his campaign trail vow to end the war in Ukraine on his first day in office failed to materialize, President Trump now at least appears poised to potentially further escalate sanctions and other trade measures in a bid to pressure the Kremlin (and Kyiv) into seeking a negotiated resolution to the conflict. Depending upon how events unfold, such U.S. measures could potentially include hiking tariffs on imported Russian goods, targeting additional oil producers, and wielding secondary sanctions against foreign banks that continue to engage with Russia. It is also likely that the Trump administration will seek to bring other, seemingly unrelated, issues—such as securing U.S. access to critical minerals—into any deal.

1. Blocking Sanctions

Since February 2022, the United States, in an unprecedented burst of activity, has added thousands of new Russia-related individuals and entities to OFAC sanctions lists. That trend intensified during the final year of the Biden administration as the United States, on eight separate occasions, added 100 or more new Russia–related targets to OFAC’s Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons (“SDN”) List—an extraordinary pace considering that around 13,000 parties had been added to the SDN List over the preceding twenty years combined.

Blocking sanctions are arguably the most potent tool in a country’s sanctions arsenal, especially for countries such as the United States with an outsized role in the global financial system. Upon becoming designated an SDN (or other type of blocked person), the targeted individual or entity’s property and interests in property that come within U.S. jurisdiction are blocked (i.e., frozen) and U.S. persons are, except as authorized by OFAC, generally prohibited from engaging in transactions involving the blocked person. The SDN List therefore functions as the United States’ principal sanctions-related restricted party list. Moreover, the effects of blocking sanctions often reach beyond the parties identified by name on the list. By operation of OFAC’s Fifty Percent Rule, restrictions generally also extend to entities owned 50 percent or more in the aggregate by one or more blocked persons, whether or not the entity itself has been explicitly identified.

During 2024 and continuing into early 2025, the United States repeatedly used its targeting authorities to block Russian business elites, as well as substantial enterprises operating in sectors such as banking, energy, and technology seen as critical to financing and sustaining the Kremlin’s war effort. Notable designations included:

- Oligarchs such as the chief executive officers of several major Russian oil companies;

- Financial institutions, including Gazprombank, the Moscow Exchange, Russia’s National Settlement Depository, and dozens of Russian securities registrars, further severing Russia’s access to the international financial system;

- Energy firms such as Gazprom Neft and Surgutneftegas, which were targeted to limit Russia’s current energy revenues and future extractive capabilities;

- Shipping companies such as Sovcomflot and Rosneftflot, to impede the transport of Russian-origin petroleum and petroleum products to overseas buyers;

- Military-industrial firms, including hundreds of companies operating in the technology, defense and related materiel, construction, aerospace, and manufacturing sectors of Russia’s economy; and

- Third-country facilitators of sanctions and export control evasion, including shipping companies and vessels alleged to have violated the price cap on Russian crude oil and petroleum products, plus hundreds of parties located in major transshipment hubs such as Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, and the People’s Republic of China (“PRC”).

Substantially all of the parties described above were designated pursuant to Executive Order (“E.O.”) 14024, as amended, a measure that President Biden signed at the outset of his term that authorizes blocking sanctions against persons determined to operate or have operated in certain sectors of the Russian Federation economy identified by the U.S. Secretary of the Treasury. Throughout President Biden’s tenure, OFAC relied almost exclusively on E.O. 14024 to target new Russia-related parties. However, during its final days in office, the administration broadened its use of blocking sanctions in two novel respects.

The Biden administration in January 2025 added a further sanctions basis to over 100 Russian parties by re-designating key targets—including major oil companies, shippers, manufacturers, and banks—pursuant to an earlier Obama-era authority, Executive Order 13662. Sanctions on those entities under E.O. 14024 remained in place. Although imposing blocking sanctions under additional authorities did not result in those targets becoming subject to further restrictions, the use of E.O. 13662 raises the procedural bar for easing sanctions on such persons by triggering a unique congressional review mechanism in the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (“CAATSA”). Consequently, the Trump administration is now obliged to submit a detailed report to Congress and, absent congressional action, wait a specified number of days before lifting sanctions on any parties that have been designated under E.O. 13662—which appears calculated to delay, and increase the domestic political costs of, a possible future effort by President Trump to relax sanctions on Russia.

Concurrent with that announcement, the Biden administration further expanded the potential bases upon which parties can become designated for engaging with Russia. Building upon the various sectors that had been identified in prior years, the Biden administration in January 2025 authorized the imposition of blocking sanctions on parties that operate in Russia’s energy sector, which OFAC broadly defines to include upstream, midstream, and downstream activities related to oil, natural gas, and other products capable of producing or transporting energy. Crucially, OFAC has indicated that parties operating in targeted sectors are not automatically sanctioned, but rather risk becoming sanctioned if they are determined by the Secretary of the Treasury to have engaged in targeted activities. That said, after years of treading lightly around Russian oil and gas producers to avoid roiling global markets, the Biden administration in its final weeks appears to have been emboldened by more stable energy supplies to sharply restrict dealings involving Russia’s extractive industries. Notwithstanding the considerable policy differences between the two administrations, President Trump, at least in the near term, appears likely to maintain and potentially expand U.S. sanctions on Russian energy to maximize U.S. leverage in future negotiations with Moscow.

2. Services Prohibitions

Since the opening months of the war in Ukraine, the United States has supplemented its use of blocking sanctions against targeted individuals and entities by banning U.S. persons from exporting to Russia certain professional, technical, and financial services—especially including services used to bring Russian energy to market.

Executive Order 14071 prohibits the exportation from the United States, or by a U.S. person, of any category of services as may be determined by the Secretary of the Treasury, to any person located in the Russian Federation. Acting pursuant to that broad and flexible legal authority, the United States during the first two years of the war barred U.S. exports to Russia of certain categories of services that, if misused, could enable sanctions evasion, bolster the Russian military, and/or contribute to Russian energy revenues.

In April 2024, the United States expanded upon those earlier prohibitions by barring the exportation to Russia of certain services related to the acquisition of Russian-origin aluminum, copper, or nickel to limit the trading of Russian metals on global exchanges. In June 2024, OFAC, in close coordination with the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security (“BIS”), restricted exports to Russia of information technology (“IT”) consultancy and design services, as well as IT support services and cloud-based services for certain types of widely used business software, to prevent U.S. technical expertise and Software as a Service (“SaaS”) offerings from being leveraged by Russia’s military-industrial base.

In conjunction with the imposition of blocking sanctions against several major Russian oil companies (discussed above), the Biden administration in January 2025 further limited U.S. person activities by, effective February 27, 2025, prohibiting the exportation to Russia of petroleum services, which OFAC defines in expansive terms to include “services related to the exploration, drilling, well completion, production, refining, processing, storage, maintenance, transportation, purchase, acquisition, testing, inspection, transfer, sale, trade, distribution, or marketing of petroleum, including crude oil and petroleum products.” As such, absent an exclusion—such as for services related to the maritime transport of Russian crude oil or petroleum products purchased at or below a specified price cap—or authorization from OFAC in the form of a license, U.S. persons starting in late February potentially risk U.S. sanctions exposure for providing services that enable Russia to exploit its hydrocarbon resources.

3. Import Prohibitions

Consistent with a whole-of-government approach to limiting Russian revenue, the United States during 2024 continued to expand prohibitions on the importation of certain Russian-origin goods—principally consisting of items closely associated with Russia or that otherwise have the potential to generate hard currency for the Kremlin.

In prior years, the Biden administration used this particular policy tool to bar imports into the United States of certain energy products of Russian Federation origin, fish, seafood, alcoholic beverages, non-industrial diamonds, and gold. As with other Russia-related sanctions authorities, the Secretary of the Treasury has broad discretion under Executive Order 14068, as amended, to, at some later date, extend the U.S. import ban to additional Russian-origin goods. The Biden administration during the past year wielded that authority to prohibit the importation into the United States of additional Russian commodities, including additional categories of diamonds and diamond jewelry, as well as aluminum, copper, and nickel.

Highlighting the degree of bipartisan support for limiting Russia’s access to the U.S. market, the U.S. Congress in May 2024 enacted legislation barring the importation into the United States of Russian-origin low-enriched uranium.

Although most other imports of Russian-origin items remain permissible under U.S. law, bilateral trade in goods between the United States and Russia plunged to a 30-year low in 2024 and appears unlikely to rebound absent a sea change in relations between Washington and Moscow. As it has been since the start of the 2022 invasion, the implications of trade restrictions will be felt much more by countries in Europe and Asia that have far more robust trading relationships with Moscow.

4. Secondary Sanctions

As part of a broader effort to limit sanctions and export control evasion, the United States in late 2023 authorized secondary sanctions on foreign financial institutions that, knowingly or unknowingly, facilitate significant transactions involving Russia’s military-industrial base. As we observe in a prior client alert, these restrictive measures are noteworthy not simply because they create new secondary sanctions risks for foreign banks and other financial institutions, but also because they expose these financial institutions to such risks based on the facilitation of their customers’ trade in certain enumerated goods, and do so under a standard of strict liability (i.e., without requiring any intent or even having knowledge of the activity).

This is a meaningful departure from historical practice. Under certain U.S. sanctions programs—namely, those targeting Iran, North Korea, Russia, Syria, Hong Kong, and terrorism—persons outside of U.S. jurisdiction that engage in enumerated transactions with certain targeted persons or sectors, including transactions with no ostensible U.S. nexus, risk becoming subject to U.S. secondary sanctions. Such measures target certain significant transactions involving, for example, Iranian port operators, shipping, and shipbuilding. In practice, secondary sanctions are highly discretionary in nature and principally designed to prevent non-U.S. persons from engaging in certain specified transactions that are prohibited to U.S. persons. If OFAC determines that a non-U.S. person has engaged in such transactions, the agency may impose punitive measures on the non-U.S. person which vary from the potentially relatively innocuous (e.g., blocking their use of the U.S. Export-Import Bank) to the severe (e.g., blocking use of the U.S. financial system or blocking all property interests—essentially adding them to the SDN List). Until December 2023, non-U.S. persons only potentially risked secondary sanctions exposure, under the small handful of sanctions programs that include such measures, for knowingly engaging in certain significant transactions.

The Biden administration in December 2023 issued Executive Order 14114 authorizing OFAC to impose secondary sanctions on foreign financial institutions that are deemed to have:

- Conducted or facilitated a significant transaction involving a person that has been blocked for operating in certain sectors of Russia’s economy (such persons, “Covered Persons”); or

- Conducted or facilitated a significant transaction, or provided any service, involving Russia’s military-industrial base, including the direct or indirect sale, supply, or transfer to Russia of specified items such as certain machine tools, semiconductor manufacturing equipment, electronic test equipment, propellants and their precursors, lubricants and lubricant additives, bearings, advanced optical systems, and navigation instruments (such items, “Covered Items“).

Upon a determination by the Secretary of the Treasury that a foreign financial institution has engaged in one or more of the sanctionable transactions described above, OFAC can (1) impose full blocking measures on the institution or (2) prohibit the opening of, or prohibit or impose strict conditions on the maintenance of, correspondent accounts or payable-through accounts in the United States. Such measures are a powerful deterrent to engaging in dealings involving Covered Persons or Covered Items, as the potential consequence of such a transaction (i.e., imposition of blocking sanctions or loss of access to the U.S. financial system) is tantamount to a death sentence for a globally connected bank.

In June 2024, in recognition of Russia’s transition to a wartime economy, the United States broadened the reach of U.S. secondary sanctions by publishing updated guidance that expands OFAC’s interpretation of “Russia’s military-industrial base” to include not only persons that have been blocked for operating in certain sectors of Russia’s economy—formerly, the technology, defense and related materiel, construction, aerospace, or manufacturing sectors—but all persons blocked pursuant to Executive Order 14024. As a practical matter, that shift both simplifies compliance for foreign financial institutions by eliminating the need to assess whether a transaction party is among a subset of Russian SDNs that can give rise to secondary sanctions exposure, and enhances the deterrent effect of U.S. sanctions by expanding the universe of Russia-related transactions that can place a foreign bank at risk of losing access to the U.S. financial system.

Notably, the Biden administration invoked that secondary sanctions authority for the first time in January 2025 by imposing blocking sanctions on a Kyrgyzstan-based bank for allegedly processing payments on behalf of a blocked Russian bank with close ties to Russia’s defense industry. Although the use of U.S. secondary sanctions against banks that continue to engage with Russia is so far limited and isolated, to the extent President Trump is inclined to escalate pressure on Moscow, that designation could offer the new administration a model for targeting progressively larger foreign financial institutions that continue to process Russia-related trade.

5. Prospects for Further Sanctions on Russia

As President Trump looks to deliver on his oft-repeated campaign pledge to end the war in Ukraine, the United States could soon further tighten trade restrictions in an attempt to push Moscow to the negotiating table. Options available to the Trump administration under such an approach include increasing tariffs on the limited volume of Russian goods still imported into the United States or, more consequentially, targeting Russia’s crucial financial and energy sectors by imposing blocking sanctions on all remaining Russia-based banks and oil majors Rosneft and Lukoil. It is also conceivable that the new administration could, in a bid to constrict Moscow’s oil revenues, threaten to impose secondary sanctions on foreign financial institutions (including especially in China and India) that continue to process payments involving Russian petroleum and petroleum products.

Conversely, if eventual talks among Washington, Moscow, and Kyiv show signs of progress, it would not be surprising if the White House just as quickly eases restrictions on dealings involving Russia. With the exception of the E.O. 13662 re-designations noted above, nearly all of the Biden-era measures targeting Russia (which were implemented via Executive Order) can be—as President Trump demonstrated in his first days in office—rescinded with the stroke of a pen. For example, President Trump could narrow or revoke existing measures such as the prohibition on “new investment” in the Russian Federation set forth in E.O. 14071 by issuing new or amended Executive Orders, or by issuing permissive general licenses. Any such relaxation of U.S. sanctions could, however, result in a split between the United States and its European allies and partners, who to date have shown little appetite for easing their own considerable restrictions on Russia.

President Trump’s return to power also casts into doubt an unprecedented effort to leverage Russia’s sovereign assets to fund Ukraine’s defense and reconstruction. As the cost of the war continued to mount, the United States and its partners during 2024 explored a range of options to deploy the nearly $300 billion in Russian central bank reserves, principally held in Europe, that the allies immobilized in the opening weeks of the conflict. At a June 2024 summit, the Group of Seven (“G7”) ultimately agreed on a novel mechanism whereby the allies would extend $50 billion in loans to Ukraine, to be paid down over time by the interest that is continuing to accrue on the Kremlin’s assets held abroad. That U.S.-led initiative—dubbed the Extraordinary Revenue Acceleration Loan program—resulted in the United States disbursing a $20 billion loan to Kyiv in December 2024, with a separate €3 billion loan from the European Commission following in January 2025. While stopping short, at least so far, of seizing Russian state property, the loan program nevertheless has potentially fundamental consequences for global finance, which heretofore held a nearly unshakable belief in the immunity of sovereign assets—especially of major states.

Iran suffered a series of strategic setbacks in 2024, including a deepening economic crisis, multiple rounds of Israeli airstrikes, the decimation of Hamas and Hezbollah’s senior leadership, and the collapse of the Assad regime in Syria. Following President Trump’s return to the White House, Tehran could soon be forced to decide whether to pursue negotiations aimed at securing sanctions relief, or race for a nuclear weapon to restore the Islamic Republic’s battered deterrence.

As these developments unfolded, the Biden administration during 2024 continued to aggressively use its sanctions authorities to add individuals and entities complicit in Iran’s destabilizing activities to the SDN List. Frequent targets of Iran-related designations included Iranian government officials, entities involved in unmanned aerial vehicle (“UAV”) and ballistic missile procurement, and entities and vessels involved in the Iranian petroleum and petrochemicals trade.

The pace of Iran sanctions designations could further increase under President Trump as part of the resumption of his first term’s “maximum pressure” economic campaign, which he announced on February 4, 2025. That effort aims to deny Tehran the resources needed to fund its terrorist proxies. An accompanying national security memorandum previewed the Trump administration’s likely targeting of third-country shipping companies, insurers, and port operators that enable Iranian oil exports. If need be, the pressure campaign could potentially invoke legislation enacted in April 2024, including the Stop Harboring Iranian Petroleum Act and the Iran-China Energy Sanctions Act of 2023, that authorizes the President to impose sanctions on non-U.S. persons, including especially in China, that are involved in bringing Iranian oil to market.

U.S. sanctions on Syria were largely quiet for much of the past year, until the sudden December 8, 2024 ouster of Syria’s longtime ruler Bashar al-Assad following a brutal, decade-long civil war. Despite the Assad regime’s collapse, Syria—alongside a small handful of other jurisdictions, presently including Cuba, Iran, North Korea, and certain Russian-occupied regions of Ukraine—remains subject to comprehensive U.S. sanctions, as a result of which U.S. persons are generally prohibited from engaging in transactions involving that country. Further complicating efforts to stabilize Syria and rebuild its shattered economy, the rebel group that in December 2024 became the country’s de facto governing authority, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (“HTS”), and its leader Ahmed Hussein al-Sharaa (formerly known by the nom de guerre Abu Mohammed al-Jawlani), each remain subject to U.S. blocking sanctions for their historical ties to the Islamic State and al Qaeda.

In January 2025, the United States announced a narrow and time-limited suspension of certain U.S. restrictions to “ensure that sanctions do not impede essential services and continuity of governance functions across Syria, including the provision of electricity, energy, water, and sanitation.” In particular, OFAC issued a general license that authorizes U.S. persons, until July 7, 2025, to engage in certain transactions involving: (1) Syria’s post-Assad governing institutions; (2) the sale, supply, storage, or donation of energy, including petroleum, petroleum products, natural gas, and electricity, to or within Syria; and (3) processing the transfer of noncommercial, personal remittances to Syria, including through the Central Bank of Syria. The authorizations set forth in that license exclude, among other things, any transactions involving military or intelligence entities or new investment in Syria by U.S. persons. Notably, the license authorizes financial transfers to blocked persons such as HTS for specified purposes such as effecting the payment to governing institutions in Syria of taxes, fees, or import duties—suggesting a U.S. policy interest in enabling the continuing functioning of the Syrian state, notwithstanding HTS and al-Sharaa’s status as designated terrorists.

Both the Biden and Trump administrations appear to have otherwise adopted a wait-and-see approach to Syria sanctions relief, with the further easing of U.S. restrictions likely contingent upon HTS demonstrating tangible progress toward forming an inclusive transitional government, protecting the rights of ethnic and religious minorities, pledging not to serve as a conduit for the export of Iranian destabilization, and responsibly disposing of Syria’s chemical weapons. In light of President Trump’s aggressive use of U.S. counterterrorism sanctions authorities during his first week in office—including to target drug cartels and the Yemen-based Houthis—the United States seems unlikely to lift blocking sanctions on HTS and its leader Ahmed Hussein al-Sharaa, at least in the near future.

The United States in early 2024 withdrew two short-lived forms of sanctions relief after Venezuela’s President Nicolás Maduro failed to uphold his commitments to take concrete steps toward holding free and fair elections.

As we describe in a prior client alert, the Biden administration in October 2023 announced a significant relaxation of U.S. sanctions on Venezuela in an attempt to incentivize the Maduro regime to take concrete steps toward the restoration of Venezuelan democracy. When the regime failed to uphold its end of the bargain, including by refusing to lift a ban on a leading presidential candidate holding public office, the U.S. Government in January 2024 quickly revoked a general license that had authorized U.S. nexus transactions involving Venezuela’s state-owned gold mining company—and warned that, absent a change in behavior by the Maduro regime, a separate general license authorizing most dealings involving the country’s oil or gas sector would meet a similar fate. A further tightening of U.S. sanctions followed in April 2024 when the Biden administration made good on that threat and allowed Venezuela General License 44 to expire—with the result that, unless separately authorized by OFAC, U.S. persons are again generally prohibited from engaging in transactions involving the state-owned oil giant Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (“PdVSA”).

Following a July 2024 presidential contest marred by widespread irregularities, the United States recognized opposition candidate Edmundo González as the country’s president-elect—to little effect, as Maduro clung to power and was sworn in for a third term in January 2025.

While democratization efforts have historically been the guide by which prior administrations have assessed the need for sanctions on Caracas, under the new Trump administration it appears that willingness to stem illegal immigration may serve as a favored guide in this regard. Indeed, we assess that if there is a Washington-Caracas deal to stem the flow of Venezuelan migrants northward, the United States under President Trump and Secretary of State Marco Rubio could opt to institute some easing of measures. January 2025 meetings between the Trump administration’s envoy for special missions Richard Grenell and the Maduro government resulted in Venezuela’s release of several U.S. prisoners, suggesting that a deal may be sought. However, in the absence of such a deal, we assess it as likely that we will see a further tightening of sanctions on the Maduro regime, including a potential narrowing or revocation of existing authorizations to engage with Venezuela’s crucial oil sector or a resumption of President Trump’s first-term practice of aggressively designating shipping companies and vessels that bring Venezuelan oil to market.

During 2024, U.S. sanctions on Cuba continued their decades-long trend of swinging sharply back and forth, depending upon whether Republicans or Democrats control the White House. During his waning months in power, President Biden modestly eased restrictions on Havana, including by authorizing U.S. banks to process certain Cuba-related payments and de-listing Cuba as a State Sponsor of Terrorism. However, that relief was short-lived, as President Trump unwound many of those same measures within hours of returning to the Oval Office.

Under the first Trump administration, the United States in 2019 prohibited U.S. banks from processing so‐called “U‐turn” payments. These transactions—which involve Cuban interests and originate from, and terminate, outside of the United States—enable Cuban entities doing business with non‐U.S. firms to access U.S. correspondent and intermediary banks and therefore to participate in U.S. Dollar‐denominated global trade. In May 2024, as part of a package of incremental changes to the Cuba regulations, the Biden administration issued a general license authorizing U.S. banks to again process such Cuba-related payments, provided that neither the originator nor the beneficiary, nor their respective banking institution, is a person subject to U.S. jurisdiction. From a policy perspective, the Biden administration appears to have been aiming to increase independent Cuban entrepreneurs’ access to the international financial system.

In a more sweeping—though, it turned out, temporary—reversal of Trump-era policy, President Biden on January 14, 2025 announced a Vatican-brokered agreement to secure the release of hundreds of Cuban political prisoners. In exchange, the United States rescinded Cuba’s designation as a State Sponsor of Terrorism, suspended a private right of action that had enabled lawsuits in U.S. courts against individuals and companies accused of “trafficking” in property confiscated by the Cuban government, and revoked a memorandum that underpins the U.S. ban on direct financial transactions involving certain entities identified on the State Department’s Cuba Restricted List. Reflecting the ongoing tug-of-war over Cuba policy, President Trump less than a week later rescinded each of those measures on his first day in office. As such, U.S. sanctions on Cuba are now, with modest exceptions, substantially similar to the restrictions that were in place when President Trump left office in 2021. To the extent President Trump and Secretary Rubio are inclined to further increase sanctions on Cuba, it is possible that the new administration could in coming months eliminate the authorization for “U-turn” payments, as well.

OFAC throughout the past several years has closely focused on illicit finance in the virtual currency sector, including through a mix of new sanctions designations and aggressive enforcement actions. However, a recent court decision finding that OFAC lacks authority to impose sanctions on immutable smart contracts, coupled with the Trump administration’s promises of lighter-touch regulation of the industry, could portend a shift in OFAC’s priorities away from digital assets and toward other sectors of the economy such as traditional finance.

In August and November 2022, OFAC imposed blocking sanctions on the virtual currency mixer Tornado Cash. Virtual currency mixers, as the name suggests, operate by mixing together funds deposited by many users before transmitting the funds to their individual recipients, thereby obfuscating the parties to a transaction. That designation represented a novel use of U.S. sanctions as, unlike a centralized platform in which a single company processes virtual currency transactions, Tornado Cash’s decentralized, smart contract model is essentially operated by self-executing code running on public blockchains without the need for human intervention. Tornado Cash users soon filed suit, arguing that there is no “person” or “property” for OFAC to sanction.

In November 2024, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, in a still-rare successful court challenge to a U.S. sanctions determination, held that OFAC exceeded its authority when it designated Tornado Cash’s immutable smart contracts (i.e., unalterable, open-source, privacy-enabling software code) as blockable property. In particular, the Fifth Circuit in Van Loon v. U.S. Department of the Treasury reasoned that, to constitute “property,” something must be “capable of being owned,” which in turn requires that an owner be capable of exercising “dominion” over it. The Court concluded that immutable smart contracts are unownable and therefore not “property” because they cannot be altered nor can anyone be excluded from using them. The Van Loon decision is noteworthy as it adds to a growing body of jurisprudence (discussed further below) limiting the authority of administrative agencies and, absent intervention by Congress, could complicate OFAC’s ability to restrict dealings involving digital assets going forward. We expect more challenges to OFAC actions in the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court’s June 2024 decision in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo (discussed below), which eliminated the requirement that courts defer to agencies’ reasonable interpretations of the statutes that they administer, and on which the Van Loon Court relied in reaching its conclusion.

In contrast with the Biden administration’s aggressive regulatory approach to the virtual currency sector, a second Trump administration seems likely to usher in a more permissive regulatory environment. Underscoring the White House’s expected posture toward the virtual currency industry, President Trump shortly before taking office launched his own digital token and, once in the White House, quickly issued an Executive Order directing an overhaul of U.S. digital assets policy. Following several years of robust U.S. sanctions enforcement against virtual currency industry participants, it is possible that OFAC could in coming months recalibrate its enforcement approach to once again prioritize other sectors.

1. Enforcement Actions and Compliance Lessons

During 2024, the combined amount of civil monetary penalties imposed by OFAC fell back in line with the agency’s long-term average after hitting a record-shattering $1.5 billion the year prior. That decline was principally driven by the absence of any blockbuster, nine-figure settlements. Across 12 enforcement actions resulting in monetary penalties, OFAC in 2024 levied an aggregate of $48.8 million in fines—an amount roughly on par with 2022 ($42.6 million) and modestly higher than 2021 or 2020 (both around $20 million). The two largest resolutions this past year involved monetary penalties of $20 million and $14.5 million, both stemming from alleged violations of U.S. sanctions on Iran. While enforcement actions are often a trailing indicator of OFAC enforcement priorities (given that matters can take several years to resolve after a violation has been found), this trend nonetheless suggests that dealings involving the Islamic Republic are likely to remain an area of continued focus for U.S. authorities during the months ahead.

We highlight below the most noteworthy compliance lessons from OFAC’s 2024 enforcement actions, many of which are thematically consistent with prior years. Some of these takeaways were explicitly communicated by OFAC through the “compliance considerations” section included in the web notice for each of its enforcement actions:

- Dealings in and around Iran can present heightened risks: Half of OFAC’s 12 cases announced during 2024 involved apparent Iran sanctions violations and highlight the importance (and expectation) of effective due diligence. OFAC, for example, suggested in a November 2024 settlement that companies’ due diligence efforts should take into account that sanctioned Iranian parties might not necessarily appear by name on the SDN List and may often be based in nearby jurisdictions such as the United Arab Emirates. The Trump administration’s February 2025 resumption of the Iran “maximum pressure” campaign explicitly ordered the expansion of enforcement efforts.

- Non-U.S. companies should ensure that their activities do not “cause” U.S. persons to violate U.S. sanctions restrictions: Five non-U.S. companies were penalized this past year for “causing” a U.S. person (such as a U.S. correspondent bank) to violate their own sanctions compliance obligations—a common fact pattern in recent years. OFAC has long maintained that non-U.S. companies are on notice of this obligation when they avail themselves of U.S. customers, goods, technology, or services. Non-U.S. companies should therefore be mindful that, even in cases in which an undertaking on its face has no readily discernable U.S. touchpoint, they must comply with U.S. sanctions when engaging in a transaction that involves even a fleeting U.S. touchpoint such as clearing a U.S. Dollar-denominated payment through a U.S. financial institution.

- U.S. parent companies should take steps to ensure that their non-U.S. subsidiaries comply with applicable sanctions restrictions: OFAC has repeatedly recommended that multinational enterprises assess the sanctions risks of their foreign subsidiaries, particularly those operating in high-risk jurisdictions. The agency has cautioned against pursuing new business overseas without implementing and maintaining proper compliance controls, such as policies for U.S. person directors, officers, and employees to recuse themselves from prohibited activities and whistleblower mechanisms to identify prohibited conduct.

- Companies should remain vigilant for efforts by persons in Russia and Russian-occupied regions of Ukraine to evade sanctions: Two of OFAC’s 12 published cases this past year alleged violations of its Ukraine- and Russia-related sanctions. Although that figure represents a much lower share of OFAC’s cases than during the prior year, a lower enforcement rate does not necessarily indicate that OFAC deprioritized Russia-related sanctions. Rather, given the volume and complexity of new restrictions on Russia announced since February 2022—and the amount of time that is often required for OFAC to conduct a fulsome investigation—it is highly likely that further Russia-related enforcement actions could be announced in coming months.

During January 2025, OFAC announced two further settlements resulting in civil monetary penalties, offering an early indication that OFAC is likely to continue aggressively enforcing U.S. sanctions prohibitions throughout the coming year.

2. Statute of Limitations and Supreme Court Cases

Although the Executive branch is responsible for enforcing U.S. sanctions, key developments out of the U.S. Congress and the Supreme Court in 2024, including an expanded statute of limitations for sanctions violations and a growing body of case law limiting judicial deference to administrative agencies, could further reshape both OFAC’s enforcement of violations and its designation of parties to sanctions lists going forward.

On April 24, 2024, President Biden signed into law the 21st Century Peace Through Strength Act, which extends the longstanding statute of limitations for civil and criminal violations of U.S. sanctions from five to ten years. That provision, which Congress quietly inserted into a foreign aid package, appears likely to increase the size of OFAC civil monetary penalties going forward by enabling the agency to reach a broader universe of violative transactions. Notably, OFAC in July 2024 published guidance affirming that the law did not revive civil or criminal sanctions violations that were time barred on the date that the new statute of limitations was enacted into law (i.e., April 24, 2024). As such, absent extenuating circumstances (such as a prior tolling agreement with OFAC), sanctions violations that occurred on or before April 24, 2019 are generally time barred and the new statute of limitations is, as a practical matter, being phased in over the next five years.

Nevertheless, the new ten-year statute of limitations quickly shifted the landscape for compliance-minded companies. Starting on March 12, 2025, parties that engage in transactions that implicate OFAC’s prohibitions will be required to retain relevant records for a period of ten years. The new statute of limitations also alters expectations concerning an appropriate “lookback” period for sanctions-related investigations, mergers and acquisitions due diligence, and representations and warranties in transactional agreements. In light of the potential for increased civil monetary penalties that sweep in twice as much conduct, the expanded statute of limitations could also affect parties’ calculus regarding whether, and under what circumstances, to voluntarily self-disclose to OFAC apparent violations of the agency’s regulations.

Meanwhile, two U.S. Supreme Court decisions announced in June 2024—Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo and Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) v. Jarkesy—threaten to complicate OFAC’s longstanding practices by potentially forcing the agency to litigate more frequently and with a lower degree of judicial deference.

As described more fully in a pair of prior client alerts, the Court in Loper Bright overruled Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council under which U.S. courts were formerly required to defer to agencies’ reasonable interpretation of ambiguous statutory terms. In place of Chevron, courts now must independently interpret statutes and are no longer obligated to defer to agencies, though they may afford agencies’ views a measure of “respect” to the extent those views are persuasive. In a separate opinion handed down that same week, the Court in Jarkesy held that the U.S. Constitution requires the SEC to sue in federal court, not an in-house administrative court, when seeking civil monetary penalties on a ground such as fraud that resembles a traditional action at common law.

As lower courts continue to wrestle with the implications of Loper Bright and Jarkesy, those two cases taken together have the potential to unsettle U.S. sanctions and export controls by encouraging prospective litigants to challenge agency action, channeling more such disputes into U.S. federal court, and resetting the balance of power between challengers and federal agencies such as OFAC and BIS. Accordingly, following a sustained two-decade rise in the use of sanctions and export controls as primary instruments of U.S. foreign policy, OFAC and BIS could soon be forced to weigh whether, in the face of potential legal challenges, they are prepared to continue pushing the limits of their authorities by levying substantial monetary penalties out of court.

U.S. export controls during 2024 continued their rise as indispensable and central tools to further U.S. national security and foreign policy objectives. A key focus of U.S. efforts involved developing new ways to restrict access to certain advanced technologies by perceived geopolitical competitors like China, while allowing for the continued exchange of these technologies among countries that adopt restrictions that parallel U.S. controls.

Rules issued by the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security have always been technical and fact-dependent; indeed, the rules have often required significant scientific knowledge to understand and implement them appropriately. While BIS rules have steadily become more complex, the regulations announced in 2024 accelerated this trend, underlining the sophisticated nature of export controls while emphasizing the need for exporters to have a highly nuanced and technically informed understanding of exactly what they are, directly or indirectly, exporting, reexporting, or transferring, and to whom. Developments in 2024 also highlighted the increasing risks for violations of these rules, with the U.S. Department of Justice (“DOJ”) and BIS both articulating new rules and expectations in order to avoid serious penalties.

Moreover, for the first time, the necessity of understanding these rules has been expanded from exporters themselves to financial intermediaries such as banks. As discussed below, BIS published an unprecedented set of expectations for financial institutions regarding their obligations to ensure compliance with export controls. This was a meaningful departure from past practice—which had placed the onus and risk for compliance chiefly on exporters. Financial institutions have started to develop protocols in this regard, but industry “best practices” remain a work in progress.

Technology is developing so rapidly that export control regulations are unable to keep pace. As such, we fully expect new regulations to be frequently issued, further refining and likely expanding areas of control.

Throughout 2024, BIS continued to focus on tightening controls on the People’s Republic of China and other countries posing diversion risks with respect to semiconductor manufacturing equipment (“SME”), advanced computing items, and quantum computing technology. These efforts led to a flurry of new rulemaking activity over the past year and created many new compliance obligations across industries. While the Trump administration’s export control priorities remain opaque, the compliance complexities associated with these efforts are unlikely to abate.

1. Advanced Computing Items, Semiconductor Manufacturing Equipment, and Supercomputers

Senior U.S. officials, including then-National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan, often described controlling semiconductors as among the Biden administration’s top foreign policy priorities and announced their intention to prevent China from acquiring the most sophisticated chips to slow Beijing’s military modernization. Consistent with that approach, BIS in April 2024 released an interim final rule imposing additional restrictions on SME, advanced computing items, and items supporting supercomputing end uses exported to the PRC and certain “Country Group D” destinations. This new rule also provided clarity to previous semiconductor and supercomputing-related rules issued in October 2022 and October 2023, which we describe in more detail in two prior client alerts.

Interim final rules relating to national security generally become effective immediately on the date that they are released for public inspection in the U.S. Federal Register. The public is invited to submit comments even while implementing the new rule, and these comments will be considered by the agency in drafting a final rule that will supersede the interim final rule once released. In recent years, both the U.S. Department of Commerce and the U.S. Department of the Treasury have used the rulemaking process to engage with various stakeholders in crafting rules on a variety of topics, often due to the breadth of proposed rules, even though such procedural steps are not required for most rules implicating national security concerns.

BIS’s April 2024 interim final rule amends the U.S. Export Administration Regulations (“EAR”)—which are the principal U.S. regulations governing exports of goods, software, and technology that have both military and civilian uses (commonly known as “dual-use” items)—in several notable respects, including:

- The bifurcation of License Exception Notified Advanced Computing (“NAC”) into two new license exceptions.

- A license exception authorizes otherwise licensable exports to specified end users, end uses, or destinations. In general, license exceptions are open to any non-restricted party, and they can be used without seeking specific approval from the U.S. Government, provided that any applicability and recordkeeping requirements are met.

- In this case, License Exception NAC was split into:

- A revised License Exception NAC authorizing exports and reexports of specified items to (1) Country Group D:5 destinations—which includes destinations subject to a U.S. arms embargo (i.e., Afghanistan, Belarus, Burma/Myanmar, Cambodia, Central African Republic, China (including Hong Kong), Cuba, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Eritrea, Haiti, Iran, Iraq, Lebanon, Libya, Nicaragua, North Korea, Russia, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Venezuela, and Zimbabwe)—plus Macau, and (2) entities headquartered in, or with an ultimate parent headquartered in, a Country Group D:5 destination or Macau, subject to a pre-export notification requirement and revised procedures. The rule also clarifies that notification requirements for covered integrated circuits apply to computers and other products incorporating such items.

- A new License Exception Advanced Computing Authorization (“ACA”) authorizing (1) exports, reexports, and transfers (in-country) of specified items worldwide (except to or within Country Group D:5 destinations, Macau, or an entity headquartered in, or whose ultimate parent is headquartered in, a Country Group D:5 destination or Macau, wherever located), and (2) transfers (in-country) within a Country Group D:5 destination or Macau. Exports, reexports, and transfers under License Exception ACA are not subject to the BIS notification requirement, partly in an attempt to minimize the compliance burden on industry.

- Clarification that all exports, reexports, or transfers made pursuant to License Exceptions NAC or ACA require a written purchase order unless specifically exempted.

- Clarification that License Exceptions NAC and ACA are in addition to, not in lieu of, the requirements of License Exception Encryption Commodities, Software, and Technology (“ENC”) and that License Exceptions NAC and ACA cannot be used if additional end-user or end-use restrictions (under 15 C.F.R. Part 744) or embargo restrictions (under 15 C.F.R. Part 746) apply.

- Revisions to BIS’s license review policies specific to covered items, destinations, and end users.

- Due to a previous inadvertent omission, addition of extreme ultraviolet lithography masks to controls targeting the activities of U.S. persons.

- Revision of end-user controls to address support for indigenous “development” and “production” of front-end integrated circuit “production” equipment in Macau and destinations in Country Group D:5 countries, as well as confirmation that parts and components exported for ultimate incorporation into indigenous SME in the PRC also require a BIS license for the initial export.

- Revisions to several Export Control Classification Numbers (“ECCNs”) to correct inadvertent errors, provide clarifications, and to control new items such as monolithic microwave integrated circuit amplifiers, missile-related items, pulse discharge capacitors, and superconducting solenoidal electromagnets, among others.

Collectively, these changes represent significant alterations to the earlier October 2022 and October 2023 controls and underscore the need to remain vigilant to frequent changes in the controls applicable to SME, advanced computing items, and quantum computing technology.

2. Quantum Computing

In September 2024, BIS released an interim final rule imposing additional controls, in conjunction with partner countries, on quantum computing (an emerging field within computer science that uses insights from physics to solve certain problems far faster than traditional computers) and other advanced technologies. This was a clear example of President Biden’s preference for multilateral actions (discussed further below), and also recognized that without joint action the effectiveness of any export restriction will be far reduced. Specifically, the new rule made the following key changes to the EAR:

- Revision of several existing ECCNs and identification of a new subset of “900” series ECCNs (e.g., ECCN 3A901), signifying controls harmonized with the implemented export controls of partner countries. Compared to items subject to multilateral regimes controls (e.g., the Wassenaar Arrangement), these “900” series items have worldwide license requirements and more limited license exception availability. Such items include, among other things, certain additive manufacturing equipment designed to produce metal or metal alloy components, technology for the development or production of coating systems, complimentary metal-oxide semiconductor circuits, parametric signal amplifiers, cryogenic cooling systems and components, gate all-around field-effect transistor (“GAAFET”) technology, scanning electronic microscopes, cryogenic wafer probing equipment, various materials used to develop quantum items, software designed to extract Graphic Design System II or equivalent standard layout data, and quantum computers, as well as certain related equipment, software, and technology for such items.

- Imposition of deemed export and deemed reexport license requirements for certain quantum, integrated circuit, additive manufacturing, and aerospace items, a significant departure from similar controls previously imposed on certain SME and advanced computing items. However, BIS continues to include deemed export and deemed reexport license exclusions with respect to ECCNs 3D001, 3D002, and 3E001 for anisotropic dry plasma etch equipment and isotropic dry etch equipment, and there is a limited exclusion for certain software or technology released to persons whose most recent citizenship or permanent residency is not a country in Country Group D:1 or D:5. Deemed exports are exports that the U.S. Government “deems” to occur between the United States and a foreign person’s home country when technology is shared with a foreign person physically located in the United States. Deemed reexports are exports that occur when technology is shared with a foreign person who has a nationality other than that of the foreign country where the release or transfer takes place. The list of software and technology eligible for this limited exclusion was amended in December 2024.

- In light of personnel shortages in critical quantum-related fields, foreign person employees and contractors that already have access to covered software and technology as of September 6, 2024—particularly those in Country Group A:5 and A:6 destinations—are “grandfathered” in to allow continued access to this information. These shortages are so severe that even foreign persons who are existing employees or contractors and whose most recent country of citizenship or permanent residency is in Country Group D:1 or D:5 may continue to access sensitive GAAFET technology under the general license in the EAR’s General Order No. 6. However, this is only the case if their employer conducts annual reporting. In some cases, personnel with experience in other kinds of quantum technology may even be eligible for that General License if they are newly hired.

- Addition of License Exception Implemented Export Control (“IEC”) to authorize exports and reexports to specified destinations that have implemented similar controls to the United States. Such destinations and eligible items are identified on a list published on BIS’s website, and eligible ECCNs will also state “IEC: Yes” in the ECCN’s list-based license exception paragraph.

3. Validated End User Program

In September 2024, BIS announced the expansion of its Validated End User (“VEU”) program. The VEU program authorizes exports of covered items to pre-vetted end users in certain countries without a separate license required for each export, thereby expediting the export process for identified VEUs. Under the resulting October 2024 final rule, existing VEU authorizations remain available, but data centers in most countries (excluding Country Group D:5 countries) can now apply to be validated end users for exports of specified SME and advanced computing items. The new Data Center VEU program was created to ease the export and reexport burden associated with certain items controlled on BIS’s Commerce Control List (“CCL”)—including certain advanced computing items, but excluding “600” series items and items controlled for missile technology or crime control reasons—to pre-approved, trusted end users. As outlined in the final rule describing these changes, unlike pre-existing General VEU authorizations, in-country transfers among Data Center VEUs of items exported under a Data Center VEU authorization are not permitted.

Requests for Data Center VEU authorization must be submitted via an advisory opinion request to BIS, and such a request must disclose a significant amount of information, as described in 15 C.F.R. Part 748, Supplement No. 8, such as: the proposed VEU candidate’s ownership structure; the list of items for intended export; intended end users; recordkeeping practices; physical and logical (i.e., data) security requirements; current and potential customers; an overview of the data center’s information security plan; an explanation of the network infrastructure and architecture and service providers; an overview of the supply chain risk management plan, export control training program, and compliance program procedures; as well as a legally binding agreement to permit U.S. Government officials to conduct on-site reviews.

Upon review of an application, the End-User Review Committee (“ERC”)—an interagency panel consisting of representatives of the U.S. Departments of Commerce, State, Defense, Energy and, where appropriate, the Treasury—will consider a range of national security factors and may impose conditions upon granting the authorization, such as restricting access to the facilities and limiting the computing power of a given facility. End users that meet Data Center VEU authorization requirements are listed in 15 C.F.R. Part 748, Supplement No. 7, along with the eligible destinations and items. Even if a VEU is approved, however, exporters must obtain certifications from the VEU prior to export, provide the VEU with a written notification of the shipment containing specific details as outlined in 15 C.F.R. § 748.15(g), file semi-annual reports with BIS, and retain all relevant records for a period of at least five years. Likely due to the extensive pre-authorization requirements and substantial ongoing compliance obligations, no Data Center VEU authorization has been publicly granted to date. BIS further amended its Data Center VEU authorization, imposing additional security requirements among other changes, in a January 2025 interim final rule on AI discussed further below.

4. Advanced Semiconductors for Military Applications

In December 2024, BIS unveiled a new set of expansive regulations that the agency described as having been “designed to further impair the [PRC’s] capability to produce advanced-node semiconductors that can be used in the next generation of advanced weapon systems and in artificial intelligence . . . and advanced computing, which have significant military applications.” The accompanying interim final rule imposed broad new controls on SME and advanced computing items, implemented new Foreign-Direct Product (“FDP”) rules—which extend U.S. jurisdiction to foreign-made items that are the “direct product” of controlled U.S.-origin technology or software, or of a manufacturing facility or equipment derived from such controlled U.S. technology or software—and further revised the EAR to clarify the scope of related controls as follows:

- New and revised ECCNs control certain SME equipment (including certain etch, deposition, lithography, ion implantation, annealing, metrology and inspection, and cleaning tools), software tools for developing or producing advanced-node integrated circuits, high-bandwidth memory stacks, electronic computer-aided design software and technology, and technology computer-aided design software and technology.

- Two new FDP rules extend the scope of the EAR to include certain foreign-manufactured items that (1) are the direct product of, (2) are the product of a complete plant or major component of a plant that is itself the direct product of, or (3) contain a product of a complete plant or major component of a plant that is a direct product of, specified U.S.-origin software or technology. This third prong, capturing items “containing” a component that is a foreign direct product of U.S. software or technology, is a novel expansion of the FDP rule that as a practical matter renders such components ineligible for de minimis treatment when assembled into items produced abroad. From a policy perspective, these new rules are aimed at combatting efforts by the PRC to obtain foreign-manufactured SME and advanced computing items as follows:

- The new SME FDP rule applies to certain foreign-manufactured SME and related items whenever an exporter has “knowledge,” as defined under the EAR to cover actual knowledge and an awareness of a high probability, which can be inferred from acts constituting willful blindness, that a covered item is destined to a Country Group D:5 destination or Macau.

- Similarly, the new Footnote 5 FDP rule applies to specified foreign-manufactured items used to produce advanced-node integrated circuits whenever an exporter has “knowledge” that the item will be (1) incorporated into any part, component, or equipment produced, purchased, or ordered by any Entity List entity with a Footnote 5 designation or (2) when any such designated entity will be a party to a transaction involving the commodity (e.g., as a purchaser, intermediate consignee, ultimate consignee, or end user). BIS notes that the new Footnote 5 designation is calculated to help industry identify foreign parties involved in supporting the PRC’s efforts to produce advanced-node semiconductors, including for military end-uses. A companion final rule added 140 new entities to the Entity List and modified 14 existing entries, resulting in a total of 16 entities with the new Footnote 5 designation.

- Adds corresponding licensing requirements to Parts 742 and 744 of the EAR to restrict the export, reexport, and transfer of items within the scope of the new FDP rules discussed above and the new and revised ECCNs discussed above, though certain exceptions are available, including for countries implementing equivalent controls listed in 15 C.F.R. Part 742, Supplement No. 4.

- Revises the De Minimis rule—which allows foreign-made items that incorporate less than a certain de minimis amount of controlled U.S.-origin content to be exempt from most U.S. export restrictions—to specify there is no de minimis level for certain SME and advanced computing items that contain a U.S.-origin integrated circuit whenever such items are destined for a Country Group D:5 destination or Macau or to a Footnote 5 Entity List entity. These new provisions ensure that foreign-produced SME containing U.S.-origin integrated circuits (or other components) are controlled to the same extent as foreign-produced SME containing items controlled by the SME FDP rule and the Footnote 5 FDP rule.

- New License Exception Restricted Fabrication Facility (“RFF”) permits the export of certain legacy SME and related items to certain fabrication facilities subject to end-user requirements, provided that these facilities are not engaged in the production of advanced node integrated circuits. Eligibility for License Exception RFF is tied to specific entities on the Entity List that contain a reference to 15 C.F.R. § 740.26, and its use is subject to various notification and reporting obligations as stipulated in that section.

- New License Exception High-Bandwidth Memory (“HBM”) authorizes the export of certain HBM commodities controlled under the new ECCN 3A090.c under a narrow set of circumstances, provided that specified recordkeeping and notification requirements are met.

- Eight new red flags were added to BIS’s “Know Your Customer Guidance” in 15 C.F.R. Part 732, Supplement No. 3 concerning due diligence efforts that must be undertaken by exporters in various scenarios before SME and advanced computing items subject to the EAR may be exported. In particular, Red Flag 26 and the accompanying text in the interim final rule make clear the sweeping implications of the new FDP rules. In Red Flag 26, BIS notes that, due to the prevalence of U.S.-origin tools in the global production of integrated circuits, exporters should operate under the presumption that any integrated circuit is likely produced from controlled U.S. software or technology. Thus, if a foreign-produced item is described in the relevant Category 3B ECCN and contains at least one integrated circuit, there is a presumption that the product meets the product scope of the applicable FDP rule. Accordingly, an exporter must resolve this red flag before proceeding with the transaction.

- Clarified end-use controls related to the development and production of advanced-node integrated circuits, the definition of “advanced-node integrated circuit,” certain general prohibitions, and a temporary general license authorizing the export of certain less-sensitive SME and advanced computing items to account for the new controls.

- Clarified that software license keys (e.g., software used to activate or renew licenses to access certain software or hardware) are classified and controlled under the same ECCNs as the software or hardware to which they provide access (or the corresponding software ECCN, in the case of access to hardware). For example, if a software license key provides access to ECCN 5A992 hardware, the key itself is classified under ECCN 5D992.

5. Mature-Node Semiconductors

In December 2024, BIS released its long-awaited Public Report on the Use of Mature-Node Semiconductors, concluding a process that began in January 2024. The report aimed to provide an overview of the use of mature-node semiconductors in supply chains that support U.S. critical infrastructure. The report based its findings on data collected from a sample of industry participants and highlighted the lack of visibility into semiconductor supply chains and the pervasive use of semiconductors manufactured by foundries located in the PRC—even though semiconductors represent a limited share of the total number of chips used in specific products. The report also highlighted how the expansion of production capacity in the PRC is beginning to impact the competitive position of U.S. chips in the global market.

6. Artificial Intelligence

The rapid rise and proliferation of artificial intelligence led the U.S. Government to implement sweeping export control regulations on AI technologies. The rules were so sweeping that they gave rise to unprecedented complaints from both U.S. hardware and software providers, as well as core U.S. allies, that the regulations were so draconian as to limit their ability to actually work on AI in manner that would be fast enough to compete with the technology emerging from China.

With respect to the regulations, in a break from the hardware-based controls on the semiconductors and semiconductor manufacturing equipment necessary to produce an AI application or large-language model, BIS in September 2024 proposed its first rule directly regulating AI itself.

The basis for this rule was unusual for BIS: Executive Order 14110, which was issued by President Biden in October 2023 to implement the Defense Production Act of 1950 (a Korean War-era statute that authorizes the President to ensure the supply of materials and services for the national defense of the United States). Consequently, the proposed rule focused on gathering information necessary to protect U.S.-origin AI products or to ramp up defense industry production of such products, rather than controlling the export of any commodities, hardware, or software. The rule would require companies, individuals, or other organizations or entities that acquire, develop, or possess a potential dual-use foundation AI or large-scale computing cluster to file a quarterly report with BIS regarding any such acquisition, development, or possession, including the existence and location of clusters and the amount of total computing power available in each cluster. This reporting requirement includes information regarding the characteristics, safety (e.g., self-replication or propagation constraints, constraints on use to influence real or virtual events, constraints on ability to use the model to develop, produce, or use weapons of mass destruction), reliability, training, and cybersecurity protections of the models and regarding ownership and protection of model weights.

Notably, the rule defines a “dual-use foundation model” as a model that is “trained on broad data; generally uses self-supervision; contains at least tens of billions of parameters; is applicable across a wide range of contexts; and that exhibits, or could be easily modified to exhibit, high levels of performance at tasks that pose a serious risk to security, national economic security, national public health or safety, or any combination of those matters.” This framing significantly limits the scope of covered models.

BIS followed up on January 13, 2025 by issuing an interim final rule on AI diffusion, which aims to maintain U.S. technological leadership over AI by reducing diversion of advanced AI models to Country Group D:5 destinations (which, as noted above, include China and Hong Kong) and Macau, and to support development of these models in validated entities in a small set of partner countries, where they will be stored under stringent security conditions.

Notably, this rule requires a license to export, reexport, or transfer (in-country) advanced computing integrated circuits or the model weights of the most advanced AI models to any end user in any destination. In particular, it controls the export of model weights for advanced, closed-weight dual-use AI models trained on more than 1026 computational operations in a new ECCN 4E091, as well as the export of large clusters of advanced computing integrated circuits (which can support such models) in modified ECCNs 3A090.a and .z and 4A090.a and .z. (The model weights for open-weight models do not presently require a license, and the rule also does not impose new controls on application programming interfaces to access AI platforms.) BIS also provided guidance to exporters who need assistance self-classifying their models.

The rule focuses on model weights, rather than the models themselves, because model weights are more challenging to develop, require extensive model training, and are easy to copy and steal. Model weights with fewer than 1026 computational operations are already widely published and therefore hard to control. There is, however, a recognition that the pace of technological development may render these various weights quickly out-of-date.

The U.S. Government will review applications for controlled exports, reexports, and transfers (in-country) based on the sensitivity of the destination, the quantity of compute power or performance of the AI model, and the security requirements agreed to by the recipient. The rule establishes a licensing policy of presumption of denial for both model weights and certain large quantities of advanced computing integrated circuits needed to train advanced AI models. Moreover, foreign-produced model weights of similarly advanced closed-weight models may also be controlled by this rule, through a new foreign direct product rule in 15 C.F.R. § 734.9(l). BIS expects such models to be subject to the rule, as it has “found that many foreign entities that are training advanced AI models or intend to train such models are using advanced computing [integrated circuits] and related items that were directly produced with U.S. technology.”

Despite the rule’s stringent licensing policy, BIS permits certain exports to proceed by providing:

- License Exception Artificial Intelligence Authorization (“AIA”) authorizing the export, reexport, or transfer of both advanced integrated circuits and model weights to end users located anywhere other than Country Group D:5 or Macau if they are employed by an entity headquartered in destinations where (1) the government has implemented measures with a view to preventing diversion of advanced AI technologies, and (2) there is an ecosystem that will enable and encourage firms to use advanced AI models for activities that may have significant economic benefits. BIS and partner agencies have listed approved countries in paragraph (a) to 15 C.F.R. Part 740, Supplement No. 5. Notably, that list does not include all members of the Global Export Control Coalition, which has partnered together to implement “substantially similar” controls on Russia, nor does it include all countries eligible for License Exception IEC, described above. Instead, it presently covers only Australia, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Republic of Korea, Spain, Sweden, Taiwan, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Even within these countries, exporters and reexporters may not take advantage of this exception unless they ensure that the end user has instituted specific security measures that will reduce the risk of diversion, specified in 15 C.F.R. Part 748, Supplement No. 10, and exporters of advanced integrated circuits must first obtain a compliance certification from the ultimate consignee.

- License Exception Advanced Compute Manufacturing (“ACM”) authorizing the export, reexport, or transfer of items controlled by the rule to private sector end users located outside of and not headquartered in (or with an ultimate parent company headquartered in) Country Group D:5 or Macau, for the development, production, or storage of the same kinds of items (when ultimately not destined to Country Group D:5 or Macau)—but not for any other activity, including training an AI model. Parties who use this license exception are expected to keep up-to-date inventory and distribution records.

- License Exception Low Processing Performance (“LPP”) authorizing the export and reexport of certain advanced integrated circuits with low computational power—up to 26,900,000 Total Processing Performance (“TPP”) of advanced computing integrated circuits per-calendar year, in aggregate across all exporters for that year, to any individual ultimate consignee located outside of and not headquartered in (or with an ultimate parent company headquartered in) Country Group D:5 or Macau. Because this license exception covers the total amount of TPP an end user can receive in a year from all exporters and reexports, before using License Exception LPP, the exporter or reexporter must obtain (and ultimately provide to BIS) a certification from the ultimate consignee that the ultimate consignee has not received an aggregate of 26,900,000 TPP during the relevant calendar year and that the requested TPP for that specific transaction will not result in the ultimate consignee exceeding the TPP limit.

- An expanded License Exception ACA, which now authorizes the export and reexport of covered items to any destination worldwide other than Country Group D:5 or Macau (or to related entities), and not just to destinations in Country Group D:1 or D:4.

- A clarification of the questions BIS uses as its review criteria for License Exception NAC, which allows shipment of some advanced integrated circuits to Macau and Country Group D:5 with advanced notice to the U.S. government.