UK Supreme Court Confirms the Limits of the SFO’s Section 2(3) Power

Client Alert | February 8, 2021

On February 5, 2021, in a unanimous decision, the UK Supreme Court ruled that the SFO’s so-called “Section 2” power, found in section 2(3) of the Criminal Justice Act 1987 (“CJA”), cannot be used to compel a foreign company that has no UK registered office or fixed place of business and which has never carried on business in the UK, to produce documents it holds outside the UK. In so ruling, the Supreme Court overruled a 2018 Divisional Court decision that held that the SFO could use its power in this way, provided that there was a “sufficient connection” between the foreign company and the UK.

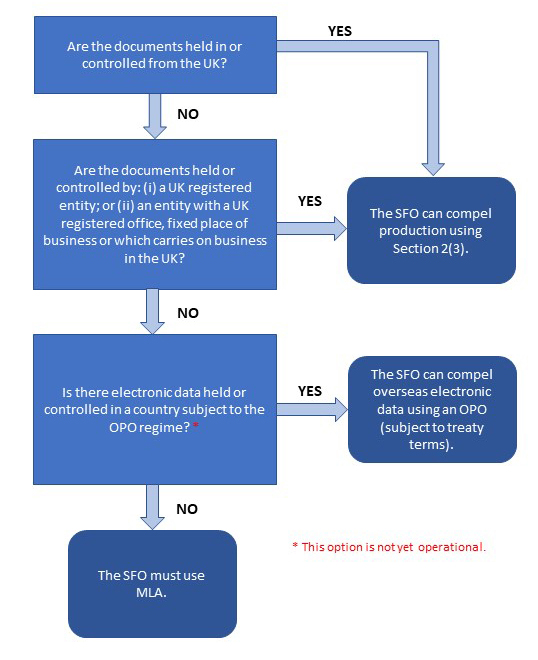

In this alert we provide an overview of the Supreme Court’s decision and offer our observations on the implications of the judgment for the SFO and foreign companies under investigation. We conclude with an illustrative summary of the different methods available to the SFO to obtain documents following the Supreme Court’s decision.

The decision will come as a setback for the SFO, which will now have to rely on the often cumbersome and slow Mutual Legal Assistance (“MLA”) route to obtain documents in these circumstances. The loss is compounded as the Supreme Court decision comes shortly after the UK lost access to certain investigatory powers it enjoyed by virtue of the UK’s (now prior) Membership of the European Union (“EU”), such as the European Investigation Order (“EIO”), which enabled the SFO to quickly obtain evidence, including documents, located in the EU.

Waiting to become operational is the agreement signed between the UK and U.S. in October 2019 to implement the Crime (Overseas Production Orders) Act 2019. Once in effect, the SFO, as well as other UK investigations agencies, including the Financial Conduct Authority, will be able to obtain certain “electronic data” located or controlled from the U.S. via an Overseas Production Order (“OPO”). OPOs will be issued by an English court, and the recipient must provide the data, ordinarily within seven days, to the agency named in the OPO. Although OPOs will enable authorities to obtain evidence faster, they do not apply to hard copy and certain other material, such that MLA requests will remain a necessary route in many instances. Whilst it is the intention of the UK Government to enter into agreements with other countries and blocs such as the EU, the UK/U.S. agreement is the only such agreement currently in place.

The Supreme Court decision will obviously be disappointing for the SFO. However, it will support an argument that the Government needs to consider the scope of the SFO’s powers, to ensure it has the tools necessary to investigate sophisticated, organised criminal wrongdoing in an increasingly globalised world.

Section 2 Notices

Section 2(3) of the CJA provides that “The Director [of the SFO] may by notice in writing require the person under investigation or any other person to produce … any specified documents which appear to the Director [of the SFO] to relate to any matter relevant to the investigation or any documents of a specified description which appear to him so to relate”.

It is a criminal offence to fail to comply with section 2(3) of the CJA without a “reasonable excuse”.

Section 2 notices are attractive to the SFO because the SFO alone may determine whether to compel a recipient to produce documents, and may serve the notice directly upon the recipient and enforce non-compliance. It requires no court or other third-party intervention, thereby providing a rapid, effective and largely self-regulated method of compelling the production of documents.

Background

KBR, Inc. is a U.S. incorporated engineering and construction company and the parent company of the KBR Group. In 2017, KBR, Inc.’s UK subsidiary, Kellogg Brown & Root Ltd (“KBR UK”), was under investigation by the SFO for suspected bribery. During this investigation, a representative of KBR, Inc. attended a meeting with the SFO in the UK to discuss its investigation into KBR UK. During that meeting, the SFO issued a notice to KBR, Inc. under section 2(3) of the CJA compelling the production of documents held outside of the UK (the “July Section 2 Notice”). KBR, Inc. did not have a fixed place of business in the UK and had never carried on business in the UK.

KBR, Inc. sought permission to apply for judicial review of the decision and to quash the July Section 2 Notice in the Divisional Court, on three grounds:

- The July Section 2 Notice was ultra vires the CJA as it requested material held outside of the UK from a company incorporated outside of the UK;

- The Director of the SFO made an error of law in issuing the July Section 2 Notice instead of using its power to seek MLA from the U.S. authorities under the UK’s 1994 bilateral U.S. MLA Treaty; and

- The July Section 2 Notice was not properly served on KBR, Inc. under the CJA.

In September 2018, the Divisional Court held that the SFO could require a foreign company to produce documents held overseas pursuant to section 2(3) of the CJA where there is a “sufficient connection between the company and the jurisdiction”. The Court held that there was a sufficient connection between KBR, Inc. and the UK in this case, as payments made by KBR UK required the express approval of KBR, Inc., were paid by KBR, Inc. through its U.S.-based treasury function, and for a period of time KBR, Inc.’s compliance function was required to approve the payments. In addition, an officer of KBR, Inc. was based in the KBR Group’s UK office. The fact that KBR, Inc. was the parent company of KBR UK was not sufficient by itself to establish a “sufficient connection”.

The Supreme Court Case

KBR, Inc. was granted leave to appeal and made the following arguments in the Supreme Court:

- Presumption against Extra-Territorial Effect and Principle of International Comity: there is a presumption under English law that a statute has no extra-territorial effect, as this would constitute a breach of international comity – namely, the principle of recognising, upholding and respecting other jurisdictions’ legislative and judicial acts.

- Wording of the CJA: the terms of the CJA do not suggest a Parliamentary intention to confer extraterritorial powers upon the SFO.

- Role of Parliament vs the Court and the “Sufficient Connection” test: the decision regarding the extraterritorial application of the CJA is a matter for Parliament rather than the Court. As such, the decision to introduce a “sufficient connection” test would be a question to be answered by legislation, rather than one of judicial interpretation.

Presumption against Extra-Territorial Effect and Principle of International Comity

The Supreme Court held that the “starting point” for the consideration of the scope of section 2(3) is the presumption in English law that “legislation is generally not intended to have extra-territorial effect”. This presumption, according to the Supreme Court, is rooted in both the requirements of international law and the concept of comity, which is founded on mutual respect between states.

The Supreme Court emphasised that whilst the principle of comity was not a “rule of international law” as such, the “lack of precisely defined rules in international law as to the limits of legislative jurisdiction makes resort to the principle of comity as a basis of the presumption applied by courts in this jurisdiction all the more important”.

Lord Lloyd-Jones, writing for the Supreme Court, acknowledged the “legitimate interest of States in legislating in respect of the conduct of their nationals abroad”, however, he held that this case did not concern the conduct of a UK national or UK registered company abroad. If the addressee of the July Section 2 Notice had been a UK registered company, section 2(3) would have authorised the service of a notice to produce documents held abroad by that company.

Since the addressee of the July Section 2 Notice, KBR, Inc., had never carried on business in the UK or had a registered office or any other presence in the UK, the Supreme Court held that the presumption against extra-territorial effect clearly did apply to this case. The question for the Supreme Court was, therefore, whether Parliament intended section 2(3) to displace the presumption to give the SFO the power to compel a foreign registered company with no registered office or fixed place of business in the UK and which did not conduct business in the UK to produce documents it holds outside the UK.

Wording of the CJA

With respect to the question of whether the presumption against extra-territorial effect had been rebutted by the language of the CJA, the Supreme Court held that the “answer will depend on the wording, purpose and context of the legislation considered in the light of relevant principles of interpretation and principles of international law and comity.”

The Supreme Court noted that “when legislation is intended to have extra-territorial effect Parliament frequently makes express provision to that effect” and, unlike other statutory provisions, section 2(3) “includes no such express provision”. Moreover, the Supreme Court found that the other provisions of the CJA do not provide “any clear indication, either for or against the extra-territorial effect.”

Role of Parliament vs the Court and the “Sufficient Connection” Test

KBR, Inc. submitted that:

- The extraterritorial application of an investigatory power involving criminal sanctions, where the regulatory authority purports to exercise those powers in relation to persons and documents abroad, is a matter more appropriate for the legislature to assess rather than the court – as Parliament would be able to simultaneously address the issue of international comity and the proper conditions / safeguards to be imposed with such a power; and

- The court should resist the suggestion made on behalf of the SFO that the court should imply into section 2(3) of the CJA a “sufficient connection” test, as no such test was incorporated by Parliament into this statutory scheme.

The Supreme Court held that there was no basis for the Divisional Court’s ruling that the SFO could use the power in section 2(3) of the CJA to require foreign companies to produce documents held outside the UK if there was a “sufficient connection” between the company and the UK. Implying a “sufficient connection” test into section 2(3) “would exceed the appropriate bounds of interpretation and usurp the function of Parliament” and would involve illegitimately re-writing the statute.

Implications

The SFO has been using section 2(3) notices to compel the production of documents held outside of the UK for many years. Their use suited not only the SFO but also often recipients who were provided with a seemingly lawful basis to produce often confidential and sensitive documents to the SFO. In its use of the power, the SFO has generally proceeded judiciously, avoiding potential disputes from section 2notice -recipients it perceived as likely to take jurisdictional arguments. It may now be regretting its decision to use the section 2 power against KBR, Inc.; the SFO’s apparent impatience caused it to err in its judgment and use the power against a suspect with every reason to challenge the jurisdiction of the notice.

Although this case could be characterised as something of an “own goal” for the SFO, and is doubtless a setback, the Supreme Court’s decision may provide a basis for the SFO to argue that the Government needs to reconsider the scope of its powers, in order to ensure that it has the tools it needs to operate as a leading criminal enforcement agency. Many of the laws it is expected to enforce (not least the Bribery Act 2010) have extraterritorial reach after all.

In the meantime, the setback caused by this judgment is amplified by the fact that, like other UK prosecuting agencies, it has recently lost access to certain cross-border investigatory powers it enjoyed while the UK was a Member of the EU. In the context of document gathering, the loss of the EIO, that facilitated streamlined obtaining of evidence located in the EU as an alternative to MLA, is the most significant loss.

For the SFO, all is not lost as a result of this decision, however. Since the Divisional Court decision in 2018, the UK passed the Crime (Overseas Production Orders) Act 2019, which entered into force on October 9, 2019. That Act enables officers of specified investigative agencies, including the SFO, to apply to a UK court for an OPO requiring the production within seven days of stored electronic data located or controlled outside the UK, for use in the investigation and prosecution of certain indictable offences. This power can only be exercised where a designated international co-operation arrangement exists between the UK and the country where the electronic data is located or from where it is controlled. To date, the UK has only agreed one such agreement, with the U.S. in October 2019. The agreement is yet to become operational, but when it is, it will provide an alternative to the MLA route, although the scope of the agreement provides for production of a narrow category of documentation. Further, unlike the use of section 2(3) CJA, the SFO will need to make an application to a court and require the UK Central Authority, which coordinates MLA requests, to approve and serve the OPO.

Unless the SFO can convince the Government to extend the scope of its evidence-gathering powers by passing new legislation, and until OPOs become operational, the SFO will have little choice but to rely, in most cases, on the cumbersome and slow MLA route to obtain evidence from foreign registered companies with no registered office or fixed place of business in the UK or which do not carry on business from the UK.

Practical Implications

The following diagram provides a summary of the different ways that the SFO can obtain documentary evidence, both now and when OPOs become operational:

Illustrative Practical Examples:

- The SFO can compel the production of documents held by overseas branch offices of UK registered entities.

- The SFO can compel production of documents held in the cloud by a UK registered entity.

- The SFO cannot compel documents held or controlled by an overseas parent or subsidiary of a UK registered entity.

The following Gibson Dunn lawyers assisted in the preparation of this article: Patrick Doris, Sacha Harber-Kelly, Steve Melrose, Katie Mills and Rebecca Barry.

Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher’s lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding these developments. If you would like to discuss this alert in detail, please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, the authors, or any member of the firm’s UK disputes practice in London:

Patrick Doris (+44 (0) 20 7071 4276, pdoris@gibsondunn.com)

Sacha Harber-Kelly (+44 (0) 20 7071 4205, sharber-kelly@gibsondunn.com)

Steve Melrose (+44 (0) 20 7071 4219, smelrose@gibsondunn.com)

Allan Neil (+44 (0) 20 7071 4296, aneil@gibsondunn.com)

Matthew Nunan (+44 (0) 20 7071 4201, mnunan@gibsondunn.com)

Please also feel free to contact the following leaders and members of the firm’s White Collar Defense and Investigations practice:

Kelly Austin – Hong Kong (+852 2214 3788, kaustin@gibsondunn.com)

Joel M. Cohen – New York (+1 212-351-2664, jcohen@gibsondunn.com)

Nicola T. Hanna – Los Angeles (+1 213-229-7269, nhanna@gibsondunn.com)

Charles J. Stevens – San Francisco (+1 415-393-8391, cstevens@gibsondunn.com)

F. Joseph Warin – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3609, fwarin@gibsondunn.com)